Ariane Plante

Ariane Plante is an artist who works in sound, photography, video, and installation. Having completed her studies in anthropology, she brings an understanding of what is actual field work and good methodology, to her sensitive and complex projects. Understanding more about her process, and experiencing the appreciative results, confirms for me a long-standing conviction, having attended, and taught in art schools: the best thing for artists to do is study something else in detail, that can be brought to bear on one’s practice.

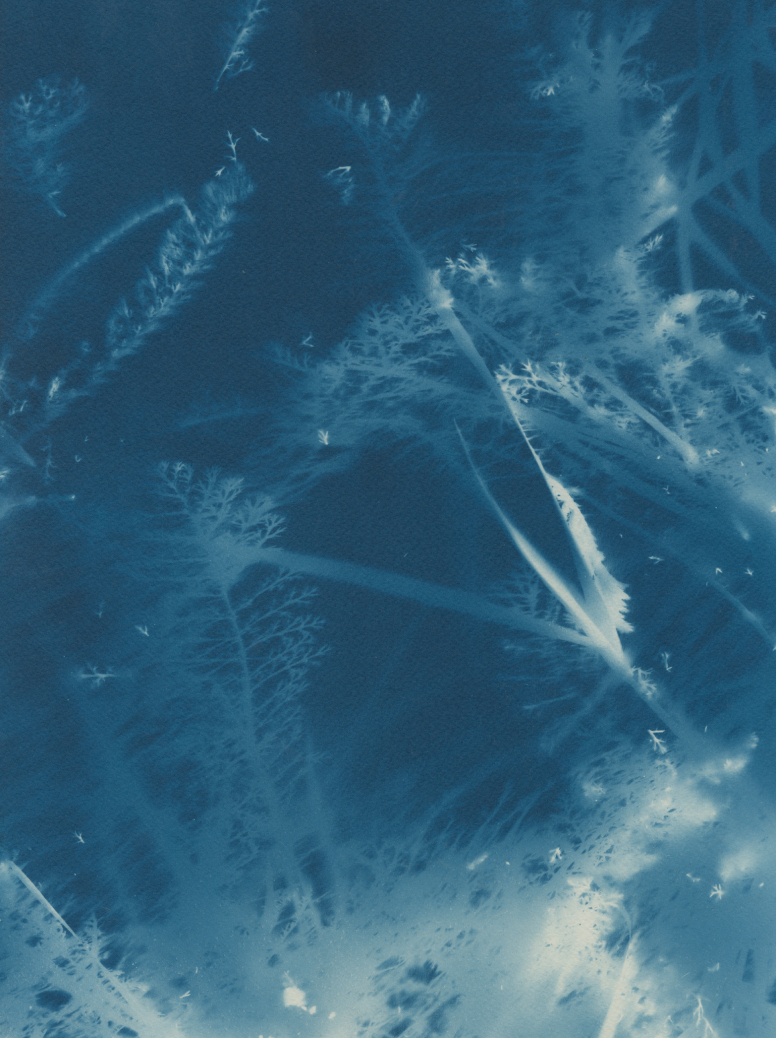

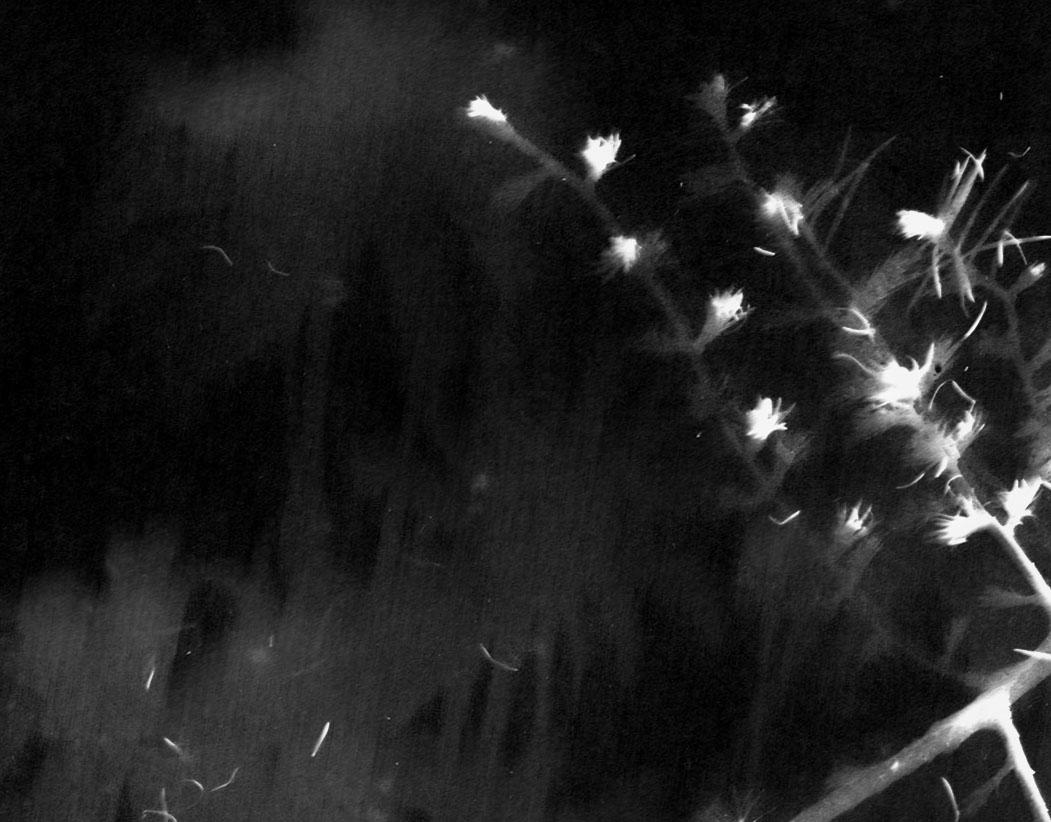

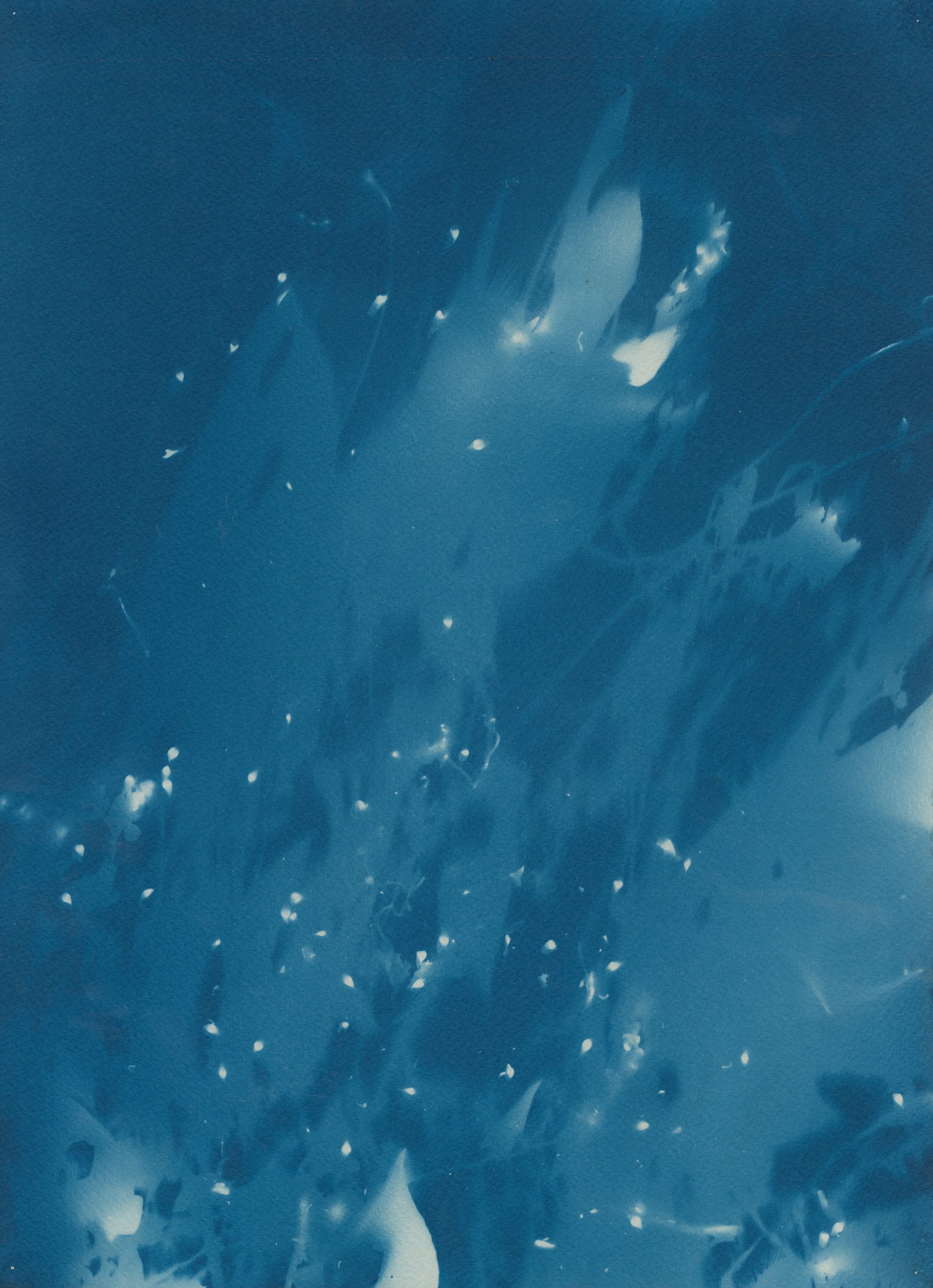

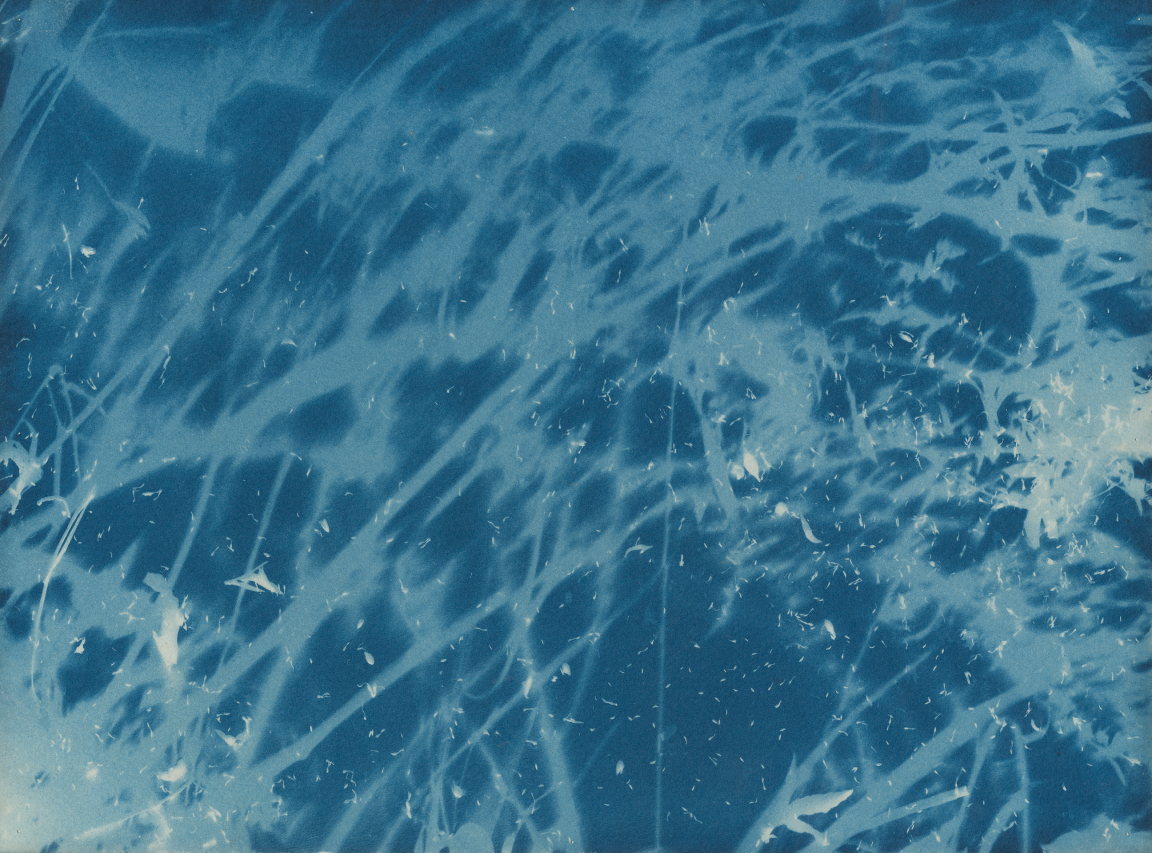

Un herbier de sons (working title), which is the project I focus my attention on here, is a multi-channel sound and visual diptych that combines antiquated photographic processes, audio, and digital technology. I quote from her artist’s statement: “Through the use of cyanotypes and sound samples made and collected in a specific ecosystem, the work recreates an environment while sublimating it. The project aims to crystallize the imprints of selected territories and their bioacoustics, to reflect the fragility of habitats under the pressure of human activity. Both an archive and a soundscape, Un herbier de sons seeks to preserve the memory of the place at a specific moment, by restoring the visual and sonic “musicality” from subjective points of view and hearing, while echoing the transformations that agitate it.”

In recent years, we have seen the cyanotype process crop up in many artists’ work, but few make as satisfying a connection to the material’s origins, as does Ariane’s intelligent use of this humble photographic technique. Discovered in the early 1840s (a few years after the invention of the Daguerreotype and Talbotype – two much more complicated, expensive, and toxic photographic processes), the cyanotype is sometimes referred to as “the Sun and river process”. (The emulsion is activated with UV light, and developed and stabilized into an image with water. It was utilized well into the 20th century as an economical way of making document copies; we still use the word “blueprint” in reference to the process’ Prussian blue colouring.)

Some of the earliest cyanotype photograms were studies of plants, a knowledge which Ariane loops into her work for Un herbier. The images from this series feel fresh, being very surprising in shapes (of shadows cast by objects) and compositions (relationships between biological forms), even though for what I would know (given the unchanging nature of this process), those very images really could have been made a hundred years ago. Either way to my mind, they are simply as beautiful looking today, as I would imagine the first botanical studies made with the process must have looked to a wonder-filled viewer in the 1840s.

Ariane’s images are scanned and fed into a computer program, which, in exhibition, will make combinations and sequences of the cyanotypes appear then fade before our eyes; this second stage of imaging decidedly locates Un herbier within our own time, and prevents the project from falling into a nostalgic exercise for long lost processes. It is the world that is disappearing, not some analogue process from the days of yore that we should be worried about. This seems to be one of the points of Un herbier, and it is made by Ariane’s pertinent way to use her materials: a cyanotype made today necessarily refers to the past, while its translation into the realm of digital projection, precisely and economically finds the language that we speak today, and then changes what we generally like to say with it (high speed, high volume, oversaturation and overstimulation), in order to call our attention to the fact that all the shadows we are seeing in all these different ways, are all very much disappearing everywhere. It’s a beautiful thought, that is only mitigated by the trauma of realizing what it really means.

I must, however, confess that in my imagining of how this work is made, there is something really delightful that I keep coming back to, about someone named Plante, wandering alone into a landscape on sunny afternoons, and tucking pieces of light-sensitized paper into tall windblown grasses, pinning pieces of paper to tree branches and flowers, and then waiting patiently (and keeping track of where all those pieces of paper were left…) while shadows and light describe a fast-vanishing world.

I think that what I respond to so powerfully in all this, is the embodied and empathetic stance Ariane takes toward her subject matter, and the near 1:1 relationship between what is being represented from the world, with how it is represented in her work. Thinking my way through what I understand of her process, has caused me to realize (for the first time?) how irrational and disconnected is so much art, from the actual subject matter that is depicted about the world. It has had a strong enough effect on me, that I now feel bothered, when I realize that what some artists do in their work, and what they are depicting from the world that they take their imagery from, have almost no integral or even sympathetic relationship to one another (even when what one is doing it for, is a laudable cause, and I’m upset to realize that I may be one of them…); the hands do one thing, the body another, the mind absolutely must be focusing on solving a technical question, the eyes are tunnelled into what can fit inside the rectangle of the image. We just take for granted that standing in a field and swinging some apparatus around a bit, will gain results that we can appreciate. Yes, sometimes.

But, perhaps it is with the realization that we cannot keep going on like we have become conditioned, even in artistic pursuits, let alone in our day-to-day lives, that we need to change our relationships to each other, to the world around us, to the way that we are in it. Ariane’s artistic actions, to my mind, narrow the gap between a good cause, and a good methodology, to a breathtakingly symmetrical degree.

Rather than commenting on ecological issues by means of ecologically destructive processes (a contradiction I’ve never fully appreciated the logic of, and that I find lurking beneath so many “environmental” artists work…), Ariane uses very simple means, and highly sensitive and gentle ways to deploy contemporary processes, in order to engage us with complex issues of being in the world. I think of Ariane as a landscape artist; when I make the comparison with other landscape artists, I am really struck by a very pronounced contrast. Ariane doesn’t treat her subject matter as though it is in a “zoo” that you are invited to visit and then leave when you’ve had enough; it doesn’t shrink the world into the size and shape of the frame. When I look at her images, or listen to her audio works, I am left with the feeling that what fell beyond the borders of the piece of paper, or what the microphone doesn’t quite hone in on, is just as important as what eventually did fall within its borders.

I don’t get the impression, either, that her works were made by someone who drove their 4×4 up the side of a hill, set up their camera, took a photo, then drove back down to show us the evidence (of “our” destructive ways). When I engage with her work, I feel as though I follow along a process, to arrive at some kind of communion with things, and with people, that weren’t waiting for us to find them; but now that we have, they will tell us something, and welcome us as we are. Drawings made with addition of light, stories told with addition of sounds; one by one, and taken together, her projects embody a deep empathy and understanding of what it means to live amongst other beings, and amongst other things, and shows a way that we might follow too, if we would simply sensitize ourselves to others, as well.

Artist

Based in Montreal, Ariane Plante is an artist and curator in visual and media arts. Self-taught, she holds a university degree in anthropology and has been working in the arts milieu since 2005. Recipient of grants from the Canada Council for the Arts, the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec and Première Ovation, her work has been presented in Quebec, Canada, France, on online platforms and in digital publications.

She has participated in collective exhibitions and events such as Truck Stop, organized by CLARK and L’Œil de poisson (2017), the exhibition Extension et pratique des idées, initiated by VU and presented at the Musée d’art de Baie-St-Paul as part of Manif d’art 8 and then in Marseille (2017 and 2018), or the Grand Happening of Avatar (2014). She recently produced and published a radio sound creation commissioned by Avatar for the Repères project (2020), and also participated in the virtual exhibition Cadrer la nature (October 1, 2020 to January 8, 2021), presented by the Centre d’exposition de l’Université de Montréal.

Since 2015, she has been working on the creation of sound herbariums, a long-term research project in which she archives natural ecosystems that have been weakened by human activity to account for their transformation in a digital, visual and sound installation.

In the fall of 2020, she began a cycle of work on the figure of silence in the landscape and the creation of intermedia dioramas.

Curator from 2016 to 2018 editions of the Mois Multi, Quebec City’s international festival of multidisciplinary and electronic arts, she now works independently and collaborates with various artists and organizations in the contemporary arts. Since 2018, she has also been developing the digital visual arts exhibition component of the Grand Théâtre de Québec, for which she acts as consultant and curator.

Links