By: Bart Gazzola

Elena Chernyshova | Days of Night / Nights of Day, 2012-2013

December 8, 2022Elena Chernyshova | Days of Night / Nights of Day, 2012-2013

‘I was with my people then, there, where my people, unfortunately, were.’

(Anna Akhmatova, Requiem, 1935 – 1961, writing of her times in the soviet gulag)

When I lived in Saskatoon, an acquaintance who’d spent time in Eastern Europe once commented that that city in winter was like Siberia, but without the cachet of being that place (which exists as much in our imaginations as it does in reality, one might say – as a ‘great part of the imagination of the world is attached to that site’), nor with architecture that was anything but a failed brutalism (this was during a period with the ‘economic boom’ in Saskatoon where a number of heritage buildings were lost and the banal taupe of others rose like mottled angular tumours….)

Elena Chernyshova’s work is aesthetically stunning: not just for the evocative quality of the images, but also for the scenes they present to us, that seem to blend exotica and danger, a chronicle of sites that remind us of the irrelevance of humanity in the face of nature.

But her notes and comments bring the human element back, as this is not just a ‘pretty’ image, but a site of – of course – contested narratives, that looks back to the history of the USSR and some of the ideas of industrialization and ‘progress’ that have human costs.

Chernyshova’s own words are a powerful adjunct to her lens: “Days of Night / Nights of Day is about the daily life of the inhabitants of Norilsk. Norilsk is a mining city, with a population of more than 170,000. It is the northernmost city (100,000+ people) in the world. The average temperature is -10° C and reaches lows of -55° C in the winter. For two months of the year, the city is plunged into polar night when there are zero hours of sunlight.

The entire city, its mines and its metallurgical factories were constructed by prisoners of the nearby gulag, Norillag, in the 1920s and 30s. 60% of the present population is involved with the city’s industrial processes: mining, smelting, metallurgy and so on. The city sits on the world’s largest deposit of nickel-copper-palladium. Nearly half of the world’s palladium is mined in Norilsk. Accordingly, Norilsk is the 7th most polluted city in the world.

This documentary project aims to investigate human adaptation to extreme climate, environmental disaster and isolation. The living conditions of the people of Norilsk are unique, making them an incomparable subject for such a study.”

Chernyshova offers the following about the image of monumental architecture (with a blue suffusing light): The construction plan of Norilsk was established in 1940, by architects imprisoned in the nearby Gulag. The idea was to create an ideal city. The most “ancient” buildings are constructed in the Stalinist style. The next step of construction happened in the 60s, when the prevailing method in the USSR was to use pre-built panels.

Her other writings also allude to the disputed, if not adversarial, stories that meet and intersect in Days of Night / Nights of Day. The scene with the car and hazy clouds the colour of sulfur has the following notation: In the summer, there is a period when the sun doesn’t go under the horizon. This continues from the end of May till the end of July. It is accompanied by good weather and pleasant temperatures. Around 3 am, while the city sleeps, it is still illuminated by the sun. The city seems like a ghost town, emptied of its inhabitants.

One of the images I’ve included from Chernyshova’s series is unlike the others: and its difference helps to offer insight into the whole. Again, Chernyshova’s voice must be borrowed: Anna Vasilievna Bigus, 88, [who] spent ten years of her youth in the Gulag. At age 19, she was separated from her family and sent into the Arctic Circle. “The only joy we could have in Gulag was singing. We sang a lot. And this gave us the strength to survive…” Her daughter became a music teacher and her grandchildren sing in opera.

The complete series (produced with the support of The Jean-Luc Lagardère Foundation) can be seen here and a feature from LensCulture (where Chernyshova offers some words about many of the images I’ve shared here, that offer more nuance and depth to her vision) can be enjoyed here.

Elena Chernyshova’s site

@elena.chernyshova.photography

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Haruko Maeda | Self – Portrait with my cat and my grandmother in a glass, 2020

December 2, 2022Haruko Maeda | Self – Portrait with my cat and my grandmother in a glass, 2020

Several years ago, when I was going through the library of a recently deceased friend – at the invitation of his daughter – I noticed in his (former) apartment that she had a velvety bag, looking lustrous and fancy. I asked if this was some expensive alcohol, to mark her father’s passing. She told me it was her father’s ashes. When I asked if they’d be scattered in the city we were in, as he’d lived there for some time, contributing to the critical writing community and being a significant voice around visual culture and especially photography, or back in his home province in the Maritimes, she tersely commented she had not decided yet whether they’d be flushed down the toilet or mixed in with the cat litter.

When my own father passed several years ago, not long before COVID, the arrangements around his inurnment were put on hold: his ashes sat on a shelf in the living room of what is now my mother’s house for some time, only recently being put underground this past summer. Frankly, having ‘him’ in the same room where he spent most of the final years of his life seemed to comfort my mother: he was more agreeable than he’d been in decades, ahem.

No, I am not smiling – my face is as stoic and unreadable as Maeda’s, in her painting.

Those are both dark places to begin in considering Haruko Maeda’s painting Self – Portrait with my cat and my grandmother in a glass: but the funerary rites and rituals of family are nothing if not contested narratives that bring feelings to the surface, re opening old wounds and making new ones. Leave the dead to bury the dead, they (Matthew and Luke, to be specific, but that may just be hyperbole) say, but they never truly ‘leave’ us….

Maeda looks unperturbed in this scene: her cat seems relaxed, and even the fly that perches upon her arm that holds the ashes of her grandmother is subtle.

“Japanese Haruko Maeda lives and works in Austria since 2005. In her art she combines the Shintoistic traditions of her homeland with the Roman Catholic faith, deeply rooted in Austrian culture and history. This allows her to position herself between East and West. Maeda lets these double belongings function as a kind of filter through which she can process her own memories and experiences. The purpose is to raise universal questions about existence, life and death.” (from here)

In Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series, the final story arc – The Wake – offers several vignettes as concluding narratives about death, loss and mourning. One of these involves a man cast into exile, after the death of his son, who gets lost in a desert that his guides will not name, as to do so is to invite disaster. Master Li finds a tiny kitten as a companion, a ward, perhaps, against the ghosts of the dead he encounters in the ashy, shifting sands. At some point he encounters the shade of his son, and this is their conversation:

“Father? I am your son. That is only a kitten. Why do you abandon me to chase after it?”

“When you were alive, you were all my joy. Now you are dead. I see you only in my dreams. And when I awake my pillow is wet with tears. The kitten is living, and it needs my help.”

There is a solemnity to Maeda’s work, but also just a touch of irreverence.

More of Haruko Maeda’s work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Jane Evelyn Atwood | TOO MUCH TIME: WOMEN IN PRISON, 2000

November 25, 2022Jane Evelyn Atwood, TROP DE PEINES: FEMMES EN PRISON, 2000, Éditions Albin Michel, Paris, France. (OUT OF PRINT)

Jane Evelyn Atwood, TOO MUCH TIME: WOMEN IN PRISON, 2000, Phaidon Press Ltd., London, England. (OUT OF PRINT)

“Curiosity was the initial spur. Surprise, shock and bewilderment soon took over. Rage propelled me along to the end.”

Too many times – and I’m sure I’m not alone in this – I have heard some well meaning dilettante assert that ‘art should be about beauty’ or ‘should only uplift us.’ In terms of that space where photography intersects with ideas of art and documentary – and not to mention history – something that comforts you is most likely wrong, if not simply pablum. When I’m sharing images on social media, there are some photographers I hesitate to post works from (as photography still carries the weight of being more ‘real’, thus can ‘offend’ as well as see yourself banned from those platforms): Gilles Peress is one of those, for his unflinching lens in places from Rwanda to the former Yugoslavia (“I don’t trust words. I trust pictures”), Gordon W. Gahan (specifically his images of the Vietnam War), Donna Ferrato (I was lucky enough to experience her groundbreaking series Living with the Enemy decades ago, in Windsor) or Martha Rosler (her House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home works that had their genesis in response to the Vietnam War (c.1967–72) but that she ‘revisited’ in 2004 and 2008, ‘updating’ them to Iraq and Afghanistan).

But the text I’ve selected for a Library Pick is something that is not ‘there’ but ‘here’, and in that respect is often – easily, repeatedly – ignored.

Jane Evelyn Atwood’s “monumental work on female incarceration, published in both French and English, took Atwood to forty prisons in nine different countries in Europe, Eastern Europe, and the United States. The access she managed to obtain inside some of the world’s worst penitentiaries and jails, including death row, make this ten-year undertaking the definitive photographic work on women in prison to date. Extensive texts include interviews with inmates and prison staff as well as Atwood’s own reminiscences and observations. The prize-winning photos in this book, including the story of an incarcerated woman giving birth while handcuffed, established Jane Evelyn Atwood as one of today’s leading documentary photographers.” (from her site)

Atwood has always used her camera as a means to tell stories too often not even dismissed but denied, and she has granted a level of dignity and consideration to those whom are too often not considered human but detritus.

A good friend is a theologian, but of the liberation theology vein: I enjoy talking with them, as their righteous anger is only matched by their ability to quote that repeatedly translated and edited text with a sense of the public good. I mention them as they once pointed out that in the New Testament, only one person was promised a place in the ‘kingdom of heaven’, and that was one of the criminals being crucified at the same time as Jesus.

In a more modern sense, I might cite Lutheran Minister (and ‘public theologian’) Nadia Bolz-Weber‘s contemporary addendum to the beatitudes, which include ‘Blessed are those who have nothing to offer. Blessed are they for whom nothing seems to be working.’

Atwood published ten books of her work and been awarded the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography, the Grand Prix Paris Match for Photojournalism, the Oskar Barnack Award, the Alfred Eisenstadt Award and the Hasselblad Foundation Grant twice.

More of Atwood’s work can be seen here.

Like several of the books I’ve recommended, this is one I came across in my local library.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Arthur Tress: Fantastic Voyage, Photographs 1956-2000 | 2001

November 10, 2022Arthur Tress: Fantastic Voyage, Photographs 1956-2000

200 pages, Hardcover, Bulfinch, 2001.

Arthur Tress (Photographer), with writing by John Wood and Richard Lorenz

There was a recent exhibition of Tress’ photographs mounted at Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto, and that brought his work back to mind. Having enjoyed several of his books, I returned to this one – which is, for me the definitive publication of Tress’ art and aesthetic – and it’s definitely worthy of a Library Pick.

Tress’ works are striking, if unsettling. An initial amusement or facile reading gives way to a more conflicting or uncanny narrative upon closer consideration. He shares this with photographers like Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Mary Ellen Mark, Diane Arbus and – an artist featured in a previous Library Pick – Roger Ballen.

“Tress started out as an ethnographic documentarian but, partly inspired by the rituals he recorded, turned to ever more premeditated subjects. In an early project, he asked New York children to tell him their dreams and then posed them, with appropriate trappings, in neighborhood spaces to illustrate their sleeping fancies. His projects since the mid-1980s involve arrangements of tools, toys, furniture, dolls, and other stuff that Tress paints and lights to suggest scenarios and even narratives. Besides the short-term projects, Tress has made surrealist outdoor still lifes and male nudes over longer periods. The latter, including some of his best-known pictures, are implicitly homoerotic but considerably more apprehensive and even dread-filled than the nudes of fellow gay surrealist Duane Michals. But there is more humor and less darkness in Tress’ highly polished work…” (from Tress’ site, which is worth spending some time exploring, as well)

“Arthur Tress’s career can be seen as a long fantastic voyage – from early photojournalism into the realm of surrealism, eroticism and miniature worlds. This retrospective is an overview of Tress’s career. As the title implies, Tress’s work is full of fantasy – nothing is what it at first seems. His images contain dark undercurrents and light wit, violence and beauty, futuristic scenes and homoerotic and psychologically charged tableaux. The 250 images featured in this volume range from the early black-and-white work to the richly coloured surrealistic images of the 1990s and his latest, previously unpublished work in progress. Richard Lorenz, (curator of a retrospective exhibition in Washington, DC, in May 2001) offers an in-depth biographical essay on Tress and the development of his vision. An essay by noted photo critic John August Wood puts Tress in context.” (from here)

The images I’ve shared here are from the bodies of work by Tress that are my favourites – primarily Dream Collector (1970 – 74), Theater of the Mind (1976 – 77) and Still Life (1981 – 83): but there’s other series in this book that are very different, and a testimony to the breadth of his aesthetic and career. These include the starkness of his documentary work in Appalachia (1969) to the uncanny quality of his Fishtank ‘installations’ (1989) to the moribund garishness of Hospital (1985 – 87).

From the Corcoran’s review of this publication: “Tress’s work, above all else, reveals a personal approach to photography, a subjective view of the world that continually reinvents itself while it ponders universal archetypes and myths.”

Arthur Tress was a previously featured artist in AIH Studios’ ongoing Artists You Need To Know series: that can be enjoyed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

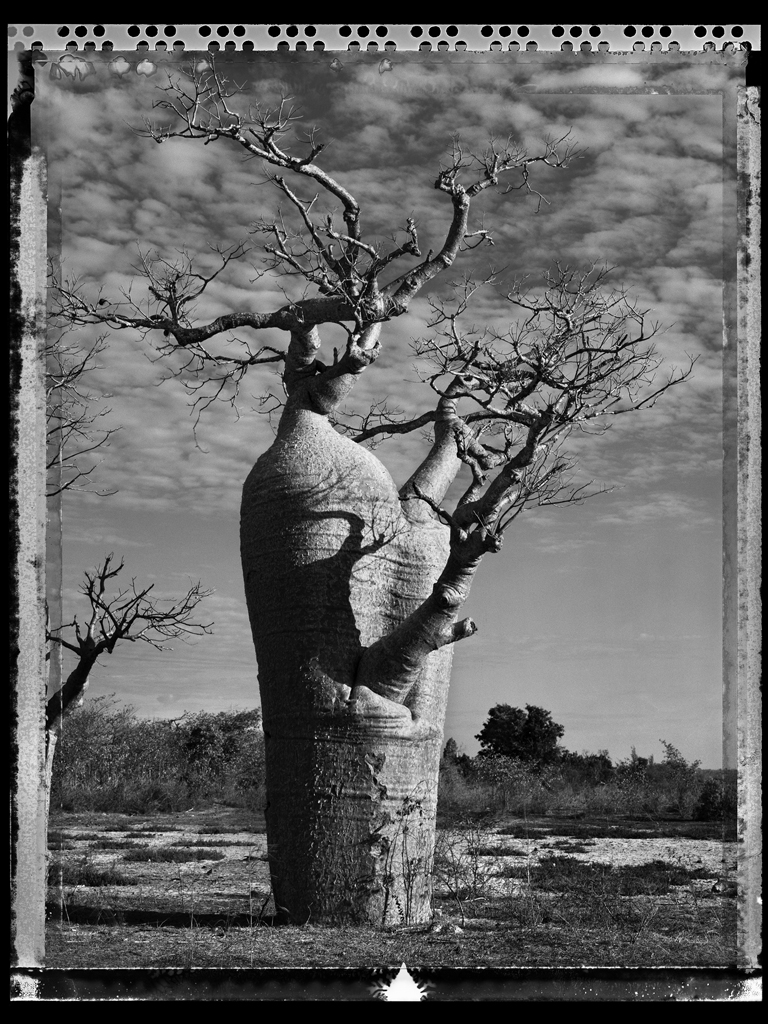

Elaine Ling | Baobab #31 – 2010, Madagascar

November 19, 2022Elaine Ling | Baobab #31 – 2010, Madagascar

Ce qui embellit le désert, dit le petit prince, c’est qu’il cache un puits quelque part…[What makes the desert beautiful, said the little prince, is that somewhere it hides a well…]

It is an odd feeling to encounter the work of an artist, seeing how prolific they are and be enamoured of their practice, then discover that they passed a few years ago. I’ve often had the same experience with authors (I have a habit of finding the work of a writer that is new to me, and consuming all the books, and it’s an empty sadness when you realize they won’t be creating any more).

This image is one from a series titled Baobob, by the late Elaine Ling (1946-2016). At her site it is the final series presented, from an extensive and enthralling body of work.

It can be read as having the quality of an epitaph: these massive, seemingly eternal natural ‘monuments’ that have survived her, and will likely survive all of us.

In that manner I have of being ‘too subjective’, Baobob trees remind me of Antoine de Saint Exupéry’s novel Le Petit Prince (1943): to me, it’s a melancholy story, about loss and death, with touching moments of truth that have contributed to how it – despite often being considered a story for children – speaks to many adults, like myself.

“Seeking the solitude of deserts and abandoned architectures of ancient cultures, Elaine Ling…explored the shifting equilibrium between nature and the man-made across four continents. Photographing in the deserts of Mongolia, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Timbuktu, Namibia, North Africa, India, South America, Australia, American Southwest; the citadels of Ethiopia, San Agustin, Persepolis, Petra, Cappadocia, Machu Picchu, Angkor Wat, Great Zimbabwe, Abu Simbel; and the Buddhist centres of Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Tibet, and Bhutan; she has captured that dialogue.” (from her site)

Voici mon secret. Il est très simple: on ne voit bien qu’avec le cœur. L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux [Here is my secret. It is very simple: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye].

On the first of August, 2016, Elain Ling lost her battle with lung cancer: her brother – Edward Pong – has indicated that he intends to continue to foster her legacy, through the maintenance of Ling’s site.

It is an impressive space with much more about Ling’s life and work – and many more of her moments from her life and around the world – that can be enjoyed here. C’est véritablement utile puisque c’est joli [It is truly useful since it is beautiful].

All quotes in italics are from Saint Exupéry’s The Little Prince .

Elaine Ling was also a recently featured Artist You Need To Know, in AIH Studios’ continuing series. You can enjoy that here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Eleanor Antin | 100 Boots, 1971-73

October 28, 2022Eleanor Antin | 100 Boots, 1971-73

“For month after month after month, her five-score empty rubber boots had to be carted across the country, set up in various evocative spots, and then photographed before someone could come along and chase Antin away…at the time, the empty boots would have had immediate resonance as a reference to the Vietnam War, and to the boot-wearers who would never come home.” (Blake Gopnik)

Eleanor Antin is an artist who has not, in my opinion, received the credit she merits for her performative installations and photographs that have a cinematic quality. At the risk of being flippant, if Gopnik, Camille Paglia and I myself all agree as to her importance, we surely can’t be wrong. Antin has been making work since the 1960s, and her art often intersects with politics in both overt and covert ways.

From Paglia’s Glittering Images: A Journey through Art from Egypt to Star Wars: ‘As a work of Conceptual art, 100 Boots consisted of temporary on-site sculptural installations documented by photographs (taken by Philip Steinmetz), which were sent uninvited to a distant, dispersed audience. The formal, squadron-like patterns assumed by the boots parody the frigid geometries then being made by male Minimalist sculptors. In their outdoor placement, the boots evoke traditional landscape painting as well as the new genre of land art, which was just emerging from Minimalism. Antin strategically varied the look of the cards so that “seductively beautiful” images were not the rule. Most of them have a bleak desolation reminiscent of existential European art films. Indeed, Antin saw the work as “a movie composed of still photos”.’

Over her career, Antin ‘has utilized a staggering range of styles, media, and materials, and her work has combined theater, dance, literature, drawing, painting, sculpture, crafts, photography, video, and architecture. “All artworks are conceptual machines,” she said. And again: “All art exists in the mind.” Antin deeply influenced the emergence of both performance art and Conceptual photography.’

For myself, these images are about the insidious nature of loss, especially as it pertains to those who have died during the pandemic. Empty boots that take on the nature of ghosts that appear in any place at any time, a simple – almost banal, like a rubber boot – fact of absence that hits you like a hammer to the chest and requires you to sit down to consider it….

Eleanor Antin was a previously featured Artist You Need To Know, in AIH Studios’ continuing series. That can be enjoyed here.

More works from this series can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

HAUNTED | DREAMING | CITY | STEVEN LAURIE

December 30, 2022HAUNTED | DREAMING | CITY | STEVEN LAURIE HAUNTED | DREAMING | CITY | STEVEN LAURIE @_steven_laurie_ @stevenlaurie_bw Steven Laurie Photography... Read More

The Sketchbooks of Tom Forrestall

October 13, 2022curated.’s Virgil Hammock offers some thoughts on the voluminous and impressive notebooks of Canadian artist Tom Forrestall in tandem with an exhibition titled The Sketchbooks of Tom Forrestall at The Saint Johns Art Centre.

Read More

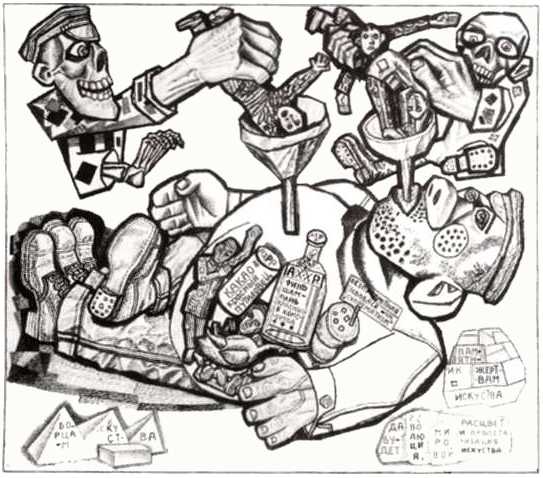

Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

October 21, 2022Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

He was walking about with a noose round his neck and didn’t know. So I told him what I’d heard about his poems.

. . . . . . . .

Yevgraf: This is a new edition of the Lara poems.

Engineer: Yes, I know. We admire your brother very much.

Yevgraf: Yes, everybody seems to.. now.

Engineer: Well, we couldn’t admire him when we weren’t allowed to read him…

Yevgraf: …No.

(both quotes from Boris Pasternak’s tale of Russia before and after the Russian Revolution Dr. Zhivago)

A defining book in my reading and understanding of art history in the 20th century is Boris Groys’ The Total Art of Stalinism: begun when the USSR was still in existence, Groys was able, with the fall of that empire, to access more information, and offer a more nuanced take upon the years post Russian Revolution, as it pertains to the arts in that rare and unique historical moment. Amusingly, I became aware of it after participating in a panel about modernism, and horrifying my fellow speakers by stating that it had failed, horribly, but that its relevance was in its ideals…

Several points stay with me, in considering Pavel Filonov’s work. One is that, in a correlation to the backward economic state of Russia making it fertile ground for a radical new approach and the subsequent revolution, the artistic milieu also suffered from this. It’s not incidental that so many significant artists – not just to Russia but to ‘western’ art history – like Malevich or the Suprematists flourished during the first heady days of the NEP. Experimentation and a sentiment that ‘anything was possible’ was pervasive and defining, with a desire to irrevocably fracture from the ‘old.’

This, of course, all ended badly, and the promised freedoms – whether artistic or personal – were soon not just reigned in, but suppressed, and a cultural exodus from the USSR to other places was predictable.

Filonov (1883 – 1941) served in WWI and would die of starvation during the siege of Leningrad, the once and present St. Petersburg, in the war that followed the ‘war to end all wars.’

The painter, art theorist and poet was an outsider, even during the pre and immediately post revolutionary days of promise: after several failures, in “1908 Filonov was admitted at last to the Academy of Arts. His works attracted the attention of both students and professors by their unusualness: they were not abstract and depicted their subject with full likeness, but were executed in garish, bright colors – reds, blues, greens and oranges. This manner did not conform to the Academy standards, and Filonov was dismissed “for influencing students with the lewdness of his work”. Filonov protested the decision of the rector Beklemishev, and was rehabilitated, but after studying for two years he left the Academy in 1910.”

He was one of many whose works were deemed degenerate, as they eschewed official socialist realist policy. He’d be lost to us, in terms of history, but for the efforts of his sister Yevdokiya Nikolayevna Glebova: “She stored the paintings in the Russian Museum’s archives and eventually donated them as a gift. Exhibitions of Filonov’s work were forbidden. In 1967, an exhibition of Filonov’s works in Novosibirsk was permitted. In 1988, his work was allowed in the Russian Museum. In 1989 and 1990, the first international exhibition of Filonov’s work was held in Paris.

During the period of half-legal status of Filonov’s works it was seemingly easy to steal them; however, there was a legend that Filonov’s ghost protected his art and anybody trying to steal his paintings or to smuggle them abroad would soon die, become paralyzed, or have a similar misfortune.”

It’s unsurprising that Filonov was deeply influence by fellow dissident Klebnikov: and his works – whether the obvious disdain present in this piece The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, or the more stark Those Who Have Nothing To Lose, or Animals, that would make a fine illustration for Orwell’s Animal Farm decades later – have an unflinching quality.

More of Filinov’s life and legacy can be learned here (and was the source cited for the biographical quotes about his life and work).

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Asya Kozina | Baroque Paper Wigs, 2016

October 14, 2022Asya Kozina | Baroque Paper Wigs, 2016

Historical wigs always fascinated me, especially the Baroque era. This is art for art’s sake aesthetics for aesthetics, no practical sense. But they are beautiful. I made a series of wigs. Paper helps to highlight in this case the main form and not be obsessed [with] unnecessary details.

There is something both decadent and timeless about Kozina’s work. The idea of a peformative lens comes into play – as these intricate, hand made (with no digital tools) ‘wigs’ only attain their ultimate beauty when worn by one of Kozina’s models, and the rest of the team comes together (meshing together, perhaps, like the paper in the artist’s constructions) to produce a moment that has as much to do with art historical tropes, as seen in the paintings of Jacques Louis David or Caravaggio, as it does with contemporary couture and fashion. The artifice of the apple, the pale face perfectly dotted with subtle spots of rouge, the winsome look eschewing eye contact in one scene and the feigned precociousness of the model looking directly at us in another all suggest this might be a Jean-Honoré Fragonard (more late Baroque, with a touch of the playfulness of Rococo) except for the stark palette, only broken by the red of the apple.

I think of Fragonard as the old Russian Imperial court often looked to France for its ideal, and there’s a sentiment of the elaborate, exotic Ancien Régime to Kozina’s many works: another act of imitation from an artifice of pretension that was, of course, all about social class and cultural capital.

But Kozina does more than just mimic: several bodies of work – such as the more ballistic Baroque Punk or more erotic Eve – employ the history of fashion as a starting point for contemporary considerations and conversations.

More of her work can be seen on IG at @asya_kozina or at her site.

The photographer for this work is Anastasia Andreeva, with assistance from Dina Kharitonova. The makeup artists are Marina Sysolyatina and Svetlana Dedushkina.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments