Barry Ace

Stepping into an exhibition by artist Barry Ace is a transformative experience. The bold colour palette, the textural combination of materials, and the meticulous attention to detail quickly captivates you. The entanglements of these elements reveal unique narratives that change the lens through which we see others.

My introduction to Ace’s work came in 2016 when I discovered Abinoojiiyens Ogichidea –Baby Warrior, a digital print representing a vintage baby doll with Anishinaabeg floral motifs as its clothing. The innocence of the delicately adorned object against the stark, white backdrop speaks intimately to collective early childhood struggles to reclaim Indigenous language and cultural identity. Through his clever manner of storytelling, Ace challenges the audience to re-evaluate preconceived perceptions and think more deeply about the world around us.

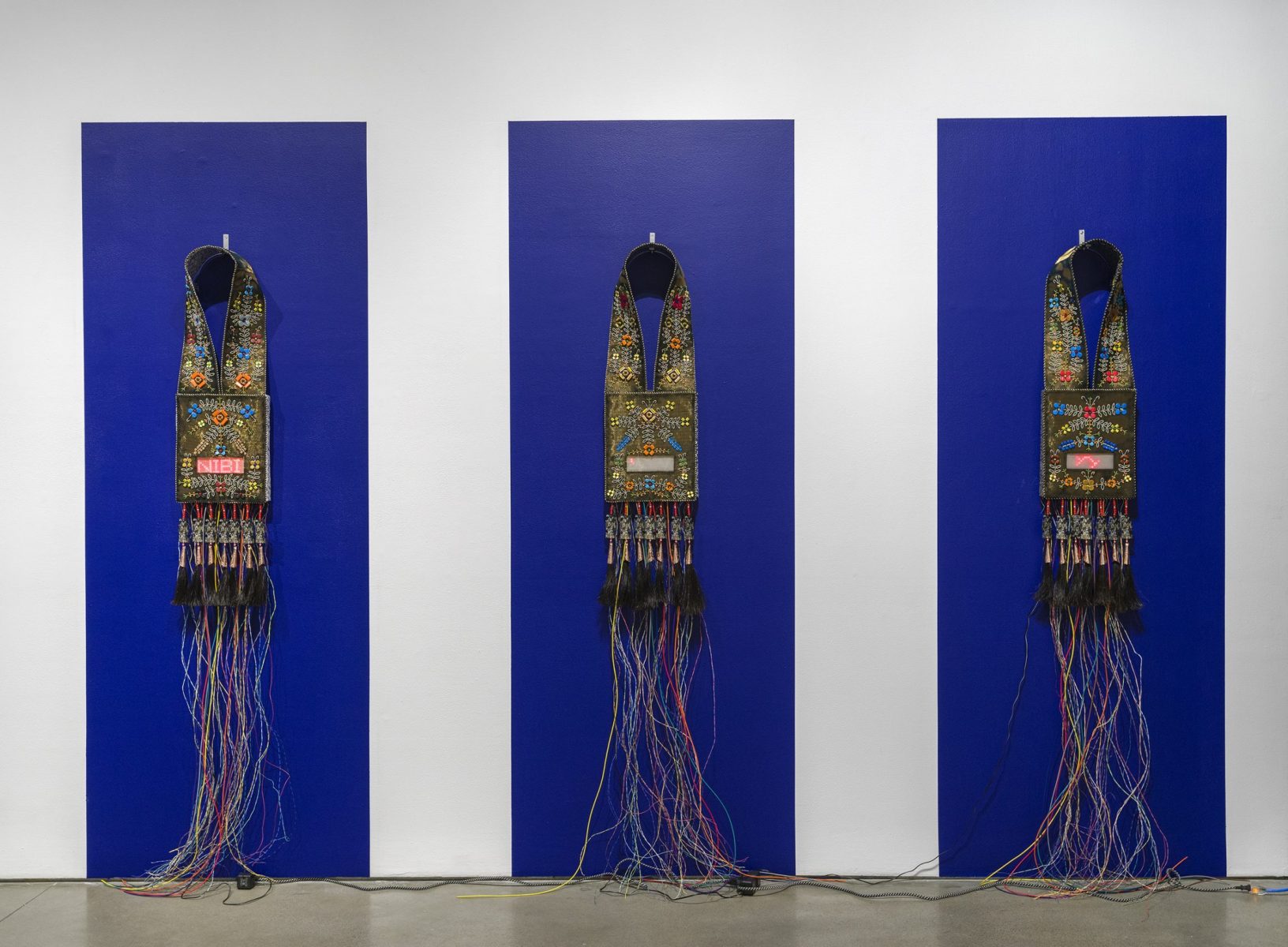

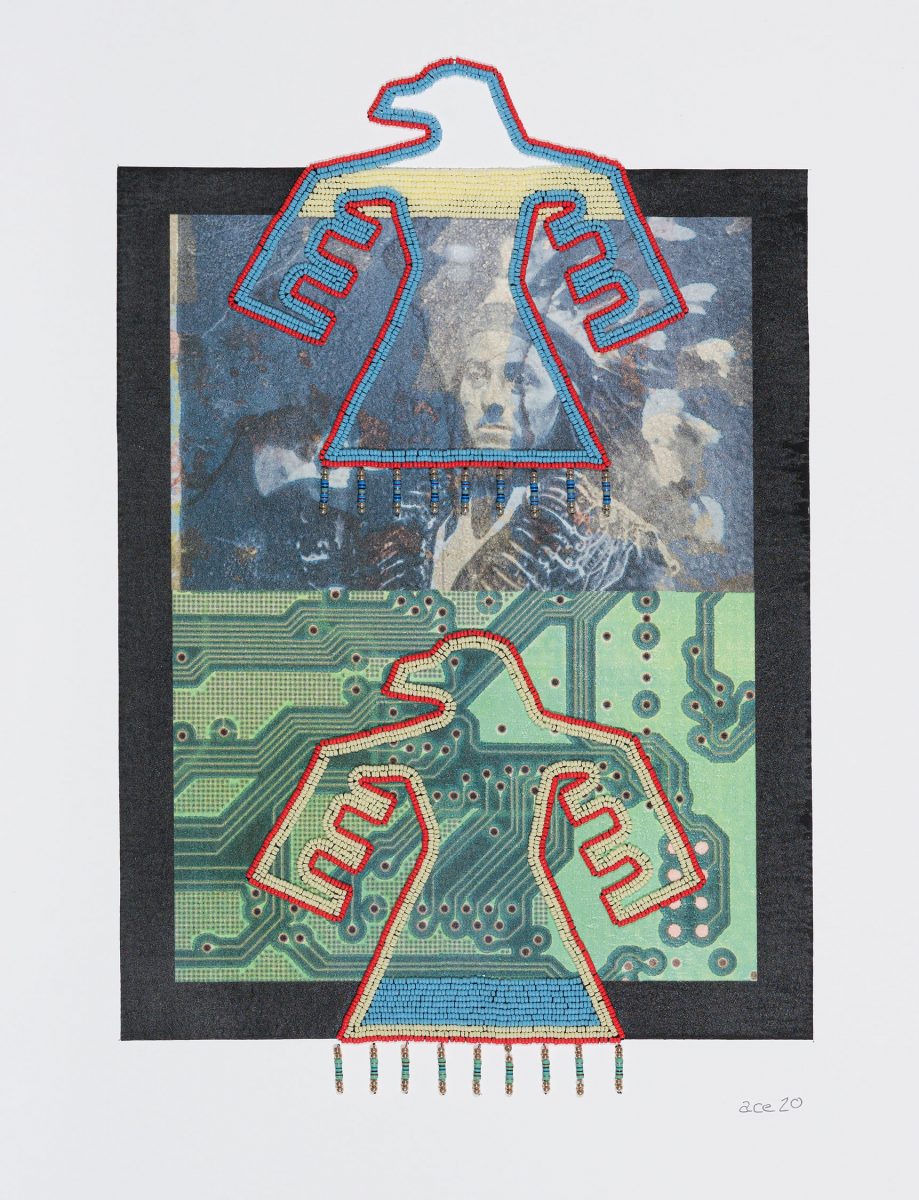

The exploration of cultural continuity, the impact of colonialism, and the convergence of the historical with the contemporary are recurring themes in Ace’s work. In his ongoing Bandolier Series, Ace infuses the past, present, and future into works that not only honour the distinct Anishinaabeg aesthetic but also speak to new ways of cultural expression.

Traditional bandolier bags were made by women and worn by men on the shoulder and across the body as part of celebratory ceremonial dress. Modelled from the pouches used by European soldiers, the bandolier soon morphed into different designs and materials depending on the region in which they were made. Women across the Great Lakes regions used glass seed beads obtained through trade with Europeans to embellish their bags. The intricacy of the designs and the amount of labour involved in producing a bag marked the personal exchange of bags as a sign of friendship and generosity.

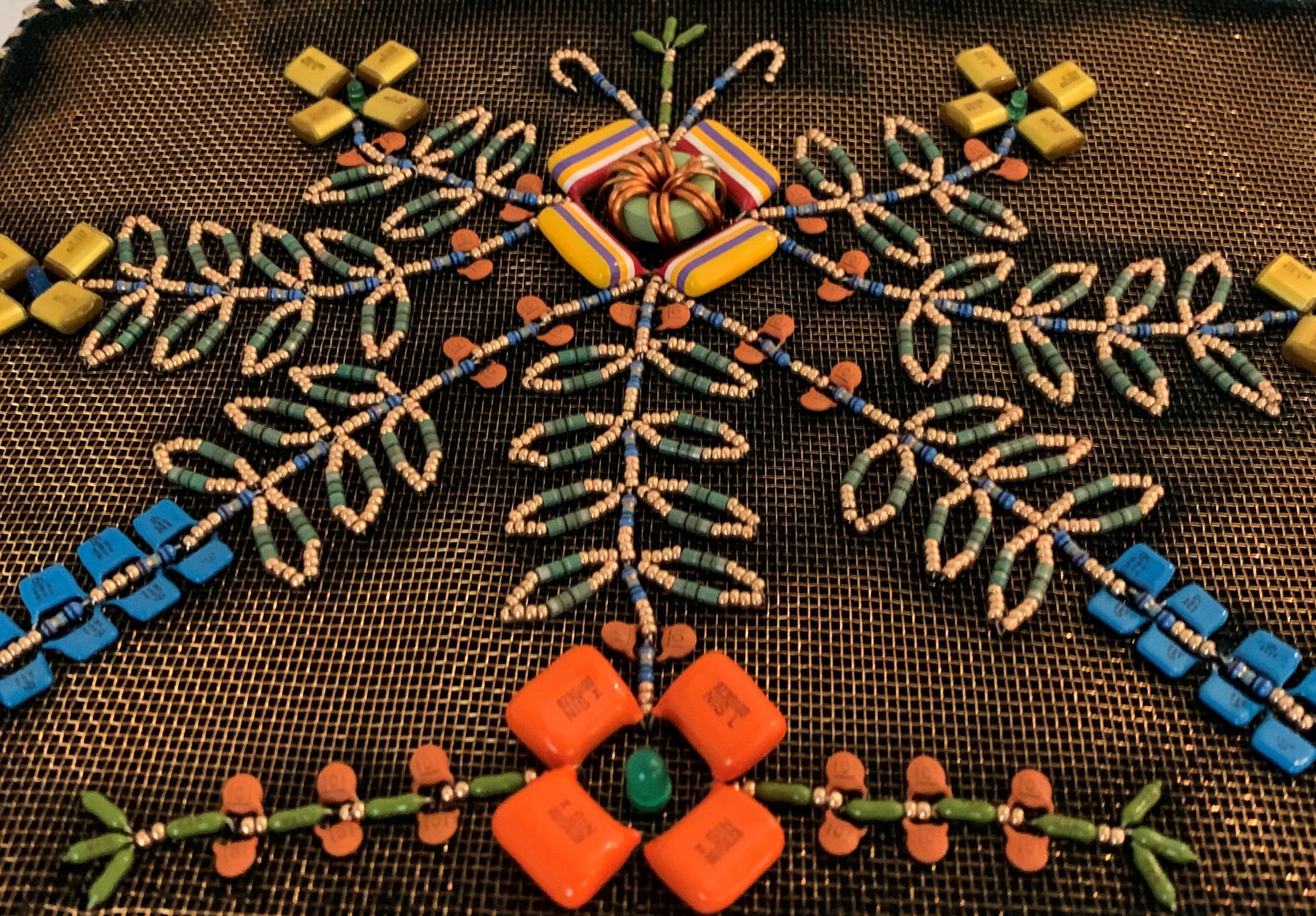

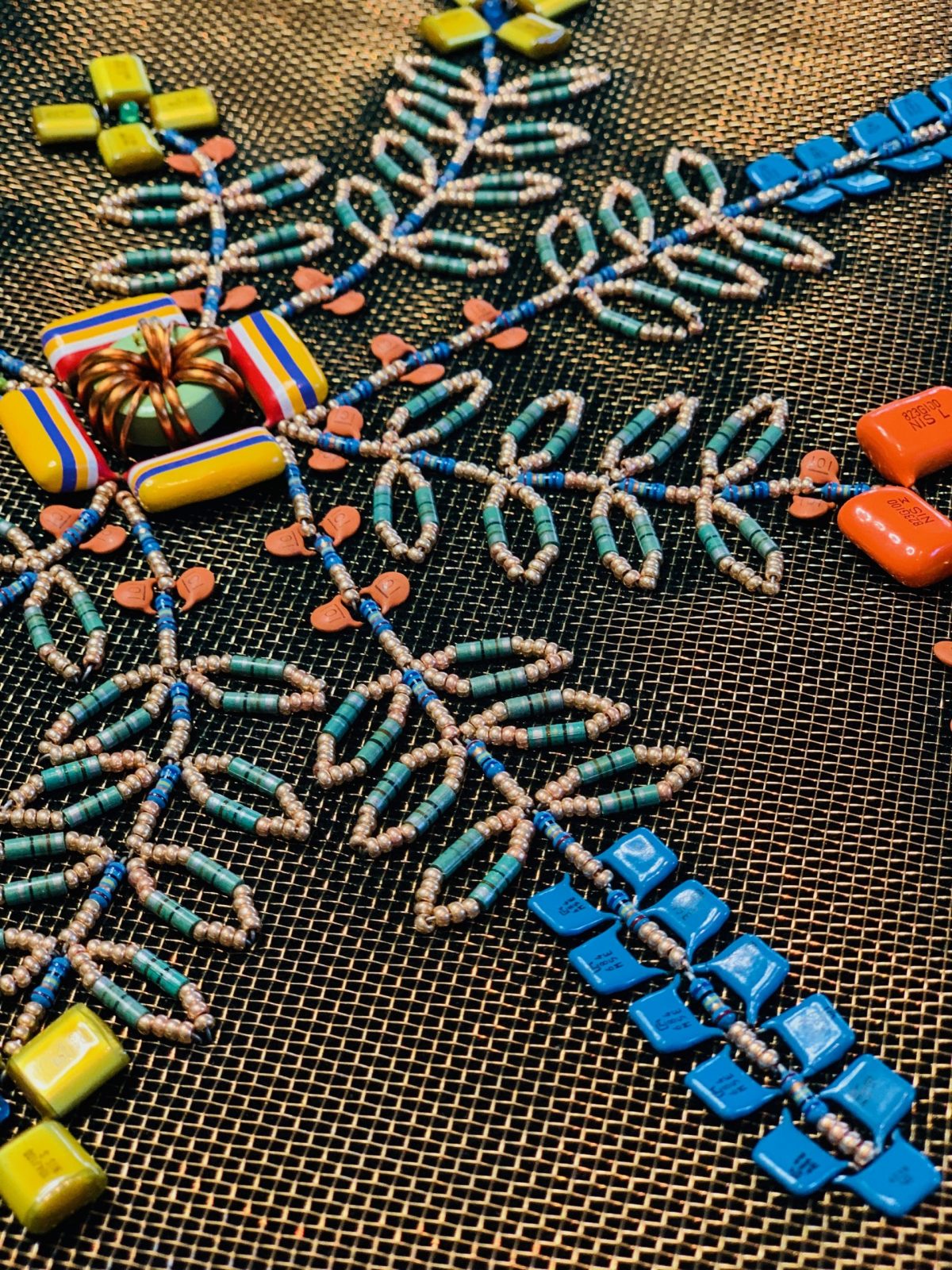

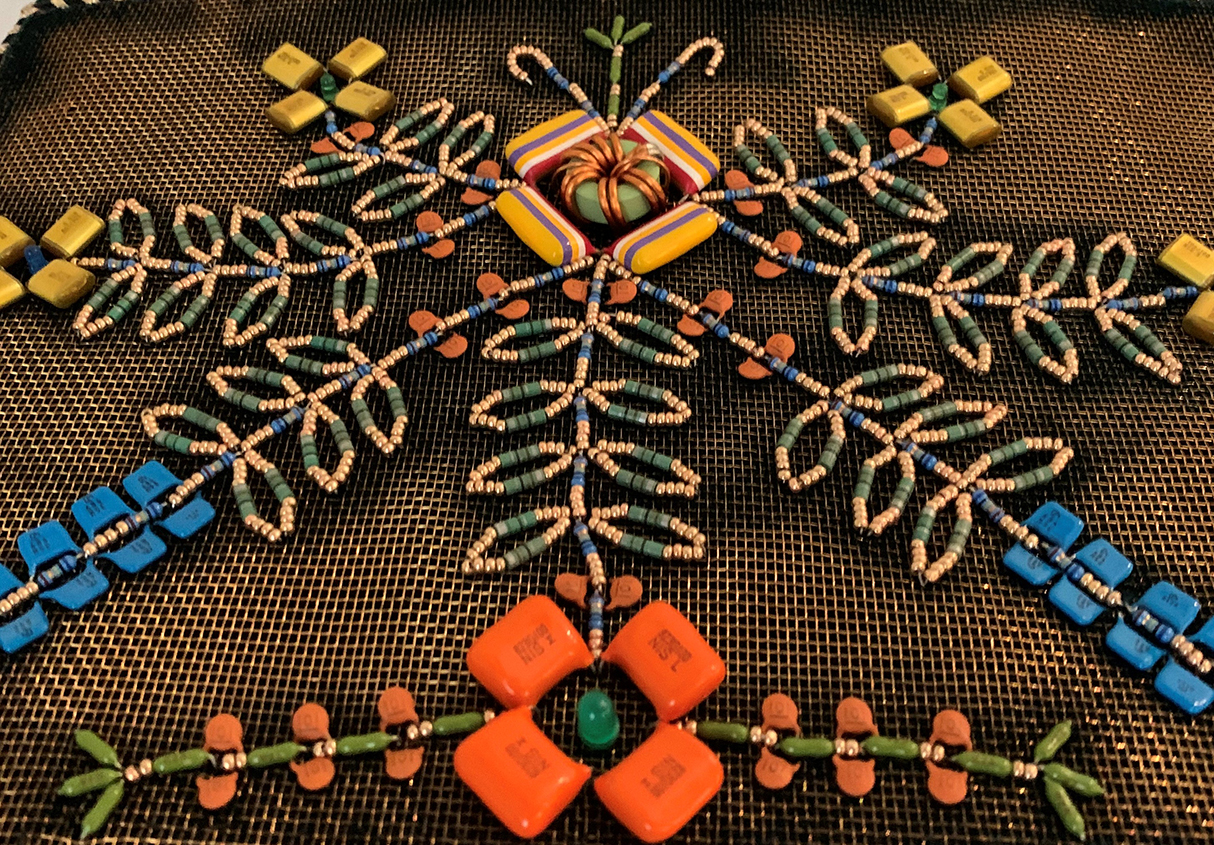

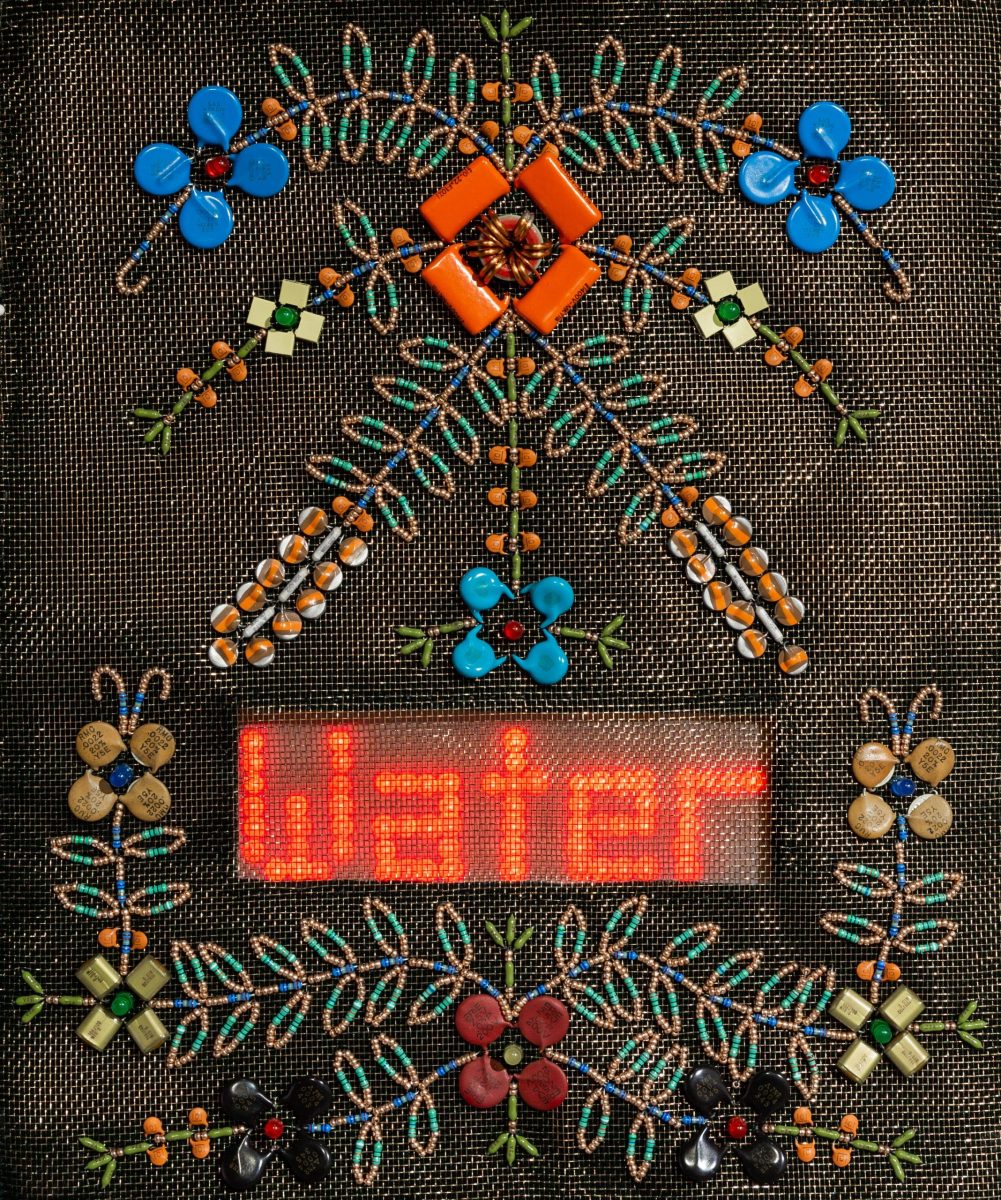

Ace ingeniously re-imagines this historic style of bag and moves its narrative into the twenty-first century. At first glance, his bandoliers appear representative of a typical bag enhanced with intricate woodland-style beadwork. After closer examination, however, the viewer is confronted with various salvaged electronic components: circuit boards, resistors, and capacitors simulate glass beading, and stripped cable wires mimic strands of horsehair. The floral references to medicinal flowers with infused healing properties are now re-created with capacitors and resistors, components which also store and release energy. This connection between past and present is enhanced by the digital tablets embedded in the center pockets of the bandoliers, each radiating messages that acknowledge the importance of the land, water, and wind. The combination of colours and materials create a modern vision of beauty.

The intentional fusion of traditional Anishinaabeg aesthetic with contemporary digital technology cunningly shifts the paradigm and materiality of the bandolier. Through the integration and juxtaposition of recognizable materials Ace alludes to the rejection of cultural stasis and highlights the importance of the continuum of Anishinaabeg material culture.

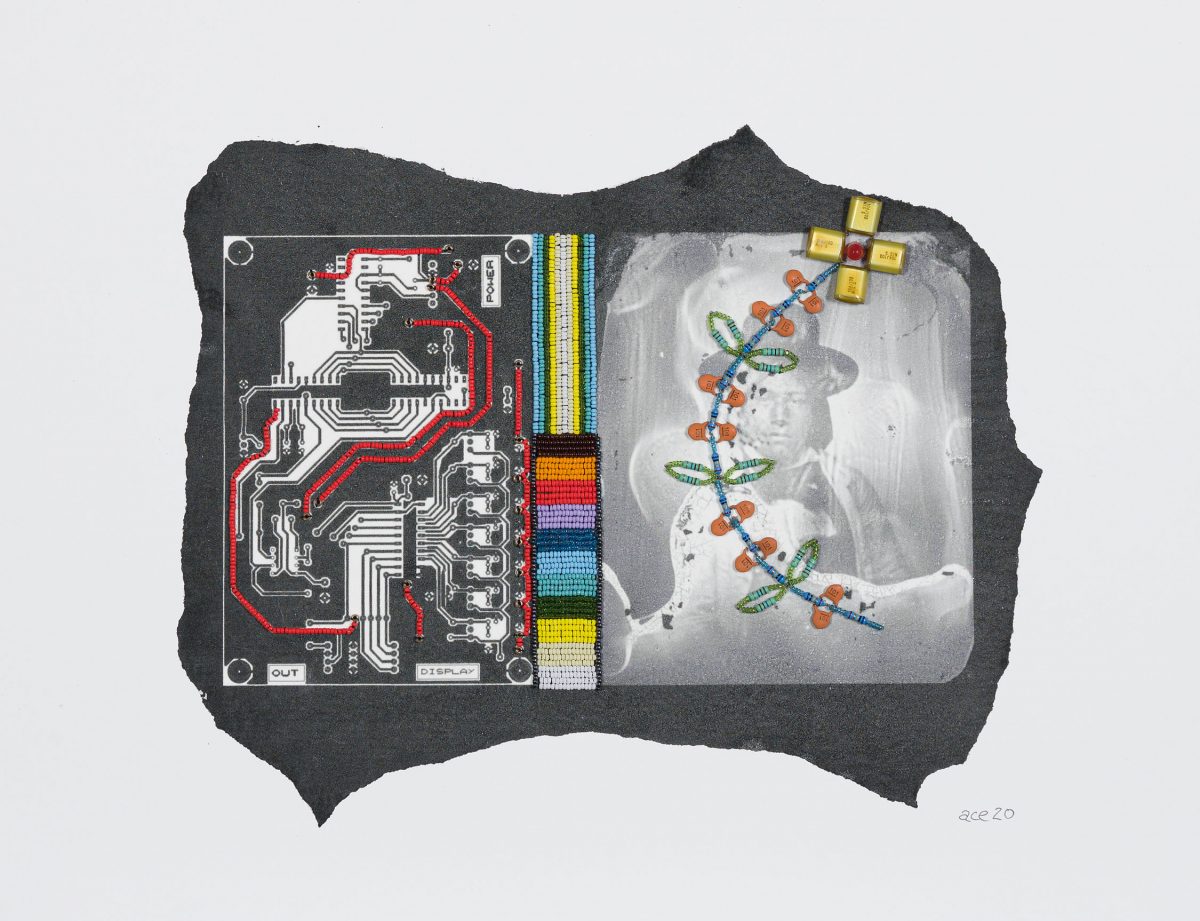

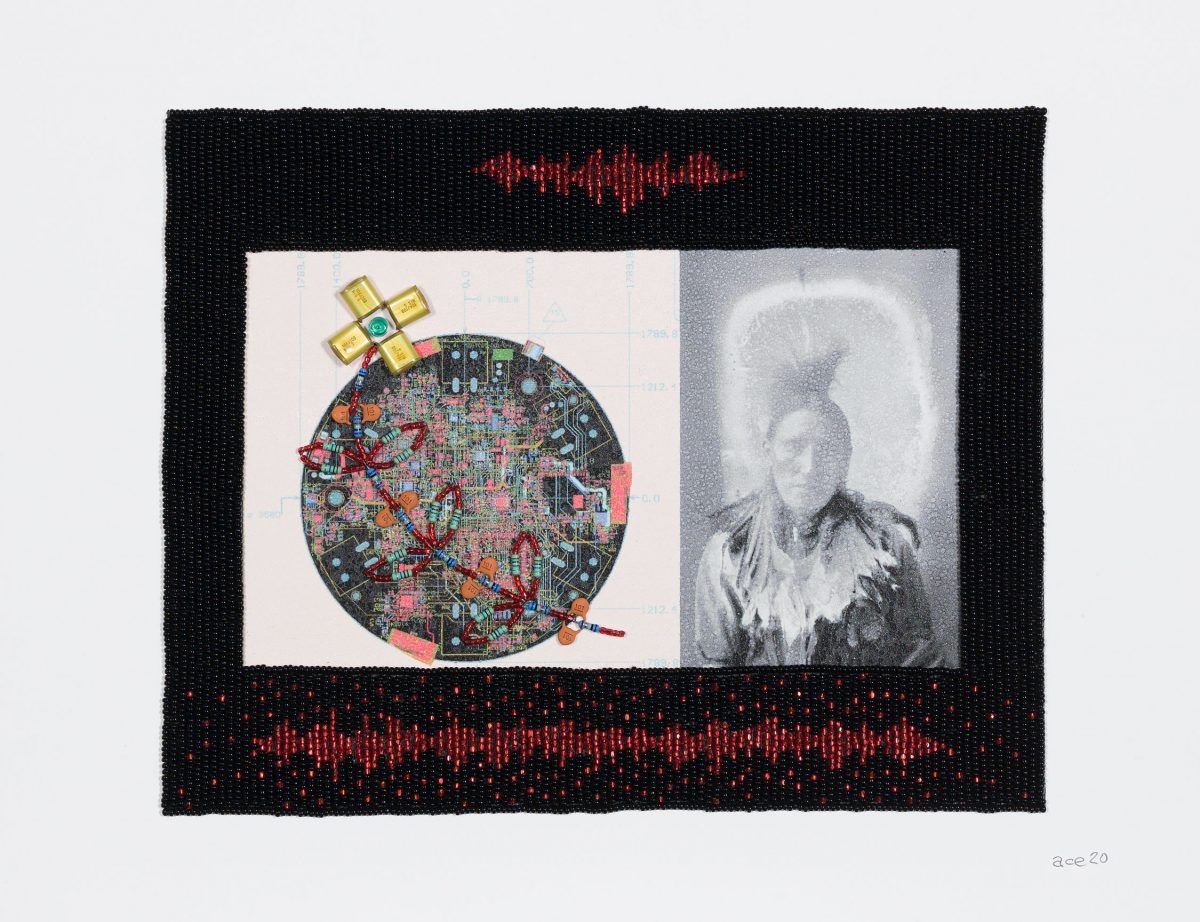

Ace’s recent body of work entitled The Covid-19 Suite continues his exploration of cultural identity and survivance1. In reaction to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and self-imposed isolation, Ace created 19 mixed-media works that address individual and collective perseverance. Layering archival and personal portraits of Indigenous survivors of past global pandemics with glass beading and electronic circuitry, Ace once again displays his masterful knowledge-sharing ability to move the past into the present.

Titles of the works from this series include Protection, Transmission, Pathogen, and Influenza—setting the stage for viewers to reflect on the medical and social inequalities to basic needs that impact Indigenous and marginalized communities, both historical and contemporary. In Protection, the portrait of Maungwudaus (Great Hero), an Indigenous rights advocate, knowledge keeper, and performer looks to the viewer through the beaded frame of a thunderbird. The founder of a First Nations dance troupe, Maungwudaus spent most of his life travelling and entertaining dignitaries across Europe. He was immunized against smallpox and survived the pandemic of 1870–74, but many of the dancers did not.

In Transmission and Pathogen, unidentified Indigenous men appear soundless to share their story but the careful placement of beaded sound waves and circuitry panels provides the bridge to voice their messages from the past to the present. Lastly, Influenza takes a personal look at Ace’s family members who lived through and survived the deadly Influenza Pandemic (1918–20). Approximately 500 million people became infected with the virus, causing an estimated 50 million deaths worldwide. In Influenza, Ace juxtaposes his great-aunt Melvina lovingly holding his father Cecil next to a newspaper headline that reads “those who are most susceptible to it” a clear reference to the medical injustices and lack of attention given to Indigenous health care. The COVID-19 Suite exemplifies Ace’s continuing mastery in employing Anishinaabeg iconography to reveal intergenerational connections.

There is never an easy or straightforward way to honour one’s heritage and acknowledge past history. Ultimately, you strive to share a narrative that will impart knowledge, express the uniqueness of your cultural identity, and recognize the generational traditions that have helped to formulate who you have become. Barry Ace not only achieves these goals but goes beyond to reconstruct notions of Indigenous art-making and challenge viewers to re-examine notions of cultural stasis in the most eloquent and beautiful way.

1.Coined by Anishinaabeg scholar Gerald Vizenor, survivance is an active sense of presence over historical absence and describes the Indigenous perseverance to survive and take an active role in resisting the pressures of colonialism.

More detailed information about the works of Barry Ace in this article:

Abinoojiiyens Ogichidaa – Baby Warrior, 2000 (acrylic, plaster on plastic doll, 25 x 10 x 10 cm)

Bandoliers for Aki, Noodin, Niibish (installation shot), 2019 (bronze screen, velvet, electronic components, LED scrolling messenger devices, metal, paper, plastic, metal, copper, calico, synthetic material) Photo: Courtesy of Guy L’Heureux

Bandoliers for Noodin, 2019 (bronze screen, velvet, electronic components, LED scrolling messenger devices, metal, paper, plastic, metal, copper, calico, synthetic material, 116 x 40 x 10 cm) Photo: Courtesy of Guy L’Heureux

Bandoliers for Niibish, 2019 (bronze screen, velvet, electronic components, LED scrolling messenger devices, metal, paper, plastic, metal, copper, calico, synthetic material, 116 x 40 x 10 cm) Photo: Courtesy of Guy L’Heureux

Bandoliers Details, 2019 (bronze screen, velvet, electronic components, LED scrolling messenger devices, metal, paper, plastic, metal, copper, calico, synthetic material) Photo: Courtesy of Guy L’Heureux

Covid-19 Suite – Pathogen, 2020 (Photo transfer, electronic components, glass beads on paper, 27 x 34.9 cm) Photo: Courtesy of Heffel

Covid-19 Suite – Protection, 2020 (Photo transfer, electronic components, glass beads on paper, 27 x 34.9 cm) Photo: Courtesy of Heffel

Covid-19 Suite – Resuscitate, 2020 (Photo transfer, electronic components, glass beads on paper, 27 x 34.9 cm) Photo: Courtesy of Heffel

Artist

Barry Ace is a practicing visual artist currently living in Ottawa, Canada. He is a debendaagzijig (citizen) of M’Chigeeng First Nation, Odawa Mnis (Manitoulin Island), Ontario, Canada. His mixed-media paintings and assemblage textile works infuse Anishinaabeg culture (and other global cultures) with new technologies, bridging historical and contemporary knowledge, art, and power.

His work has been included in numerous group and solo exhibitions, including: Emergence from the Shadows – First Peoples Photographic Perspectives Canadian Museum of Civilization (1999: Gatineau, Quebec); Urban Myths: Aboriginal Artists in the City. Karsh-Masson Gallery (2000: Ottawa, Ontario); The Dress Show, Leonard and Ellen Bina Art Gallery (2003: Montréal, Quebec); Super Phat Nish, Art Gallery of Southwestern Manitoba (2006: Brandon, Manitoba); 50 Years of Pow wow, Castle Gallery (2006: New Rochelle, New York); Playing Tricks, American Indian Community House Gallery (2006: New York, New York); “m∂ntu’c – little spirits, little powers” Nordamerika Native Museum (2010: Zurich, Switzerland); Changing Hands 3 – Art Without Reservations (2012 -2014: Museum of Art and Design: New York, New York); and Native Fashion Now: North American Native Style (2016 – 2017: Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts); Anishinaabeg Art and Power, Royal Ontario Museum (2017: Toronto, Ontario); Every. Now. Then. Reframing Nationhood, Art Gallery of Ontario (2017: Toronto, Ontario); 2017 Canadian Biennial, National Gallery of Canada (2017: Ottawa, Ontario); We’ll All Become Stories, Ottawa Art Gallery (2018: Ottawa, Ontario); URL : IRL, Dunlop Art Gallery (2018: Regina, Saskatchewan); Public Disturbance: Politics and Protest in Contemporary Indigenous Art from Canada, Supermarket 2018 (2018: Stockholm, Sweden); Coalesce, Robert Langen Gallery (2019: Waterloo, Ontario); Carbon and Light: Juan Geuer’s Luminous Precision, Ottawa Art Gallery (2019: Ottawa, Ontario); Wrapped In Culture, Ottawa Art Gallery (2019: Ottawa, Ontario); Body of Waters, Idea Exchange (2019: Cambridge, Ontario); Abadakone, National Gallery of Canada (2019: Ottawa, Ontario); and mazinigwaaso / to bead something, Faculty of Fine Art Gallery Concordia University (2019: Montreal, Quebec).

His work can also be found in various public and private collections in Canada and abroad, including the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa, Ontario); Canadian Museum of History (Gatineau, Québec); Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto, Ontario); Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto, Ontario); Government of Ontario Art Collection (Toronto, Ontario); City of Ottawa (Ottawa, Ontario); Ottawa Art Gallery (Ottawa, Ontario); Woodland Cultural Centre (Brantford, Ontario); Canada Council Art Bank (Ottawa, Ontario); North American Native Museum (Zurich, Switzerland); Ojibwe Cultural Foundation (M’Chigeeng, Ontario); Global Affairs Canada (Ottawa, Ontario); TD Bank Art Collection (Toronto, Ontario); Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (Gatineau, Québec); and Westerkirk Works of Art (Toronto, Ontario).

Barry was the recipient of the 2015 KM Hunter Visual Artist Award from the Ontario Arts Council.

Links

Website: https://www.barryacearts.com/

~ Posted by Suzanne Luke