Cree Tylee

``...now I am rampant with memory....``

To be honest, and all the external influences aside, there are some parts of this that I remember in great, terrible detail, so much so I fear getting lost in the labyrinth of memory. There are other parts of this that remain as unclear and unknowable as someone else’s mind, and I fear that in my head I’ve likely conflated and compressed timelines and events. (Paul Tremblay, A Head Full of Ghosts)

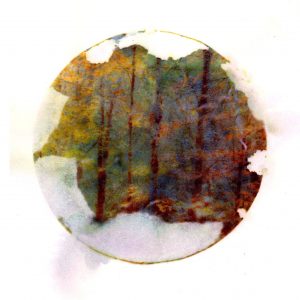

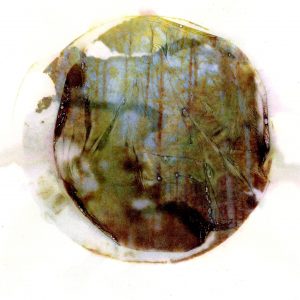

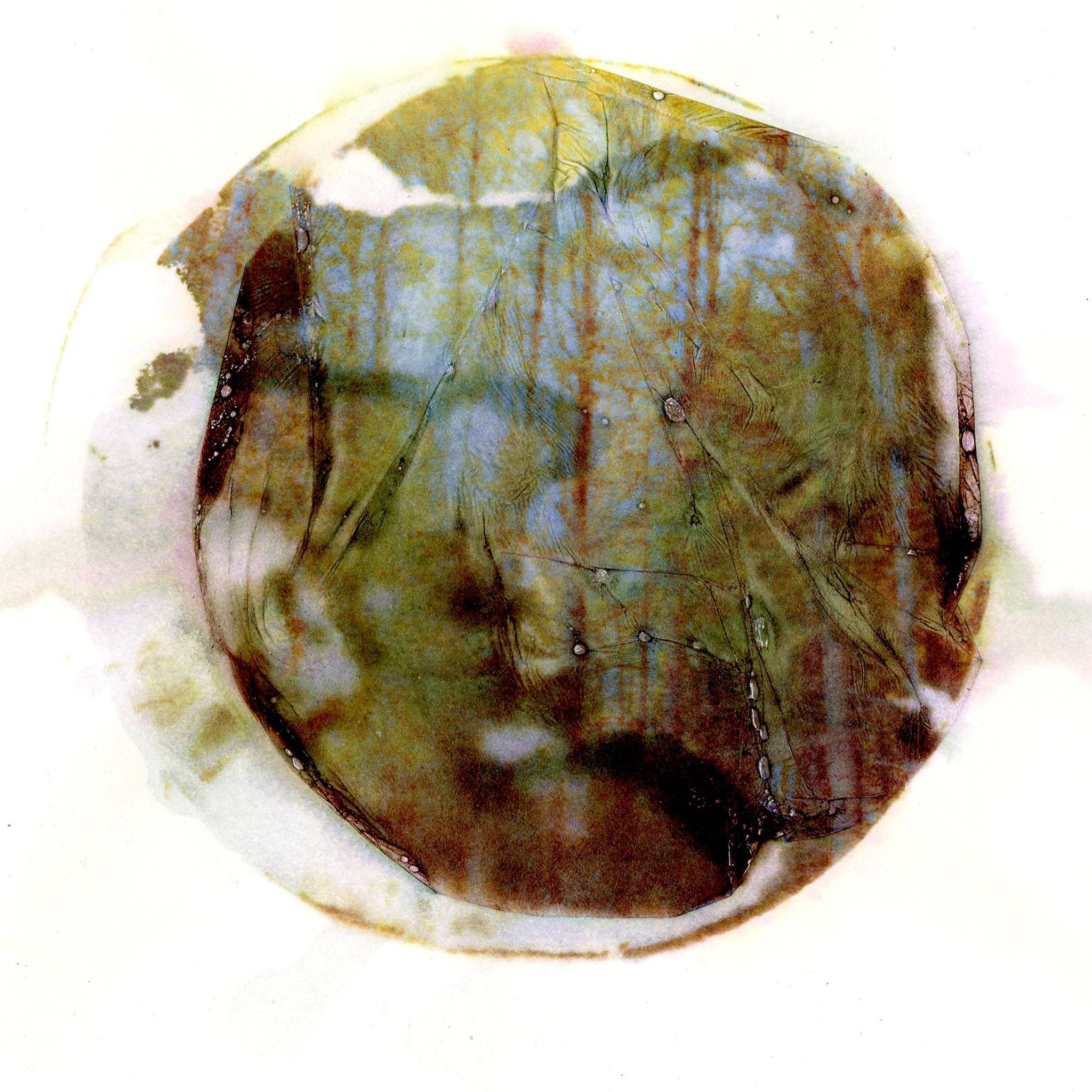

Cree Tylee’s images are conceptual constructions. They tell a story that is, on the one hand, very personal, and yet also have a quality that evokes wider questions about memory – and the mementos that define this intangible experience for us. The colours are sometimes subtle, like watercolours, and other times a void (tinged with a rusty stain), or alternately a splash of vibrancy will hold the eye. The soft, in hue and tone, compositions allude to landscapes, but then one of the series will offer more absence than the layered, composite tones of its fellow works in the series. In one of the later works (At the Beach, 2021, a rectangular scene, unlike the several tondo works, that Tylee simply describes as Portals, but all are water slide prints with ink on paper), figures appear, and offer a bit more of a potentially guided interpretation.

- Untitled, from Portals, 2021

- Untitled, from Portals, 2021

- Untitled, from Portals, 2021

Tylee offers the following about this ongoing project: The initial concept that I’m playing with is interchangeable memories. When talking about the work (specifically to Amy Friend, my teacher and a photographer too) I’ve been referring to these as portals. They’re a combination of photos I took when I went back to the town where I grew up, and also a random assortment of photos that my paternal grandmother took, combined into creating something new, but informed by what they did, and ‘saw.’ It’s interesting to me how I can barely tell the difference between some of them, as the past and the present seem to blend together so seamlessly but then there are also places that are very intangible. But they are portals and this may also have to do with memories, and how I experience these images I’m making from images that my ancestors made, like a form of visual time travel.

It’s worth noting that Amy Friend, whom Tylee refers to as a guide in this work, is an artist whose works also dwell in the spaces of memory, especially images that have been lost and found. This is a useful analogy when looking at Cree’s works: some areas are dense, with overlaid imagery that is challenging to decipher, and other areas are blank, a stark emptiness suggesting gaps in memory or recollection, either personal or due to those moments in many familial narratives, where things are unspoken, unknown, or hidden.

In considering Tylee’s images, it seems odd – but not unfitting – that I find myself revisiting the words of Margaret Laurence, and her writings focused upon female characters who are older, and thus “looking backwards” with both consideration and circumspection. Morag Gunn, in The Diviners, with her Memorybank Movies, bluntly admits that “she was not certain whether the people in the snapshots were legends she had once dreamed only, or were as real as anyone she now knew.” Hagar Shipley, who one might argue lives more in the past than the present through the entirety of The Stone Angel, asserts a disarming – and nostalgia tainted with regret – when she admits “I keep the snapshots not for what they show but for what is hidden in them.” Returning back to Gunn in The Diviners: “I don’t recall when I invented that one. I can remember it, though, very clearly. Looking at the picture and knowing what was hidden in it. I must’ve made it up much later on, long long after something terrible had happened.”

- Untitled, from the series At the Beach, 2021

- Untitled, from Portals, 2021

- Untitled, from the series At the Beach, 2021

I must offer the following disclosure, but in many ways I think it only adds validity to my interpolations of Cree Tylee’s images. Cree and I have known each other for several years, and conversations about her work and my own have often intersected with ideas and experiences of family, memory and community. A previous exhibition at Niagara Artists Centre in downtown St. Catharines that we spoke about featured work by Carrie Perreault (centred on family memories and contested experiences within that circle), in which printed images were then covered completely, thickly redacted, if you will, as that artist’s symbolic manifestation of ‘looking at a picture and knowing’ – or not knowing – ‘what was hidden in it.’ My own photographic work was to be a curatorial project for Tylee, before COVID shifted the world. Our dialogue around that endeavour has offered further nuance to how the idea of places – whether physical or emotional – can be captured in an image, like a personal narrative written in a specific, perhaps deliberately opaque, language.

In Tylee’s images, scenes are presented, but sometimes obscured, sometimes disrupted. Blue skies and trees are suddenly broken by a fold or what seems to be a tear: some lines are clear and ‘in focus’, others bleed together softly, like rust or watercolour, evoking more of a feeling than offering a scene. Several are fragments – like worn papers, weathered and tarnished with age – within the circular composition, offering rich, dense areas suddenly demarcated by an emptiness, a flat absence. “Now I am rampant with memory” laments Hagar Shipley in Laurence’s The Stone Angel: if you’re familiar with the book, that is not a state that Shipley seems to enjoy, nor can she control. Tylee’s images offer insistent fragments (literally, in their evocative, engaging colours and marks) but also elusive ones, hinting more than revealing (as, of course “the occupants of memory have to be protected from strangers”, as Timothy Findley warns us in The Wars).

“As the past moves under your fingers, part of it crumbles. Other parts, you know you’ll never find. This is what you have.” In response to those gaps, Tylee has created something else, in those lovely yet mysterious ‘acts’ of mining memories, both her own and others (such as her grandmother’s, whose photographs collude and combine with Tylee’s Portals), towards what may not be a more ‘accurate’, but perhaps more personally truthful, recollection.

More of Cree Tylee’s art works can be seen here.

Writer

Bart Gazzola is an arts writer, curator and photographer based in Niagara. He’s published with New Art Examiner, Canadian Art, BlackFlash Magazine (where he was editorial chair for three years), Magenta Magazine and Galleries West, and was the art critic at Planet S in Saskatoon for nearly decade. His most recent curatorial project was Welland: Times Present Times Past (2020) at AIH Studios in Welland. He was previously assistant editor at The Sound: Niagara’s Arts and Culture Magazine, where his ongoing series on Brock University and Rodman Hall Art Centre earned him a St. Catharines Arts Award nomination (2020).

~ Posted by Bart Gazzola