Curators' Pick

Diego Rivera | The Detroit Industry Murals (1932 - 1933) - November, 2021

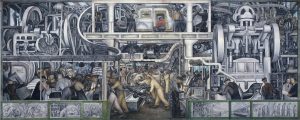

Diego Rivera | The Detroit Industry Murals, 1932 – 1933

Diego Rivera’s work in the Detroit Institute of Arts, titled The Detroit Industry Murals, is one of the finest works of art of the 20th century, and easily one of the finest examples of a mural ever; it’s not inappropriate to appreciate it as the apex of the Mexican artist’s career, and it functions as a significant touchstone of not just the history of Detroit, but of North America and larger issues and ideologies that were dominant at the time of its creation but that still are prevalent now.

“Between 1932 and 1933, Diego Rivera completed this series of twenty-seven fresco panels entitled Detroit Industry on the walls of an inner court at the Detroit Institute of Arts. It was commissioned by capitalist Edsel Ford but conceived by the Marxist artist as a tribute to the city’s industries and labor force. Rivera used the Ford motor plant in Dearborn Michigan as the model for the industry murals. This plant, the Rouge Plant, spread all along the Rouge River, had a steel mill, glass factory, and auto assembly line. By the time Rivera visited these plants, the depression was in full swing but Rivera didn’t record accurately aspects of the Depression. Note, for example the predella panel where workers are lined up to receive their pay in front a parking lot filled with cars, a scene he would not have observed since the work force had been dramatically reduced. In addition to the automobile industry, Rivera chronicles the history and development of various other industries in the area.

- West Wall, 1932 – 33

- South Wall (detail), 1932 – 33

- North Wall (detail), 1932 – 33

At various times the murals have been controversial. Initially, some critics focussed on Rivera’s communism asserting that he had painted a communist manifesto. Others complained that the workers were depicted as dehumanized in the murals, even though most workers saw themselves as represented with dignity. Some complained that the nudes on the East wall were pornographic and saw the “Vaccination” panel as sacrilegious. Later, during the McCarthy era, a large sign was placed in the courtyard with the murals defending the artistic merit of the murals while attacking Rivera’s politics. More recently, a case has been made that the cycle is universal, reflecting “not only the essence of the industrial culture of Detroit but also a belief in technology and science that is operative today. As such, it is a history-making work of art in which the working class and industrialists both find affirmation.” And the aesthetic value of the series is no longer in doubt; many believe that this series of frescoes represent the best of Mexican mural art in the United States.”

This work also has to be seen as part of a larger series, including Rivera’s harsh Frozen Assets (1931 – 32) but also informing Self-Portrait on the Borderline between Mexico and the U.S. (1932) by Frida Kahlo, as they were a duo who contested and completed each other in their painting and ideologies. It’s also good to consider that too often, when engaging with art we privilege interpretations based upon ‘where’ we stand; this work – and the other ones I’ve mentioned by Rivera and Kahlo – looks at the United States with the eyes of an outsider (as I did, too, when I first visited it).

- South Wall, 1932 – 33

- North Wall, 1932 – 33

As a 19 year old new to the city of Detroit (and having my first real experience of the United States), The Detroit Industry Murals awed me (both in seeing the skyscrapers and trappings of the downtown that was the legacy of those glory days, and in stepping outside that bubble to the wasteland and abandoned industrial plants like detritus of a ‘better time’). To stand in the middle of the room, and be enclosed by these works, was a defining experience regarding both the possibilities and responsibilities of art. I’m offering a sampling of images here, but more can be enjoyed at this site: but truthfully, you must see this in person, in the downtown of Detroit, with all of its intersecting and contradicting narratives, and stand it its presence….

More images from this seminal work by Rivera can be seen here (and the long quote in this essay is also taken from there). ~ Bart Gazzola