Eyewitness

From Sam Tata’s Shanghai to Homegrown Terror

And at a certain point, my bureau chief called us into his office. China was finished. Whatever the government did wouldn’t make a difference. The protests would spread across the country, the system would collapse. The tipping point was reached. The cascade was unstoppable. You know what happened next? The Chinese government sent in soldiers and tanks to Tiananmen Square, shot everybody they could. Took the revolution by the neck and crushed the fucking life out of it. Today, China is the most powerful force on the planet, the most powerful force the world has ever known. And it turned out to be the Chinese Century.

Story over. My point? Everything’s containable. But only if you’re willing to do what it takes. I’m willing to do what it takes. Do you believe me? You are a dissident. I am a tank.1

Wallis’ paintings are the product of a kind of obsession, and obsession to recall what he believed to have been real and true about the world of his younger days. He didn’t try to glamorize it or to decorate it with his own fanciful inventions: what his brush recorded was simply ‘what used to be out of my own memory.’ Ben Nicholson, who knew him well, has emphasized that Wallis never considered his paintings as paintings so much as actual events. Each picture was a re-living of some valuable experience and he knew precisely the occasion of that experience and its significance.2

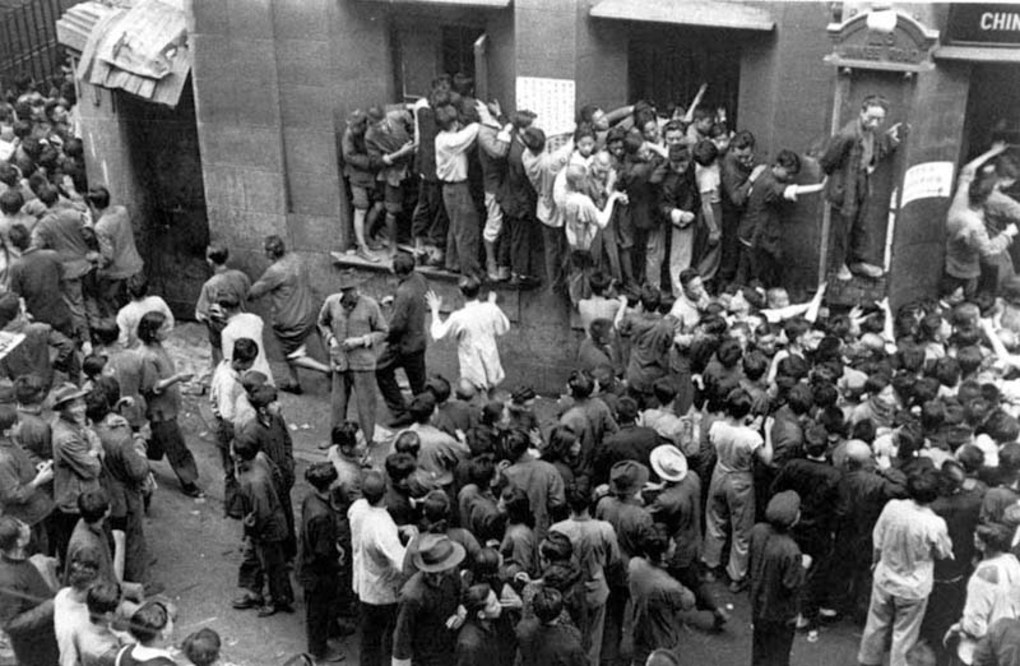

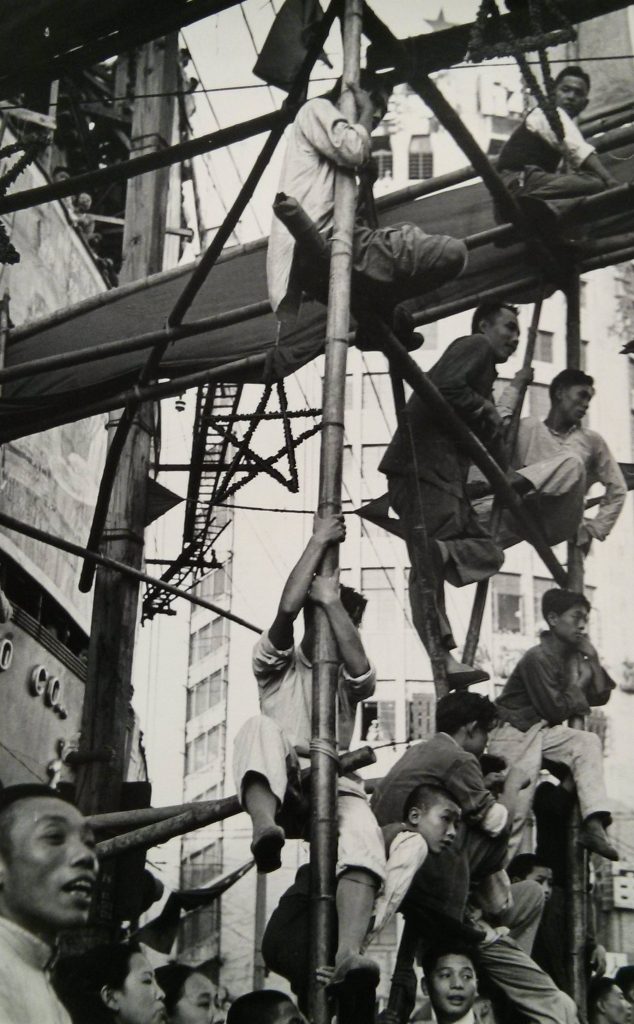

The scenes are alternately banal and confrontational. Several seem almost mundane, chronicling a day perhaps not particularly unique on the streets of Shanghai. However, any student of history in the 20th century will pause upon seeing that they are all from the seminal year of 1949. This was a year when not only China, but the world, shifted, in ways we’re still understanding – or misunderstanding, perhaps, might be a better manner in which to frame this. This is a nod, perhaps, to Zhou Enlai’s intentionally misconstrued response, when asked about the French Revolution of 1789, that it was too soon to judge. In fact, Zhou “was not referring to the 1789 storming of the Bastille in a discussion with Richard Nixon during the late US president’s pioneering China visit. Zhou’s answer related to events only three years earlier – the 1968 students’ riots in Paris, according to Nixon’s interpreter at the time.”3

That contested narrative, those intersecting if oppositional tropes, are something to consider when looking back over seven decades to Sam Tata’s Shanghai 1949 works. That ‘intentional’ misunderstanding is something that has become a false touchstone of history, which is the danger with any photograph, too: Susan Sontag warned us years ago that “[t[o remember is, more and more, not to recall a story but to be able to call up a picture…. Narratives can make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.”4

China Travel Service, early May: crowd milling around, hoping for railway tickets

Tata’s Shanghai images have been in my mind often, of late. When watching the recent terrorist ‘riot’ in the United States capitol, and then “re-watching” it through the almost Biblical flood and ebb of images in social media, or online, the manner in which these two events have been – are being, still, perhaps – negotiated is a place to stand and think about the vagaries of the relationship between history and ‘photography.’ This must also include such things as Instagram, or live streaming, as the bastard children of the black and white photography favoured by Tata, and also for stark contrasts between the observing, separate eye of the journalist and the immediacy, perhaps ‘unmediated’, of the participant in ‘history’.

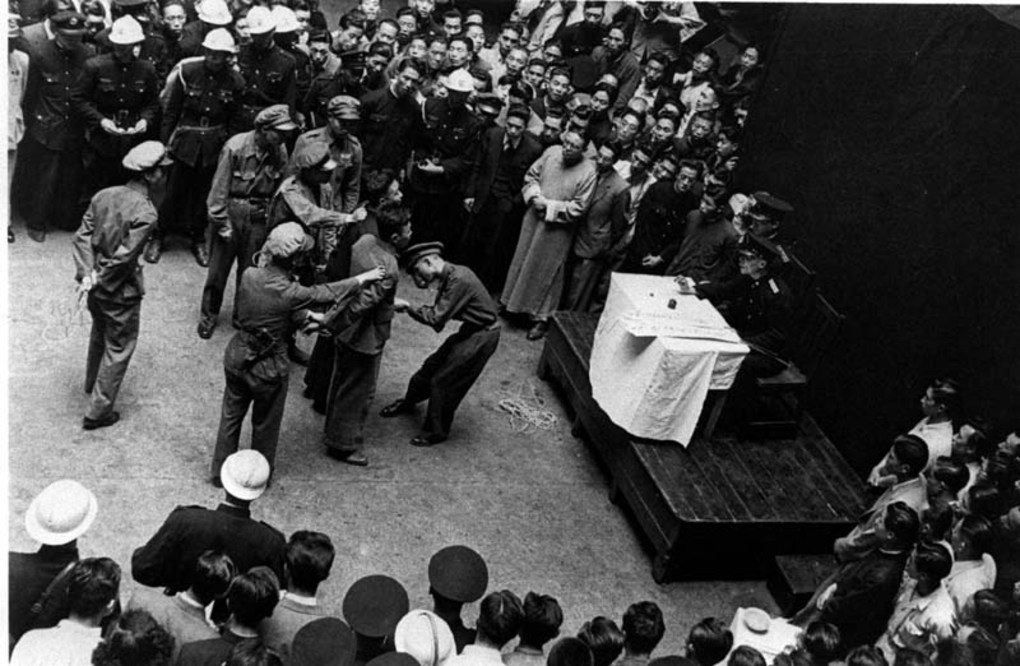

But let’s begin with Sam Tata. This is both to set a standard for formal aesthetics but also as an historical landmark – or harbinger – by which to judge, or understand through similar still moments captured amidst noise and furry, of what happened in Washington, D.C. in early 2021. As I write this, the impeachment ‘trial’ has just come to a close, and comparisons to ‘communist show trials’ are accurate, if not in the manner that many of the right wing terrorists in the United States Senate intended them. The cult of Mao gives way to the cult of Trump: meet the new boss, same as the old boss, or less flippantly, it is (to paraphrase Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta) us, just us, that puts these despots in power….

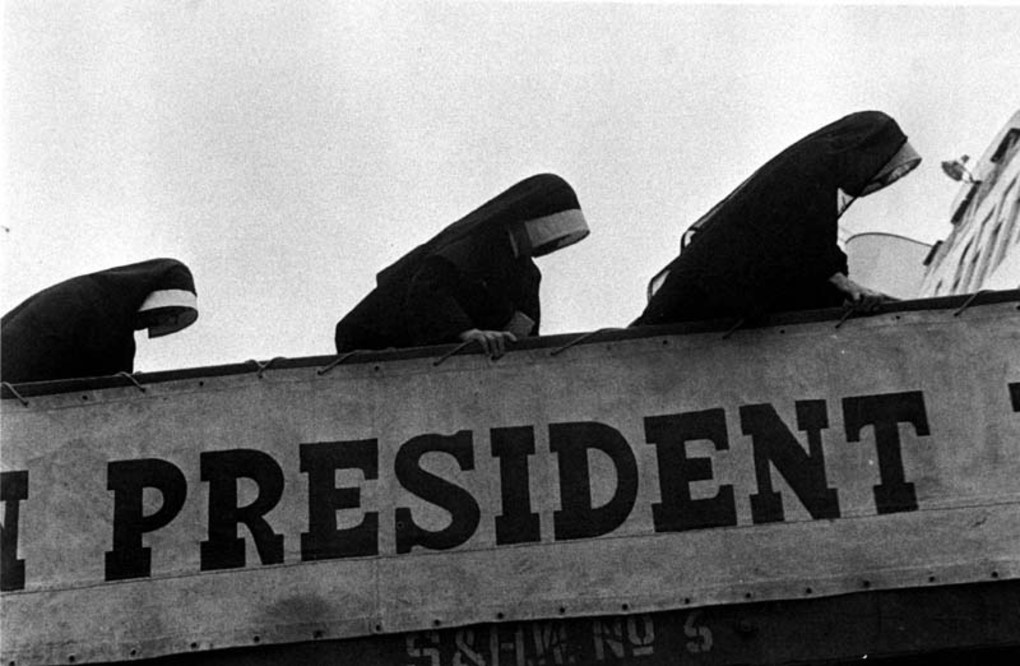

Nuns leaving Shanghai before May from Shanghai & Hongkew Wharf No. 5

As Tata’s images chronicle something that has been forgotten, however, the images in the U.S. Capitol are more so unpleasant reminders of something many are attempting to forget. This may be for ideological reasons (the assertion that American ‘democracy’ is exceptional, and ‘dodged a bullet’, eschewing a necessary prophylactic confrontation with history) or self-serving ones (failed coups, when treated with deference, lead to successful ones. Dwell on the past, lose an eye, but forget the past and lose both eyes, as Solzhenitsyn warned us, if anyone is listening…)

This contrasting correlation continues: Tata’s images require that we seek them out, whereas the glut, the excessive plethora (in quantity and diversity of media) from the 2021 terrorist riot are almost inescapable. This doesn’t preclude many from echoing O’Brien, in Orwell’s 1984, engaging in the syllogism of ‘I don’t remember it’ moments after destroying a newspaper article that directly disproves the party line…. Guy Debord, of the Situationists, would knowingly offer that “the spectacle erases history, turning it into mere images, the significance of which fades.”5 More cynically – or exactly, employ your edits as you will – Sontag warned us that “with time, many staged photographs turn back into historical evidence, albeit of an impure kind— like most historical evidence.”6

Even Jerry Saltz sees this in play, already. His words: “The difference in these new pictures, however, is sadly telling. In fact, we are already seeing that exact perversion of the “meaning” of these images in the herculean effort being made by elected Republican representatives and all of right-wing media to twist these pictures into things that they are not: the regretful expression of only a few, an exercise in free speech. The rioters themselves seem to think that they are the burning girl, the murdered boy, the crying woman. These new pictures are unlike those older pictures in another way too: People are already shrugging them off. The older pictures still burn.” (You can read more of his thoughtful discourse here).

But I’ve digressed there, again, to ‘now’ instead of ‘then.’ Tata’s Shanghai 1949 series is quiet, even if they have a sense of urgency (perhaps more visceral for us now who experience them, knowing what was to come). But Tata’s image of nuns boarding a ship, to flee the impending revolution, is a stark difference to the frenetic fanaticism of those ‘captured’ scaling the walls of the seat of U.S. government. The women’s angular habits against the sky are modernist, taking us away from the event into aesthetics, for a moment.

Tata is someone who might be called a chronologer with his camera, whose works serve as touchstones for landmarks both in Canada and the world. Sometimes this is embodied through the individuals he photographed in his later portraiture but primarily through his work as a journalist, from India to China to various other places.

Sam Tata (September 30, 1911 – July 3, 2005) was described as a Montreal photographer (though he often was away from Canada more often than here), and his impressive resume of photo journalism includes Time Magazine and National Geographic. He was born in Shanghai, which would also be the place where he took some of his most relevant and evocative images.

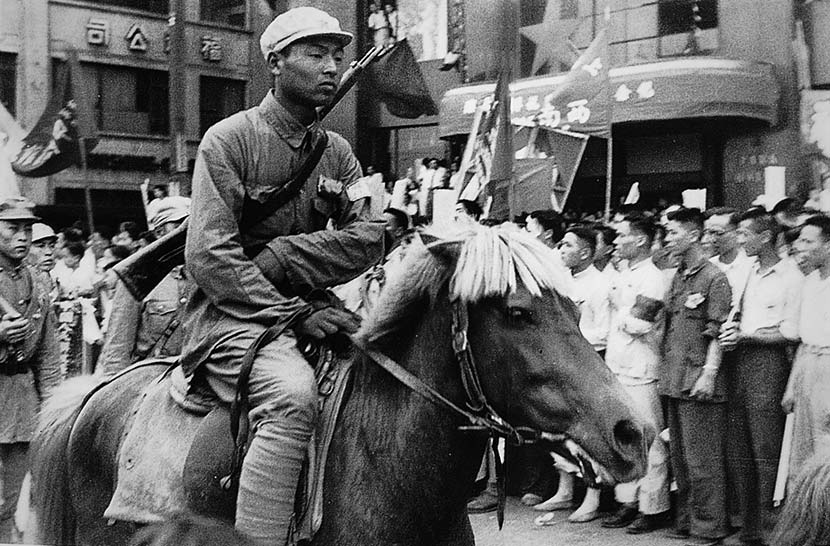

Spectators at Parade by People’s Liberation Army

Tata was greatly influenced by the famous photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom he met in Bombay in 1948. Cartier-Bresson’s genius is evident in Tata’s work, as the former “advised the young photographer to always integrate the environment with people in his photos.”7 The two remained life-long friends. In 1949, Tata photographed events before and after the liberation of Shanghai by the Communists, which led to the establishment of Mao Tse-Tung’s government in China. These documentary photographs of the arrival of Maoist troops and political commissars in that city formed the basis of a book Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era published by Batsford Books in 1989.” (From Virtual Shanghai, which also has a fine interview with Tata)

Tata, rather humbly, asserted the following: “I am not a historian with a camera; merely an observer, and as such was fortunate enough to record fragments of a world shaking event, and great historical change. But perhaps best of all, these records recall to me, with much nostalgia, the streets and alleys of a city I loved, its sights, its sounds and smells, and its memories.”8

Tata, rather humbly, asserted the following: “I am not a historian with a camera; merely an observer, and as such was fortunate enough to record fragments of a world shaking event, and great historical change. But perhaps best of all, these records recall to me, with much nostalgia, the streets and alleys of a city I loved, its sights, its sounds and smells, and its memories.”8

Communist Activists Before A Trial Judge, Shanghai 1949

Many of Tata’s images have a stillness, a stasis. Whether this is due to their being shot in black and white, with all the assumptions regarding ‘the past’ that format encapsulates or to being over a half century old – documenting events at best forgotten, and more likely misunderstood – is an argument to consider. Perhaps it’s also that the banners and names are consigned to ‘history’, and thus thought to be ‘done’, or ‘dead.’ The aforementioned Catholic Nuns Boarding on a Ship, from Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era, 1949 has a quiet tension. Others (such as Communist activists tried by a nationalist military judge, or People’s Liberation Army marching in Liberation Parade in Nanking Road, July) have an historical gravitas. Even the more ‘active’ A crowd parading the portraits of Zhu De, Mao Zedong, Joseph Stalin and Vladimir Lenin is akin to what might illustrate a student’s history text: and no one can look at that picture and not have nostalgia (whether positive or negative), or wondering how many of those marching would survive the Great Leap Forward or the Cultural Revolution. The images are ‘dead’, in more ways than one.

People’s Liberation Army marching in Liberation Parade in Nanking Road, July, 1949

Expanding the trope of death, let’s return to the Capitol riot, and the profusion of documentation (I used that word, though the contested – or dishonest – narratives are already swirling around like flies) around that event. I won’t be sharing any specific images of that, as that seems distasteful: not solely as those scenes are too fresh, too exploitive (like Ai Weiwei’s controversial ‘re imagining’ of drowned three-year-old Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi), but there is an unconscionable pride amongst the terrorists (now being recanted, as consequences come due) that I prefer to avoid. It’s more appropriate to link to this site, which turns these images against them, and in that respect acts more fittingly as an historical record. Those words – ‘history’, ‘record’, again, always – are too often a matter of interpretation and again, Sontag is a useful touchstone here: “This sleight of hand allows photographs to be both objective record and personal testimony, both a faithful copy or transcription of an actual moment of reality and an interpretation of that reality…”9

Propaganda Cartoon showing a PLA soldier about to bayonet Chiang Kai-shek (July 4th Cultural Parade)

The images of Sam Tata and the homegrown terrorists (to cite the previously linked Instagram page) are bookends, or the latest bastardized performance of history as tragedy soon to be farce. The questions that both ‘bodies’ of work raise about photography, the power of the image, history and reality are still with us, and will only continue to proliferate in ways we might expect, or as ‘unknown unknowns’. Tata’s works are not as well-known as merited. Conversely, my decision to decline to share images of the Capitol riot can be construed to be exhausted disgust (a variant on Marshall McLuhan’s warning that excess of images leads to them becoming disposable, forgotten almost immediately after we experience them, as they are simply too much, too often). Images, after all, can’t always be ‘trusted’. The two historical events I’m circling around, overlapping and mixing here, both are ‘defined’ by images “that everyone recognizes are now a constituent part of what a society chooses to think about, or declares that it has chosen to think about. It calls these ideas “memories,” and that is, over the long run, a fiction.”10

North Station, Shanghai, before April: Kuomintang officers with refugees leaving the city for Hangchow

There’s a character in Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride who’s an historian, but also a study herself in the overt and covert ‘constructions’ of history and her discourse[s]. She can write backwards and forwards, and her focus as an historian is encapsulated by her hanging a somewhat famous artwork in her office, with irreverent validity: “On one wall there’s a bad reproduction of Benjamin West’s “The Death of Wolfe,” a lugubrious picture in Tony’s opinion, Wolfe white as a codfish belly, with his eyes rolled piously upwards and many necrophiliac voyeurs in fancy dress grouped around him. Tony keeps it in her office as a reminder, both to herself and to her students, of the vainglory and martyrologizing to which those in her profession [of historians] are occasionally prone.”11

Perhaps, to return to the quote that began this essay, in citing China and Tiananmen Square, that’s what sparked my attempt to scrawl an hereditary relationship between Shanghai 1949 and the scenes from the Capitol riot: one marked the beginning of what is arguably the most powerful nation state the world has ever seen, and one might mark the ending of arguably the first ‘superpower’ nation, ever. Where what happened earlier this year leads ‘us’ is still up for debate – but many who experienced Shanghai as Tata did would not have predicted where we are now, either.

Perhaps, to return to the quote that began this essay, in citing China and Tiananmen Square, that’s what sparked my attempt to scrawl an hereditary relationship between Shanghai 1949 and the scenes from the Capitol riot: one marked the beginning of what is arguably the most powerful nation state the world has ever seen, and one might mark the ending of arguably the first ‘superpower’ nation, ever. Where what happened earlier this year leads ‘us’ is still up for debate – but many who experienced Shanghai as Tata did would not have predicted where we are now, either.

I’ll end with the appropriately circumspect historian that Atwood created for us. I offer her thoughts as a warning, like the previously cited, acerbic Solzhenitsyn: “History is a construct, she tells her students. Any point of entry is possible and all choices are arbitrary. Still, there are definitive moments, moments we use as references, because they break our sense of continuity, they change the direction of time. We can look at these events and we can say that after them things were never the same again. They provide beginnings for us, and endings too….Still, there was once supposed to be a message. Let that be a lesson to you, adults used to say to children, and historians to their readers. But do the stories of history really teach anything at all? In a general sense, thinks Tony, possibly not.”12

July: Liberation Parade in Nanking Row

- Kenton’s monologue, from Alex Garland’s mini series DEVS, 2020

- Edwin Mullins, from the book Alfred Wallis: Cornish Primitive, 2015

- Retrieved from here.

- Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977

- Guy DeBord, The Society of the Spectacle, 1994

- Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977

- From The Tata Era, a retrospective exhibition by the CMCP with accompanying catalogue, published in 1988

- From The Tata Era, a retrospective exhibition by the CMCP with accompanying catalogue, published in 1988

- Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977

- Margaret Atwood, The Robber Bride, 1993

- Margaret Atwood, The Robber Bride, 1993

- Margaret Atwood, The Robber Bride, 1993

Sam Tata’s excellent book Shanghai 1949: The End of an Era, with text by Ian McLachlan, is an excellent resource if you wish to seek out more about this artist. A site I’ve referenced in this article, Virtual Shanghai, is also very informative on Tata’s practice, in China and elsewhere. The majority of images I’ve share here are from their site, and are just a sampling of Tata’s works, in that series (and the header image of this article is Parade with posters of Chuh-Te, Mao, Stalin and Lenin).

As to Capitol Riot / Homegrown Terrorism images, if you have the stomach for an event too recent to be bloodless, I’d direct you to the public presentations for the second impeachment of the former U.S. President.

This article was produced with the support of AIH Studios, where I am often writer / critic in residence, in Welland, ON., and owes part of its genesis to my work on their ongoing Artists You Need To Know series (Sam Tata was a past AYNTK, and you can enjoy that here).

Writer

Bart Gazzola is an arts writer, curator and photographer based in Niagara. He’s published with New Art Examiner, Canadian Art, BlackFlash Magazine (where he was editorial chair for three years), Magenta Magazine and Galleries West, and was the art critic at Planet S in Saskatoon for nearly decade. His most recent curatorial project was Welland: Times Present Times Past (2020) at AIH Studios in Welland. He’s currently assistant editor at The Sound: Niagara’s Arts and Culture Magazine, where his ongoing series on Brock University and Rodman Hall Art Centre earned him a St. Catharines Arts Award nomination (2020).

~ Posted by Bart Gazzola