Weird Baby World

The COVERT Collective is pleased to be participating in Femme Folks Fest 2022. Gabrielle de Montmollin is a well established artist and arts activist who uses humour and surrealism liberally in her projects. Her work currently adorns the historic Carnegie Library on Albert Street in Uptown Waterloo.

“Blessed are those with a voice. If the dolls could speak, no doubt they’d scream, “I didn’t want to become human.”” (Mamoru Oshii, Ghost in the Shell: Innocence)

“…and it feels nothing like a doll. Nothing like a doll at all.” (Neil Gaiman, The Doll’s House)

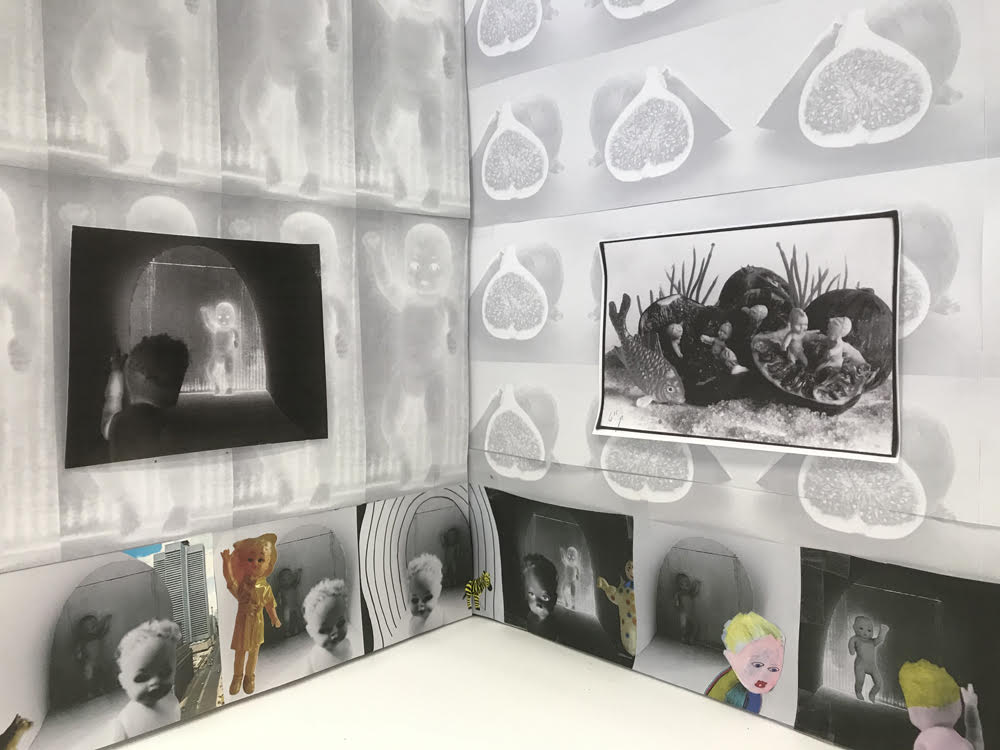

It’s best to encounter Gabrielle de Montmollin’s Weird Baby World at night. In the evening, with St. Paul Street uncharacteristically quiet, the downtown is empty and sparse. The glow from the plate glass window gallery at Niagara Artists Centre (NAC) where Weird Baby World is installed spills out into the street, and the tableaux that Montmollin has assembled for us becomes more ‘alive.’ This is an odd descriptor, I admit, for an artwork that is comprised primarily of images of baby dolls, or toys (sometimes incorporated into the wallpaper backdrops that line the three windows, sometimes as cut out stand alone figures, arranged as though they’ve stepped out of the collaged landscapes behind them. A personal favourite is the perennially diving large fish). But perhaps it’s also appropriate to engage with Weird Baby World in the evening, as there’s a surrealist, dream quality to what is being presented here. As we peer in, through the glass, and the inhabitants of Weird Baby World look back at us (or others ignore us, indifferently), it doesn’t seem quite ‘real.’ It is like peering into another ‘world’, perhaps as opaque and obtuse as dreams often are, that might seem perfectly reasonable until we awake, unsettled and unable to interpret exactly what we’ve just experienced. In William Burroughs’ My Education: A Book of Dreams, which melds a dream diary with other writings, he laments a similar experience: “The dream I am about to relate illustrates the inadequacy of words when there are simply no equivalent meanings. To begin with, it is not a dream in the usual sense, being totally alien to any waking experience. A vision? No, not that either. A visit is the closest I can come. I was there. If I could draw or paint with accuracy, or better still, if I had a camera …”

Montmollin’s statement is direct (and resides in a small case, also outside the gallery, lending even more to a potential interpretation of Weird Baby World as a kind of altarpiece, inviting passing pedestrians to pause and peruse).

Her words: “My art making is based on imagination; I am interested in telling stories, play and mystery.

These are photographs of dolls, they are not real babies. Dolls – the things we give to children to play with. A child playing with a doll attributes a personality to it. A child’s play is often subversive and perverse. I approach dolls in the same way. These images were created from my imagination. In our society these figures are loaded with meaning. Those meanings are always in the back of my mind, but the figures are also personalities who exist primarily as players in the narratives I am exploring.”

Dolls – especially babies – are so rife with interpolations, with a baggage of interpretations of both social and political denotation that any representation of them is not just brimming with charged implications, but overflowing with contested narratives. Montmollin, in conversation, has been quite clear that there’s vagueness about her own interest in this motif; it’s an object, an image, a symbol that fascinates her, but that’s not fixed in its meaning, even for the artist. The idea of dreams, with a nod to surrealism, is one that Montmollin alludes to, as that space allows for – if not encourages – absurdity and alluring perplexity. It also hints at the ‘worlds’ where we sleep and dream, and that we carry those experiences with us as they have a transfixing, staying power.

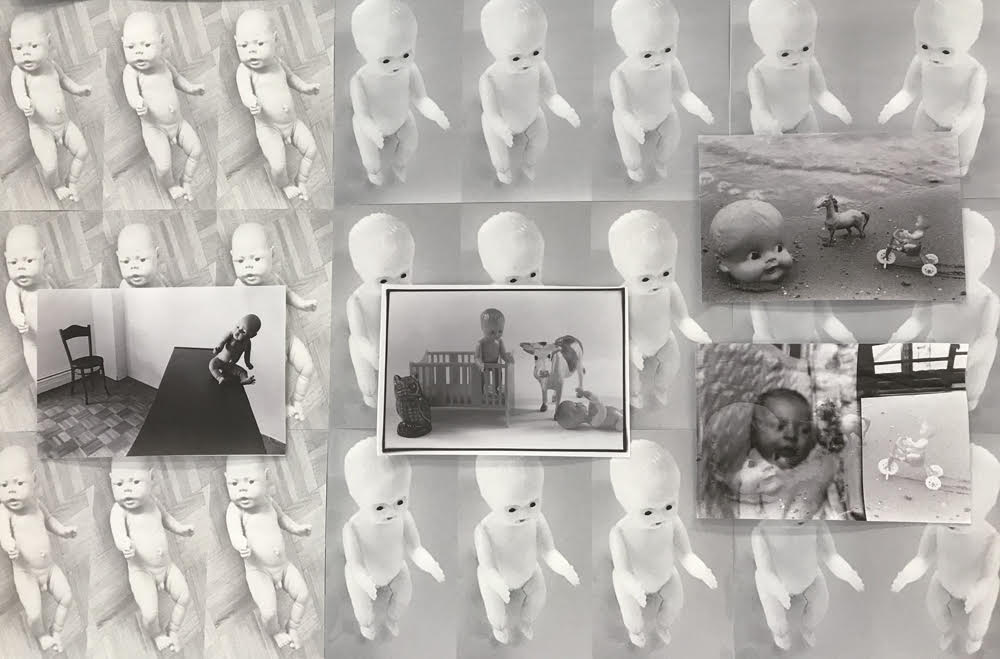

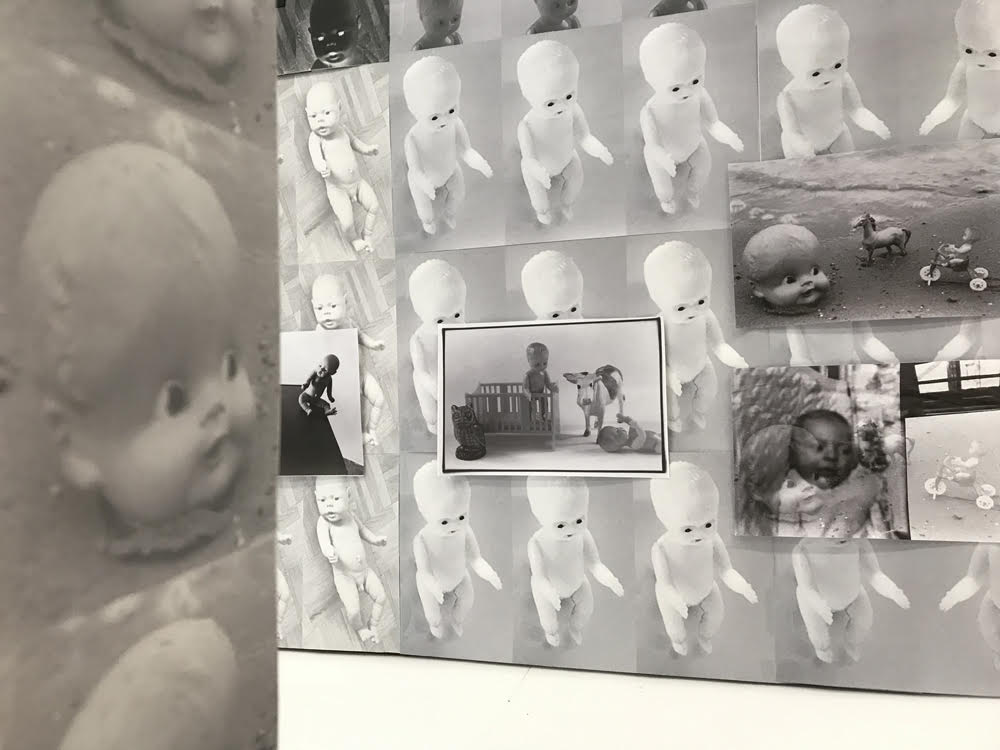

A number of the smaller images that comprise the ‘wallpaper’ of Weird Baby World, or other selected images placed atop this backdrop, depict a number of activities and scenes with the Babies, that sometimes literally play to surrealistic motifs (as in one that appropriates a composition from a Giorgio de Chirico painting), and other times offer scenes eerie yet engaging. Some of the babies recline, on massive eviscerated figs (playing at Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, perhaps, though it’s unclear if they’re eating or about to be eaten); another’s head smiles benignly at us, and their ‘visitors’ at the beach, suggesting both the darker reference of Heston’s iconic moment in Planet of the Apes, or perhaps more so the tranquil if inexplicable narrative of J. G. Ballard’s The Sleeping Giant. In another, a baby – the same anatomically correct model that is literally present in Weird Baby World, sitting, gazing back at us – perches on the edge of a table, surely soon to fall; and an empty chair observes from the left, indifferently (yes, it seems appropriate with Weird Baby World to assign agency and intent to the objects, too – whether the fish or horses, or the Babies themselves….like a dream, anything is possible, if not likely here….)

Many artists have found dolls to be rich reservoirs with a multiplicity of possibilities. The Quay Brothers, for example, have set a standard for objects that – though perhaps ‘cute’, and having a sense of sentimentality – often seem to have a mind of their own, ignoring human projections of rationality, and ignore ‘us’ as we are voyeurs in their world. For example: “The brothers are fascinated by toy stories, and not the cute Pixar kind. It’s as if they raided everything in an attic: their films include grungy, eyeless or limbless puppets as well as dirt, dust, light bulbs, scissors, screws, and string, all of which come alive with stop-motion animation. Their camera — which they consider their third puppet — glides past dolls, contraptions, and machines, leaving just enough time for a glance as these mysterious objects perform ritualized, repetitive gestures and movements.” The actors in Weird Baby World are perhaps the nascent relatives of the players in the Brothers Quay’s Street of Crocodiles, and may yet graduate to that more elaborate surrealist dream within a dream. In writing about an earlier series of images (Not A Child’s World), Montmollin offered that “these figures imply childhood and childish things but through the act of being photographed they lay claim to a world of their own—a whimsical, violent, oddball world which goes beyond imagination and fantasy into the realm where nothing can be taken literally and nothing can be known for certain.”

Some of Montmollin’s insights about dolls are also to be considered here, as you peer into the glassed off, inaccessible Weird Baby World: “I use dolls as stand-ins for real people because of their power of allusion. From the earliest times humans have believed that souls or spirits existed in every object. From this, it was a small jump of intuition to think that if you fashioned a human-like object it could possess the soul of ancestors or beings with supernatural powers who might act on your behalf. The mystical belief in the power of effigies continues to this day. Modern dolls, made of plastic, and manufactured by the millions can cast a similar spell. It is easy to think that they possess lives of their own and are the repositories of unknown consciousness.”

The installation of the work, with three inset spaces broken by the two entrance doors to NAC, also brings to mind a medieval altarpiece, or a theater stage, with a main stage and wings. That a life size, anatomically correct baby doll sits in the centre space only serves this, as ‘he’ holds centre stage, looking less fussy than unimpressed. But the idea of play that Montmollin referenced earlier also intersects with the idea of a play, or roles and performances that are fictions, outside of reality or staid expectations. The babies and animals in Weird Baby World bring to mind the elaborate games of children, so often unclear and indecipherable to ‘adults.’ We can watch, but we’re not invited in, as we not only don’t know the rules, but couldn’t even begin to understand them. Weird Baby World is both a play and play, both an act and a tableaux, and in both considerations ‘plays’ upon the nature of children’s play being incongruous, or outside social conventions. “It should be noted that children at play are not playing about”, observed Montaigne, as early as 1580, but that “their games should be seen as their most serious-minded activity.”

If it seems like I’m not offering any overreaching ‘definition’ of what the inhabitants of Montmollin’s Weird Baby World mean, or what they’re up to, then you’ve been paying attention. To return to an idea from Ghost in the Shell: Innocence (the quote that I began this response to Montmollin’s installation with, and that has been in my mind continuously as I watched the works come together for NAC, is from there), perhaps these Babies, these dolls, have an agency of their own, unanswerable to us. Our projections into the dolls are a violence done to them, privileging our assumed, superior autonomy. We might love our dolls, but they don’t love us back…and do we truly love them, or what we’ve assumed or projected them to be, and what happens (as with Montmollin’s work, or the Quay Brothers) when their actions are unclear, or not easily ‘understood’? And yes, as this essay has progressed, I find myself granting the images and objects that Montmollin has assembled and choreographed an autonomy, an emancipation almost, and thus inhabiting a reality – a world – of their own Weird Baby World.

A final thought, to contest the narrative even more: “In Shinto, everything has a soul. Even if you don’t want the dolls anymore, you can’t abandon them. There is a special ceremony that is performed for them at a shrine. It’s like a ceremony for a dead person. Since dolls have a human form, they must be treated as such.” (Shin Takagi)

Weird Baby World by Gabrielle de Montmollin is on display in the Plate Glass Gallery at Niagara Artists Centre (NAC) right now, and no specific closing date is specified for this work. They’re located at 354 St. Paul Street, in downtown St. Catharines. As Weird Baby World can be enjoyed on the street, hours are not a concern, and I suggest visiting it at various times of day, to ‘watch’ Weird Baby World in different environments and atmospheres. More of Montmollin’s images can be seen here, with several bodies of work that incorporate dolls, in a variety of forms. All images are courtesy the artist: the first set of images are all photos from the maquette of Weird Baby World.

Writer

Bart Gazzola is an arts writer, curator and photographer based in Niagara. He’s published with New Art Examiner, Canadian Art, BlackFlash Magazine (where he was editorial chair for three years), Magenta Magazine and Galleries West, and was the art critic at Planet S in Saskatoon for nearly decade. His most recent curatorial project was Welland: Times Present Times Past (2020) at AIH Studios in Welland. He was previously assistant editor at The Sound: Niagara’s Arts and Culture Magazine, where his ongoing series on Brock University and Rodman Hall Art Centre earned him a St. Catharines Arts Award nomination (2020).

~ Posted by Bart Gazzola