Interview with Julia Huỳnh

by Julie Dring, Guest Curator

In the fall of 2021, I had the opportunity to speak with Julia Huỳnh about a series of photosculptures she made in her earlier years as a photography student at the University of Toronto. Knowing Julia already as an archivist in the greater Toronto area for several years, I was interested to see how she moved to preserving photographic materials as part of her archival work, after years spent destroying their paper form as part of her artistic process. What I learned from Julia is that cutting, crushing, and folding images of you and your family can both be incredibly fun and emotionally tolling. Touching on topics such as the family archive, destruction of the self-portrait, consent and authorship in photography, and more, it was an immense privilege to hear and learn from Julia. I hope you will read her words with the same care she exhibited with each of her responses.

Julie Dring (JD): Your photosculptures were used in several different series in 2013-2014, such as Fit Series, Family Portrait, Inaccessible Image Series, After Series and your Self-Portrait Series. What drew you to displaying the photographic medium in these ways? Is there a reoccurring theme that is portrayed across these series?

Julia Huỳnh (JH): All of these series were created during my undergrad while I was pursuing a studio focus in photography. Through the encouragement of Lise Beaudry as one of my instructors, I really allowed myself to just experiment with different ways of presenting photography whether that be building layers of a photograph, cutting, folding, crumbling, or other ways. I was turning to personal family photographs that I’d had with me since moving and become fond of. I was also working through trying to understand my emotions surrounding my cultural identity. Family Portrait was one of the first of these “photosculptures” where my brother scanned our family portrait for me, and I printed it large enough with the intention to cut it and have it hung from the ceiling. I had no idea how it was going to turn out until I just went for it. This project sparked a lot of interests in wanting to explore the use of private, family photography and displaying them in the public without presenting the full photograph.

JD: How did your Family Portrait Series fit into (or become a launch pad for) other creative projects around a similar theme?

JH: That series along with paintings I had created, were really the beginnings of me trying to understand the nuances of being Vietnamese, Canadian and Vietnamese Canadian. I was using family photographs as references for past painting series and of course, for these photosculptures. This led to my interests in pursing the personal and community archive as well as photography preservation and more specifically, vernacular photographs as they relate to the Vietnamese diaspora. All these interests informed by my art practice, is reflected in my graduate thesis, Performing and Preserving Memories: Vernacular Photographs in the South Vietnamese Diaspora, which explores how photographs from 1980-1995 of the South Vietnamese diasporic community in Orange County, California, communicates selective ideas about exilic identity and function as vehicles for intergenerational transmission of memory.

JD: In your After Series, photosculptures are used to recreate well-known pieces from the cannon of art history. You then somewhat cheekily insert a photograph of yourself into each piece? Can you tell me about what you were thinking when you created this series?

JH: Oh yeah, this series was a lot of fun to create! I remember I had this idea that I wanted to build layers of a photograph using glass that would come together to create an image only when viewed head on. I selected artworks that I studied, and thought would be interesting and fun to try to re-create. I used magazines to create these collages as well as images of myself. Sometimes it’s more obvious whereas in After Velasquez you’ll have to look for a little longer. After Kruger was probably the most unsettling to create to be honest, now that I reflect on it as I deconstructed my own portrait with an exact-o knife to remove my, face, eye, ear and mouth.

JD: I know you as an artist but also as an archivist and photo-preservationist. How have your teachings in preserving photographic objects played into choices you’ve made when selecting photographic materials?

JH: Through my studies, it was and continues to be, frustrating interacting with colonial archives and narratives. I’ve encountered countless violent and colonial images of my community. I often see these historical images and footage shared in documentaries and what not, often without any real care to the people in them or to people viewing them. And despite the plethora of these images, they often render the Vietnamese refugee experience as invisible. I also can’t help but think about the lack of ethics of these records not to mention the violent context and military gazes in which these records were created.

That’s why I gravitate more to the personal and family archive in both my art practice and research to challenge these narratives. In the previous series mentioned, it’s never the original photograph destroyed because I’m not the only person to whom these family photographs belong. As much as I challenged the “preciousness” of family photographs through some of these series, at the end of the day, they’re exactly that. They’re precious artifacts and memories to me.

For a while I’ve been thinking more about co-creation, co-authorship and consent when it comes to the production/ preservation of photographic materials and what that means even for personal records. For instance, I created a short film in 2017 called Chúng Tôi Nhẩy Đầm ở Nhà (We Dance At Home) as part of Reel Asian’s Been Here So Long Program. I weaved my family’s home videos with present-day recordings while interviewing my parents. I last screened the work in my hometown of Nojogiwanong/Peterborough, Ontario at the ReFrame Film Festival in January 2021. I was recently invited to screen the work again, however, I’ve decided not to do so. Even though this film is about my parents and their shifting ideas of home, there are also family friends in these home videos. I’m still trying to understand my role and responsibilities as an artist, archivist, storyteller and member of the community. How can I tell a story without causing harm to others? What if someone doesn’t know they’re becoming a record (someone donates a photograph with them in it, someone takes their image without them knowing etc.)? What if they don’t want to be documented? What if people want to forget? I’ve only just begun to explore some of the questions in rethinking the role of archives through writing. Recently, I wrote an essay exploring this for Archival Affections –a themed commission by Trinity Square Video.

JD: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me, Julia. It was truly a privilege to get to learn more about you and your work, and I look forward to reading your upcoming essay.

Writer

Guest Curator Julie Dring is an Arts Manager working out of Southern Ontario. She has a background in artifact preservation and archives, as well as a passion for cultural work and activism within her community. Her work has allowed her to make both national and international impacts, working at places such as Hamilton Artists Inc., Waterloo Architecture, Forest City Gallery, and the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as researching opportunities throughout the UK. Her research and work has focused on the role of co-operatives and artist-run centres as a place for social change.

Artist

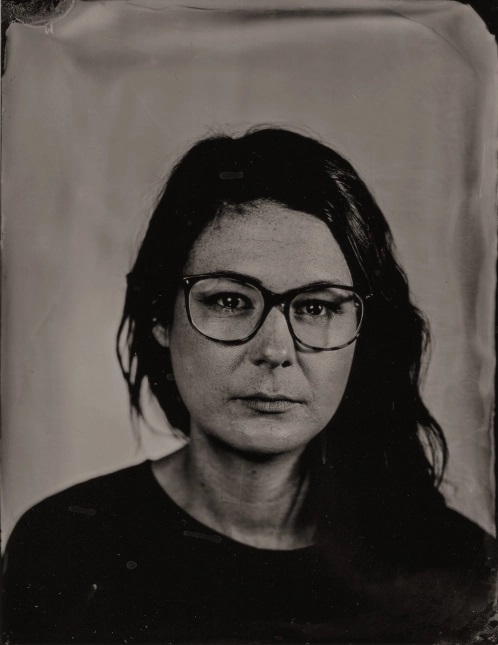

Julia Huỳnh (she/her) is a second generation Vietnamese Canadian interdisciplinary artist, award-winning filmmaker, archivist, researcher and former beauty queen (Miss Viet Nam Toronto 2018).

Through her interdisciplinary art practice, Huỳnh investigates methods of cultural and self preservation, memory, and the constructions of identities and communities in the Vietnamese diaspora. Huỳnh’s research areas of interest include: Vietnamese diaspora visual culture, family photography, social justice in archival studies & library science and oral histories.

Huỳnh graduated with her MA in Photography Preservation and HBA in Art and Art History. She has previous experience working with non-profit organizations, artist-run centres and ethno-specific community-based archives across North America. She’s currently supporting the Photovoice project, “VOICE: Visualizing Our Identities and Cultures for Empowerment” which documents the impact of COVID-19 on the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities in Orange County.

~ Posted by Julie Dring