Curators' Pick

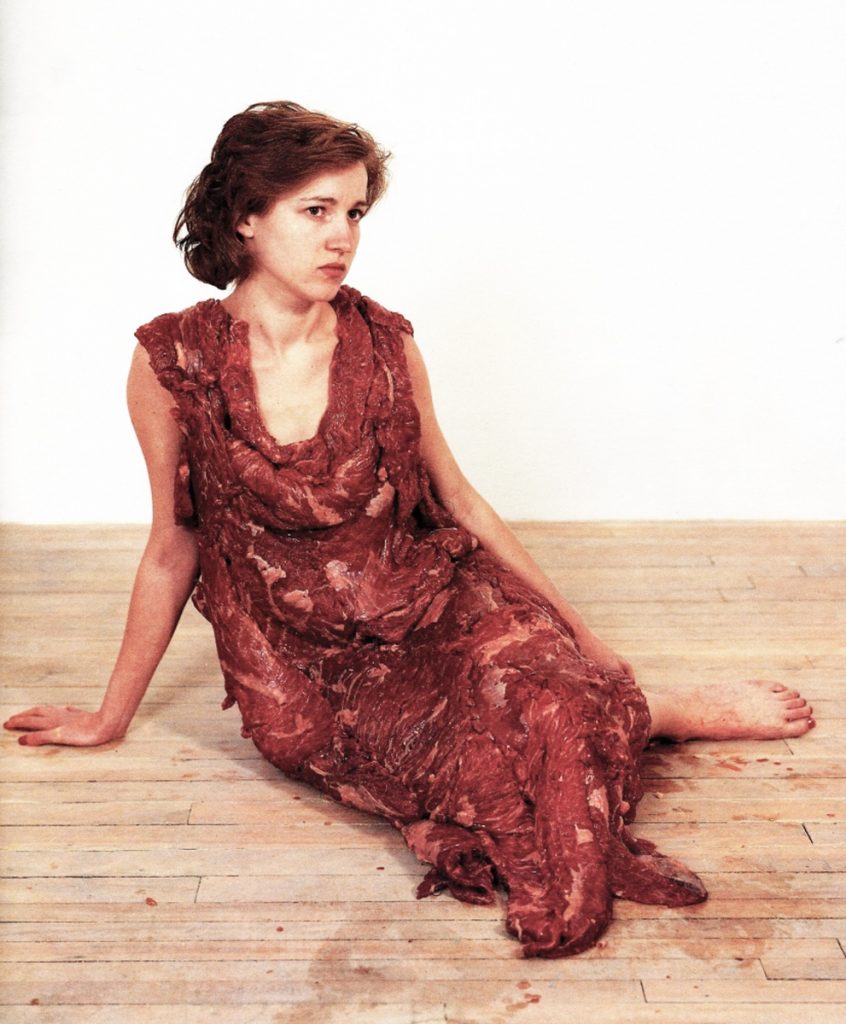

Jana Sterbak | Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic, 1987

Jana Sterbak | Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic, 1987

“Adam was left alone. It was then that God created the Second Wife.”

“Yeah? What was her name?”

“Oh. She never had a name, poor thing. God created her for Adam, out of nothingness. Bones first. Then internal organs. Then flesh. Muscle. Sinew. Fat. Bile. Eyes. Snot. Skin. Hair. Breath…

Adam couldn’t bear to go near her. He wouldn’t touch her.

Bodies are strange. Some people have real problems with the stuff that goes on inside them.”

“Jesus. What happened to her?”

“Opinions differ. Most say God destroyed her. A few have claimed that she was permitted to leave the Garden alone.”

(Neil Gaiman, A Parliament of Rooks)

Ah, the controversy, the pearl clutching, the performative gnashing of teeth: back when this work was installed at the National Gallery of Canada, you would have thought that a Canadian government had wilfully allowed a citizen to be tortured or sent body bags to an Indigenous Reserve as a continuing pattern of colonial violence both literal and ideological. To inject my own time in Saskatchewan, it’s not like Premier who has three DUIs where one led to the death of a young mother, or like Indigenous men are being dumped outside the city, in winter, by police.

In tandem with the hypocrisy around the purchase of Barnett Newman’s Voice of Fire (which has only appreciated with age, unlike the money the taxpayers have paid out in unmerited pensions and perks to the ‘politicians’ who whined about it), it was a strange time for the visual arts in Canada.

But now some facts to balance that vitriolic tangent.

“The artwork consists of a “Flesh Dress”, constructed of slabs of beef sewn together, hung on a tailor’s dummy. It is a one-piece, sleeveless, calf-length “house dress”, with a jagged edge. The marble texture of steak and the thick fat are fully visible, displaying its expressive and bloody appearance. On a nearby wall, a photograph of a young woman poses in the dress. The dress is stitched together from 50–60 pounds of raw flank steak and must be constructed anew each time it is shown. Initially, the steak is fresh and fiery red, and then it gradually turned beige and brown, changing its shape and size to conform to the dummy’s hourglass shape. The work included either $260 or $300 worth of meat, as of its 1991 showing.

As suggested by the title, the work is considered within the genre of “vanitas”, a category of art showing death and decay. The work includes non-traditional materials, a trend in 20th-century art. It “stands in the Surrealist tradition of the uncanny….disturbing the distinctions, by which we categorize experience”.

Progressive Conservative MP Felix Holtmann, a pig farmer from Manitoba commented: “I call it a jerky dress. There are a lot of people who hold food sacred in this land, and they are appalled by the use of food for this thing.” In response, one newspaper editorial called him a “meat head”. Holtmann was chair of the House of Commons Communications and Culture Committee, which oversees the NGC funding; the committee itself was split on the issue. The artist called Holtmann a “self-proclaimed Philistine [who is] not even successful as a hog farmer.” Art critic Christopher Hume commented that the committee’s concept “was based on the notion that the National Gallery is somehow accountable for poverty and hunger in Canada. Surely the irony of their desperate position is that they are members of the group that created the mess the country is now in.””

(All of the above from here).

Sarah Milroy – then writing for Canadian Art, now one of the engines driving the Art Canada Institute – observed that reaction would have been very different if the artist had been male. I’d also inject an observation from Lucy Lippard, when she was writing about the controversies in the United States around the works of Andres Serano, Karen Finley and Robert Mapplethorpe: most – if not all – were driven by those defined – or deformed, if you will – by religion, and thus the body is always ‘bad’ and the only thing worse than that is a woman who makes work about the body. How little has changed, it seems.

But the work itself is at that intersection of horror and aesthetic evocation that we know from art history in the works of Francis Bacon or Francisco Goya. In other ways, this installation by Sterbak can be considered in tandem with Carolyn Wren’s War Map Dress Trilogy, that is a more subtle assertion of Barbara Kruger’s iconic work Untitled (Your body is a battleground).

I feel it’s also important to disclose that while writing this, I was also rewatching Todd Haynes film Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story that “portrays the last 17 years of singer Karen Carpenter’s life, as she struggled with anorexia.” (from here) This is also an artwork that had to deal with the travails of censorship…..

About the artist: “Jana Sterbak forges conceptual, architectonic objects that encourage their wearers to experience bodily and out-of-body freedom. Drawn to notions of doubling, physicality, and self-awareness, she favors juxtapositions between vanity and decomposition as a reminder of human vulnerability. This is evident in her dress of raw meat, which is meant to rest on a hanger until it rots and deteriorates. Such wearable, cage-like constructions allude to technological and societal constraints and a quest for freedom beyond corporeality. Sterbak’s art is marked by a dark humor and absurdist themes likely influenced by her childhood in Prague and education under Marxist and Leninist systems as well as the work of such writers as Franz Kafka and Jaroslav Hasek.” (from here)

More about Sterbak’s life and work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola