Necropolis | Jon Lepp

Necropolis | Jon Lepp, The Open for Business Series

@deadendstories

Photographs, [Virginia] Woolf claims, “are not an argument; they are simply a crude statement of fact addressed to the eye.” The truth is they are not “simply” anything, and certainly not regarded just as facts, by Woolf or anyone else. For, as she immediately adds, “the eye is connected with the brain; the brain with the nervous system. That system sends its messages in a flash through every past memory and present feeling.” This sleight of hand allows photographs to be both objective record and personal testimony, both a faithful copy or transcription of an actual moment of reality and an interpretation of that reality – a feat literature has long aspired to, but could never attain in this literal sense.1

When I was seven or so, riding the bus with my mom, I heard an old geezer rattling on about our city. He had webs of shattered veins in his nose and carried his anger like a pebble in his shoe. Later I’d discover that my city was full of men like him, haunting the Legion Halls and barbershops. I recall what he said verbatim—partly because of the weird mix of venom and resignation in his voice, and partly because of his inventive use of cuss words.

“You want to know how Niagara Falls came to be?” he said. “America swept all its shit north, Canada swept all its shit south, and the dregs of the dregs washed up in a string of diddly-ass border towns, of which Cataract City is undoubtedly the diddliest. Who else takes one of the seven wonders of the world—the numero uno wonder, the Grand Canyon can kiss my pimpled ass—and surrounds it with discount T-shirt shops and goddamn waxwork museums? May as well mount the Hope Diamond in a setting of dog turds. Can’t hack it in Toronto? Come to Cataract City. Can’t hack it in Buffalo? Cataract City’s waiting. Jumped-up Jesus Kee-rist! Can it get much sadder? It’s like finding out you can’t hack it in purgatory and getting your ass shipped straight to hell.”

He’d stared out the bus window, lip curling to touch his nose. “Welcome to hell, suckers.”

I remember, too, how nobody on that bus rose to the city’s defence.2

Perhaps you’re familiar with the short film As Niagara Falls. It can be seen here, and caused quite a controversy when it first went live, online. It’s an interesting short about the two – if not more – realities of the city of Niagara Falls, in Ontario. The political class in Niagara Falls took great umbrage to it (failing, of course, to see that this offense proved some of the points offered in the film). The mayor of the city – same then as now – is not without his own controversies and is as vilified as he is (perhaps) lauded, even before COVID fell upon us, and larger issues of the market and tourism, which defines that place, became even more problematic. It may have been a ‘burn the messenger while ignoring the message’ moment….

As Niagara Falls was in my mind as I watched Jon Lepp’s series of images progress and accumulate online, where he posted them on a regular basis, and is now in the process of forming them into a book. His scenes, from The Open for Business Series are both stark and evocative. More specific to the locales that Lepp captures, I found myself rereading Craig Davidson’s excellent book Cataract City – a colloquial if contemptuous name for Niagara Falls, which offers a fine literary correlation to the images that Lepp offers. Interestingly, Lepp hasn’t read the book, though the veracity of both of their visions of that city overlap, if not intersect. I feel compelled to quote Cataract City liberally in this essay, especially in this instance where a character is remembering some indignity of failed infrastructure: Nobody bothered petitioning the city hall about it: to live in Cataract City was to accept many disappointments.

We grew up in Niagara Falls, also known as Cataract City—a nickname based on the Latin word for waterfall, I learned in class. But my mother, a nurse, said there was an above-average rate of actual cataracts in the city, the eye kind, which often led to glaucoma.3 (A somewhat irreverent instance of ‘speaking in collage’ with this essay that I could not resist here, even if in terms of responding to photographic works…but I’m not referring to Lepp’s vision, but that of others that he’s recorded here).

As a kid, I found it tough to get a grip on my hometown’s place in the world…I figured most places must be a lot like where I lived: dominated by rowhouses with tarpaper roofs, squat apartment blocks painted the colour of boiled meat, rusted playgrounds, butcher shops and cramped corner stores where you could buy loose cigarettes for a dime apiece.4

Lepp’s work acts as a document of a very specific region, but also of a very specific state of affairs, with closures and quarantines. Like a portrait of a person, his images are rife with the specificity of that time and intersection of events and experiences, and cannot be fully understood without a consideration of that. The title is alternately sardonic and aggressive (can anyone hear this phrase now, and not think of politicians and their glad handers jibbering about being ‘open for business’, in the ‘post’ COVID era?). But it also functions on multiple levels of interpretation, as many of Lepp’s images are portraits of Niagara Falls, and other stricken rust belt wonderlands of the Niagara Region, that are in the bust of a boom and bust cycle, perhaps. So, when seeing images of the Falls, a deeper reading would bring to mind how the political class of the city has hitched its star to tourism, with its various vagaries of supply and demand, and the fractures in between that real people and communities fall through….

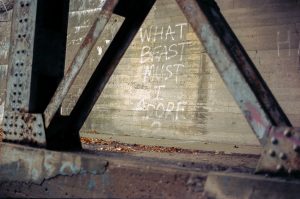

Niagara Falls is nothing if not a contested narrative made physical, in concrete and neon and crumbling structures. Empty houses have this look to them, or at least they do in Cataract City: like faces ravaged by leprosy. Shattered bay windows resemble leering mouths; punched-out second-storey windows look like avulsed eyeballs. Darkness had a way of transforming everyday sights into nightmarish apparitions.5

It’s like Las Vegas, or even Detroit – the imaginary ‘version’ of the site is more real, to many, than the actual place itself (this applies well to the message of As Niagara Falls). Lepp wandered around Niagara Falls – and other areas in the Niagara Region, but the Falls is both the most represented in this collection, and most often those images encapsulate Lepp’s ideas and aesthetic – and his simple, straightforward documentation of that city during COVID, when a lockdown had turned the tourist mecca into all but a ghost town are very much of the ‘real’, not the imagined.

While working on this, I saw an Instagram post about a ‘graveyard’ of old Big Boy Restaurant statues, which used to adorn their outlets but are now discarded. Growing up in Niagara, Big Boy was a thriving enterprise (my wastrel of a brother was employed there, which meant it was an opportune space for even the most lacking), and there’s something about this that connects to Lepp’s images of shuttered spaces and ramshackle buildings. Perhaps ‘we’ are open for business but with nothing to purchase, and without the means to purchase, anyway. COVID has shown that the ‘freedom’ to do business is even more paramount than before, in this epoch of late capitalist modernism, and Ontario’s Premier and Niagara Falls’ Mayor are charlatans, even snake oil salesmen, looking back at lost ‘glories’ and spouting slogans that ring hollow when looking at the ruins that Lepp has photographed, here.

Lepp is a musician and a writer, and in conversation, he commented that his work in those media is more celebratory of the region (perhaps as that offers space for more interpretation, without the albatross that photography has around its neck of being ‘real’). We spoke of how during one of the lockdowns he visited Niagara Falls almost daily and that the forsaken spaces and desolation also reminded him of the high turnover there, of both businesses and staff. Despite the quiet atmosphere, construction was still ongoing, like a false pretense of prosperity, a fake proactivity. Having lived in other cities in Canada where construction ‘boomed’ yet nothing else thrived, and other spaces atrophied, this was not an unfamiliar story.

As stated above, these pictures are less performative than his work in other media, being more ‘authentic’ as solitary acts of documentation of immediate experience. Lepp is influenced by the work of Kyle McDougall – and I should add that when Lepp and I spoke, the Niagara works of Alec Soth also came up in conversation. Another artist whose aesthetic intersects with Lepp’s can also be found on Instagram: The Great Texas Road Story. The bleached colours, the dilapidated tableaux that look like they’ve been washed out under the harsh weather of a dustbowl environment have a resonance with Lepp’s images of economic hardship. In this same vein, the IG of Jack Germsheid, evocatively titled Motel of Lost Companions, shares similar ideas with Lepp’s work.

Lepp’s images have a grittiness – not just in terms of subject matter, but the film he shoots has a grainy, textural quality – and many of his scenes seem somewhat blanched, greying as though they’ve dissipated – or been leeched of their vibrancy. Then, when perusing Lepp’s further in his Open for Business series, a mise-en-scène of some tourist attraction that’s bright and striking seems almost too garish, too much, like it’s been offered as an artificial stimulant to the barrenness of the other – more veritable – environs.

These days I drive the city sometimes, alone at night. I drive past the places that built me, remembering….Those places created me. Time shifts and passes more quickly now, and I sense things will never seem as real as they did in those days. Still, there’s a vital current that runs through the heart of Cataract City, too. That current twists and bends and flows into still pools from which there is no exit. And there is a shadow side to that current, an undertow that flows towards the Falls. In it you can see things toiling, things shifting. And there are always hands to beckon you over.6

Jon Lepp’s The Open For Business series is a visual statement about the city of Niagara Falls: he offers a disparate yet overlapping, if not intersecting series of ‘portraits’, often in opposition to more official narratives of a city that exists, arguably, more in imaginations than in humble stone and steel.

This essay, about his work, is titled Necropolis as when I experienced Lepp’s visual essay – and when I’ve walked these same streets he did – another writer’s words filled my mind : Such are my pictures of the dead.7

Endnotes

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 2003

- Craig Davidson, Cataract City, 2013

- Craig Davidson, Cataract City, 2013

- Craig Davidson, Cataract City, 2013

- Craig Davidson, Cataract City, 2013

- Craig Davidson, Cataract City, 2013

- Margaret Atwood, Cat’s Eye, 1988

Artist

Jon Lepp is a multidisciplinary artist from St. Catharines, ON. Whether through photography, filmmaking, songwriting or poetry, he is constantly finding new ways to share stories. His photo series, Open for Business, documents Niagara Falls and the surrounding areas during the Covid-19 pandemic. As a commercial photographer, he focuses primarily on portraiture and events. His collection of poetry, Hopping On, was shortlisted for the 2016 “Wanted Works Contest” through Grey Borders Books and his poetry has been published in journals in Canada, New Zealand and Nigeria. His debut album, Taking My Way, was released in 2019 which saw him tour Canada and the UK.

Lepp works in a variety of media, and you can enjoy that at the links below.

~ Posted by Bart Gazzola