In: Chinese art

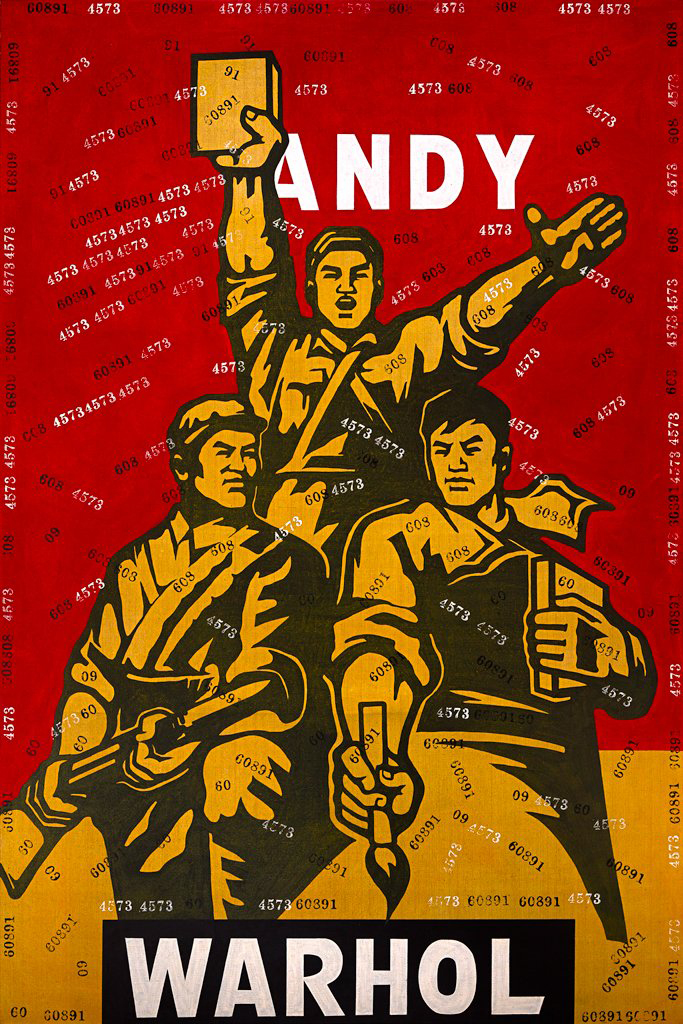

Great Criticism Series: Andy Warhol, 2001 | Wang Guangyi 王广义

April 7, 2022Great Criticism Series: Andy Warhol, 2001 | Wang Guangyi 王广义

A few years ago I re-read George Orwell’s All Art Is Propaganda. Orwell is a hot topic these days, too often cited by those who haven’t read him and barely – or refuse to actually – understand the points he was making. Here in Niagara, a mayor responded to an appropriate censure – and consequences – for his dishonesty and religious gibberish by misquoting Orwell, and his smug ignorance was more akin to what Orwell opposed, and criticized, than what the author supported.

Propaganda is perhaps most dangerous not when we can recognize it, but when it has become ubiquitous – and this is on my mind when encountering the works of Chinese artist Wang Guangyi (王广义), who (in that often sloppy way that art historians and critics try to slap a label on something, dismissing nuance and dissent) has been described as a Chinese Political Pop Artist.

There is much more at play here than that: “I came to realize that the essence of art is its ancestry, its history,” the artist has said. “When creating a work of art, one’s head is full of these historical considerations; an encounter with what has been and its entry into the process of rectification.”

“Great Criticism is Wang Guangyi’s most famous cycle of works. These works use propaganda images of the Cultural Revolution and contemporary logos from Western advertisements. Wang Guangyi began this cycle in 1990 and ended it in 2007 when he became convinced that its international success would compromise the original meaning of the works, namely that political and commercial propaganda are two forms of brainwashing.”

An interesting and subtle allusion to the vagaries of propaganda and control are in the ‘two repeating, randomly selected numbers [that] can be found stamped across the composition. During the Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976), two licenses were required for the production of any image for public consumption: one to produce the image, and another to distribute it. These numbers then reference the extreme restrictions on creative production during Wang’s formative years.” (from here)

Slavoj Žižek has asserted (or warned, edit as you will) that we can imagine the end of the world more easily than we can imagine the end of capitalism. Another intersecting trope – and why I chose this work, of his many fine pieces in this series, that lumps in the idea that is ‘Warhol’ with other capitalist monoliths like McDonalds, Disney or Pepsi – is the rise of the NFT in the larger art world, where money not only ‘creates’ taste, but invalidates any other dissenting concerns. Or, as Warhol warned us, Art is what you can get away with…just like propaganda.

Wang Guangyi (王广义)’s site is here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

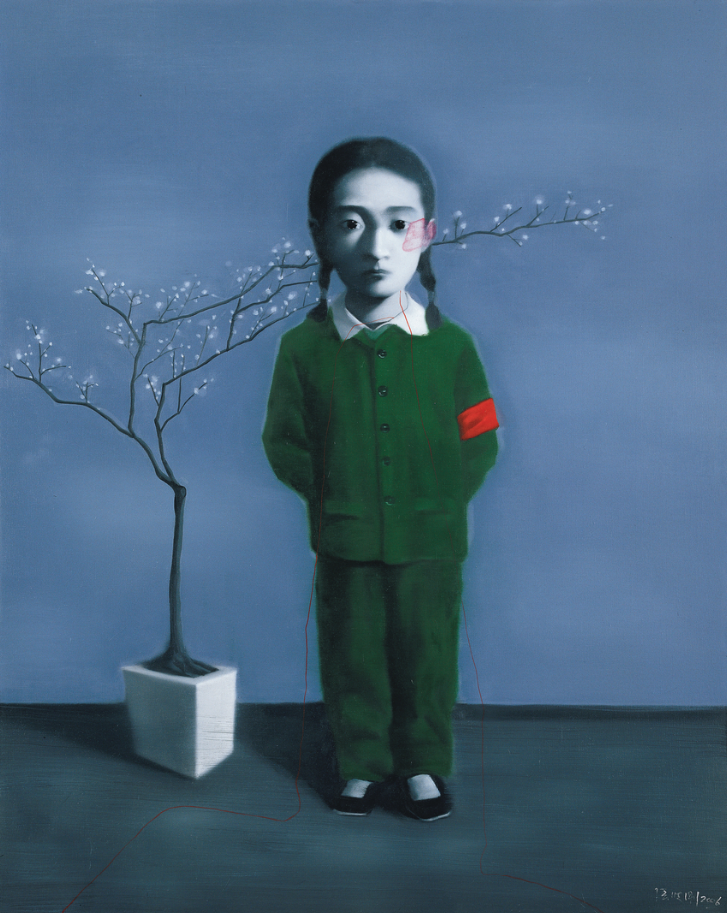

Zhang Xiaogang | Girl and Tree, 2007 – 2008 – December, 2021

December 29, 2021Zhang Xiaogang | Girl and Tree, 2007 – 2008

Several years ago, a friend suggested Jan Wong’s book Red China Blues: My Long March From Mao to Now to me. It was a memoir that touched upon major historical events, but always with a personal stance of Wong’s experiences as both the child of Chinese immigrants to Canada, but also as a person who, as a teenager in the late 1960s, was enamoured of Mao Tse Tung, and lived for some time in China during the Cultural Revolution. Years later – as chronicled in the book – she would be in Beijing when the Tiannamen Square Massacre happened. It’s a good book: Wong is a meticulous narrator, and spares neither her young self, nor larger mythologies of the State (whether China or Canada) from an older, wiser voice of criticism.

When I first encountered the work of Zhang Xiaogang, Wong’s stories of the Cultural Revolution (which she was protected from, being a Canadian still too anaesthetized by ideology over reality) immediately came to mind. Zhang’s figures are grim: they also make me recall a ‘joke’ from another friend, whose family fled communist Poland, about ‘Soviet photo face.’ This is the idea – which any cursory review of official photography from the USSR, or any totalitarian state, really, will reveal – that you must offer a facial expression, in all images, that is neutral, lest it be used against you later, and you find yourself in the gulag or a re education camp.

“Inspired by contemporary tensions in China, Zhang Xiaogang makes grim, unsettling portraits that consider identity and heredity in a collectivist state. The artist draws on influences that include political iconography, Chinese charcoal drawings, distorted Surrealist compositions, and family portraits from the Cultural Revolution era. His paintings, often executed in grisaille with bursts of bright yellow or red at the center, explore how varied individual histories are flattened into conformist representations.” (from here, where you can enjoy more of Zhang Xiaogang’s artwork) ~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments