In: Chinese Political Art

A – MAZE – ING LAUGHTER, 2009 | YUE MINJUN

July 28, 2022A – Maze – ing Laughter, 2009 | Yue Minjun 岳敏君

A bronze sculpture located in Morton Park in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

I NEVER knew anyone so keenly alive to a joke as the king was. He seemed to live only for joking. To tell a good story of the joke kind, and to tell it well, was the surest road to his favor. Thus it happened that his seven ministers were all noted for their accomplishments as jokers. They all took after the king, too, in being large, corpulent, oily men, as well as inimitable jokers.

(Edgar Allan Poe, Hop-Frog; Or, the Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs, 1849)

Art in the public sphere is often interesting: the intended meaning of the artist may be subsumed by the larger interpellation of the work by the publics or communities that interact with the artwork on a daily basis, or over extended periods of time. You don’t even need to consider the larger argument about monuments that proffer ideologies that were once celebrated and are now suspect (to say the least): Yue Minjun’s installation in Morton Park, in Vancouver, B.C., can’t help but have an unsettling quality, and critical analysis of his work has used the phrase ‘cynical realism’ repeatedly, though the artist seems somewhat neutral on that categorization….

Minjun’s larger than life characters are surely laughing at us, not with us – and their number, their intimidating nature, their grins and smiles that seem ready to eat us up, brought to mind Edgar Allan Poe’s dark story Hop – Frog (specifically the king and his ministers, with their ‘jocular’ abuses of those weaker than they) which I quoted at the beginning of this curator’s pick.

I do favour literary references when responding to visual arts, but this one is particularly apt. The synopsis of the story: The title character, a person with dwarfism taken from his homeland, becomes the jester of a king particularly fond of practical jokes. Taking revenge on the king and his cabinet for the king’s striking of his friend and fellow dwarf Trippetta, he dresses the king and his cabinet as orangutans for a masquerade. In front of the king’s guests, Hop-Frog murders them all by setting their costumes on fire before escaping with Trippetta. (from here)

But that description is a bit bloodless: Poe was erudite, especially in terms of more morbid, or caustic, turns of phrase, and his characters reflected this.

Hop Frog’s final declaration, in the story, and his last words before escaping, are these:

“Ah, ha!” said at length the infuriated jester. “Ah, ha! I begin to see who these people are now!” Here, pretending to scrutinize the king more closely, he held the flambeau to the flaxen coat which enveloped him, and which instantly burst into a sheet of vivid flame. In less than half a minute the whole eight ourang-outangs were blazing fiercely, amid the shrieks of the multitude who gazed at them from below, horror-stricken, and without the power to render them the slightest assistance.

At length the flames, suddenly increasing in virulence, forced the jester to climb higher up the chain, to be out of their reach; and, as he made this movement, the crowd again sank, for a brief instant, into silence. The dwarf seized his opportunity, and once more spoke:

“I now see distinctly.” he said, “what manner of people these maskers are. They are a great king and his seven privy-councillors, — a king who does not scruple to strike a defenceless girl and his seven councillors who abet him in the outrage. As for myself, I am simply Hop-Frog, the jester — and this is my last jest.”

Perhaps that scenario that Poe wrote – where those who mock are held to account – is a good one, to keep in mind as you wander the maze of these towering, awing figures that seem to cow us with their dramatic poses. But it would be remiss to not consider a less dour reading, which coincides with what brought these works to my attention – and that is from a recent rewatch I engaged in, focused on the iconic television series The X-Files.

To steal another’s words on this: Maybe the problem is that we’re confusing the mirror for the window and vice-versa. The fact that Mulder and Dr. They are discussing these provocative ideas among the fourteen statues that make up the “A-maze-ing Laughter” exhibit in Vancouver’s Morton Park adds another complicating layer. These bronze behemoths, each in a petrified state of hysterics, were conceived by the Beijing-based artist Yue Minjun as exaggerated self-portraits, and fall under the movement known as Cynical Realism, a response to the Chinese government’s oppressive approaches to aesthetic expression. Yet they’ve paradoxically brought such joy to a populace an ocean away that they’ve been made a permanent fixture of the Vancouver cityscape….Pain in one place begets gaiety in another, and even a calcified smile has the power to counteract, if not necessarily defeat, the despots. (from here)

All images are from Wikipedia Commons.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

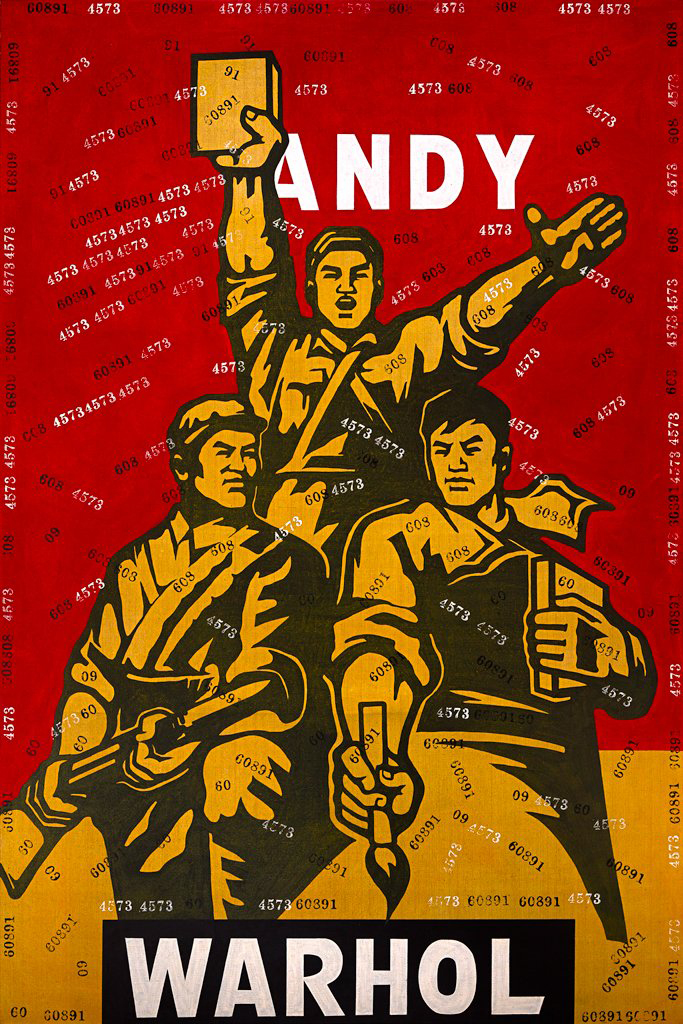

Great Criticism Series: Andy Warhol, 2001 | Wang Guangyi 王广义

April 7, 2022Great Criticism Series: Andy Warhol, 2001 | Wang Guangyi 王广义

A few years ago I re-read George Orwell’s All Art Is Propaganda. Orwell is a hot topic these days, too often cited by those who haven’t read him and barely – or refuse to actually – understand the points he was making. Here in Niagara, a mayor responded to an appropriate censure – and consequences – for his dishonesty and religious gibberish by misquoting Orwell, and his smug ignorance was more akin to what Orwell opposed, and criticized, than what the author supported.

Propaganda is perhaps most dangerous not when we can recognize it, but when it has become ubiquitous – and this is on my mind when encountering the works of Chinese artist Wang Guangyi (王广义), who (in that often sloppy way that art historians and critics try to slap a label on something, dismissing nuance and dissent) has been described as a Chinese Political Pop Artist.

There is much more at play here than that: “I came to realize that the essence of art is its ancestry, its history,” the artist has said. “When creating a work of art, one’s head is full of these historical considerations; an encounter with what has been and its entry into the process of rectification.”

“Great Criticism is Wang Guangyi’s most famous cycle of works. These works use propaganda images of the Cultural Revolution and contemporary logos from Western advertisements. Wang Guangyi began this cycle in 1990 and ended it in 2007 when he became convinced that its international success would compromise the original meaning of the works, namely that political and commercial propaganda are two forms of brainwashing.”

An interesting and subtle allusion to the vagaries of propaganda and control are in the ‘two repeating, randomly selected numbers [that] can be found stamped across the composition. During the Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976), two licenses were required for the production of any image for public consumption: one to produce the image, and another to distribute it. These numbers then reference the extreme restrictions on creative production during Wang’s formative years.” (from here)

Slavoj Žižek has asserted (or warned, edit as you will) that we can imagine the end of the world more easily than we can imagine the end of capitalism. Another intersecting trope – and why I chose this work, of his many fine pieces in this series, that lumps in the idea that is ‘Warhol’ with other capitalist monoliths like McDonalds, Disney or Pepsi – is the rise of the NFT in the larger art world, where money not only ‘creates’ taste, but invalidates any other dissenting concerns. Or, as Warhol warned us, Art is what you can get away with…just like propaganda.

Wang Guangyi (王广义)’s site is here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments