In: russian art

Katerina Belkina | The Dinner, 2016

February 15, 2024Katerina Belkina | The Dinner, 2016 (from the series Repast)

(Photography, Digital Painting)

“God sendeth and giveth both mouth and the meat.”

(Thomas Tusser, 1524 – 1580)

I will admit that there are certain fascinations (or perhaps less charitably or more directly classified) obsessions that ‘feed’ my interests in terms of artworks.

Meat – and how many artists employ flesh as inspiration or subject – is one of them. I offered a previous essay (centered on the fine paintings of Scott Conary) that explored this, but when I was making artworks prior to my exile or migration to Niagara (edit as you will) I often worked with fat, meat, bones and other organic matter, to make works that I described as ‘inappropriately beautiful.’

Sometimes, amidst the cacophony – or idiot choir – of ‘art criticism’ these days, with references pedantic and claiming to be ‘philosophical’ it is good to return to simply a notion of beauty. One of my best teachers, Patrick Traer – a fine artist whose work dealt with these contested, perhaps conflicting, narratives – spoke of this to me years ago, when I was still on the Prairies.

Belkina’s artwork that I share here is gripping, and perhaps inappropriately (to some weaker constitutions) beautiful. She offers some interesting ideas about her motivation and ideas that sometimes intersect with my own subjectivity, but this is an image that is striking and that, frankly, is enough.

Her religious connections are not of particular interest to me : but I must admit that my own religious upbringing (or indoctrination) have sometimes directed my interests, too – and there is a fecundity of potential interpretations that contest or converge that make her work worthy of consideration, whatever your pre existing assumptions (and I include myself in this statement).

From her site :

“Repast is an allegory of life cycles. Cyclicity perfectly characterizes humanity and our perception of time.

The Morning (childhood) means acquisition and accumulation. At the beginning of life we receive a certain foundation and potency both from our family and from the society in which we live. We learn to recognize the beauty around us and to feel it — we use all this for the rest of our lives. Even if “breakfast” is sparse in physical reality, it is often filled to the brim with intangible treasures such as love, fantasy, discoveries, strong impressions and first disappointments. In “breakfast” the abundance of dairy products is symbolic. The milk is associated with purity and virginity. The memories of breast milk are still fresh. The fullness you see is an exaggeration. The yellow of orange juice symbolizes concentrated emotions, the taste of life, sincere joy, and the energy of children. A lemon or an orange signifies the unquenchable thirst for action, knowledge, and discovery.

The Day (youth, adulthood) — creation, destruction, giving and taking. The flesh (the fruit) and the colour red are symbols of life and sacrifice. Youth is a period of expending — some build, others destroy. “Time to throw stones and gather stones” — there is a balance in this. We all make sacrifices and give everything at this point in our lives. More or less.

The Evening (age, completion) — contemplation, silence. A meditative part. Scarcity of dinner does not mean scarcity of life, or poverty. The table is set for one person. We come alone to the end of our lives, and yet we merge face to face with the divine in this world. It is a time of transition where all matter fades and loses all meaning. I believe our spirit reaches its peak here and we either accept or reject this transition completely. The set of elements depicted is simple: the fish is the symbol of Christ, the potato (the second bread) — the body losing the spirit (steam), the black tea — the drink of the gods and sages, not for simple thirst quenching, but for contemplation. The position of the hands in the triptych refers to Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper”, in which the master emphasized the hands. Here they recede into the background and invite the viewer into this or that phase of life — past or future.”

Katerina Belkina was born in Samara in the southeast of European Russia : her mother was also a visual artist. Belkina attended the school for Photography of Michael Musorin in Samara and she’s exhibited her work in Moscow and Paris. In 2007 Katerina Belkina was nominated for the prestigious Kandinsky Prize (comparable to the British Turner Prize) in Moscow, and she has also been awarded the Hasselblad Masters Prize. She lives and works in Werder (Havel) near Berlin.

More of her work can be enjoyed here and here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Dimitri Tsykalov | MEAT | 2007 – 2008

July 28, 2023Dimitri Tsykalov | MEAT | 2007 – 2008

It’s not a new idea that firearms make acts of violence ‘too easy’, almost ‘antiseptic’, as they minimize the necessary physical contact intrinsic to other acts of brutality. This is an idea that’s been raised about technology since we began using it to kill each other.

(At the risk of seeming flippant, I must also inject a quote that came to mind when I first encountered images of Tsykalov’s MEAT : Invariably, the first question asked about a new technology is, “Can this make killing less of a hassle?” The second being, “Can I have sex with it?”…)

The implicit ‘removal’ or ‘remoteness’ (I’m reminded of the ski pole scene from Timothy Findley’s The Wars, for example, where the firearm and act of murder almost seem separate from the character himself) makes it almost a ‘trivial’ or ‘throwaway’ action to fire a gun.

Dimitri Tsykalov’s MEAT works offer a counter to that, in a grotesque manner that is excessive : I’ve debated writing about Tsykalov’s ‘armaments’ for a while, unsure if they’re too flippant, or too horrifying, or a combination of both that is as unpalatable as gripping cold flesh while your hands are stained and overrun with effluvia…

These works don’t pretend to an aesthetic distance (like in Serrano’s work, or some other artists I’ve talked about here who – like myself, when I worked with fat, bone and meat for over two decades – are interested in creating inappropriately beautiful artwork) : I feel that Tsykalov takes pleasure in our revulsion and wants to evoke it from us, and considering what he’s ‘butchering’ the meat, flesh and bone into, this is not inappropriate. There’s a swagger here, a bravado that intends to make us ill. Meat and guns are, after all, metaphors for penises or toxic masculinity, and Tsykalov alludes to that (even with the titles that reference specific guns).

Tsykalov, in creating work that intersects with brutality and our capacity for it, as a species, has taken an opposing artistic path to someone like Ralph Ziman with The Ghosts Project (a past Curator’s Pick you can see here).

Tsykalov’s own words : “In these pictures I recognize the murderers within me, I recognize love and death within me; in these pictures I recognize my flesh as the cannon fodder it is and will be for the rest of my life. In contrast the secondary meat in these shots – the one that rots and that kills, the animal meat that is used to create the fleshy weapons – seems unscathed, sanguine and elegiac. It is incredibly alive, it is cannon flesh and we are already mortal.”

Dimitri Tsykalov was born in Moscow (1963) where he attended Polygraphic Institute of Moscow (1982-1988). He currently lives and works in Paris.

More of his work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Saint Alexander Nevsky Monastery, Leningrad, USSR | Masha Ivashintsova |1977

July 21, 2023Saint Alexander Nevsky Monastery, Leningrad, USSR | Masha Ivashintsova | 1977

I was not born

to amuse the

Tsars.

— Alexander Pushkin

I loved without memory: is that not an epigraph to the book, which does not exist? I never had a memory for myself, but always for others.

— Masha Ivashintsova

Masha Ivashintsova has been described as a ‘Russian Vivian Maier‘ as she took so many photographs – creating a world, in a way, of her city – in her lifetime but most of them have only been shared since her death. Her eye for contemporary life under the Soviet regime – especially in St. Petersburg later Petrograd later Leningrad then again St. Petersburg (the shift in name and what that entails in the socio political sphere is a good place to stand, when considering Ivashintsova’s photographs) – was an honest and personal portrait of her life and times. One might argue that the veracity of these experiences captured with her lens were – are – so honest and powerful that we can understand why she held them to herself for so long. Her own personal history was also painful, and that was surely a factor, too.

Or, perhaps as I allude to with the quote from Pushkin, autocratic, authoritarian societies prefer facile propaganda and punish uncomfortable truths….

Ivashintsova (1942 − 2000) was a photographer based in Saint – Petersburg (then Leningrad, in the USSR) “who was heavily engaged in the Leningrad poetic and photography underground movement of the 1960−80s. Masha photographed prolifically throughout most of her life, but she hoarded her photo-films in the attic and rarely developed them. Only when her daughter Asya found some 30,000 negatives in their attic in 2017 did Masha’s works become public.”(from here)

“Struggling with life under Communism, by the mid-1980s Masha was committed to a mental hospital against her will, as a way to get her in line with the USSR’s philosophies. Working throughout her life as a theater critic, librarian, cloakroom attendant, design engineer, elevator mechanic, and security guard/riflewoman, she was a chameleon, always camouflaging her inner artist. Only through her diaries and photographs was she able to show her true self.”

A fine article – and interview – with her daughter Asya Ivashintsova-Melkumyan can be enjoyed here. A site devoted to Ivashintsova’s amazing archive can be seen here : as well, there is a social media page that shares her work at regular intervals here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

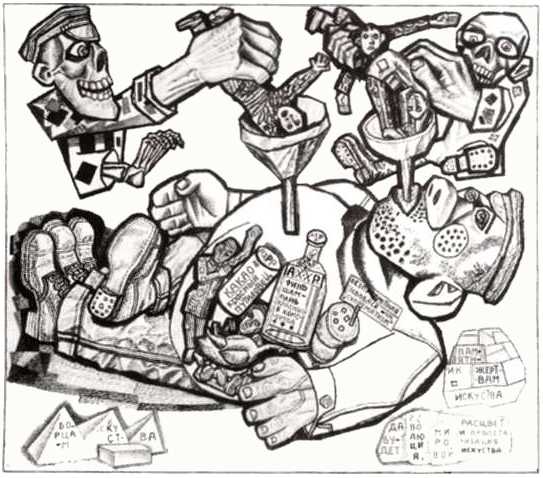

Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

October 21, 2022Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

He was walking about with a noose round his neck and didn’t know. So I told him what I’d heard about his poems.

. . . . . . . .

Yevgraf: This is a new edition of the Lara poems.

Engineer: Yes, I know. We admire your brother very much.

Yevgraf: Yes, everybody seems to.. now.

Engineer: Well, we couldn’t admire him when we weren’t allowed to read him…

Yevgraf: …No.

(both quotes from Boris Pasternak’s tale of Russia before and after the Russian Revolution Dr. Zhivago)

A defining book in my reading and understanding of art history in the 20th century is Boris Groys’ The Total Art of Stalinism: begun when the USSR was still in existence, Groys was able, with the fall of that empire, to access more information, and offer a more nuanced take upon the years post Russian Revolution, as it pertains to the arts in that rare and unique historical moment. Amusingly, I became aware of it after participating in a panel about modernism, and horrifying my fellow speakers by stating that it had failed, horribly, but that its relevance was in its ideals…

Several points stay with me, in considering Pavel Filonov’s work. One is that, in a correlation to the backward economic state of Russia making it fertile ground for a radical new approach and the subsequent revolution, the artistic milieu also suffered from this. It’s not incidental that so many significant artists – not just to Russia but to ‘western’ art history – like Malevich or the Suprematists flourished during the first heady days of the NEP. Experimentation and a sentiment that ‘anything was possible’ was pervasive and defining, with a desire to irrevocably fracture from the ‘old.’

This, of course, all ended badly, and the promised freedoms – whether artistic or personal – were soon not just reigned in, but suppressed, and a cultural exodus from the USSR to other places was predictable.

Filonov (1883 – 1941) served in WWI and would die of starvation during the siege of Leningrad, the once and present St. Petersburg, in the war that followed the ‘war to end all wars.’

The painter, art theorist and poet was an outsider, even during the pre and immediately post revolutionary days of promise: after several failures, in “1908 Filonov was admitted at last to the Academy of Arts. His works attracted the attention of both students and professors by their unusualness: they were not abstract and depicted their subject with full likeness, but were executed in garish, bright colors – reds, blues, greens and oranges. This manner did not conform to the Academy standards, and Filonov was dismissed “for influencing students with the lewdness of his work”. Filonov protested the decision of the rector Beklemishev, and was rehabilitated, but after studying for two years he left the Academy in 1910.”

He was one of many whose works were deemed degenerate, as they eschewed official socialist realist policy. He’d be lost to us, in terms of history, but for the efforts of his sister Yevdokiya Nikolayevna Glebova: “She stored the paintings in the Russian Museum’s archives and eventually donated them as a gift. Exhibitions of Filonov’s work were forbidden. In 1967, an exhibition of Filonov’s works in Novosibirsk was permitted. In 1988, his work was allowed in the Russian Museum. In 1989 and 1990, the first international exhibition of Filonov’s work was held in Paris.

During the period of half-legal status of Filonov’s works it was seemingly easy to steal them; however, there was a legend that Filonov’s ghost protected his art and anybody trying to steal his paintings or to smuggle them abroad would soon die, become paralyzed, or have a similar misfortune.”

It’s unsurprising that Filonov was deeply influence by fellow dissident Klebnikov: and his works – whether the obvious disdain present in this piece The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, or the more stark Those Who Have Nothing To Lose, or Animals, that would make a fine illustration for Orwell’s Animal Farm decades later – have an unflinching quality.

More of Filinov’s life and legacy can be learned here (and was the source cited for the biographical quotes about his life and work).

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

The Mark – Olga Volgina

August 24, 2021One of Olga Volgina’s more recent works that she’s shared on social media (as she’s a prolific artist) is a work that resonates in both an immediate and historical manner. Any (well made and meaningful) rendering of children has this power. Volgina’s children evoke a multiplicity of intersecting references: Goya’s portrait of Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga, who looks doll – like and innocent until a closer examination reveals several cats waiting to devour his pet bird, to the child’s indifference, is one. Delving even deeper into the worn faces and unflinching gaze of the children, I’m also reminded of Robertson Davies’ book World of Wonders. In response to one character relating his harsh yet essential childhood experiences, another defers that though he has experience “exploring evil” through his films, the evil of children is something that requires courage he lacks….

Volgina’s children must also bring to mind Ignorance and Want, from Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, and in that instance offer a more disturbing consideration of how a child is perhaps a larger reflection (or repository) for the world in which they live. Volgina commented that when this work – titled The Mark – was finished, “now I look at them and they look at me”, but what they see, or what they think, is opaque to us. We can guess; but the children in The Mark are silent and staring, offering no answers. Perhaps they’re indifferent to us, perhaps demanding, or perhaps simply exhausted and bruised.

Volgina lives and works in St. Petersburg, Russia. Her digital portraits, as she describes them, are both a bit unsettling and insightful. This brings to mind how sitting for some artists requires a degree of courage (never mind being nude but what of the deeper self that the artist might excavate and present for the world to see?).

See more of Olga Volgina’s work on Instagram, FB and at Etsy, where she and her twin sister, Liza Volgina, have a variety of engaging works on display. ~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

trunkdrunk

July 31, 2021Perhaps you’re familiar with the story of Pagliacci, the clown consumed by sadness he hides to make the audiences laugh. I will admit it will always be tied, for me, with Alan Moore’s Watchmen. In that graphic novel, Rorschach offers something of a lonely graveside eulogy for the character The Comedian (who ‘evolves’ from a snide position of ‘Once you realize what a joke everything is, being the Comedian is the only thing that makes sense’ to a weeping lament of “I mean, what’s so funny? What’s so goddamned funny?”). Rorshach recites a ‘joke’ about Pagliacci’s visit to a doctor, decrying his despair, only to be told by the well meaning doctor to visit the ‘famous clown’ to be cheered up. Pagliacci bursts into tears, revealing to the well meaning but unaware doctor that he is, in fact, the clown, and an empty shell who can’t even help himself…

The self described ‘comedian’ trunkdrunk occupies that same space. His Instagram page offers only that “I don’t even ask for happiness, just a little less pain.” An article on his work has the following spare and succinct comment: “trunkdrunk takes photos in Russia’s saddest places. As this was not sad enough, he takes pictures in full head overhead elephant mask. Images are captured in different places of Russia; mostly in gloomy and depressing surroundings.”

More of trunkdrunk’s images can be found on Instagram often accompanied by long swathes of text in Russian, that meld dourness, humour and memory. This image was originally posted to his IG account in October, 2016, with the following reminiscence: “Indian tea, the same – with an elephant. I remember him from my Soviet childhood. when my mother poured this Indo-Georgian mixture into a glass from a cardboard box, and then poured boiling water – the smell was stunning throughout the apartment!”

A previous Curator’s Pick of mine was a wonderful image by Alexey Titarenko: this could be said to have documented the fall of the Soviet Empire, in real time, with very real people as the unwilling players. Looking at trunkdrunk’s world, nearly forty years later, offers a new chapter to Russia history, perhaps attempting to laugh as one has no other choice, except to cry. ~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Amber Lee WIlliams – Femina Bulla Est #9

August 18, 2021The work of Amber Lee Williams, an artist from the Niagara Region of Southern Ontario, almost always concerns itself with motherhood and children, exploring the concepts of life within, the constancy of change, attachment and removal, and notions of femininity.

Femina Bulla Est (Woman is a Bubble), is a sequence of macro photographs of pink bubblegum. Amber deftly takes the binary state of man’s being, as depicted by the soap bubble in Dutch Renaissance Vanitas paintings (homo bulla est) and turns it on its ear… where man is either strong or broken, women have a strength and flexibility that allows them to persevere.

“I thought I would begin by simply blowing soap bubbles, photographing them, and seeing what happened. I asked (my daughter) if she wanted to help me blow bubbles and she thought I meant bubblegum bubbles. As soon as she mentioned the bubblegum it was a total lightbulb moment, and I have to give her credit for the idea.”

Femina Bulla Est #9 is incredibly organic, suggesting a beating heart, or the crepe-like tissue of placenta. Partially inflated, one gathers that there is life within, flush with blood and good health. One could also perceive the darker top section as a scab, protecting the soft tissue below as it heals from a trauma.

“The original bubble in Vanitas paintings suddenly pops and life ends, but in my version the bubble inflates and deflates again and again. The bubble is both fragile and resilient. Beyond the more obvious, and my personal connections to motherhood (carrying a child within my body, that body stretching…), I also think of the inflated and deflated, not just as physical states but also states of mind and related to mental health.”

You can seem more of Amber’s work at https://amberleeart.com, and on Instagram @amberlee.art. ~ Mark Walton

Read More

Recent Comments