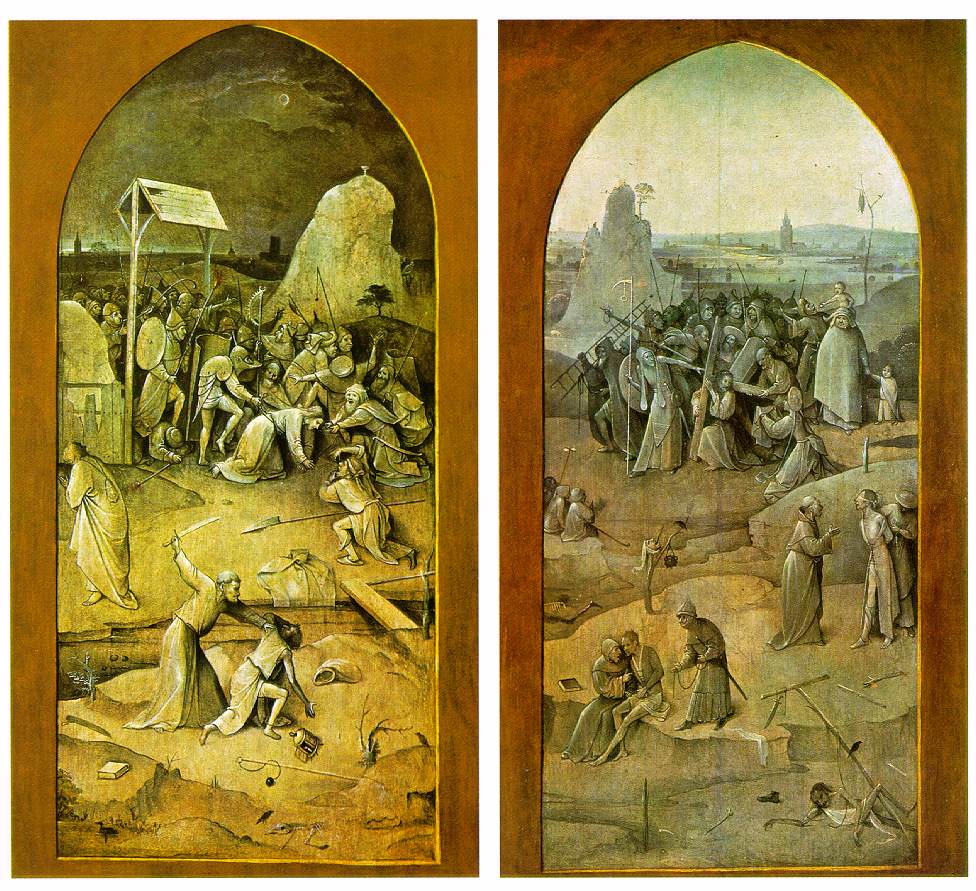

Temptation of Saint Anthony | Hieronymous Bosch

An essay by Virgil Hammock

Temptation of Saint Anthony | Hieronymus Bosch

In the summer of 2019 I was visiting my friend, Brad Walters, in Portugal: he lives part of the year there, in Caldas da Rainha which is not far from Lisbon. The rest of the year he lives in Sackville, New Brunswick, where I live as well. He also teaches at Mount Allison University where I also taught.

Recently, I convinced my good friend to visit Museu National de Art Antica to see Hieronymus Bosch’s Temptation of Saint Anthony (c1500), which is in their collection. I greatly enjoy Bosch’s work and, as with other Netherlandish artists whom I admire, I try to see in the flesh as many of their paintings as I can. Bosch is one of those artists who many people in North America admire while never seeing an actual work because there are very few (perhaps twenty-five in his own hand, while there are numerous copies and forgeries) in existence and many of the best are in Europe. Many like him for his fantastic subject matter that’s nearly unique among European artists of the 15th and 16th centuries. He was certainly popular in my crowd of San Francisco art students in the early 1960s who interpreted him in relation to the LSD drug culture of the time. We got that wrong. His work is more complex than we could understand (but then we got a lot of things wrong. Blame it on our youth).

I got it straight when I took a course in Northern Renaissance painting in graduate school at Indiana University that was heavy on iconography. There is so much more than meets the eye in many early Northern European paintings. Northern European paintings by artists like Jan van Eyck and Hugo van der Goes initially drew me in, by their sheer beauty as art objects, but at Indiana I was taught how to ‘read’ their paintings in tandem with their aesthetic values. This opened a whole new door – or perhaps I should say window – on how I understood their work.

Bosch was born c. 1453 in ‘sHertogenbosch which is now in modern day northern Holland. He died there in 1516. Both his father and grandfather were painters: this wasn’t an unusual pattern in that era as artists were craftsmen, members of guilds, and it was often a family business that spanned generations.

But let’s return to how this is the first in my forthcoming series about Looking at Pictures. There have been numerous moments, in the more than sixty years of looking at art, where I came into contact with actual artworks that have changed my life as an artist and writer. I use the word ‘actual’ because one needs to see the real thing; reproductions, especially those online, do not work and lack the vitality of the physical experience. Virtual art works are like virtual sex on the internet; interesting, but not very satisfying.

It’s often difficult to have a good look at very well known artworks because of the crowds they attract. Too many of these artworks are like the Mona Lisa (shuttered behind glass or roped off), and I’m thousands of kilometers away from my home computer office, making it harder to record or consider my response. I’m happy to say, however, that the Lisbon Bosch has none of these problems of access, as you can enjoy the work with fewer physical barriers, other than its great distance from my home across the ocean.

This triptych sits in solitary splendour, sans glass, on its own plinth in an alcove in the museum. The afternoon that we visited there was only one other person in the room (who soon left, so we could enjoy it in solitude). We could circle the open triptych, so we could view the details of the grisaille work on the front outer panels. These portray the Arrest of Christ and Christ carrying the cross. These are what viewers would have normally seen when the painting was in its original 16th century location. The painting was only opened on special occasions such as feast days and masses.

The brushwork – both on the exterior and the colourful interior panels – are a wonder to behold. It’s freely painted in an Alla Prima technique – rare for its time – which speaks to Bosch’s mastery as an artist. It’s good to remember that he was not limited to the style (as exemplified in this piece, a style he’s perhaps best known for) but also for relatively straight forward paintings like his early Crucifixion (c. 1475-80, to be found at the Musées Royal des Beaux-Art in Brussels) or his later painting (1515) titled Christ Carrying the Cross (at Musée des Beaux-Arts in Ghent). I’ve seen both of these several times, but I digress – let’s return to the front panels of the Temptation of Saint Anthony.

Much has been written about strange imagery in this and some other similar Bosch paintings. They are NOT the results of Egotism (a disease brought on by consuming rotten rye bread which results in ‘psychedelic LSD’ hallucinations also known as Saint Anthony’s Fire that was common during Bosch’s time) or psychosis. These are lucid illustrations made by a very devout Catholic artist of the pleasures and dangers of an invisible world made visible during a very dark time in European history. Heironymous Bosch was a member of the Confraternity of Notre Dame (from 1486 -1516) in ‘sHertogenbosch. He painted numerous pictures for them before he was asked to join the group, and the imagery that he painted for the group illustrated their beliefs as well as his own.

It was a time of real unrest in Europe — religious, social and economic turbulence and pestilence, as well. There was a widespread belief in Chiliasm or Millennialism that thought that world was coming to an end (the 25th of February, 1524, to be exact). We need to remember that astrology was regarded as a science, that there was fervent belief in actual demons and a certainty that Witches’s Sabbaths were also taking place. All of this can be seen in Bosch’s work.

Religious art, such as this work, illustrated for several hundred years the teachings of the church to a generally illiterate society, but often contained an iconographic code that could be read by an elite group of scholars and clerics. The stories, at times, were centred about Judgement Day and or the Second Coming when the just would be rewarded by bodily elevation to Heaven and sinners damned to Hell. This is the main purpose of The Temptations of Saint Anthony. If you fall to the temptations that were offered to St. Anthony rather than resist them as he did you surely would be doomed to the eternal suffering of Hell. The images of flying fish ridden by mermen, witches, strange animals, birds, and demons were very real to 16th century viewers of Bosch’s art – not to mention the actual temptations of the flesh via sexual inducements, and that of worldly goods.

As an atheist, I am not too bothered by Heaven and Hell, but I have always been drawn to religious art, music and the writings of many Christian philosophers (if for nothing else than their devotion that I cannot share, but can admire). I don’t want to get into an argument about the obvious shortcomings of the Christian Church which is the reason I am an atheist. I have no interest in, nor will take up the argument. What I see, and appreciate, in The Temptation of Saint Anthony by Heironymous Bosch is not unlike listening to the religious music of J.S. Bach. They both manifest a beauty that moves me to a better place than I deserve.

© Virgil Hammock, Sackville, NB Canada, 28 December 2021

Essayist

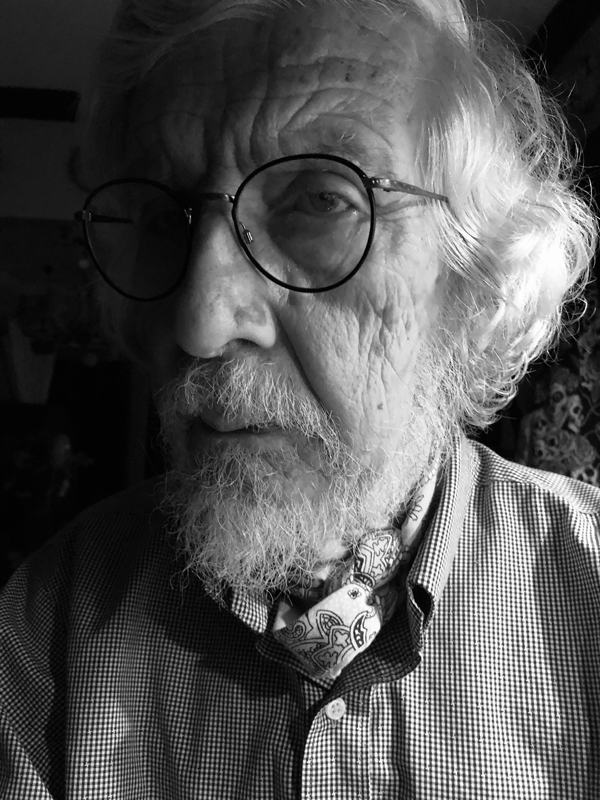

Virgil Hammock was born in Long Beach California in 1938. A Canadian citizen since 1973, He studied at the San Francisco Art Institute where a graduated with a BFA in 1965 after serving as a photographer in the US Army. He then studied at the Indiana University where he obtained a M.F.A in 1967. Appointed as instructor at the University of Alberta Department of Fine arts in 1967, he immigrated to Canada. From 1968 to 1970, he was Assistant Professor of Art, also acting as Director of University of Alberta Art Gallery and Museum. He moved to Winnipeg, where he was appointed Associate Professor of Art at the University of Manitoba from 1970−75 while being in charge also of the University Gallery 1.1.1, as Director of Exhibitions, from 1970−73. In 1975, he moved to Sackville, New Brunswick as Professor of Fine Arts and Head of the Department of Fine Arts at Mount Allison University where he taught until 2004. He also was the acting Director of the University Owens Art Gallery between 1988 and 89.The University nominated him Professor Emeritus of Fine Arts in 2005. Deeply involved in his community, Virgil has been a member of New Brunswick Arts Board, 1996−2002 and of New Brunswick Foundation for the Arts in 1999. Virgil Hammock was President of the Universities Art Association of Canada between 1973−79.

Virgil has also been also fully involved in an art criticism since 1968 when he became the art critic for the Edmonton Journal. He is the author and co author of several art books and artist monographs, including co-author 16 Quebec Painters in their Milieu 1978; Pol Mara 1990; Herman Muys en Monique Maylart 1992; Jacky DeMaeyer 1993; Edward Leibovitz 1994; vgPaul Smolder 1994; Juan Kiti 1995; Cesar Bailleux 1996; Daisy Wilford 1997; Guy Van den Bulcke 1997; Silvain 1997; Hélèn Jacubowicz 1998; Marijan Kolesar 1999; Guy Van den Bulcke: His Presence in the United States 2003. He also published numerous articles in Canadian and international journals and magazines, particularly art magazines. He was member of the editorial board of. Vie des Art (1973−80); Artfocus 1990−2011 and Artsatlantic 1999−2004. A member of AICA Canada, the Canadian Section of the International Association of Art Critics since 1973, Virgil Hammock has been a member of its board from 1975 to present and was he was twice elected its President, between 1976−80 and 1987−91. He was also Vice-President of AICA International board between 1987 and 90.

He is currently Adjunct Curator at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, New Brunswick. He curated for the gallery: Art Treasures of New Brunswick (21 Feb. to 26 May 2013), Stephen Paints a Picture (27 Feb. to 8 June 2014) and was a co-curator on Off The Grid (26 June to 14 Sept. 2014).Recent publications include The Circle Completed in Redeemed: Restoring the Lost Free Ross Mural, UNB Art Centre, University of New Brunswick (2013) and In Plain Sight, Off the Grid, Beaverbrook Art Gallery (2014). He is, since 1973, the Atlantic provinces correspondent for Vie des Arts where he publishes regularly. Published articles and commentary can be found at vigilhammock.com.

Virgil is a co-founder of the COVERT Collective.

~ Posted by Mark Walton