The Sketchbooks of Tom Forrestall

An essay by Virgil Hammock

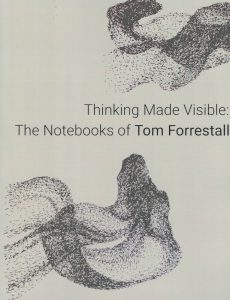

The Saint Johns Art Centre has mounted an exhibition titled The Sketchbooks of Tom Forrestall, an esteemed Maritime artist whose works have often been described as ‘East Coast Surrealism.’ Forrestall is a prolific producer of notebooks, sometimes as preliminary spaces for his paintings, but often incorporating day to day notations and commentary that – of course – also have informed his painted works. From the gallery: ‘The sketchbooks of Tom Forrestall offer an archive of unpatrolled scope documenting the artist’s creative process development and life for the last 70 years in a collection of now nearly 400 texts.’

A publication to accompany this exhibition was recently produced, with a number of arts writers contributing essays about Forrestall’s notebooks – including curated.’s Virgil Hammock. We are pleased to share his essay below.

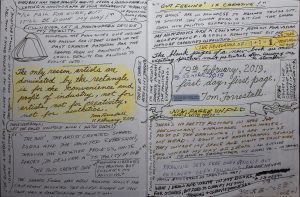

The history of artists’ notebooks goes back hundreds of years. Off the top, I can think of Leonardo da Vinci and Eugène Delacroix, but there are many others, like Edvard Munch, John Constable, and Richard Diebenkorn. I use the word notebooks rather that sketchbooks because there is an important difference. Sketchbooks are filled with drawings which often, though not always, relate to the artist’s more finished works, such as paintings or sculptures. They can be valuable to understanding an artist’s completed works. Notebooks, of the type that I am interested in, have written comments by the artist along with drawings and sketches. These notebooks are invaluable tools to understanding how an artist thinks, hence my interest in the notebooks of Canadian realist artist Tom Forrestall. I have known Tom for well over forty years and I have written many articles about his art during this time. I have mentioned his notebooks from time to time, going so far as to say they should be the subject of a book that begged to be written. This is that book.

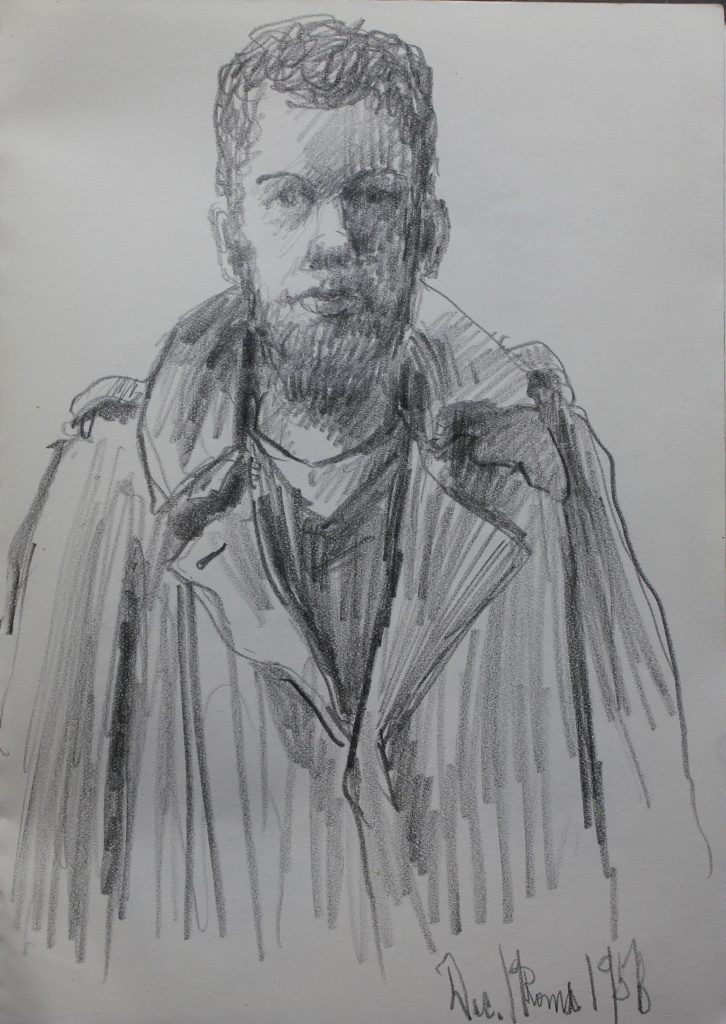

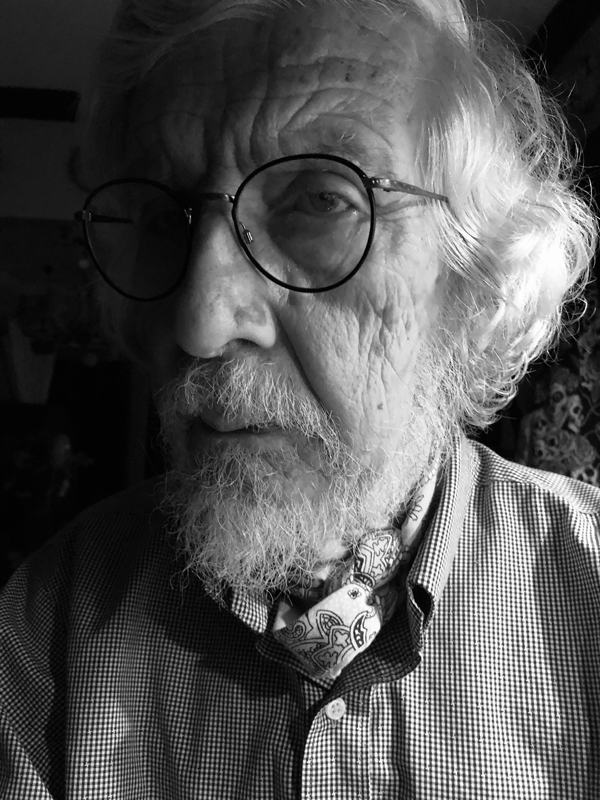

Tom, over the last sixty plus years, has filled over three hundred and eighty notebooks and will continue to fill future notebooks until death or illness stops production. They are a very complete record of an artist’s life from the mundane to profound and everything in between. Everything we do in the progress of a day is not always noteworthy, however, there are important moments that might be lost if not recorded. Artists, visual artists, think differently from non-artists; perhaps it could be better stated that they see differently. I have spent my life thinking about this difference and I am not alone. There have been countless books on the subject of visual thinking.

What is most intriguing is that in this act of seeing and creating art we use different parts of our brain from that of other kinds of thinking. Two studies that bookend my interest on this subject are Rudolf Arnheim’s Visual Thinking and Semir Zeki’s Inner Vision: An Exploration of Art and the Brain. Although thirty years separate the publication of these works the ideas remain firm that there is a science to vision and the way in which artists see. Of course, all of us with sight see. Some have 20/20 vision, others are near or far sighted, or perhaps colour blind, but what I mean is something different. It is how we process visual information within our brains that concerns me. Visual artists tend to see the world in a pictorial way. Painters, and other artists who work two-dimensional media, see the world differently than sculptors. Yes, there are artists who work in both two and three-dimensional media, but I would maintain that with few notable exceptions (such as Michelangelo) most artists have a visual basis of either two or three-dimensional vision even if they dabble in another medium than their preferred one. Picasso comes to mind: his larger sculptures seem, to my mind, paintings in three-dimensions and quite minor by comparison to his important paintings.

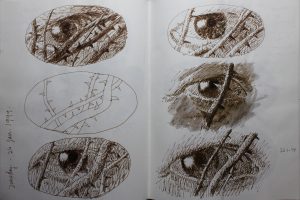

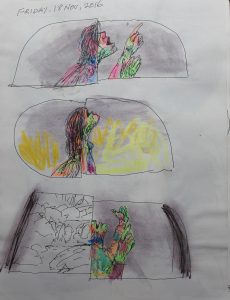

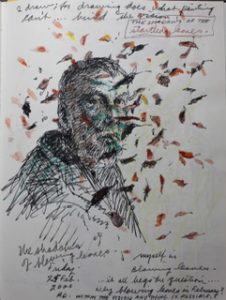

Tom’s notebooks give us a day by day, blow by blow glimpse into his thinking that spans his entire creative life. Staying at his Dartmouth, Nova Scotia home and studio, which I have done several times, I can remember going downstairs to breakfast in the kitchen to find him sitting at the table drawing and writing in a notebook. Almost all his notebooks are black bound standard size, about eight by eleven-inch, sketch books that make them handy for storage. I love that he generally only works on the right-hand page; he goes through the book, then turns it around and starts again on the right-hand page. It makes looking at the books very interesting to say the least. Even as we talked over breakfast he would often continue to draw. Sometimes I even became a subject and part of our conversation became part of his text.

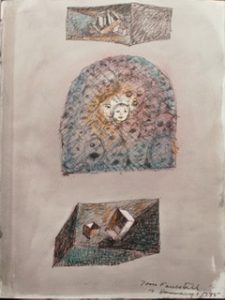

Tom looks very closely at the world he lives in. Nothing is too small. He can find a world in a teaspoon sitting on his breakfast table. Like most realist artists whom I like, he works mainly from observation and not photographs. Something that might start as a drawing from an observation in a notebook might lead to a watercolour and then to a painting. He does, however, always feel free to change things to lead to what he believes is a better finished product. Not everything in the notebooks is realistic. There is a fantasy side to some of his drawings where he creates a world that would do Hieronymus Bosch proud. The notebooks are private and his painting public. He is the owner of these two worlds. One cannot do without the other.

Sketches, being private, can allow a degree of informality and that is a good thing. It means you can throw out ideas and then reject or refine them. Writing sometime requires several drafts. Many of my musings end up in my computer’s electronic waste can. If wrote everything by hand in notebooks before committing it to text it would provide a better record of my thoughts. Alas, my handwriting is not what it used to be and I am too lazy not to write directly to my computer. Tom has a much better record of his creative life than I do. Some of this is because he works much harder than I do, but also because he puts pen to paper every day and is not afraid to record the mundane that is so much a part of life.

Even when Tom and I would go out together to a restaurant he would always lug his notebook along. While other diners would use their cell phones cameras to record things Tom would sketch. I think his results were better and certainly more interesting. They rather reminded me of the cafe drawings by Impressionist and Post-Impressionists in Paris.

His notebooks are an important extension of his creative life and are central to his thinking. One subject that Tom and I have talked about for years is his interest in shaped paintings. He plays with these shapes in his notebook drawings. I am a sort of rectangle and square guy when it comes to the format of paintings—a traditionalist. We have argued about the subject for years and I must give Tom full credit for sticking to his guns and the results are there for all to see. The notebooks will certainly provide future art historians studying his work the foundations of his thinking on his shaped works.

While I am on the subject future study of Tom’s work, it is very important that his notebooks end up in a place where they are available for the public to see, particularly scholars, artists, and art students. They will serve no purpose locked up in a dusty archive with limited, or no, access. They are, in their own way, things of beauty. I know that his son, Will, another friend of mine, is working to make sure this national treasure finds a proper home. It is nice to have this complete record of an artist’s life that proves artists can improve with age and experience. If Tom Forrestall were Japanese, he, the person, would already be a national treasure. Did I say national treasure twice? Yes, I did.

Bibliography

Rudolf Arnheim, Visual Thinking. University California Press, 1969. Semir Zeki, Inner Vision: An Exploration of Art and the Brain. Oxford University Press, 1999.

© Virgil Hammock, Sackville NB, Canada, 2022.

Essayist

Virgil Hammock was born in Long Beach California in 1938. A Canadian citizen since 1973, He studied at the San Francisco Art Institute where a graduated with a BFA in 1965 after serving as a photographer in the US Army. He then studied at the Indiana University where he obtained a M.F.A in 1967. Appointed as instructor at the University of Alberta Department of Fine arts in 1967, he immigrated to Canada. From 1968 to 1970, he was Assistant Professor of Art, also acting as Director of University of Alberta Art Gallery and Museum. He moved to Winnipeg, where he was appointed Associate Professor of Art at the University of Manitoba from 1970−75 while being in charge also of the University Gallery 1.1.1, as Director of Exhibitions, from 1970−73. In 1975, he moved to Sackville, New Brunswick as Professor of Fine Arts and Head of the Department of Fine Arts at Mount Allison University where he taught until 2004. He also was the acting Director of the University Owens Art Gallery between 1988 and 89.The University nominated him Professor Emeritus of Fine Arts in 2005. Deeply involved in his community, Virgil has been a member of New Brunswick Arts Board, 1996−2002 and of New Brunswick Foundation for the Arts in 1999. Virgil Hammock was President of the Universities Art Association of Canada between 1973−79.

Virgil has also been also fully involved in an art criticism since 1968 when he became the art critic for the Edmonton Journal. He is the author and co author of several art books and artist monographs, including co-author 16 Quebec Painters in their Milieu 1978; Pol Mara 1990; Herman Muys en Monique Maylart 1992; Jacky DeMaeyer 1993; Edward Leibovitz 1994; vgPaul Smolder 1994; Juan Kiti 1995; Cesar Bailleux 1996; Daisy Wilford 1997; Guy Van den Bulcke 1997; Silvain 1997; Hélèn Jacubowicz 1998; Marijan Kolesar 1999; Guy Van den Bulcke: His Presence in the United States 2003. He also published numerous articles in Canadian and international journals and magazines, particularly art magazines. He was member of the editorial board of. Vie des Art (1973−80); Artfocus 1990−2011 and Artsatlantic 1999−2004. A member of AICA Canada, the Canadian Section of the International Association of Art Critics since 1973, Virgil Hammock has been a member of its board from 1975 to present and was he was twice elected its President, between 1976−80 and 1987−91. He was also Vice-President of AICA International board between 1987 and 90.

He is currently Adjunct Curator at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, New Brunswick. He curated for the gallery: Art Treasures of New Brunswick (21 Feb. to 26 May 2013), Stephen Paints a Picture (27 Feb. to 8 June 2014) and was a co-curator on Off The Grid (26 June to 14 Sept. 2014).Recent publications include The Circle Completed in Redeemed: Restoring the Lost Free Ross Mural, UNB Art Centre, University of New Brunswick (2013) and In Plain Sight, Off the Grid, Beaverbrook Art Gallery (2014). He is, since 1973, the Atlantic provinces correspondent for Vie des Arts where he publishes regularly. Published articles and commentary can be found at vigilhammock.com.

Virgil is a co-founder of the COVERT Collective.

~ Posted by Mark Walton