Why Black and White Still Matters

An essay by Virgil Hammock

It can be argued that the visual world was reduced to black and white when the photograph of a man getting a shoeshine in Paris, View of the Boulevard du Temple, was taken by Louis Daguerre in 1838. It is likely the first street photograph that included people. Daguerreotypes changed the way we see the world. This is not an essay exploring the history of photography, but a reflection on the nature of reality. Portraits were painted but limited to those who could afford them before photography became commonplace in the second half of the 19th century. Knowledge of what places actually looked like was equally limited. This new reality was in black and white. While the statement about being as clear as black and white is about newsprint, black print on white paper in newspapers meant something was obviously true. The same thing can be said about peoples’ trust in photography, and in the beginning it was exclusively in black and white. Of course, newspapers can be blatantly false and photographs doctored, but most people trusted photographs to be true images of reality and certainly trusted them more than they trusted newspapers.

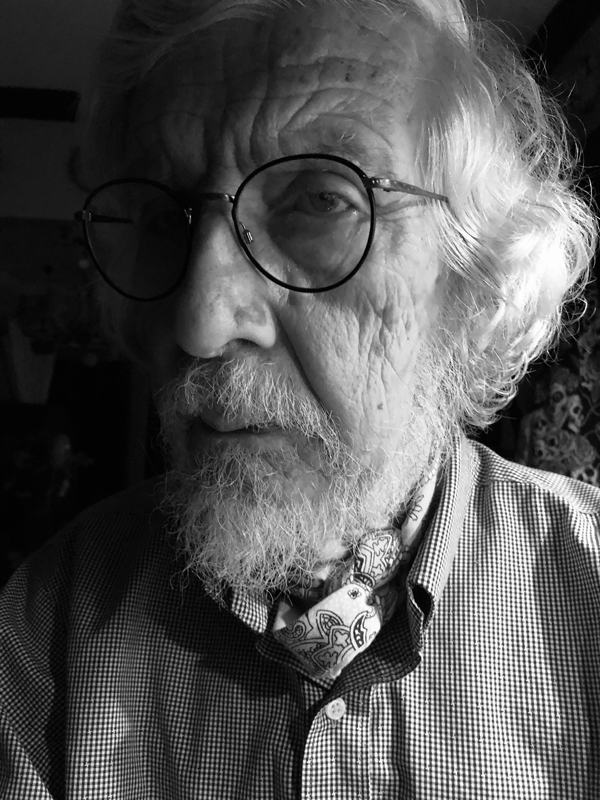

Perhaps it is because of my age (I am 83) that I am more attuned to black and white photography than colour. Black and white reduces the visual world to value and tone and gives us a new reality. That is what makes it so interesting.

I grew up as a black and white photographer. My first formal training, at the age of 18 in 1956, was as a combat photographer following a sixteen-week course at the U.S. Army photo school. I didn’t see combat, but they certainly taught me how to take a picture. Following my discharge, I enrolled in art school as a photography major. That was not to be as I changed my major to painting and later put most of my efforts into writing about art, but I still maintained a strong interest in photography as an art form. Now in my dotage, I am trying to take pictures again.

Looking at Ansel Adams’s book The Negative recently, I realized how complex photography could be at the time I was studying it. I learned the Zone System at The San Francisco Art Institute, and then The California School of Fine Arts (where Adams had taught) from his student, John Collier. Today all you have to do to get a pretty decent exposure is set the dial to A and push the shutter button. At one time I had three different exposure (light) meters—reflected, incident, and spot—and from my army training I could accurately eye-ball an exposure. This isn’t to say that this knowledge made me a better photographer – good photography is always about the photographer’s eye or vision.

To me, good black and white photography is straight photography, and by that I mean full frame with a good exposure; what the artist saw in their viewfinder. Perhaps a little cropping here and there, but not the wholesale manipulation one sees by artists using programs and apps. Perhaps that makes me a purist, though I am not stuck on the idea that good photography must be made by film cameras with images processed in darkrooms. Great black and white photographs can, and are, taken with digital cameras and printed on quality printers. A good example is to be found in The Ansel Adams Wilderness: Photographs by Peter Esstick published in 2014 by National Geographic. Esstick, using a digital camera, gives a new interpretation of Adams in his landscapes. The results are stunning. But many good photographs are taken today with smartphones. For example, I have a phone app, Lenka, that simulates an old Leica 35 film camera and does a pretty good job of it. Art is not about equipment. It is always about the artist.

I don’t want to seem that I am ‘stuck’ on the perfection of Ansel Adams. There is also a type of black and white photography that is personified by the work of Walker Evans, Robert Frank and others where a magic moment is captured forever by an artist’s vision. Their work sits at the pinnacle of street photography and it is hard to imagine it in anything other than black and white. They were the kind of photographer that I wanted to be but could not because I lacked their eye and their talent. Another problem I had with taking street photographs is that I never had the ability to make myself an invisible observer. Frankly it is even more difficult today to be an Evans or Frank when so many people object to having candid photographs taken of themselves as an invasion of their privacy, even as their lives are being constantly monitored by their own electronic devices.

Art is always defined by its time. It can be no other way. The Great Depression of the last century was elegantly recorded by photographers who worked for the American government funded Farm Security Administration, among them Dorothea Lange, Carl Mydans, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn and Russell Lee. Their work stands the test of time. When thinking of the Depression, one thinks of their photographs. Another fine example is the war photography of Robert Capa, who died following his passion for truth. This golden age of photojournalism, in the mid twentieth century, was nearly all recorded in black and white.

My own photography is about light, darkness and empty spaces. Sometimes it is about a place where people have been or are about to occupy. Often it is about the play of light across a floor, or reflections, or as common (but visually engaging) as the shadows across a washroom sink. I know when I see a picture that I want to take. It just jumps out at me. I normally envision the image as square or 1:1.5 format, the result of working with 2 1/4 by 2 1/4 or 35mm cameras many years ago. And I do see them in my mind, before I take the picture, in black and white. I still think of shoots in terms of twelve or thirty-six exposures. Old habits die hard.

Many of my friends tell me that the age of the standalone camera is over—dead. It is true that the production of real cameras is dropping, but the proclamation of their disappearance is premature. The same friends ask me “why black and white when you can have glorious colour with the same push of a button on your smartphone?” I don’t consider these people photographers. They are people with smartphones that happen to have cameras.

Everyone was talking about the death of painting when I started art school in 1959; and yet painting still seems to be around, and shows no sign of any demise. Today we hear many stating that Art itself is dead. There is no danger of that happening as long as we have people around with two eyes and the means to record a moment in time, whether it be cave painting, photography or some other medium we have not even yet imagined.

Meanwhile, I will continue to think in black and white.

©Virgil Hammock, Sackville, New Brunswick Canada, 4 December 2021.

Essayist

Virgil Hammock was born in Long Beach California in 1938. A Canadian citizen since 1973, He studied at the San Francisco Art Institute where a graduated with a BFA in 1965 after serving as a photographer in the US Army. He then studied at the Indiana University where he obtained a M.F.A in 1967. Appointed as instructor at the University of Alberta Department of Fine arts in 1967, he immigrated to Canada. From 1968 to 1970, he was Assistant Professor of Art, also acting as Director of University of Alberta Art Gallery and Museum. He moved to Winnipeg, where he was appointed Associate Professor of Art at the University of Manitoba from 1970−75 while being in charge also of the University Gallery 1.1.1, as Director of Exhibitions, from 1970−73. In 1975, he moved to Sackville, New Brunswick as Professor of Fine Arts and Head of the Department of Fine Arts at Mount Allison University where he taught until 2004. He also was the acting Director of the University Owens Art Gallery between 1988 and 89.The University nominated him Professor Emeritus of Fine Arts in 2005. Deeply involved in his community, Virgil has been a member of New Brunswick Arts Board, 1996−2002 and of New Brunswick Foundation for the Arts in 1999. Virgil Hammock was President of the Universities Art Association of Canada between 1973−79.

Virgil has also been also fully involved in an art criticism since 1968 when he became the art critic for the Edmonton Journal. He is the author and co author of several art books and artist monographs, including co-author 16 Quebec Painters in their Milieu 1978; Pol Mara 1990; Herman Muys en Monique Maylart 1992; Jacky DeMaeyer 1993; Edward Leibovitz 1994; vgPaul Smolder 1994; Juan Kiti 1995; Cesar Bailleux 1996; Daisy Wilford 1997; Guy Van den Bulcke 1997; Silvain 1997; Hélèn Jacubowicz 1998; Marijan Kolesar 1999; Guy Van den Bulcke: His Presence in the United States 2003. He also published numerous articles in Canadian and international journals and magazines, particularly art magazines. He was member of the editorial board of. Vie des Art (1973−80); Artfocus 1990−2011 and Artsatlantic 1999−2004. A member of AICA Canada, the Canadian Section of the International Association of Art Critics since 1973, Virgil Hammock has been a member of its board from 1975 to present and was he was twice elected its President, between 1976−80 and 1987−91. He was also Vice-President of AICA International board between 1987 and 90.

He is currently Adjunct Curator at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, New Brunswick. He curated for the gallery: Art Treasures of New Brunswick (21 Feb. to 26 May 2013), Stephen Paints a Picture (27 Feb. to 8 June 2014) and was a co-curator on Off The Grid (26 June to 14 Sept. 2014).Recent publications include The Circle Completed in Redeemed: Restoring the Lost Free Ross Mural, UNB Art Centre, University of New Brunswick (2013) and In Plain Sight, Off the Grid, Beaverbrook Art Gallery (2014). He is, since 1973, the Atlantic provinces correspondent for Vie des Arts where he publishes regularly. Published articles and commentary can be found at vigilhammock.com.

Virgil is a co-founder of the COVERT Collective.

~ Posted by Mark Walton