In: alternative process photography

Clarence John Laughlin | Southern Gothic

March 12, 2024Clarence John Laughlin (1905 – 1985) | Southern Gothic

Laughlin was a New Orleans photographer : he’s best known for his black and white, sometimes uncanny and disquieting images of the Southern United States. Considering the ethereal and dream like quality of many of his scenes, he’s sometimes spoken of as the father of American Surrealism. In considering his photographs, the ‘original’ definition of Surrealism from André Breton was to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality.” Less pretentiously (Frida Kahlo did refer to Breton as being among the ‘art bitches’ of Paris, whom she disdained, ahem), in the work of Laughlin, one can see that he was attempting to both re interpret and define his own memories and experiences of a site, while also employing the place and people within it, that is rife with contested narratives.

I tried to create a mythology from our contemporary world. This mythology — instead of having gods and goddesses — has the personifications of our fears and frustrations, our desires and dilemmas.

(Clarence John Laughlin)

For those unfamiliar : ‘Southern Gothic is an artistic subgenre…heavily influenced by Gothic elements and the American South. Common themes of Southern Gothic include storytelling of deeply flawed, disturbing, or eccentric characters who may be involved in hoodoo [or the large sphere of the occult], decayed or derelict settings, grotesque situations, and other sinister events relating to or stemming from poverty, alienation, crime, or violence.’ (from here)

As darkness set in, the mist drifted off the deep acreage of sugarcane that flattened back to the surrounding slough and mire. Blooming loblolly bushes, palmettos, and thick fields sprouting a type of flower he’d never seen before filled the evening air with an assertive but sweet fragrance.

The Nail family lived in an antediluvian mansion that had been built long before the separation of states. He saw where it had been rebuilt after Civil War strife and he could feel the dense and bloody history in the depths of the house. He glanced up at a row of large windows on the second floor and saw six lovely pale women staring down at him.

————————

A tremendously wide stairway opened to a landing where colonnades rose on either side abutting the ceiling. He could see the six sisters huddled together at the banister curving down from the second floor, all of them watching him, their hair sprawled over the railing. He waved, but only one of them responded, lifting her hand and daintily flexing her fingers.

(Tom Piccirilli, Emerald Hell)

The book I quote above takes place primarily in Louisiana – where the artist who’s the focus of this essay was born, and a place, whether in terms of New Orleans (his birthplace) or the greater Southern Reach (a term I borrow from another author), that defined his aesthetic. In that book, there are many dark characters that are pervasive within Southern Gothic horror that’s a wide genre, one which I’ve been quite interested in of late. The aforementioned Nail family’s daughters suffer under a ‘curse’ where they cannot speak, and seem to move about the massive manse like apparitions, veiled and almost insubstantial, like a breeze accentuated by their long dresses and hair (like so many lamenting female ghosts of the South, and elsewhere).

Another player in Emerald Hell is known only as ‘the walking darkness’ or ‘Brother Jester’ : a former evangelical preacher who, after surviving an attempt made on his life, wanders the highways and byways of the state, leaving human wreckage in his wake. A later day incarnation of Robert Mitchum’s ‘man of god’ in the film Night of the Hunter (1955), perhaps. I am also reminded of some of the desolate – but drenched in histories and stories, almost like a stain on the ground – landscapes from the first season of True Detective, which is another iteration of the essence of the Southern Gothic.

One could imagine Laughlin’s images as characters and tableaux for such a chronicle. In this sense, Laughlin is a storyteller, an historian, just like Michael Lesy, who took us on a Wisconsin Death Trip…

Ghosts exist for a purpose. Unfinished business, delayed revenge, or to carry a message. Sometimes the dead can go to a lot of trouble to bring a desperate warning of some terrible thing that’s coming.

Whatever the reason, don’t blame the messenger for the message.

(Simon R. Green, Voices from Beyond)

I attempt, through much of my work, to animate all things—even so-called ‘inanimate’ objects–with the spirit of man….the creative photographer sets free the human contents of objects; and imparts humanity to the inhuman world around him.

(Clarence John Laughlin)

Born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, Laughlin had a difficult childhood, and this – in tandem with his ‘southern heritage’ and literary interests – are touchstones for his work. The family moved to New Orleans in 1910 after further economic hardship, with his father working in a factory in the city. A quiet, introverted child, Laughlin had a close relationship with his father whose encouragement – especially in terms of Laughlin’s interest in literature – was important to his development as an artist. His father’s death in 1918 affected him greatly : the dark, funerary, epitaphic nature of much of his work, perhaps, echoes this loss.

Laughlin never completed high school, but was a “highly literate man. His large vocabulary and love of language are evident in the elaborate captions he later wrote to accompany his photographs.

Laughlin discovered photography when he was 25 and taught himself how to use a simple 2½ by 2¼ view camera. He began working as a freelance architectural photographer and was subsequently employed by agencies as varied as Vogue Magazine and the US government. Disliking the constraints of government work, Laughlin eventually left Vogue after a conflict with then-editor Edward Steichen. Thereafter, he worked almost exclusively on personal projects utilizing a wide range of photographic styles and techniques, from simple geometric abstractions of architectural features to elaborately staged allegories utilizing models, costumes, and props.” (from here)

From the High Museum of Art in Georgia (the accompanying text for a retrospective of Laughlin’s work) : “Known primarily for his atmospheric depictions of decaying antebellum architecture that proliferated his hometown of New Orleans, Laughlin approached photography with a romantic, experimental eye that diverged heavily from his peers who championed realism and social documentary.”

More about his work and life can be enjoyed here and here : and perhaps, while perusing these images, consider listening to another Southerner – Johnny Cash – and his song The Wanderer, that also offers (ironically, considering the title) a place to stand, intertwined with histories both personal and more public, when considering the photographs of Clarence John Laughlin.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Gerald Slota | Home Sweet Home | 2010

October 30, 2023Gerald Slota | Home Sweet Home | 2010

(in collaboration with Neil LaBute)

Welcome to the midnight America, the one that exists parallel to the “real” world. It’s a dark country, one where men with hooks haunt Lover’s Lane and scarecrows walk on moonlit nights. It’s the place where people go when they slip into the cracks between light and darkness, a world of routewitches and oracles, demons and ambulomancers.

The rules are different here, and everyone’s playing for keeps. Be careful. Be cautious. And listen to the urban legends, because they may be the only things that can save you from the man who waits at the crossroads, hunting souls to keep himself alive.

Welcome to the ghostside.

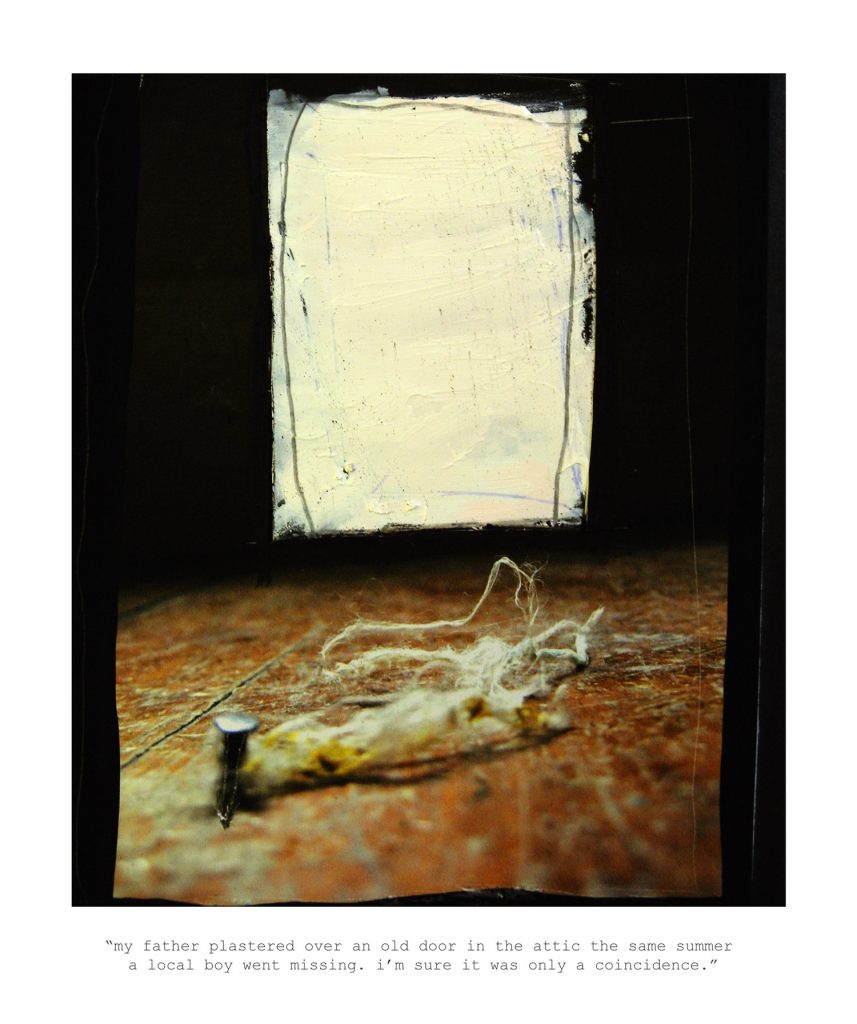

Home Sweet Home is a collaboration between Gerald Slota and playwright Neil Labute. Introduced to each other in 2008, they began corresponding and working together (via email, for the most part, as they did not actually meet in person until – fittingly – an exhibition of this work in New York City in October 2010.) From the statement about Home Sweet Home : “For the first time Slota’s visual narratives are aligned alongside written narratives. The series title serves as an ironic reference to much of the early material’s dark focus on themes of home and family.”

The world that Slota and LaBute present us with is the descendant – a successor, in some ways – of the sites and landmarks from Michael Lesy’ The Wisconsin Death Trip. Denizens of a desperate world, sometimes leading lives of ‘quiet desperation’ (but not always, as secrets fester and explode, unable to be contained forever, just as some of the ‘narrators’ of these images must share what they have held inside….)

I also interpret these as postcards from the characters in Harmony Korine’s infamous film Gummo (1997) : a ‘loose narrative follows several main characters who find odd and destructive ways to pass time, interrupted by vignettes depicting other inhabitants of the town.’ That descriptor could apply to Home Sweet Home as well as Korine’s experimental film….

LaBute – whose words offer an unsettling nuance and depth to Slota’s images here – has also observed that “we humans are a fairly barbarous bunch”…..

This isn’t a new concept—the idea that stories change things, rewrite the past and rewrite reality at the same time…

The true secret of the palimpsest skin of America is that every place is different, and every place is the same. That’s the true secret of the entire world, I’d guess, but I don’t have access to the world. All I have is North America, where the coyotes sing the moon down every night, and the rattlesnakes whisper warnings through the canyons.

The true secret of the skin of America is that it’s barely covered by the legends and lies that it clothes itself in, sitting otherwise naked and exposed.

More of Gerald Slota’s work can be enjoyed here. Slota was also a recently featured Artist You Need To Know from AIH Studios’ continuing series : that can be enjoyed here.

All italicized quotes are from Seanan McGuire‘s books Sparrow Hill Road (2014) and Girl in the Green Silk Gown (2018) from her Ghost Road series. In these stories the urban legend of ‘Resurrection Mary‘ is told from the point of view of the dead girl Rose Marshall who’s been wandering the highways and back roads of a ‘secret’ United States of America since her death in 1952….

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Alina Chirila – Femme Folks Fest 2022 Repost

March 13, 2022Alina Chirila is an experimenter. Never one to follow a rule book, she will learn the fundamentals of a process and then play with ingredients, timings and formulas until she gets exactly what she wants.

Read More

Homage II

April 20, 2021Angela Reilly’s Homage II was one of those magical experiences where art can just overwhelm you. Sitting in a pub in Glasgow on my first night ever in the UK, a series of 5 portraits hung around the room had my full attention. From a distance I thought I was looking at photographs, but close up, it was so much more. You can practically see the blood coursing through the swimmer’s veins trying to warm her up. Angela won the National Portrait Gallery’s Portrait Award in 2006 and shows regularly in the UK.

You can find Angela on Facebook, and on Instagram.

~ Mark Walton

Read More

Prairie Gothic

April 20, 2021George Webber

Rocky Mountain Books, 2013

$50.00 CND

If I was asked to pick 1 book of Canadian photography to be on a desert island with, it would be George Webber’s Prairie Gothic. I was lucky enough to be in Calgary when George had an exhibition at the small Art Gallery space downtown in 2008. The work, much of it from this book, changed me. Much like Walker Evan’s photographs in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and the American south of the depression era, Prairie Gothic is a momentous testament to the landscape and people of the Canadian West.

~ Mark Walton

Read More

IOWA

April 20, 2021Nancy Rexroth

University of Texas Press, 2017

$55.95 CND

This reprint of Nancy Rexroth’s seminal survey of images, taken with a toy Diana camera in the 1970’s, influenced a wide array of photographers, including Sally Mann, who referenced it as an inspiration in her book Sally Mann: A Thousand Crossings. Anyone who adheres to the principal of “less is more” needs to buy this.

~ Mark Walton

Read More

Fractured Flag

April 20, 2021Amy Weil’s Fractured Flag is an encaustic piece steeped in the tradition of Jasper Johns and the protest movement of the 1960’s. It caught my eye immediately as a testament to the events (and those leading up to them) of January 6th. Weil acknowledges “Whenever I put these colors together, it feels political. I don’t often pair them for that reason.”

You can find Amy on Facebook, on Instagram and at amyweilpaintings.com

~ Mark Walton

Read More

Click! The Photography of Stanley Rosenthall

April 12, 2021“Photography to me is like a kid playing in a sandbox…”

Read More

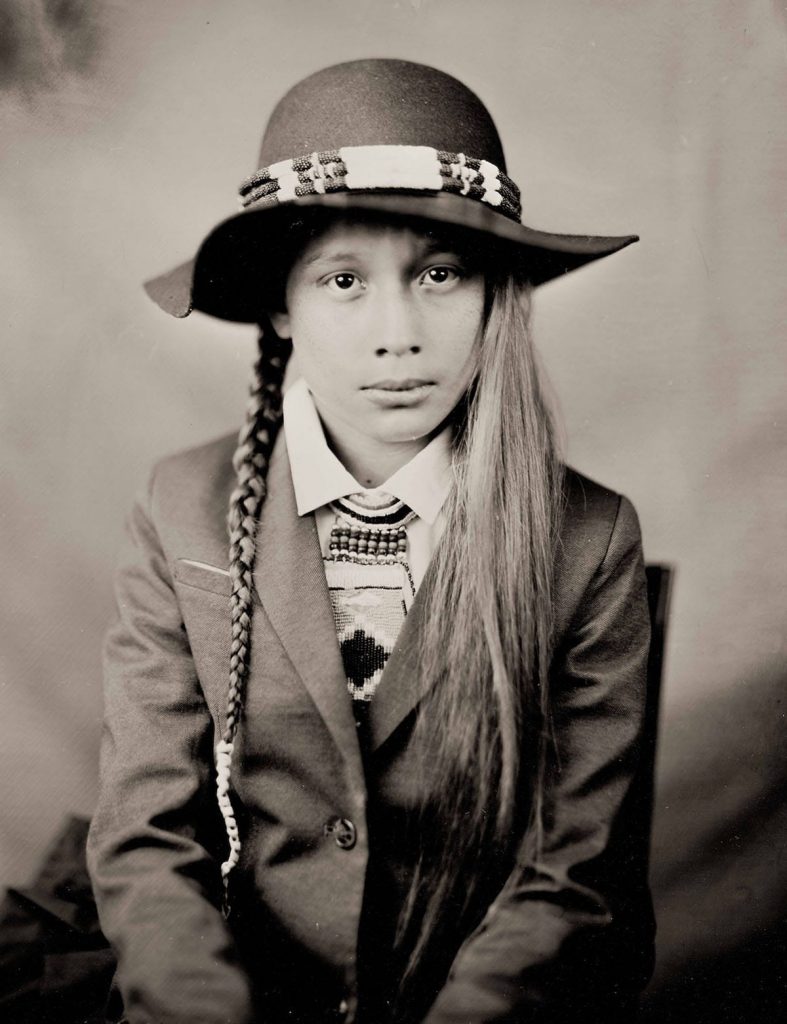

Shane Balkowitsch | Wet Plate Collodionist

January 26, 2021“Art can be a weapon for change and we artists have the ability to wield it at will”

Read More

Recent Comments