In: American Artists

Jeff Brouws | Night Window, Los Angeles, California, 2000

December 29, 2023Jeff Brouws | Night Window, Los Angeles, California, 2000

In the Far West, where Brigham Young ended up and I started from, they tell stories about hoop snakes.

When a hoop snake wants to get somewhere—whether because the hoop snake is after something, or because something is after the hoop snake—it takes its tail (which may or may not have rattles on it) into its mouth, thus forming itself into a hoop, and rolls.

Jehovah enjoined snakes to crawl on their belly in the dust, but Jehovah was an Easterner. Rolling along, bowling along, is a lot quicker and more satisfying than crawling. But, for the hoop snakes with rattles, there is a drawback. They are venomous snakes, and when they bite their own tail they die, in awful agony, of snakebite. All progress has these hitches. I don’t know what the moral is. It may be in the end safest to lie perfectly still without even crawling. Indeed it’s certain that we shall all do so in the end, which has nothing else after it. But then no tracks are left in the dust, no lines drawn; the dark and stormy nights are all one with the sweet bright days, this moment of June—and you might as well never have lived at all.

(Ursula K. Le Guin, from her essay It was a dark and stormy nigh ; or, why are we huddling about the campfire?, 1979)

A number of the images that I share in the main page for this post are also from Brouws’ American West series (1990 – 1993) and the Highway | Approaching Nowhere series. Many of Brouws’ series seem to bleed into each other, or one body of work grows into the next in a manner that does not so much interrupt his ideas as expand them.

I have a certain affinity for abandoned and derelict spaces. I do live in the rust belt wonderland of Niagara, and before that a similar zone in Windsor and Detroit (hence my appreciation of Dave Jordano‘s fine photographs), and my time on the Canadian prairies (with ghost towns in ‘next year’s country’, as captured eerily and evocatively by Danny Singer, for example) fed that interest in an overlapping manner. Brouws’ aesthetic is akin to some past Curator’s Picks I’ve featured : The Great Texas Road Story perhaps being the most immediately similar. But Brouws’ works are less despairing, with the frequency of the neon inviting glow amidst the wastelands, but like many other artists whose work I’ve featured, historical and social themes and concerns are informed by, and informing, his scenes.

“Feelings of isolation colour my photographs – that’s what you’re sensing. It’s fascinating: what’s in your mind, heart and soul gets telegraphed onto the film plane and embedded in the photograph. It can’t be avoided.”

From the Robert Koch Gallery :

“Jeff Brouws photographically explores the American cultural landscape in its myriad of facets. A self-described “visual anthropologist” with a camera, Jeff Brouws utilizes a constructed narrative and typological approach in the making of his work. Over a span of thirty plus years, Brouws has employed a diversity of themes in his work: the American highway, the franchised landscape, deindustrialized inner city zones, as well as riffing on and re-examining bodies of work by luminary artists such as Ed Ruscha, and Bernd and Hilla Becher. Brouws captures the unique cultural experience of Americana and its iconography, visually documenting a vibrant travelogue through the half-experienced, half-remembered landscape of America’s fading culture. Directing his lens toward these temporary obsolete and abandoned sites of American consciousness, he powerfully transforms images of history and dereliction into contemplative and at times humorous commentary on the collective and expressive experience of the American landscape.”

An insightful conversation with the artist can be enjoyed here. When I first encountered Brouws’ work – the primary image in this essay Night Window, Los Angeles, California, 2000 – the quote from Le Guin that opens this meditation on his work came immediately to mind. It’s all about telling stories, some of which are quieter than others, some of which are on the verge of being forgotten and some that we may never have considered. The term ‘into the west’ has connotations both positive and negative, but that is just life, and history, and Brouws’ images encapsulate all these contradictions with an eye for beauty in what might be banal, but definitely resonates with the viewer on multiple levels.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Adrianna Ault & Raymond Meeks | Ohio Farm Auction

December 11, 2023Adrianna Ault & Raymond Meeks | Ohio Farm Auction

The crops we grew last summer weren’t enough to pay the loans

Couldn’t buy the seed to plant this spring and the Farmers’ Bank foreclosed

Called my old friend Schepman up, to auction off the land

He said, “John it’s just my job and I hope you understand”

Hey, calling it your job ol’ hoss, sure don’t make it right

But if you want me to I’ll say a prayer for your soul tonight

(John Mellencamp, Rain on the Scarecrow)

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever. (Ecclesiastes 1:4, KJV)

There’s a memento mori quality to the scenes from the Ohio Farm Auction series. This may be an interpretation informed by several of the other bodies of work by Adrianna Ault (such as her series Levee which led me to the collaborative Ohio Farm Auction series), that are permeated by a sense of mortality and remembrance, as expressed in her writings about those images.

Though these images are not completely empty of people, the more striking and – unsurprisingly – starker moments that stay with you have no figures within them, though their absence and implication is powerful. The line I quote above, in response to this work came to mind immediately upon seeing the Township photos. Mellencamp’s album was a series of laments for a way of life lost (perhaps taken away or relinquished), as the world moves on (this last being closest, I feel, to the artists’ position here, with a gentle consideration of family history and generational change. Township reads more about releasing than resistance..)

The biblical quote came to me in a more indirect manner. Having recently read George Stewart’s post apocalyptic book Earth Abides (from 1949, so it ages poorly, in many ways – or this is perhaps a corolary to the ‘change’ implicit in the story presented in Ohio Farm Auction, of a time to gather and a time to discard), the ideas, again, of what is lost and our – humanity’s – place in the larger narrative of the earth was a further consideration when I engaged with these photographs…

The words of Adrianna Ault, speaking of this collaboration with Meeks (one of a number they’ve done) :

“These photographs were taken one February day in a rural township in Ohio. My partner, Raymond Meeks, and I photographed and watched as all the possessions of my family’s farm was auctioned to the highest bidder. Photographing served as a testimony to the life and work of over one hundred years of farming in my family. This work was published as a collaboration with Tim Carpenter and Brad Zellar in the book Township published by TIS books and later nominated for the 2018 Kassel Fotobookfestival Award.”

That collection of words and photographs has been described as a “careful deliberation on transience and the ultimate meaning of a way of life in the Midwest.”

More of Ault’s work can be seen here and more of Meek’s work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Gerald Slota | Home Sweet Home | 2010

October 30, 2023Gerald Slota | Home Sweet Home | 2010

(in collaboration with Neil LaBute)

Welcome to the midnight America, the one that exists parallel to the “real” world. It’s a dark country, one where men with hooks haunt Lover’s Lane and scarecrows walk on moonlit nights. It’s the place where people go when they slip into the cracks between light and darkness, a world of routewitches and oracles, demons and ambulomancers.

The rules are different here, and everyone’s playing for keeps. Be careful. Be cautious. And listen to the urban legends, because they may be the only things that can save you from the man who waits at the crossroads, hunting souls to keep himself alive.

Welcome to the ghostside.

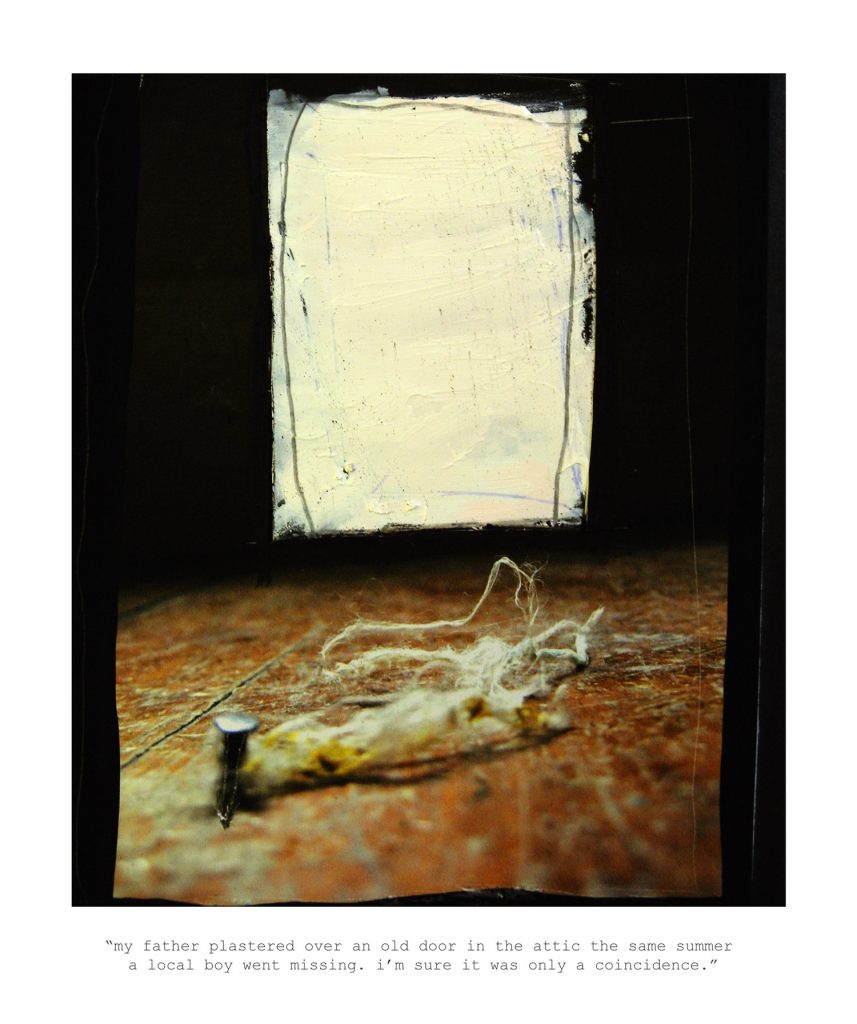

Home Sweet Home is a collaboration between Gerald Slota and playwright Neil Labute. Introduced to each other in 2008, they began corresponding and working together (via email, for the most part, as they did not actually meet in person until – fittingly – an exhibition of this work in New York City in October 2010.) From the statement about Home Sweet Home : “For the first time Slota’s visual narratives are aligned alongside written narratives. The series title serves as an ironic reference to much of the early material’s dark focus on themes of home and family.”

The world that Slota and LaBute present us with is the descendant – a successor, in some ways – of the sites and landmarks from Michael Lesy’ The Wisconsin Death Trip. Denizens of a desperate world, sometimes leading lives of ‘quiet desperation’ (but not always, as secrets fester and explode, unable to be contained forever, just as some of the ‘narrators’ of these images must share what they have held inside….)

I also interpret these as postcards from the characters in Harmony Korine’s infamous film Gummo (1997) : a ‘loose narrative follows several main characters who find odd and destructive ways to pass time, interrupted by vignettes depicting other inhabitants of the town.’ That descriptor could apply to Home Sweet Home as well as Korine’s experimental film….

LaBute – whose words offer an unsettling nuance and depth to Slota’s images here – has also observed that “we humans are a fairly barbarous bunch”…..

This isn’t a new concept—the idea that stories change things, rewrite the past and rewrite reality at the same time…

The true secret of the palimpsest skin of America is that every place is different, and every place is the same. That’s the true secret of the entire world, I’d guess, but I don’t have access to the world. All I have is North America, where the coyotes sing the moon down every night, and the rattlesnakes whisper warnings through the canyons.

The true secret of the skin of America is that it’s barely covered by the legends and lies that it clothes itself in, sitting otherwise naked and exposed.

More of Gerald Slota’s work can be enjoyed here. Slota was also a recently featured Artist You Need To Know from AIH Studios’ continuing series : that can be enjoyed here.

All italicized quotes are from Seanan McGuire‘s books Sparrow Hill Road (2014) and Girl in the Green Silk Gown (2018) from her Ghost Road series. In these stories the urban legend of ‘Resurrection Mary‘ is told from the point of view of the dead girl Rose Marshall who’s been wandering the highways and back roads of a ‘secret’ United States of America since her death in 1952….

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Scott Conary | Lamb on Paper, 2023

April 20, 2023Scott Conary | Lamb on Paper, 2023

Flesh is our indisputable commonality. Whatever our race, our religion, our politics we are faced every morning with the fact of our bodies. Their frailties, their demands, their desires. And yet the erotic appetites that spring from – and are expressed through – those bodies, are so often a source of bitter dissension and division. Acts that offer a glimpse of transcendence to one group are condemned by another. We are pressured from every side – by peers, by church, by state – to accept the consensual definition of taboo; though so often what excites our imaginations most is the violation of taboo. (Clive Barker)

Meat, weeds, eggs, bottles, and bones. What began as a way to get back to the basics of painting, without an agenda, became something else. The meat paintings are, understandably, the pieces that elicit the most questions. The first is usually, “Why meat?” The glib answer is “you can only paint so many pears.” The longer answer is that the meat is beautiful and somewhat evocative. We have a much more complicated reaction to a hunk of lamb than we do to pepper. The meat is the stuff of us. We are, after all, meat. The smell shifts while I work. The color changes. I have vivid memories of meals with family and friends built around meat. It’s beautiful, desirable, and it’s unclean. (Scott Conary)

At a very young age I encountered Alina Reyes’ novel Le Boucher [The Butcher] : consider that your only warning, before you proceed.

Let us talk about meat, about the way of all flesh, about the grotesque and evocative history of painters and photographers offering us a sense of the sensual and the shocking.

Ah, but before we get to that I must say that when I encountered Scott Conary’s work on one of my social media feeds, I was struck by it’s beauty and execution (I was unsurprised it’s painted in oils, as there’s a sensuality to that medium) and it sent me on a deeper exploration of his works.

His words also acknowledge that this choice of subject matter is neither new nor to be eschewed. Many artists have employed this trope to investigate or confront larger issues: Chaïm Soutine’s Carcass of Beef, or Rembrandt van Rijn’s Slaughtered Ox, function both as still lives – though I might use the French term of nature morte, here – but also as metaphors, whether for religion, suffering, violence or our own ongoing obsession and repulsion with our own physicality.

Conary’s renderings of meat and flesh – like many of the artists whose works I’ve shared in this post – are inappropriately beautiful.

But that beauty is tendered by how it is often metaphor, as well. One of the works I share below by Ilya Mashkov, considering the date of its execution during the Russian Civil War, is a commentary that evokes the words of his contemporary, Boris Pasternak, where his character Zhivago, speaking to the local commissar (after examining a dying man) sardonically avers that “It isn’t typhus. It’s another disease we don’t have in Moscow…starvation.” Andres Serrano‘s Cabeza de Vaca references a Spanish ‘explorer’, presented as plunder instead of plunderer, and Mark Ryden’s Meat Dress offers something for us to visually consume that explores some of the same ideas as Jana Sterbak’s Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic (which I’ve written about before) but in a more palatable form, perhaps.

Two more artists to share, that expand the conversation around Scott Conary’s meat works (I want to type that as one word – meatworks – as that seems more viscerally appropriate): Victoria Reynolds‘ art also offers “an uneasy tension between the understanding of flesh as food, and our self-identification of it; her conflation of desire, mortality, viscerality, and the survival instinct is a powerful source of aesthetic fascination.” Kanevsky, on the other hand, is primarily a figurative artist, as an American with heavy Eastern European influences. When you look at more of his work, and his preference for nudes, you may be forgiven for thinking that the work below is just painting the interior, instead of the exterior, of his ‘models’….

More of Scott Conary’s work can be seen here and his IG can be found here. His practice – and choice of subject matter – is quite varied (I was simply seduced by his meat works, if you will, but I did consider using his interpretations of eggs as a basis for a curator’s pick, as well) and worth exploring.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Martha Rosler | House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–1972

March 24, 2023Martha Rosler | House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–1972

Cotton’s generation grew up with a war in the house. For them, games of cops and robbers and cowboys and Indians no longer satisfied the senses. A boy had but to turn a control to be totally involved in the violent distension of experience that was Vietnam on television. Cotton became addicted to it. Vietnam was even a portable war.

A boy had but to move his personal set to have air strikes in the living room, search-and-destroy operations in the bedroom, naval bombardment in the bathroom—napalm before school, body bags before dinner.

(Glendon Swarthout, Bless the Beasts and the Children)

I recently read The Sacred Lies of Minnow Bly by Stephanie Oakes. The premise – of a young woman who survives a doomsday cult – sent me down a rabbit hole, if you will, of research on these cults, and since then I’ve been devouring a number of texts on the topic.

One of these – Jeffrey Melnick, Charles Manson’s Creepy Crawl: The Many Lives of America’s Most Infamous Family – offers an interesting supposition. Melnick argues that the Tate – LaBianca murders were used by many on the right – Nixon, for example – as a means by which to shutter debate about the (even then) failure of the nuclear family in the United States. This is similar to Zizek’s comment that most conversations about socialism always have a chicken little proclaiming it ‘will end in the gulag!’. Other societal issues are cast in a different light from the Manson murders, as well (for example, Melnick talks about the dismissive attitude towards runaways – especially girls – at that time, criminalizing or infantilizing them, using several of the Manson ‘family’ as examples, instead of focusing on larger issues within society).

Melnick dismisses with derision the idea that Manson ‘ended’ the supposed utopic dream of the 1960s – and for this post, a point he makes stays with me. Bluntly, that the violence of the Manson family was nary a drop in the bucket to the televised, sanctioned and officially endorsed violence of the war in Vietnam and other societal pressures. His words: “If the countercultural fabric got torn it was not because a few celebrities were killed in August of 1969. We would be better off attending to the plight of returning veterans, the not unconnected influx of harder drugs into American cities, the ongoing runaway crisis, and a major effort by the dominant culture—from the president on down—to repudiate and abandon young people and their culture.”

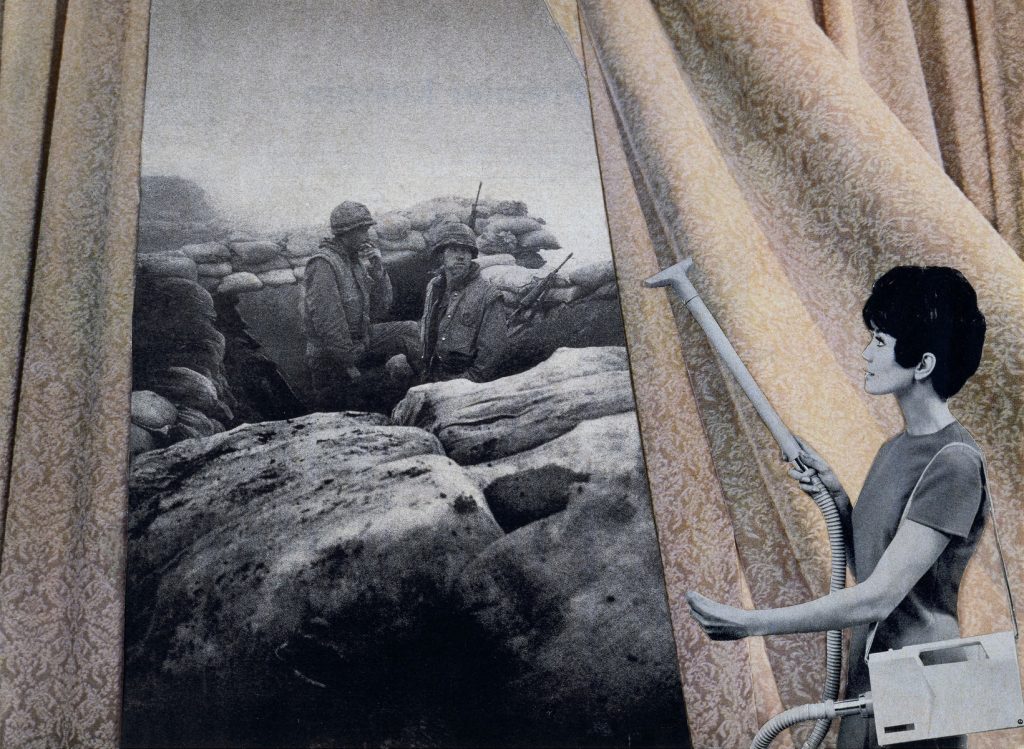

And this brings us to Martha Rosler’s series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–72.

The initial incarnation of this series was about Vietnam: in a despairing commentary about history Rosler would revisit and reinterpret it decades later, for the ‘war against terror’ in Iraq and Afghanistan…..

Rosler – in the tradition of artists like Hannah Höch – employs collage, using images that are familiar to us in tandem with others that fracture and trouble the original ‘homes’ on display. These might ‘homes’ in the literal sense, but also the ideologies and assumptions that inform those spaces, sometimes so implicitly that to highlight them engenders a denial of them, like a fish unaware of water as it’s so ubiquitous.

‘This work is one of twenty pieces from Rosler’s House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (c.1967-72) series created during, and influenced by, the Vietnam War. It was the first war in history that was literally brought into the homes of American people through the revolutionary new television set from which its horrors could be witnessed daily. It was often described as a “living room war” – a description loaded with strange poignancy as it shined a light on the eeriness of a nation living their everyday lives, ripe with consumerist concerns like keeping the stylish home drapes clean, all the while gruesome political realities took place elsewhere, becoming just another form of nightly entertainment in front of the tube.

Simultaneously, there is a feminist element to the work as it comments on the robotic mundaneness of female domestic work in the midst of global unrest. The idea of women striving to keep the house beautiful while war’s tragedies are omnipresent becomes almost comical, and presents a surreal picture about what we deem important. Recognizing the potential for manipulation in the photographic medium, Rosler once stated, “Any familiarity with photographic history shows that manipulation is integral to photography.”’ (from here)

More of Rosler’s extensive practice – and her roles as social critic and historian for more than half a century – can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments