In: Post Soviet Art

Nadav Kander | Chernobyl, Half Life, 2004

December 23, 2022Nadav Kander | Chernobyl, Half Life, 2004

I drink to our ruined house,

to the dolor of my life,

to our loneliness together;

and to you I raise my glass,

to lying lips that have betrayed us,

to dead-cold, pitiless eyes,

and to the hard realities:

that the world is brutal and coarse,

that God in fact has not saved us.

(Anna Akhmatova, I drink to our ruined house…, 1934)

I am old enough to remember when Chernobyl happened, and like many events it has become larger in the public consciousness as the years pass. In some ways, my time as a teenager had numerous events that have shaped history, as I also remember being in my high school history class and discussing the fall of the Berlin Wall, which happened a few years later.

One can’t speak of the fall of the Soviet empire without citing Chernobyl: Emmanuel LePage, in the graphic novel Springtime in Chernobyl (2012), asserts that ‘the disaster in Chernobyl is the first nail in the coffin of the Soviet Bloc.’ It is not unintentional, I think, that this metaphor is employed after an earlier passage where a widow describes the elaborate entombment of her husband’s irradiated body, like a pharaoh’s sarcophagus to hell instead of heaven…

It has become a touchstone for many artists in a variety of mediums. Some use this disaster as a means to a larger conversation. Others remind us of Stephen King’s Blind Wille reminiscing about his time in Vietnam (from Hearts in Atlantis), admitting it had much to “teach him, back in the years before it became a political joke and a crutch for hack filmwriters.”

In writing about his series Chernobyl, Half Life (2004), Nadav Kander offers the following:

“Reactor No.4 at Chernobyl’s Nuclear Power Station exploded in 1986 leaving the surrounding area uninhabitable for many hundreds of years to come. It happened to be the 20th Anniversary since the explosion when I gained access as an artist to visit Chernobyl, photographing the deserted spaces in what was once a model Soviet City.

Home to more than 40,000 people, the apartments, schools and hospitals that were hastily left following the controversial evacuation are stark reminders of past lives, leaving a disturbing sense of quiet. An uneasiness that I had never previously experienced.

There is a great beauty in a very real way to be found as the poignancy of human suffering almost hangs in the air. I found myself with a familiar feeling; best described as the feeling when walking through an overgrown cemetery on a drizzly day, but what I was looking at was far from familiar.

Having grown up with stories of relations of mine including my Father with his family that were suddenly evacuated during the second world war, I could not help but feel quite profoundly shocked as well and at the same time wonder what it must have felt like to suddenly leave your home and be transported to an unknown destination, suspecting that the near future would probably bring severe ill health due to being exposed to large doses of radiation. Little is known about the radio-active affects on the people of this city as the population were dispersed all over Russia. If there was a gathering of data by the government, it was never reported.”

I’ve selected a few of the images from this series, and most of them are focused upon spaces that would be set aside for children. Kindergarten Golden Key, Sleeping Room evokes a memory of visiting Spring Hurlbutt’s The Garden of Sleep / Le Jardin du Sommeil, which was also a contrasting beautiful space to meditate upon the death and loss of children, and both provide a focus for grief.

With work like this, there is a danger of the glorification of destruction: what one of my critical brethren has called ‘ruin porn.’ Kander, however, with his choice of sites has privileged the people – their absences are very clear, in the scenes he depicts – so that amidst all of the geo political discourse, humans and our humanity is not forgotten, willfully or otherwise….

Akhmatova’s words from half a century earlier act as a fine narration of these images: as an addendum to this pick, I’d also suggest the series Chernobyl, as it also focused upon the reality of Pripyat residents, situated within a larger historical narrative (much like Ahkamatova’s poems do).

And, with Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, some historians are reminding us of past events like the Holodomor – and in some ways, Chernobyl fits within this – where an ’empire’ exhibits cruelty and disregards humanity, whether through malevolence or ignorance, and sometimes I see Chernobyl through this lens, as well….

There is a surfeit of cultural commemoration or interpretation of this event and some is better than others. Kander’s work is quietly unsettling, even after all these decades.

More of this series can be seen here.

IG: @nadavkander

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Elena Chernyshova | Days of Night / Nights of Day, 2012-2013

December 8, 2022Elena Chernyshova | Days of Night / Nights of Day, 2012-2013

‘I was with my people then, there, where my people, unfortunately, were.’

(Anna Akhmatova, Requiem, 1935 – 1961, writing of her times in the soviet gulag)

When I lived in Saskatoon, an acquaintance who’d spent time in Eastern Europe once commented that that city in winter was like Siberia, but without the cachet of being that place (which exists as much in our imaginations as it does in reality, one might say – as a ‘great part of the imagination of the world is attached to that site’), nor with architecture that was anything but a failed brutalism (this was during a period with the ‘economic boom’ in Saskatoon where a number of heritage buildings were lost and the banal taupe of others rose like mottled angular tumours….)

Elena Chernyshova’s work is aesthetically stunning: not just for the evocative quality of the images, but also for the scenes they present to us, that seem to blend exotica and danger, a chronicle of sites that remind us of the irrelevance of humanity in the face of nature.

But her notes and comments bring the human element back, as this is not just a ‘pretty’ image, but a site of – of course – contested narratives, that looks back to the history of the USSR and some of the ideas of industrialization and ‘progress’ that have human costs.

Chernyshova’s own words are a powerful adjunct to her lens: “Days of Night / Nights of Day is about the daily life of the inhabitants of Norilsk. Norilsk is a mining city, with a population of more than 170,000. It is the northernmost city (100,000+ people) in the world. The average temperature is -10° C and reaches lows of -55° C in the winter. For two months of the year, the city is plunged into polar night when there are zero hours of sunlight.

The entire city, its mines and its metallurgical factories were constructed by prisoners of the nearby gulag, Norillag, in the 1920s and 30s. 60% of the present population is involved with the city’s industrial processes: mining, smelting, metallurgy and so on. The city sits on the world’s largest deposit of nickel-copper-palladium. Nearly half of the world’s palladium is mined in Norilsk. Accordingly, Norilsk is the 7th most polluted city in the world.

This documentary project aims to investigate human adaptation to extreme climate, environmental disaster and isolation. The living conditions of the people of Norilsk are unique, making them an incomparable subject for such a study.”

Chernyshova offers the following about the image of monumental architecture (with a blue suffusing light): The construction plan of Norilsk was established in 1940, by architects imprisoned in the nearby Gulag. The idea was to create an ideal city. The most “ancient” buildings are constructed in the Stalinist style. The next step of construction happened in the 60s, when the prevailing method in the USSR was to use pre-built panels.

Her other writings also allude to the disputed, if not adversarial, stories that meet and intersect in Days of Night / Nights of Day. The scene with the car and hazy clouds the colour of sulfur has the following notation: In the summer, there is a period when the sun doesn’t go under the horizon. This continues from the end of May till the end of July. It is accompanied by good weather and pleasant temperatures. Around 3 am, while the city sleeps, it is still illuminated by the sun. The city seems like a ghost town, emptied of its inhabitants.

One of the images I’ve included from Chernyshova’s series is unlike the others: and its difference helps to offer insight into the whole. Again, Chernyshova’s voice must be borrowed: Anna Vasilievna Bigus, 88, [who] spent ten years of her youth in the Gulag. At age 19, she was separated from her family and sent into the Arctic Circle. “The only joy we could have in Gulag was singing. We sang a lot. And this gave us the strength to survive…” Her daughter became a music teacher and her grandchildren sing in opera.

The complete series (produced with the support of The Jean-Luc Lagardère Foundation) can be seen here and a feature from LensCulture (where Chernyshova offers some words about many of the images I’ve shared here, that offer more nuance and depth to her vision) can be enjoyed here.

Elena Chernyshova’s site

@elena.chernyshova.photography

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

October 21, 2022Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

He was walking about with a noose round his neck and didn’t know. So I told him what I’d heard about his poems.

. . . . . . . .

Yevgraf: This is a new edition of the Lara poems.

Engineer: Yes, I know. We admire your brother very much.

Yevgraf: Yes, everybody seems to.. now.

Engineer: Well, we couldn’t admire him when we weren’t allowed to read him…

Yevgraf: …No.

(both quotes from Boris Pasternak’s tale of Russia before and after the Russian Revolution Dr. Zhivago)

A defining book in my reading and understanding of art history in the 20th century is Boris Groys’ The Total Art of Stalinism: begun when the USSR was still in existence, Groys was able, with the fall of that empire, to access more information, and offer a more nuanced take upon the years post Russian Revolution, as it pertains to the arts in that rare and unique historical moment. Amusingly, I became aware of it after participating in a panel about modernism, and horrifying my fellow speakers by stating that it had failed, horribly, but that its relevance was in its ideals…

Several points stay with me, in considering Pavel Filonov’s work. One is that, in a correlation to the backward economic state of Russia making it fertile ground for a radical new approach and the subsequent revolution, the artistic milieu also suffered from this. It’s not incidental that so many significant artists – not just to Russia but to ‘western’ art history – like Malevich or the Suprematists flourished during the first heady days of the NEP. Experimentation and a sentiment that ‘anything was possible’ was pervasive and defining, with a desire to irrevocably fracture from the ‘old.’

This, of course, all ended badly, and the promised freedoms – whether artistic or personal – were soon not just reigned in, but suppressed, and a cultural exodus from the USSR to other places was predictable.

Filonov (1883 – 1941) served in WWI and would die of starvation during the siege of Leningrad, the once and present St. Petersburg, in the war that followed the ‘war to end all wars.’

The painter, art theorist and poet was an outsider, even during the pre and immediately post revolutionary days of promise: after several failures, in “1908 Filonov was admitted at last to the Academy of Arts. His works attracted the attention of both students and professors by their unusualness: they were not abstract and depicted their subject with full likeness, but were executed in garish, bright colors – reds, blues, greens and oranges. This manner did not conform to the Academy standards, and Filonov was dismissed “for influencing students with the lewdness of his work”. Filonov protested the decision of the rector Beklemishev, and was rehabilitated, but after studying for two years he left the Academy in 1910.”

He was one of many whose works were deemed degenerate, as they eschewed official socialist realist policy. He’d be lost to us, in terms of history, but for the efforts of his sister Yevdokiya Nikolayevna Glebova: “She stored the paintings in the Russian Museum’s archives and eventually donated them as a gift. Exhibitions of Filonov’s work were forbidden. In 1967, an exhibition of Filonov’s works in Novosibirsk was permitted. In 1988, his work was allowed in the Russian Museum. In 1989 and 1990, the first international exhibition of Filonov’s work was held in Paris.

During the period of half-legal status of Filonov’s works it was seemingly easy to steal them; however, there was a legend that Filonov’s ghost protected his art and anybody trying to steal his paintings or to smuggle them abroad would soon die, become paralyzed, or have a similar misfortune.”

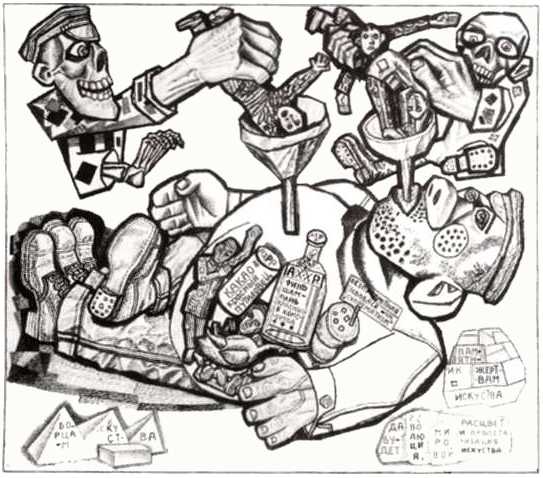

It’s unsurprising that Filonov was deeply influence by fellow dissident Klebnikov: and his works – whether the obvious disdain present in this piece The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, or the more stark Those Who Have Nothing To Lose, or Animals, that would make a fine illustration for Orwell’s Animal Farm decades later – have an unflinching quality.

More of Filinov’s life and legacy can be learned here (and was the source cited for the biographical quotes about his life and work).

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Lara Vychuzhanina | The life of Barbie and Ken in the Soviet Union

November 30, 2021Lara Vychuzhanina | The life of Barbie and Ken in the Soviet Union, 2017

First as tragedy, then as farce, we were warned a long time ago by Marx, is how history will play out. That’s a bit damning, but as we make our way further into the 21st century, it’s to be forgiven if many of us also see a more black than bleak humour in all this, a dark comedy that still makes us laugh, inappropriately.

Lara Vychuzhanina (whose Instagram name is aptly @lara_art_dolls) is a Russian photographer from Yekaterinburg – formerly known as Sverdlovsk, during the Soviet era, which I mention as it intersects with some of the ideas present in her work here, where she’s created a tableaux of Barbie and her partner Ken living in the USSR in the 1980s.

There’s always an element of nostalgia in depictions of history, allusions to a ‘simpler time’, and it’s interesting to see one about the USSR, as in the West we’re usually inundated with this false trope about the 1950s, or 1960s: Lara Vychuzhanina is too young to remember the 1980s in the former Soviet Union, but this doesn’t stop others from offering caustic and contested interpretations of those eras, either. Employing Barbie and Ken for this is a nice intersection of mythologies of East and West, capitalism and communism, plasticity and reality – and it is also, in the inherent contradictions of its assemblage, very funny.

After all, “comedy is in act superior to tragedy and humourous reasoning superior to grandiloquent reasoning” (which, fittingly, is attributed to Friedrich Engels by Karl Marx, back in 1862)…..

More images by this artist can be enjoyed at her Instagram. ~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments