In: Bart Gazzola

The Death of the Artist | William Deresiewicz, 2020

June 3, 2022The Death of the Artist: How Creators Are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech | William Deresiewicz, 2020

I cannot think of another field in which people feel guilty about being paid for their work—and even guiltier for wanting to be.

This is – bluntly – a difficult book. It was necessary for me to read it in installments, and I know that many of my friends who are artists had to do the same. Perhaps it was like a series of inoculations against a disease, spaced out to have maximum curative effect. It motivated me to revisit Robert Hughes’ essay Art and Money, from his book Nothing If Not Critical, and simultaneously I was reading Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code by Primavera De Filippi and Aaron Wright (as part of my ongoing attempt to understand the phenomenon of NFTs better). Three decades separate those two books, and they make an interesting extended bibliography to The Death of the Artist. Sometimes there’s concurrences, more often disagreement, and a feeling that more time must have passed between their publication, as the gulf is so wide that Doris Lessing’s idea that ‘nothing seems more improbable than what people believed when this belief has gone with the wind’ floated in the air, as I read.

For anyone who’s worked in culture, or has attended art school or various other educational institutions focused upon producing ‘creators’, there are numerous assertions made in William Deresiewicz’ book that will ring true, in a rueful manner that many of us may have denied (or sadly, will continue to do so, unto the pauper’s grave). Some of the stories from the artists – of various stripes – that Deresiewicz spoke with, that inform this book, will be very familiar. My own experience in public galleries or artist run centres, and attempting to negotiate being a cultural worker in other spheres, match the stories here.

This book might offend you, but it will offend you in all the correct ways, and perhaps offend all the appropriate people.

If art is work, then artists are workers. No one likes to hear this. Nonartists don’t, because it shatters their romantic ideas about the creative life. Artists don’t either, as people who have tried to organize them as workers have told me. They also buy into the myths; they also want to think they’re special. To be a worker is to be like everybody else. Yet to accept that art is work—in the specific sense that it deserves remuneration—can be a crucial act of self-empowerment, as well as self-definition.

A tangent, not unrelated, if I may, that aligns with Deresiewicz’ research: a friend is an artist, exhibiting widely, and has been teaching as a sessional for several years. She is me, twenty years ago: she has less protection, security and opportunity than I did, despite both of us doing ‘all the right things.’ We are – like many workers – in a steady decline, that seems not only unstoppable, but unrecognized. Another gem from Deresiewicz’ book: The writer and visual artist Molly Crabapple, another exemplary leftist, puts it like this in her essay “Filthy Lucre”: “Not talking about money is a tool of class war.”

Art is hard. It never just comes to you. The idea of effortless inspiration is another romantic myth. For amateurs, making art may be a form of recreation, but no one, amateur or professional, who has tried to do it with any degree of seriousness is under the illusion that it’s easy. “A writer,” said Thomas Mann, “is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.” More difficult, because there is more for you to do, more that you know how to do, and because you hold yourself to higher standards.

If I ever dared to revisit academic or educational spaces – or if I was let back in – this text would be required reading, not just for those wanting to become artists, but especially for those who would go on to be gallerists, cultural workers and even players within the political sphere, as in some ways this book is a warning. But there’s a large dollop of Cassandra in cultural spaces, especially in Canada (several years ago, I was pilloried for shaming an artist run centre for not paying emerging artists, but the abuse was worth it as they – eventually – did the right thing). Deresiewicz’ research, and the testimonials in this book, can help break that complacency….

The Death of the Artist: How Creators Are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech is not so much a warning, as a reality. It is a severe, but indispensable, book.

All quotes in italics are from Deresiewicz’ book. As usual, I suggest visiting a local bookstore (such as Someday Books) to pick up this text.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Around the Red | Viktor Balaguar

April 14, 2022Around the Red | Viktor Balaguar

Balaguer’s series Around the Red (which includes the image shared here) is perhaps my favourite of his series (a hard decision, though, as Teriberka or Street Photography for Xiaomi are enchanting, too).

Often, his images of St. Petersburg and Moscow suggest a perpetual winter in Russia, but these are less so of that style. The vibrant reds – which never seem forced and hold your eye without overly dominating the scene – run through these works, which are captured moments of places and people. The title implicates historical factors, of course, as Russia and the world are still negotiating the rise and fall of the USSR, in contemporary Russia and beyond those borders (sometimes acknowledging what happened, sometimes not, as we dance ‘around the red’). There is no point when ‘then’ stops and ‘now’ begins in sites of contested narratives (like St. Petersburg or Moscow, Eastern Europe or even in a larger world history), and Balaguer’s Around the Red sometimes hints – and sometimes hammers – at that, visually.

I should add that I began writing this post prior to the most recent acts of war by Russia, but that simply adds more weight to the geo – political insinuations of Balaguer’s scenes….perhaps, as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn warned us in his The Gulag Archipelago if you “dwell on the past…you’ll lose an eye. Forget the past and you’ll lose both eyes.” To be honest, I had mixed feelings about sharing this work, considering the current political climate, but will temper that with the recommendation of Timothy Snyder’s book Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, from 2010…..

From here : French photographer, architect and interior designer Viktor Balaguer fell in love at first sight with the ‘Venice of the North’ where he has settled with his family. “Saint Petersburg is a romantic city where you can go from a narrow street to wide avenues, where you follow the sublime and immense Neva River that is completely frozen for part of the year,” he said, calling it “A city of strong contrasts, with a succession of magical palaces and imperial facades whose entrance gates you must cross and visit the dark backyards of the Soviet era. A city deeply melancholic by nature, immersed in a relaxing rhythm of life and permanently open to contemplation.”

In selecting this image, I had a difficult time, as any of the vignettes in Around the Red by Balaguer are worthy of consideration: you can see more of them here, and many of his other fine images at both his IG: @viktor_balaguer and his site.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

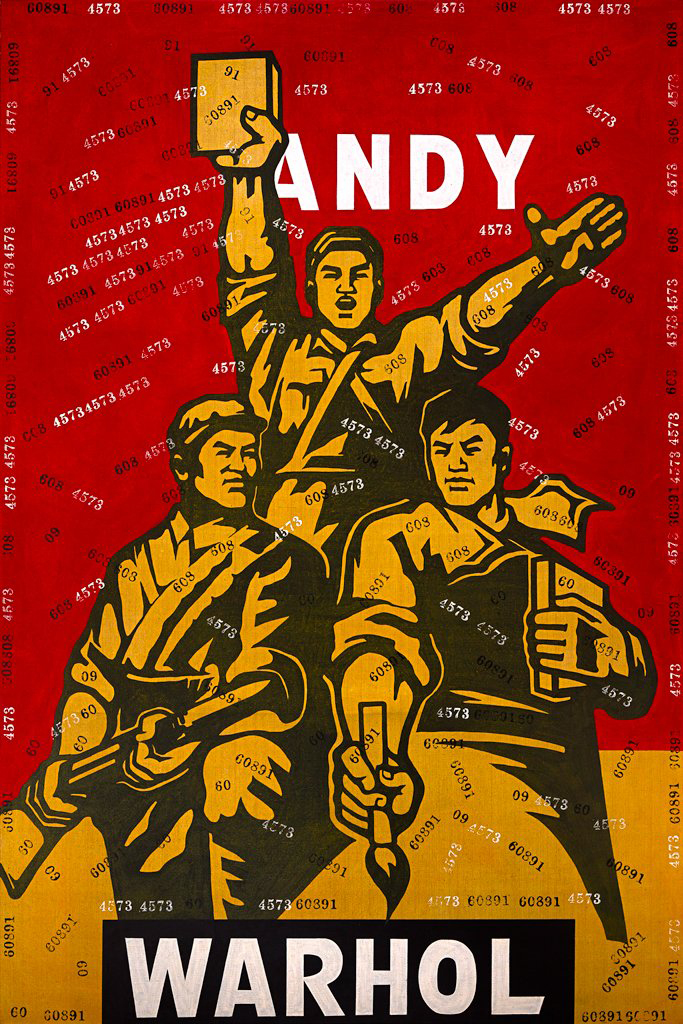

Great Criticism Series: Andy Warhol, 2001 | Wang Guangyi 王广义

April 7, 2022Great Criticism Series: Andy Warhol, 2001 | Wang Guangyi 王广义

A few years ago I re-read George Orwell’s All Art Is Propaganda. Orwell is a hot topic these days, too often cited by those who haven’t read him and barely – or refuse to actually – understand the points he was making. Here in Niagara, a mayor responded to an appropriate censure – and consequences – for his dishonesty and religious gibberish by misquoting Orwell, and his smug ignorance was more akin to what Orwell opposed, and criticized, than what the author supported.

Propaganda is perhaps most dangerous not when we can recognize it, but when it has become ubiquitous – and this is on my mind when encountering the works of Chinese artist Wang Guangyi (王广义), who (in that often sloppy way that art historians and critics try to slap a label on something, dismissing nuance and dissent) has been described as a Chinese Political Pop Artist.

There is much more at play here than that: “I came to realize that the essence of art is its ancestry, its history,” the artist has said. “When creating a work of art, one’s head is full of these historical considerations; an encounter with what has been and its entry into the process of rectification.”

“Great Criticism is Wang Guangyi’s most famous cycle of works. These works use propaganda images of the Cultural Revolution and contemporary logos from Western advertisements. Wang Guangyi began this cycle in 1990 and ended it in 2007 when he became convinced that its international success would compromise the original meaning of the works, namely that political and commercial propaganda are two forms of brainwashing.”

An interesting and subtle allusion to the vagaries of propaganda and control are in the ‘two repeating, randomly selected numbers [that] can be found stamped across the composition. During the Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976), two licenses were required for the production of any image for public consumption: one to produce the image, and another to distribute it. These numbers then reference the extreme restrictions on creative production during Wang’s formative years.” (from here)

Slavoj Žižek has asserted (or warned, edit as you will) that we can imagine the end of the world more easily than we can imagine the end of capitalism. Another intersecting trope – and why I chose this work, of his many fine pieces in this series, that lumps in the idea that is ‘Warhol’ with other capitalist monoliths like McDonalds, Disney or Pepsi – is the rise of the NFT in the larger art world, where money not only ‘creates’ taste, but invalidates any other dissenting concerns. Or, as Warhol warned us, Art is what you can get away with…just like propaganda.

Wang Guangyi (王广义)’s site is here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

The Whisper | Cecilia Paredes, 2021

March 31, 2022The Whisper | Cecilia Paredes, 2021

“I’ve got out at last,” said I, “in spite of you and Jane. And I’ve pulled off most of the paper, so you can’t put me back!”

Now why should that man have fainted? But he did, and right across my path by the wall, so that I had to creep over him every time!”

(The Yellow Wallpaper, Charlotte Perkins Gilman)

Paredes’ self portraits are unsettling: in this one, she actually makes eye contact with us, making it harder to ignore, yet easier to ‘find’ her, within the composition. Though her work is a performative metaphor for our relationship with the environment, one can’t help but also see a statement about women and the still too frequent dismissal of female artists, in her artworks. The ‘wallpaper’ of The Whisper – in conversation with a friend – brought to mind the story I cited at the beginning of this piece, which was published in 1892, and touches upon many of the themes I’ve mentioned. This story can be read here: but I offer a brief taste of its haunting narrative below.

The narrator devotes many journal entries to describing the wallpaper in the room – its “sickly” color, its “yellow” smell, its bizarre and disturbing pattern like “an interminable string of toadstools, budding and sprouting in endless convolutions,” its missing patches, and the way it leaves yellow smears on the skin and clothing of anyone who touches it. She describes how the longer one stays in the bedroom, the more the wallpaper appears to mutate, especially in the moonlight. With no stimulus other than the wallpaper, the pattern and designs become increasingly intriguing to the narrator. She soon begins to see a figure in the design. Eventually, she comes to believe that a woman is creeping on all fours behind the pattern. Believing she must free the woman in the wallpaper, she begins to strip the remaining paper off the wall.

‘Cecilia Paredes creates self-portraits that play with disguise and metamorphosis. She is known for a series in which she appears to vanish into a graphic backdrop. These “photo performances,” as the artist calls them, often involve her painting herself with bright, intricate patterns before documenting her body against a wall of the same motifs. Influenced by nature, Paredes also transforms herself into animals in realistic, glamorous studio portraits….Paying tribute to the flora and fauna of her native Peru, Paredes creates layered statements of her own identity. Her works also speak to humans’ relationship with nature and our responsibility to threatened environments.’ (from here)

More of her work can be seen at her Instagram @ceciliaparedesarte and a longer article about this series can be enjoyed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Maria Simmons – Fermentation of Ideas – Femme Folks Fest Special

March 17, 2022Maria Simmons Fermentation of Ideas The COVERT Collective is pleased to be participating in Femme Folks Fest 2022. Maria Simmons is an eclectic,... Read More

Gabrielle de Montmollin | Weird Baby World – Femme Folks Fest Repost

March 14, 2022Gabrielle de Montmollin’s installation Weird Baby World is both engaging and eerie, employing iconography that is evocative and somewhat unsettling. Bart Gazzola offers a response to this street level exhibition, on display at Niagara Artists Centre (NAC) in St. Catharines.

Read More

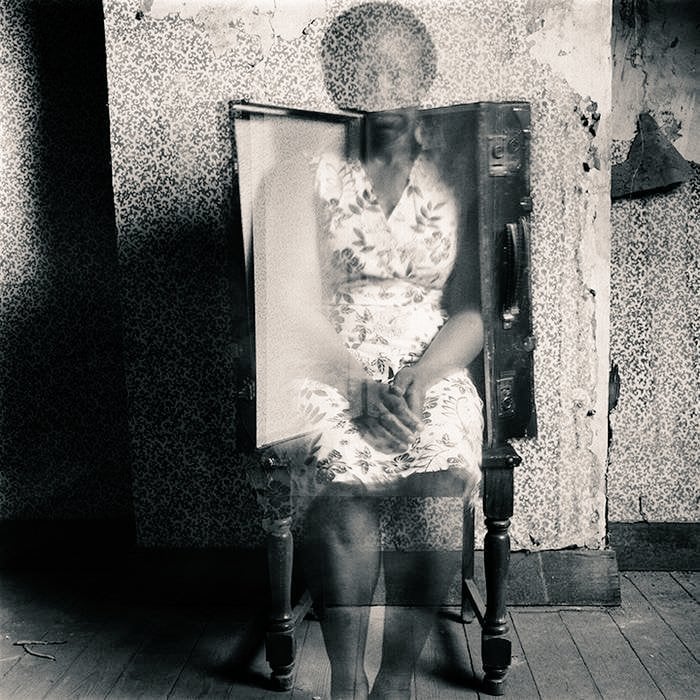

Hélène Amouzou | Between the Wallpaper and the Wall, Belgium / Togo, 2004-2011

March 24, 2022Hélène Amouzou | Between the Wallpaper and the Wall, Belgium / Togo, 2004-2011

Foreigners forget their place (having left it behind). Given time, they begin to think of themselves as our equals. It is an unavoidable hazard. (Salman Rushdie, Christopher Columbus and Queen Isabella of Spain Consummate Their Relationship, Santa Fe, January, 1492, from his book East, West)

Rushdie’s characters are dripping with entitled sarcasm, in that story I cited. They could never imagine themselves as being foreign, or displaced, or not the gatekeepers – or the owners – of a place. Hélène Amouzou’s images from her series Between the Wallpaper and the Wall, Belgium/Togo, 2004-2011 originate from the opposite side of that conversation, and the ghostly, ephemeral nature of her self portraits speaks to a doubt, a dismissal, even, that is too often the immigrant experience.

“They describe us,” the other whispered solemnly. “That’s all. They have the power of description, and we succumb to the pictures they construct.” (Rushdie, again, from the chapter Ellowen Deeowen, of The Satanic Verses, entailing the suffering of immigrants in a manner that is both a casual brutality and magical realism, where words become reality. If you’re familiar with this text, the idea that someone might fade from sight, like dissipating mist if willfully ignored, fits right in….).

Inspired by the work of Francesca Woodman, Hélène Amouzou creates her own distinctive and haunting imagery, which speaks of the contemporary issue of the displacement of people and those in exile. Born in Togo, Amouzou now lives and work in Belgium. The photographs were taken during a two year period when Amouzou was seeking asylum there and waiting for her official residency visa. She captures herself or her belongings (often her clothes) in an empty room with peeling floral wallpaper. In many of the images she includes a suitcase as a recurrent symbol of her state of flux and transit. She works with film rather than digital media, preferring the effects of chance and serendipity and she exploits the use of long exposures, playing with the photographic medium to create ephemeral and ghostly self-portraits. “Self-portraiture is a way of writing without words,” Amouzou says. “My aim is to reveal the deepest parts of myself.”

These photographs reveal a constant questioning and search for the subject’s identity. Notions of freedom and legitimacy are explored in a world of bureaucracy and inequalities. Amouzou captures feelings of exclusion and the stigmatization by the lengthy official process. Those with permanent residency rights can only imagine the insecurity and daily worry of the possibility of being sent back to an unsafe place and the photographs reveal this sense of impermanence. Her ghostly images haunt each frame and hover in the no-man’s land between absence and presence. (from Juxtapoz)

More of Hélène Amouzou’s work can be seen here. ~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Jerusalem floor, 2012 | Larissa Sansour

March 22, 2022Jerusalem floor, 2012 | Larissa Sansour

Jerusalem floor, 2012 | Larissa Sansour, C-print (23 3/5 × 47 1/5 in / 60 × 120 cm)

On the flight from London I sit opposite a rumble seat where the stewardess places herself during takeoff. The stewardess is an Asian woman with a faraway look. I ask how often she makes this flight. Once or twice a month. Does she enjoy Israel? Not much. She stays in a hotel in Tel Aviv. She goes to the beach. She flies back. What about Jerusalem? She has not been there. What is in Jerusalem?

The illustrated guidebook shows a medieval map of the world. The map is round. The sun has a beard of fire. All the rivers of the world spew from the mouth of the moon. At the center of the world is Jerusalem. (Robert Rodriguez, The God of the Desert, Harper’s Magazine)

One can’t help but be thinking of the displaced, of refugees fleeing strife, with the situation in Eastern Europe right now; and let’s be frank – not all refugees are ‘equal’ with race and geopolitics rearing their ugly heads, as we see in both the history and present of Canada, and the wider world. I’m not often a fan of Ai Weiwei, but his work about Alan Kurdi touched a nerve that many of us may not have known – or my still deny – was exposed.

In light of that unpleasant reality, the works of Larissa Sansour, a Palestinian born artist were on my mind this week, especially her series Nation Estate. Jerusalem is not a neutral place, or an unloaded term. It may be the best example in ‘Western’ nation states – though in the Middle East – of a place that is intensely contested, an apex of Salman Rushdie’s notion of an ‘imaginary homeland.’

Even that tepid taupe of Wikipedia offers this: Given the city’s central position in both Israeli nationalism and Palestinian nationalism, the selectivity required to summarize more than 6,000 years of inhabited history is often influenced by ideological bias or background (please see Historiography and nationalism).

“In her Nation Estate (2012) series, Sansour conceptualizes an immense high-rise as a new home for her people. In each digitally manipulated photograph in this series, she places herself on a different floor of the edifice. We see her travel from the main lobby, to the Dead Sea, to Gaza, all in the space of a single building.”

“….Nation Estate takes place…in a mammoth high-rise that houses the entirety of the Palestinian people in one easy-to-navigate complex. Blurring the lines between utopian and dystopian realities, she paints a seemingly peaceful, albeit unfathomably sterile future where walls cease to function as barriers to human interaction.

“In a way there’s something positive about ‘Nation Estate.’ There are no check points and people can visit one city from another just by the use of the elevators. It’s an easy life that questions progress in general. Certain things are becoming easier, yet this skyscraper environment is completely inorganic,” Sansour stated. “It’s actually really a mockery when you think about it — living in a skyscraper. So it’s completely dystopian in the end.” (from here)

Who is a ‘real’ refugee? Who has a ‘right’ to live in a space, and to claim that they ‘own’ the land? Sansour’s works have often addressed this; we live in a world where to be Palestinian is often dismissed as illegitimate, if even ‘legal’, whatever that might even mean. Perhaps, as alluded to in Sansour’s work, the idea of ownership and wealth not only preclude but define / deform what it means to be a citizen, or even to be human.

In looking at this work, I also cannot help but consider the lament of Psalm 137: For how are we to sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?

You can see more of her work at her site, and her Instagram is @larissasansour.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Put sunflower seeds in your pocket so they grow when you die | Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. 1889

February 26, 2022Put sunflower seeds in your pocket so they grow when you die | Van Gogh’s Sunflowers. 1889

It is an understatement to say that many of us have Ukraine in our thoughts, right now. Historians have commented that coverage of many past conflicts have been defined by technological advancements (such as Vietnam with television, or the first Persian Gulf conflict, with it’s almost video game style graphics); the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine has already become one that is being seen – and perhaps shaped – by the internet, with streaming and social media.

A recent exchange between a brave Ukrainian woman and Russian soldiers brought to mind the work we’re featuring here (Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers).

From The Guardian: “A woman is being hailed on social media after she confronted a heavily armed Russian soldier and offered him sunflower seeds – so that flowers would grow if he died there on Ukraine’s soil. ‘You’re occupants, you’re fascists,’ she shouts, standing about a metre from the soldier.”

She goes on to command them to “take these seeds and put them in your pockets so at least sunflowers will grow when you all lie down here.”

You can see the video of that interaction here.

If it seems a bit crass to cite Van Gogh here, it’s good to remember his work has become a symbol of hope against adversity, of beauty in the midst of pain and suffering, and – possibly – that there is more good than bad in the world. Or, perhaps, it’s more about defiance in the face of difficult odds, and how history – against our trepidations – can be an appropriate judge of contemporary events.

There’s a number of ways you can support the people of Ukraine here, and it’s worth noting that Canada has the world’s third-largest Ukrainian population, so our neighbours and friends are surely watching this with hope and fear. ~ Bart Gazzola & Mark Walton

Read More

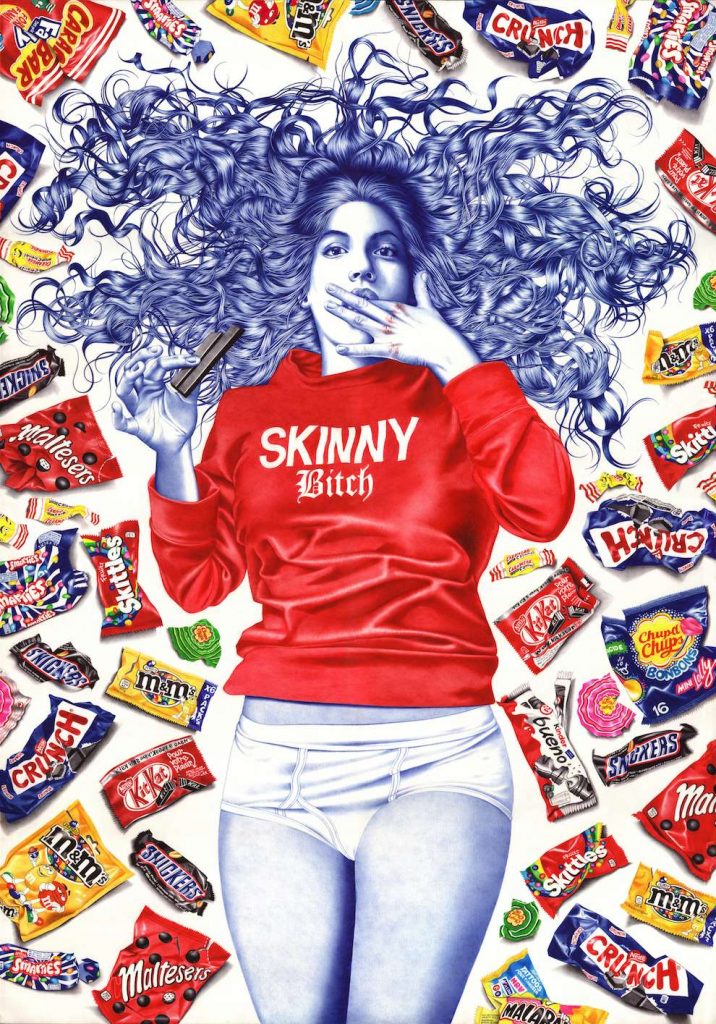

Mia | Helena Hauss, 2015

February 14, 2022Mia | Helena Hauss, 2015

One of my favourite scenes from the television series Sense8 is when one of the main characters is about to step into the ring, for an underground boxing match; a match between a male and female fighter – and the referee, in response to the man’s bravado, his arrogant assurance of his victory, is that “smart money’s on the skinny bitch.”

And the “smart money” turns out to be right.

Helena Hauss’ images are definitively feminist, but with a forceful humour that amuses and fractures a simplistic reading of her work. The aforementioned exchange came to mind due to the shirt worn by Hauss’ Mia, proudly proclaiming ‘skinny bitch’, as she reclines amidst tasty decadent snacks, not just unmindful of our judgement but meeting our gaze straight on, provocatively licking her fingers with eyes that make it clear she couldn’t give less of a fuck about what ‘we’ think.

Hauss works in ballpoint pen: her skill and discipline in this unusual format is awe inspiring, and there’s an audacity required in employing this medium that is matched by the vivacity and authenticity of the players in her tableaux. Whether in Mia’s unflinching stare, or the energy of The Fight or the impressive minutiae and detailed renderings of The Bet or The Sleepover, Helena Hauss is awesome in her medium.

Her words: My works all explore a same running theme of Irreverence : challenging an imposed decorum and reveling in one’s own pre-established labels rather than having to apologize for them.It’s about self-acceptance through self-deprecation and satire.

More of Helana Hauss’ work can be seen at her site, and her IG: @helenahauss.

She often shares videos of her process, which is lovely to enjoy as well.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments