In: curators pick

Rich-Joseph Facun | Little Cities | 2022

May 26, 2023Rich-Joseph Facun | Little Cities | 2022

…it takes an ocean of trust in the kingdom of rust…

(Doves)

The Cuyahoga River won’t kill you no more.

They cleaned it up back in ’74.

Well, you might get sick – but welcome to Ohio.

(Luke Doucet)

As I get older, there are some memories that still have an unexpected vivacity : and living again in the city and region where I grew up offers an odd looping of recollection, with elements of nostalgia – and the opposite of that, which might be cynicism or nihilism – informing and deforming my thoughts.

When I first encountered Rich – Joseph Facun’s images – specifically his Little Cities series – I felt transported back to my late teens and early twenties and shuttling back and forth between Windsor / Detroit and St. Catharines, seeing the underbelly of the rust belt wonderland. Specifically taking the train, and thus getting glimpses of smaller urban spaces across Southern Ontario that are often unseen or unconsidered, simply spaces to traverse on the way to somewhere else, not ‘valid’ to be ‘seen’ but as a space to be left behind or to be traversed with your mind – and destination elsewhere.

Facun’s scenes are part of a story that unfolds amidst the post-industrial United States – and these are spaces I’m familiar with from Niagara or the Windsor / Detroit region, that might be a ‘kingdom of rust’ or the ‘rust belt wonderland’ : a detritus of past ‘progress’, leavings of history that we might ignore or not acknowledge but that are literally part of the [memory of] landscape.

In Little Cities Rich-Joseph Facun “guides viewers on a meandering meditation through Southeastern Ohio by depicting the vernacular post-industrial landscape. In their quiet formality, the images call to mind past dreams, present disillusionment, and gently nudge us to look beyond what can be seen on the surface. Through recurring motifs, Facun excavates remaining signs of the Indigenous communities who once called this region home. In mankind’s hubris, we want to believe we shape the land we live on. Facun’s photographs remind us that the landscape contains memory, and it is witness to our misdeeds.” (from here)

Rich-Joseph Facun is a photographer of Indigenous Mexican and Filipino descent. His words : “His work aims to offer an authentic look into endangered, bygone, and fringe cultures—those transitions in time where places fade but people persist.

The exploration of place, community and cultural identity present themselves as a common denominator in both his life and photographic endeavors.

Before finding “home” in the Appalachian Foothills of southeast Ohio, Facun roamed the globe for 15 years working as a photojournalist. During that time he was sent on assignment to over a dozen countries, and for three of those years he was based in the United Arab Emirates.”

More of Facun’s work can be seen here and his IG is here. He has produced a publication for Little Cities, and I encourage you to spend some time with his Black Diamonds and 1804 series. Facun reminds me of Mary Ellen Mark‘s assertion as to how “photography is closest to writing, not painting. It’s closest to writing because you are using this machine to convey an idea. The image shouldn’t need a caption; it should already convey an idea.”

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Beth Galton | Aftermath

May 19, 2023Beth Galton | Aftermath

[Galton’s] photographs, created with the help of prop-stylist Bette Blau, investigate the consequences to reproductive health and freedom after the Supreme Court’s decision in June to overturn Roe v. Wade. Since then, information about how to give oneself an abortion has surged across social-media platforms. This is the sad, secret knowledge passed by rumor and word of mouth in the absence of safe and legal abortion care.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Among the Dutch still lifes, there is a subgenre known as vanitas paintings, which serve to remind the viewer of her mortality through not-so-subtle emblems such as clock faces, burning candles and human skulls. Galton, making visible the private horror of terminating a pregnancy without the protection of the law, performs the gesture even more literally. Her still lifes force us to contemplate the possibility of the mother’s unnecessary death.

(Dana Goodyear)

Dr. Savita Halappanavar’s needless death is where we will begin in considering Beth Galton’s images Aftermath : The Overturning of Roe V Wade.

Halappanavar (1981 – 2012) “was a dentist of Indian origin, living in Ireland, who died from sepsis after her request for an abortion was denied on legal grounds. In the wake of a nationwide outcry over her death, voters passed in a landslide the Thirty-Sixth Amendment of the Constitution, which repealed the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland and empowered the Oireachtas to legislate for abortion.” One might say that her gratuitously cruel death – which can be laid at the feet of the catholic church which for too long has denigrated justice in too many countries – galvanized the people of Ireland to a more humane and informed position.

If I may engage in a rude observation, it is notable when such a formerly staunch catholic country as Ireland can shed the barbarism of that cult to acknowledge the essential autonomous humanity of people. But perhaps the legacy of the Magdalene Laundries are clear in their minds….

Galton’s images are quiet : a superficial glance will not immediately reveal their truth, but these are as meticulously well executed as many of her more commercial works. But they are not initially recognizable for what they are, with their aesthetic acumen (or – perhaps more likely – as a man, I don’t recognize certain tools. Though I’m surely part of any intended audience, it is more so something I’m being taught rather than having a necessary yet unwanted familiarity with them….and that ignorance on my part is just a small piece of a leviathan of such willful ignorance of church and state in Galton’s country, and my own…).

In an article about this series here, notes are offered such as with Bodily Harm : “Bodily harm caused by wire hangers, knitting needles, douches and hard objects. Emblems from the nightmare past, in the spotlight of now.” Another – Back Alley Abortion – presents “objects traditionally used by medical professionals [that] are also used illegally to perform abortions. Also represented is the abortion pill, shipped to states where abortion is now illegal.”

Galtan is a citizen of the U.S., and this debate is raging there and – as happens with Canada – it’s spilling into our spaces, tainting any genuine informed debate with religious ignorance and outright lies and hypocrisy (I live in Niagara, where former ‘Bishop’ Wingle all but had a stroke when Dr. Henry Morgentaler was awarded the Order of Canada for his work in providing necessary health care. Wingle’s voracious hypocrisy only ceased when it was revealed that one of his ‘priests’ was a serial child molester, at which point he resigned, ran away and hid and the facts are still unclear on how much Wingle abetted or ignored. Do I truly need to ask why acolytes of this cult are being platformed regarding this issue, health care and so many others where their contribution is vile and ignorant?)

Galton’s works are subtle but have much to say : an award winning photographer who lives and works in New York City, Galton’s “images and short films tell stories – the story of memories, of what and how we eat together, a love of nature, and the pleasure of shared experiences.”

It’s also worth noting that the aesthetic discipline of Galton’s images – the beauty in horror, perhaps – is tempered by the facts of what she’s sharing.

Too often – which we’re seeing in Canada, right now – there’s intentional misrepresentation and outright lies around the issue (again, copying what happens south of us, where SCOTUS members lied outright about their intentions, and quote Medieval Witchfinders while bleating they are ‘moral’). Galton’s works remind us – those of us who never knew, choose not to know or hypocritically ignore – of facts : specifically that within the erroneously snivelling assertion of being ‘pro life’, that no such concern is shown – the opposite, in fact – for women.

More of this series can be seen here and Beth Galton’s site is here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Ralph Ziman | The Ghosts Project

May 12, 2023Ralph Ziman | The Ghosts Project

The total life of man is reflected in his art. And so when people come to us and say, “Why are you… you artists so political?” I don’t know what they are talking about. Because art is political. And further more I’d say this, that those who tell you “Do not put too much politics in your art,” are not being honest. If you look very carefully you will see that they are the same people who are quite happy with the situation as it is. And what they are saying is not don’t introduce politics. What they are saying is don’t upset the system. They are just as political as any of us. It’s only that they are on the other side. Now in my enthusiasm, art cannot be on the side of the oppressor.

(Chinua Achebe in conversation with James Baldwin, 1981)

The ghosts won’t starve, but we will perish.

(Paul Virilio)

Since approximately 2014, South African filmmaker and artist Ralph Ziman’s The Ghosts Project has been enacted in a number of nation states in Africa. In Ziman’s words: “Arms that are paid for and imported into Africa are being used by individuals not just for defense but often by corrupt, autocratic governments to oppress their own people. This body of work deals with the international arms trade and Africa, a trade that for the most part only goes in one direction — into Africa — and one that not only fuels, but also sustains conflict across the continent.”

One aspect of the project involved Ziman photographing “Zimbabwean street vendors wielding handmade replicas of AK-47s which are adorned in traditional Shona-style beading. The multimedia project aims to highlight the international arms trade and its devastating influence.

Another iteration of this performative hybrid of fine craft and photography – and also an intervention into public spaces – is as follows: “I had six Zimbabwean artists use traditional African beads and wire to manufacture several hundred replica bead/guns like AK-47s, as well as several replica bead/general purpose machine guns (GPMGs), along with the ammunition. In response to the guns sent into that culture, the mural represents an aesthetic, anti-lethal cultural response, a visual export out of Africa. And the bead/guns themselves, manufactured in Africa, are currently being shipped to the USA and Europe. This bead/arms project provided six months full-time work for half a dozen craftsman who got well deserved break from making wire animals for tourists.

The completed bead/guns were the subject of a photo-shoot in crime ridden downtown Johannesburg. The subjects were the artists who made the guns, several construction workers who happened to witness the shoot, and a member of the South African Police Services who just wanted his picture taken.” (from here)

Ralph Ziman was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, and currently lives and works in Los Angeles, California : “His practice is motivated by a sense of social responsibility toward global politics. Using imagery that is at once vivid and dark, he comments on serious issues such as life under apartheid, the arms trade and trophy hunting. His work extends across a variety of media, including film, photography, public intervention, sculpture, and installation.”

More of Ralph Ziman’s work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Dorothea Lange | A family of drought refugees from Abilene, Texas, on the road in California | 1936

May 4, 2023Dorothea Lange (1895 – 1965) | A family of drought refugees from Abilene, Texas, on the road in California | 1936

“The depression was making people disappear.

They vanished from factories and warehouses and workshops, the number of toilers halving, then halving again, until finally all were gone, the doors closed and padlocked, the buildings like tombs. They vanished from the lunchtime spots where they used to congregate, the diners and deli counters where they would grab coffee on the way in or a slice of pie on the way out.

They disappeared from the streets.

They were whisked from the apartments whose rents they couldn’t meet and carted out of the homes whose mortgages they couldn’t keep pace with, lending once thriving neighborhoods a desolate air, broken windows on porches and trash strewn across overgrown yards. They disappeared from the buses and streetcars, choosing to wear out their shoe leather rather than drop another dime down the driver’s metal bucket. They disappeared from shops and markets, because if you yourself could spend a few hours to build it, sew it, repair it, reline it, reshod it, reclod it, or reinvent it for some other purpose, you sure as hell weren’t going to buy a new one.

They disappeared from bedrooms, seeking solace where they could: a speakeasy, or, once the mistake of Prohibition had been corrected, a reopened tavern, or another woman’s arms—someone who might not have known their name and certainly didn’t know their faults well enough to judge them, someone who needed a laugh as badly as they did.

They disappeared, but never before your eyes; they never had that magic. It was like a shadow when the sun has set; you don’t notice the shadow’s absence because you expect it. But the next morning the sun rises, and the shadow’s still gone.”

(Thomas Mullen, The Many Deaths of the Firefly Brothers)

I have a tendency in my research to fall down rabbit holes: this is often shaped by history (my interest – which has manifested on this site – in post Soviet artists, for example) and of late The Great Depression has been a point of interest. My enjoyment of horror intersects here, so I will confess that I came to the author that I quote liberally above (whose book follows two brothers whom are bank robbers during the Great Depression, harshly factual and researched, but they find they are resurrected each time they’re killed in one of their robberies) through Daniel Knauf’s Carnivàle series. But, like another writer has pointed out, improbability and violence overflow from ordinary life, and the Great Depression was a time more, perhaps, malleable than most, as many assumptions were fractured irreparably…

And the horrors experienced by many from the Crash of 1929 through the Depression were ‘unimaginable’ to many, until they became commonplace, and now, it seems, have been forgotten. This is similar to how we forget that Lange’s subjects are not just icons but actual people who lived, suffered and died.

To many, Lange’s work requires no introduction. Many of her photographs are so stitched into the fabric of a communal history that they act as signifiers for collective memories. Nonetheless: Dorothea Lange “was an American documentary photographer and photojournalist, best known for her Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Lange’s photographs influenced the development of documentary photography and humanized the consequences of the Great Depression.” (from here)

I return to Mullen’s book that had flavours of horror, but not in the way I expected, as it was more historical than ‘supernatural’ horror:

“Ten feet behind them, standing at the base of an arc light and looking in the opposite direction, was a young, balding man who Weston supposed was the father. The man looked as if he were trying very hard to become invisible.

When you bump into an old acquaintance on the street, you ask him how he’s doing. He tells you a story and then you tell him your story, and both of you are trying to see where you fit within the other’s. Your story says: This is the way the world is, and I’m the center, over here. But if the other guy tells a different story, with the world like this, where the center’s actually over here, then you realize that you’re way off to the side.

This man did not need to be told he was off to the side. He clearly realized it.”

More of Lange’s work – both her iconic images of The Great Depression and her later work that was more local but considered the same issues of justice and equality – can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Kristina Varaksina | Self portrait wrapped, 2020

April 27, 2023Kristina Varaksina | Self portrait wrapped, from the Self Reflection series, 2020

“Why do men feel threatened by women?” I asked a male friend of mine. (I love that wonderful rhetorical device, “a male friend of mine.” It’s often used by female journalists when they want to say something particularly bitchy but don’t want to be held responsible for it themselves. It also lets people know that you do have male friends, that you aren’t one of those fire-breathing mythical monsters, The Radical Feminists, who walk around with little pairs of scissors and kick men in the shins if they open doors for you. “A male friend of mine” also gives — let us admit it — a certain weight to the opinions expressed.)

So this male friend of mine, who does by the way exist, conveniently entered into the following dialogue. “I mean,” I said, “men are bigger, most of the time, they can run faster, strangle better, and they have on the average a lot more money and power.” “They’re afraid women will laugh at them,” he said. “Undercut their world view.”

Then I asked some women students in a quickie poetry seminar I was giving, “Why do women feel threatened by men?” “They’re afraid of being killed,” they said.

(Margaret Atwood, Second Words: Selected Critical Prose, 1982)

Kristina Varaksina received her Master’s in Photography from the Academy of Art University, San Francisco, in 2013. Born in Russia, Varaksina has resided in the USA since 2010 and currently divides her time between London and New York.

From here: “In her personal work, Varaksina explores the vulnerabilities, insecurities and self-search of a woman and an artist. Her work is a creative response to what’s going on in the world and her immediate environment. Through visual symbolism, carefully curated colour palettes and cinematic lighting she reflects the strongest emotions she and her subjects experience.” I would inject another line from Atwood here, in response: I’m working on my own life story. I don’t mean I’m putting it together; no, I’m taking it apart.

Varaksina gives voice to women from different ethnic, socio-economic, and cultural backgrounds, each doing their best to accept themselves as who they are and be proud of that. Varaksina sees her job as a photographer to make “ordinary” women more visible and therefore, more valuable.”

Varaksina has earned numerous awards for her work: her figures alternate between an unflinching gaze that challenges – perhaps unnerves – the viewer, and a stillness where our presence is neither requested or needed, intruding into the quiet being of her subjects. The Self Reflection series – which is ongoing – has been described as both ‘claustrophobic’ and a commentary on the history of portraiture in the Western canon. In this body of work, her stare is direct and unrelenting, as she not only turns her camera on herself as part of her work about women but turns her gaze upon us, too.

More of her work can be seen here. Varaksina’s IG is @kristinavaraksina

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Scott Conary | Lamb on Paper, 2023

April 20, 2023Scott Conary | Lamb on Paper, 2023

Flesh is our indisputable commonality. Whatever our race, our religion, our politics we are faced every morning with the fact of our bodies. Their frailties, their demands, their desires. And yet the erotic appetites that spring from – and are expressed through – those bodies, are so often a source of bitter dissension and division. Acts that offer a glimpse of transcendence to one group are condemned by another. We are pressured from every side – by peers, by church, by state – to accept the consensual definition of taboo; though so often what excites our imaginations most is the violation of taboo. (Clive Barker)

Meat, weeds, eggs, bottles, and bones. What began as a way to get back to the basics of painting, without an agenda, became something else. The meat paintings are, understandably, the pieces that elicit the most questions. The first is usually, “Why meat?” The glib answer is “you can only paint so many pears.” The longer answer is that the meat is beautiful and somewhat evocative. We have a much more complicated reaction to a hunk of lamb than we do to pepper. The meat is the stuff of us. We are, after all, meat. The smell shifts while I work. The color changes. I have vivid memories of meals with family and friends built around meat. It’s beautiful, desirable, and it’s unclean. (Scott Conary)

At a very young age I encountered Alina Reyes’ novel Le Boucher [The Butcher] : consider that your only warning, before you proceed.

Let us talk about meat, about the way of all flesh, about the grotesque and evocative history of painters and photographers offering us a sense of the sensual and the shocking.

Ah, but before we get to that I must say that when I encountered Scott Conary’s work on one of my social media feeds, I was struck by it’s beauty and execution (I was unsurprised it’s painted in oils, as there’s a sensuality to that medium) and it sent me on a deeper exploration of his works.

His words also acknowledge that this choice of subject matter is neither new nor to be eschewed. Many artists have employed this trope to investigate or confront larger issues: Chaïm Soutine’s Carcass of Beef, or Rembrandt van Rijn’s Slaughtered Ox, function both as still lives – though I might use the French term of nature morte, here – but also as metaphors, whether for religion, suffering, violence or our own ongoing obsession and repulsion with our own physicality.

Conary’s renderings of meat and flesh – like many of the artists whose works I’ve shared in this post – are inappropriately beautiful.

But that beauty is tendered by how it is often metaphor, as well. One of the works I share below by Ilya Mashkov, considering the date of its execution during the Russian Civil War, is a commentary that evokes the words of his contemporary, Boris Pasternak, where his character Zhivago, speaking to the local commissar (after examining a dying man) sardonically avers that “It isn’t typhus. It’s another disease we don’t have in Moscow…starvation.” Andres Serrano‘s Cabeza de Vaca references a Spanish ‘explorer’, presented as plunder instead of plunderer, and Mark Ryden’s Meat Dress offers something for us to visually consume that explores some of the same ideas as Jana Sterbak’s Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic (which I’ve written about before) but in a more palatable form, perhaps.

Two more artists to share, that expand the conversation around Scott Conary’s meat works (I want to type that as one word – meatworks – as that seems more viscerally appropriate): Victoria Reynolds‘ art also offers “an uneasy tension between the understanding of flesh as food, and our self-identification of it; her conflation of desire, mortality, viscerality, and the survival instinct is a powerful source of aesthetic fascination.” Kanevsky, on the other hand, is primarily a figurative artist, as an American with heavy Eastern European influences. When you look at more of his work, and his preference for nudes, you may be forgiven for thinking that the work below is just painting the interior, instead of the exterior, of his ‘models’….

More of Scott Conary’s work can be seen here and his IG can be found here. His practice – and choice of subject matter – is quite varied (I was simply seduced by his meat works, if you will, but I did consider using his interpretations of eggs as a basis for a curator’s pick, as well) and worth exploring.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Geoff Farnsworth | Frank Auerbach, 2021

April 13, 2023Geoff Farnsworth | Frank Auerbach, 2021

But this rigour could be seen as revolutionary, one requiring a major historical shift from an art of representation to one of presence, that is, the direct experience of the object standing before you.

Julian Bell, What is Painting? Representation and Modern Art

Let us begin with a disclaimer that is, in fact, a compliment. I am not featuring my friend and the fine painter Geoff Farnsworth’s work because he has painted me twice (he has rendered, wonderfully, in paint, a number of denizens of Niagara), nor because the most recent of these is almost perfect in capturing the moment and conversation we were having (he snapped a picture at that time) and the vagaries of my overly expressive face and demeanor. I won’t tell you what we were discussing at the time (along the road in Welland) but my unimpressed face in that work tells you all you truly need to know, of the moment.

Farnsworth has demonstrated that ability on numerous occasions, to not only bring a telling likeness of his subjects into his paintings, but also to seemingly embed an element of their personality, too. A fine painter who dances between figurative works and hints of abstraction with an affinity for colour that defines his art.

His portraits seem to coalesce from his thick, mucoid paint, with a figure emerging from his rich colours and almost sculptural application of his medium. The image vascillates between abstraction and representation, and in this work – as it is a portrait of the painter Frank Auerbach – that dialogue happens not just on the canvas but in the conversation around the choice of subject, and Auerbach’s own ideas regarding non representational and more ‘realist’ painting. But – somewhat in opposition to this idea, as all these things blend together like paint on a surface – I’ll return to Julian Bell, whom I cited at the beginning of this essay: ‘ — there was no prior context to the painting itself. The viewer’s eyes would submit, and the painting would act.’

But let’s end by returning to Auerbach (from Frank Auerbach Speaking and Painting by Catherine Lampert): “Auerbach views such claims and labels as essentially meaningless; for him, where figurative art excels, if it is any good, is in what is abstract within the painting and concept. The forms one engages with, and invents, will have a plastic character and individuality unconnected to their names.”

Since I mentioned it in this article, I feel compelled to include an image of the fine portrait that Geoff Farnsworth painted of me, so you might have a visual to augment my words. But I will temper it with an image from Ad Reinhardt, whose ideas about the immediacy of the art object, and the necessity of its primacy in any interpretation of the same is relevant to considering Farnsworth’s portraits, which shift and flow and fracture and come together again, all in colour and line and very physical, goopy ways. Both of these can be seen in the proper post for this artist, not on this front page.

Geoff Farnsworth began his art training in Vancouver, B.C. at the Federation of Canadian Artists, Emily Carr, and Capilano College in the Graphic Design & Illustration Program. He moved to New York City to train at the Art Students League from 1997 to 2002. His paintings have been shown in New York City, Washington DC, Minneapolis, Toronto, Vancouver, Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Niagara Falls, Norway, Sweden, and Trinidad.

His words: “My paintings explore a relationship between figurative and abstraction in order to meld unconscious probing and stylistic innovation with a meditative figural base. It is important to me that the paintings work well as collections of shape, colour, texture, and energy, while also building a compelling image. Working with people and objects from my personal world, I focus on maintaining a balance between plan and accident, known and unknown, restraint and exuberance. My figures look out as much into mindscape as landscape.”

You can enjoy more of Farnsworth’s work here and more of his portrait works (of people both known and more local) can be viewed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Takayo Kiyota | Tama-Chan

April 6, 2023Takayo Kiyota | Tama-Chan

“That’s what you get for being food.”

― Margaret Atwood, The Edible Woman

Takayo Kiyota (also known as Tama-Chan) produces what can only be described as sushi art: some are playful, some are slightly more unsettling and others offer an interesting opportunity for dialogue about our relationship to food and larger assumptions around aesthetics.

In this artwork, Kiyota – who has interpreted famous works such as Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) or Vermeer’s Girl With A Pearl Earring | Meisje met de parel (1665) – re-imagines a painting that is well known but often misconstrued, sometimes in a bawdy manner.

Gabrielle d’Estrées et une de ses soeurs (Gabrielle d’Estrées and one of her sisters) was painted by an unknown artist (perhaps from the Fountainbleau School) around 1594. It can seen in the Louvre, in Paris: “The painting portrays Gabrielle d’Estrées, mistress of King Henry IV of France, sitting nude in a bath, holding a ring. Her sister Julienne-Hyppolite-Joséphine sits nude beside her and pinches d’Estrées’ right nipple.” More about this painting can be seen here.

Years ago, I experienced an audio environment / installation by Anitra Hamilton: the bare gallery space was inundated by two conflicting yet connected audible narratives. One section of the gallery was suffused by a recording of a Sotheby’s auction of artworks. The other was a cattle auction, with ‘prize’ animals going to the highest bidder. In a response to that exhibition I made some uncomfortable analogies to what we consume, how we value it, and the conversations around these things that ‘feed’ us.

Tama-chan (Takayo Kiyota) was born in Shinjuku, Tokyo. After graduating from the Setsu Mode Seminar she started to work in advertisement, magazines, and books as a freelance illustrator. Since 2005, she has called herself the sushi roll artist “Tama-chan.” Through workshops she has been introducing the importance of food culture, food education, as well as the joy of making things with her maki-sushi. In 2013, she won the second prize on “the longest scream in the world” sponsored by Innovation Norway. In 2014, Little More Co. published Smiling Sushi Roll, the first anthology of her work.

You can see more of these delicate and temporary artworks on IG : @smilingsushiroll39

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Pat Douthwaite | Bernard Berenson at Leptis Magna, 1966

March 31, 2023Pat Douthwaite | Bernard Berenson at Leptis Magna, 1966

I am only a picture-taster, the way others are wine – or tea – tasters.

Bernard Berenson

Years ago when I was on a panel talking about ‘modernism’ I offered a line from Clement Greenberg, that is one of my favourites (not solely for the idea expressed, but also as it seemed to fly in the face of many of the karaoke modernists who attended that discussion on the prairies who are sure ‘art’ ended with hard edged painting several decades ago): that we evaluate artwork with the criteria we have now, but fully understanding that this criteria can and must change.

Greenberg is one of the ‘old gods’ of the Western art canon – like Bernard Berenson, the erstwhile subject of this painting by Douthwaite. The site that Berenson is ‘visiting’ in this painting is of significant archeological important (more on that can be read here). Berenson (1865 – 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance, but his influence was much more than that, and he is one of the shoals of Western art history that is to be negotiated.

But – in deference to contested narratives, and considering how Douthwaite has, like too many female artists, not garnered the acclaim of some of her male colleagues – I also offer Atwood’s iconic line: “We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom. We lived in the gaps between the stories.” Douthwaite’s paintings have a striking originality, and though she’s often compared to Chaïm Soutine he is also – like Douthwaite – an artist whose work is immediately recognizable. This painting has a carnivalesque quality to it, and the ‘skulls’ suggest a merry dance of death…. she often “referred to herself as the “high priestess of the grotesque”, aptly describing her dedication to the arresting, often haunting, figurative work that carved out her place within British postwar art…[Douthwaite] was a distinctive and complex artist rather than [simply] a “difficult” woman, as she was sometimes described.” (from here)

Douthwaite’s approach is unique: ‘Instead of the traditional easel set up, Douthwaite preferred to paint on the floor: ‘I crawl around the floor on my knees, with a butcher’s apron round me, moving from drawing to drawing or canvas to canvas.’ She was unconventional in her painting technique too and rather than use brushes she worked the images up from the surface of the canvas using paint-soaked rags. She often depicts death with humour as if to underline the absurdity of life.’ (from here)

Pat Douthwaite was born in Glasgow in 1939 and initially studied mime and modern dance with Margaret Morris. She is primarily self taught, though in 1958 Pat lived in Suffolk with a group of painters. From 1959 to 1988 she travelled widely (North Africa, India, Peru, Venezuela, Europe, USA, Kashmir, Nepal, Pakistan, Ecuador) and from 1969 lived part of the time in Majorca. Douthwaite exhibited with the Women’s International Art Club in London between 1960 and 1966. She returned to spend the rest of her life in Scotland, passing away in 2002 at Dundee. In 2005 the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh mounted a memorial exhibition to mark her life and work.

Much more of her work can be seen here, and more about her life can be learned here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

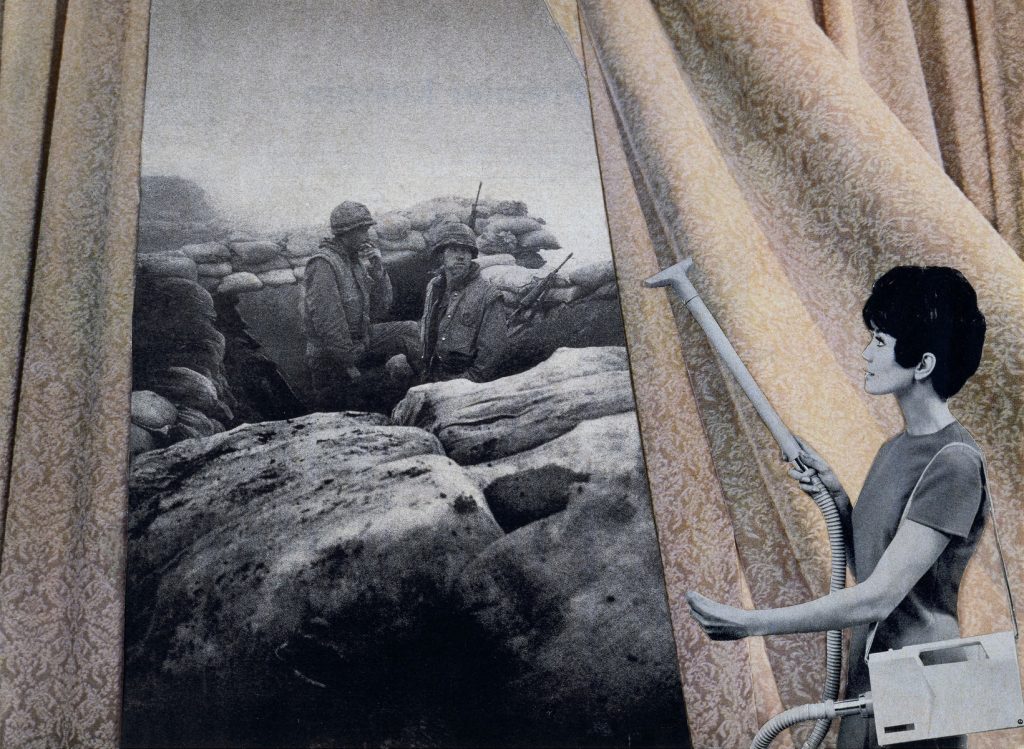

Martha Rosler | House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–1972

March 24, 2023Martha Rosler | House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–1972

Cotton’s generation grew up with a war in the house. For them, games of cops and robbers and cowboys and Indians no longer satisfied the senses. A boy had but to turn a control to be totally involved in the violent distension of experience that was Vietnam on television. Cotton became addicted to it. Vietnam was even a portable war.

A boy had but to move his personal set to have air strikes in the living room, search-and-destroy operations in the bedroom, naval bombardment in the bathroom—napalm before school, body bags before dinner.

(Glendon Swarthout, Bless the Beasts and the Children)

I recently read The Sacred Lies of Minnow Bly by Stephanie Oakes. The premise – of a young woman who survives a doomsday cult – sent me down a rabbit hole, if you will, of research on these cults, and since then I’ve been devouring a number of texts on the topic.

One of these – Jeffrey Melnick, Charles Manson’s Creepy Crawl: The Many Lives of America’s Most Infamous Family – offers an interesting supposition. Melnick argues that the Tate – LaBianca murders were used by many on the right – Nixon, for example – as a means by which to shutter debate about the (even then) failure of the nuclear family in the United States. This is similar to Zizek’s comment that most conversations about socialism always have a chicken little proclaiming it ‘will end in the gulag!’. Other societal issues are cast in a different light from the Manson murders, as well (for example, Melnick talks about the dismissive attitude towards runaways – especially girls – at that time, criminalizing or infantilizing them, using several of the Manson ‘family’ as examples, instead of focusing on larger issues within society).

Melnick dismisses with derision the idea that Manson ‘ended’ the supposed utopic dream of the 1960s – and for this post, a point he makes stays with me. Bluntly, that the violence of the Manson family was nary a drop in the bucket to the televised, sanctioned and officially endorsed violence of the war in Vietnam and other societal pressures. His words: “If the countercultural fabric got torn it was not because a few celebrities were killed in August of 1969. We would be better off attending to the plight of returning veterans, the not unconnected influx of harder drugs into American cities, the ongoing runaway crisis, and a major effort by the dominant culture—from the president on down—to repudiate and abandon young people and their culture.”

And this brings us to Martha Rosler’s series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–72.

The initial incarnation of this series was about Vietnam: in a despairing commentary about history Rosler would revisit and reinterpret it decades later, for the ‘war against terror’ in Iraq and Afghanistan…..

Rosler – in the tradition of artists like Hannah Höch – employs collage, using images that are familiar to us in tandem with others that fracture and trouble the original ‘homes’ on display. These might ‘homes’ in the literal sense, but also the ideologies and assumptions that inform those spaces, sometimes so implicitly that to highlight them engenders a denial of them, like a fish unaware of water as it’s so ubiquitous.

‘This work is one of twenty pieces from Rosler’s House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (c.1967-72) series created during, and influenced by, the Vietnam War. It was the first war in history that was literally brought into the homes of American people through the revolutionary new television set from which its horrors could be witnessed daily. It was often described as a “living room war” – a description loaded with strange poignancy as it shined a light on the eeriness of a nation living their everyday lives, ripe with consumerist concerns like keeping the stylish home drapes clean, all the while gruesome political realities took place elsewhere, becoming just another form of nightly entertainment in front of the tube.

Simultaneously, there is a feminist element to the work as it comments on the robotic mundaneness of female domestic work in the midst of global unrest. The idea of women striving to keep the house beautiful while war’s tragedies are omnipresent becomes almost comical, and presents a surreal picture about what we deem important. Recognizing the potential for manipulation in the photographic medium, Rosler once stated, “Any familiarity with photographic history shows that manipulation is integral to photography.”’ (from here)

More of Rosler’s extensive practice – and her roles as social critic and historian for more than half a century – can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments