In: painting

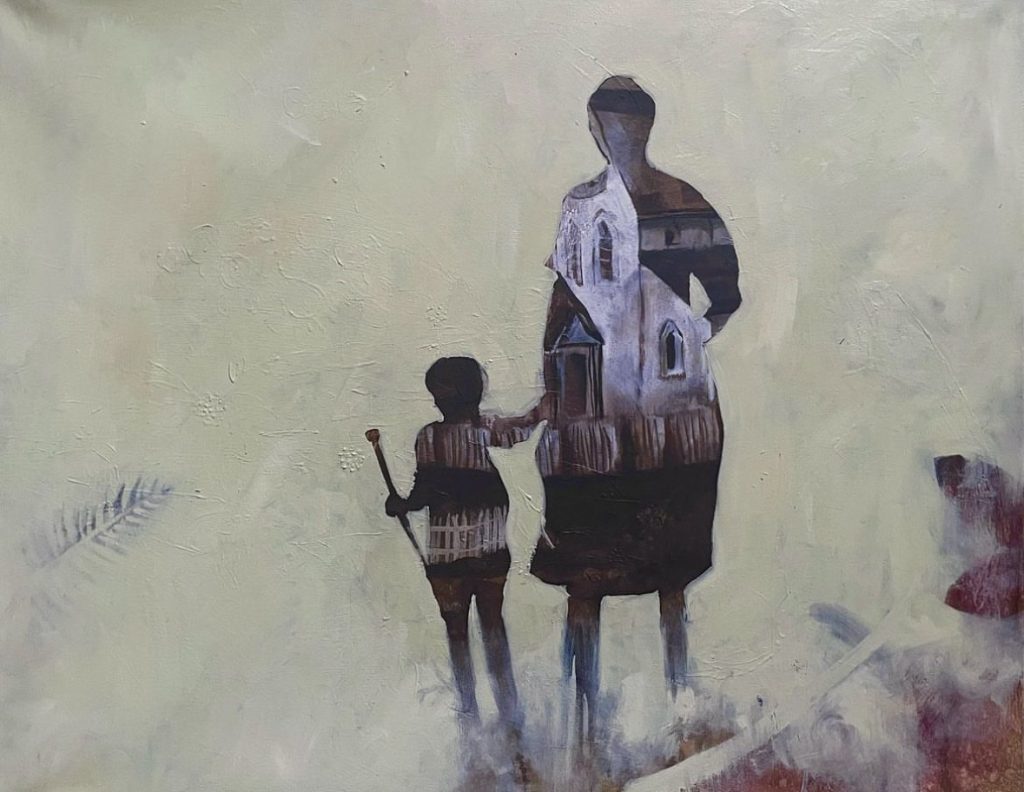

Curtis Doherty | Who Knit Ya? | 2024

February 25, 2024Curtis Doherty | Who Knit Ya? | 2024

February 20th to March 9th 2024 at Westland Gallery, London, Ontario

Out of these you make what you can, knowing that one thing leads to another. Sometime, someone will forget himself and say too much or else the corner of a picture will reveal the whole.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I am alive in everything I touch. Touch these pages and you have me in your fingertips. We survive in one another. Everything lives forever. Believe it. Nothing dies.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As the past moves under your fingertips, part of it crumbles. Other parts, you know you’ll never find. This is what you have.

(Timothy Findley, The Wars)

Mining family history in terms of artmaking is both a rich and a dangerous field. On this front, Amy Friends’ exhibition Assorted Boxes of Ordinary Life is a touchstone for me. In her exhibition, the assemblage – the editing, as to what might be revealed – of inherited objects that had significance that might be discerned by a visitor (others of which were opaque to an outsider) and the works that they inspired had a universal appeal. I say this as someone who has been exploring their ancestry in Niagara and found out some things that are also problematic (United Empire Loyalists as ancestors did not please me, ahem. I was comfortable with dissidents and criminals). Perhaps more of the ruminations of Timothy Findley is apropos here : “The occupants of memory have to be protected from strangers.”

In that same manner, Doherty presents a personal story that resonates with many of us, on many levels. Due to the locale – the sites he’s revisiting in paint being referential to Newfoundland, and the diaspora that has often been an experience of the people there, seeking work and economic stability far from home – the works of the late David Blackwood also come to mind, as an expansion of the conversation. One might see Blackwood’s works as one chapter of a story about Newfoundland, and Doherty’s as an addendum, decades later, but of the same ‘families.’

The artist statement :

“In 1930 a one-legged woman gathered all she had into a raggedy old chest and left Newfoundland for Quebec with her 6 year old son. Armfuls of photos, documents, and objects [lay] there for a century. What you are about to see is all of this brought to light [and] brought to life.

Witness the reality of the boy and his one-legged mother navigate the harsh landscape and time, the abandonment from the father, and the beauty of The Rock. The tangible and the intangible collide with areas of flat colour [so you must look] under the ribs of the wooden chest, to see the heart that lay under the ribs of the living chests.

“Who Knit Ya?” is a common Newfoundland term that asks who one’s parents are – a question this young boy asked his whole life. It begs to ask who we really are, and what legacy will we leave? It would be beyond folklore for anyone depicted here to imagine themselves captured in artworks a century later, and [moreso] what their toil paid forward. So as you view this work, be inspired to acknowledge the fact that we are just the tip of a larger iceberg, in a larger historical story. Ask yourself with introspection: WHO KNIT YA?”

I spoke to Doherty about his paintings (this new chapter added to family lore) after the reception for the exhibition, when conversations about the works led to wider considerations about the series. The words of the artist in conversation :

“It is a family story of mine…the small boy in the paintings is my grandfather, whose mother was the one legged woman, and whose father abandoned them.

There is also depictions of the mother’s parents (The Seal Hunter being her father- my great great grandfather). Through receiving this old trunk from my grandmother and all it’s neglected artifacts from 1880-1930, I’ve been able to piece together some family history, tell their story, and bring it to life from everything I found within that trunk. That was the trunk they moved to Quebec from Newfoundland with in 1929 / 30.

There are a few themes I’m touching on…stories of broken families, reconciliation of that brokenness, and lack of privilege and opportunity my grandfather had and [yet] still overcame it…And also just paying homage to hard working people of the past and the [amazing] thought [that] they could have never imagined they’d be depicted [and celebrated] in the future.”

In engaging with Doherty’s paintings, I’ve found myself looking through the lens of (appropriately) Canadian authors like Timothy Findley or Margaret Laurence whose characters are trying to make sense or discern a larger pattern of both their experiences or events that have defined their lives. This mirrors Doherty’s impetus for his paintings, and how sometimes the fragments are pushed together in a way that might not match the ‘reality’ but speak a contemporary truth to the descendants and inheritors of these objects and memories….

Now I am rampant with memory laments Hagar Shipley (from Margaret Laurence’s The Stone Angel) as in the declining days of her long existence she looks back on her life, in flashes both more intense and ‘real’ than her current state and often suffused with emotions both joyful and despairing. In some ways, she’s trying to reconcile conflicting and contested elements of a difficult story, just as we see in Doherty’s paintings, with his own family.

Doherty’s exhibition Who Knit Ya? – which the artist has subtitled ‘a vibrant exploration through a forgotten “new found land”‘ – is on view until March 9th, 2024 at Westland Gallery, London, Ontario. It’s presented in tandem with another exhibition titled Tales from the Rock (a group show of artists inspired by Newfoundland). I’ve relied heavily on literary references here in speaking to Doherty’s exhibition – and why not? It’s the stories we tell ourselves, or modify, as seen in Doherty’s paintings that define us. This is true even in the title of the show being a question that asks for similar stories from the viewers themselves : consider your lineage, and the people who defined and deformed you. Perhaps you see yourself as the latest link in a chain, or a break, instead.

Thus I am also comfortable to suggest you seek out David French’s play Leaving Home. It was one of the first stories I consumed, as a young man, about Newfoundland (though it takes place in Ontario – another parallel to Doherty’s paintings) that was not pure sentimentality but real and unflinching and difficult.

Although I have approached Doherty’s work while standing in the sphere of literature, I would indicate that when you look at his painting, that visual art has a significant advantage when exploring familial spaces with the inherent entanglements and contradictions: the multiplicity of interpretation, the possibility for injecting your own experiences into the works, is more rampant and possible. There is a vagueness – a subjectivity – to visual narratives that aligns with the vagaries of family history. The manner in which figures overlap and are constructed by other characters in the story acts as a visual depiction of how they are ‘knit’ from their ancestors. Some figures are just shadows in the background : and painting is the creation of a moment moreso than how photography is capturing one, and that is instrumental in what is presented here, which is perhaps dependent on facts but is also more demonstrative of feelings.

From his site : “Curtis Doherty is a Canadian painter who works primarily in oil who currently resides in Ontario. His work explores themes of history and the modern world through the complex relationship of the tangible and the intangible. He has studied at Sheridan College of Art & Design and abroad, as well as teaching at all levels.”

More of his work can be seen here.

The header image for this essay is titled Shule from the Scut : the images shared here are just a few selections from this series and were all created between 2019 and 2024. The full body of work can be enjoyed here.

Who Knit Ya? is on view at Westland Gallery (in London, Ontario) until the 9th of March 2024.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Joseba Sánchez Zabaleta | Room With Mirror

September 8, 2023Joseba Sánchez Zabaleta | Room With Mirror

“It is said that scattered through Despair’s domain are a multitude of tiny windows, hanging in the void. Each window looks out onto a different scene, being, in our world, a mirror. Sometimes you will look into a mirror and feel the eyes of Despair upon you, feel her hook catch and snag on your heart.

—————————————

In her world, there are so many windows. Each opening shows her an existence that’s fallen to her — some only for moments, some for lifetimes.”

(Neil Gaiman, from Season of Mists and Brief Lives, respectively)

Part of a larger series that engages with ‘footprints and memory’ and places now empty where the artist has recorded – or interpreted – the detritus of those who once existed in these spaces, Zabaleta’s paintings seem haunted. Though empty of people, their presences still suffuse the space, with an implication of absence, with someone missing that still is intrinsic to the atmosphere of his compositions.

His words : I wanted to paint the uninhabited buildings that I found in search of the memory of all those lives that I sensed should remain intact and detained in them. Waiting for something to happen, the empty buildings keep within their walls the trace of what has been lived between them. Somehow the fled love is imprinted on the plaster of its partitions. The silence of those deaf rooms falls through the walls, depositing itself between the joints in the pavement, next to the arid and dusty trace of time, among accumulated fragments, piled up by the wind in the corners.

One of the images I’ve shared in the full post is titled Marlom. Zabaleta offers the following meditation about this site, this painting, and the unknown person :

Of you there is only a name written in blue blood.

You thought it would be easy, that it would be just as they had told you. You thought that if others had achieved it, you would also achieve it. You thought while you were hiding, while the world was chasing you, what would be the best way not to be seen, to disappear, and you didn’t realize that nobody saw you, that you could have gone out on the road and walked, because those who are like you around here and you don’t look at them nor do you see them.

More of Joseba Sánchez Zabaleta’s fine paintings can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Scott Conary | Lamb on Paper, 2023

April 20, 2023Scott Conary | Lamb on Paper, 2023

Flesh is our indisputable commonality. Whatever our race, our religion, our politics we are faced every morning with the fact of our bodies. Their frailties, their demands, their desires. And yet the erotic appetites that spring from – and are expressed through – those bodies, are so often a source of bitter dissension and division. Acts that offer a glimpse of transcendence to one group are condemned by another. We are pressured from every side – by peers, by church, by state – to accept the consensual definition of taboo; though so often what excites our imaginations most is the violation of taboo. (Clive Barker)

Meat, weeds, eggs, bottles, and bones. What began as a way to get back to the basics of painting, without an agenda, became something else. The meat paintings are, understandably, the pieces that elicit the most questions. The first is usually, “Why meat?” The glib answer is “you can only paint so many pears.” The longer answer is that the meat is beautiful and somewhat evocative. We have a much more complicated reaction to a hunk of lamb than we do to pepper. The meat is the stuff of us. We are, after all, meat. The smell shifts while I work. The color changes. I have vivid memories of meals with family and friends built around meat. It’s beautiful, desirable, and it’s unclean. (Scott Conary)

At a very young age I encountered Alina Reyes’ novel Le Boucher [The Butcher] : consider that your only warning, before you proceed.

Let us talk about meat, about the way of all flesh, about the grotesque and evocative history of painters and photographers offering us a sense of the sensual and the shocking.

Ah, but before we get to that I must say that when I encountered Scott Conary’s work on one of my social media feeds, I was struck by it’s beauty and execution (I was unsurprised it’s painted in oils, as there’s a sensuality to that medium) and it sent me on a deeper exploration of his works.

His words also acknowledge that this choice of subject matter is neither new nor to be eschewed. Many artists have employed this trope to investigate or confront larger issues: Chaïm Soutine’s Carcass of Beef, or Rembrandt van Rijn’s Slaughtered Ox, function both as still lives – though I might use the French term of nature morte, here – but also as metaphors, whether for religion, suffering, violence or our own ongoing obsession and repulsion with our own physicality.

Conary’s renderings of meat and flesh – like many of the artists whose works I’ve shared in this post – are inappropriately beautiful.

But that beauty is tendered by how it is often metaphor, as well. One of the works I share below by Ilya Mashkov, considering the date of its execution during the Russian Civil War, is a commentary that evokes the words of his contemporary, Boris Pasternak, where his character Zhivago, speaking to the local commissar (after examining a dying man) sardonically avers that “It isn’t typhus. It’s another disease we don’t have in Moscow…starvation.” Andres Serrano‘s Cabeza de Vaca references a Spanish ‘explorer’, presented as plunder instead of plunderer, and Mark Ryden’s Meat Dress offers something for us to visually consume that explores some of the same ideas as Jana Sterbak’s Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic (which I’ve written about before) but in a more palatable form, perhaps.

Two more artists to share, that expand the conversation around Scott Conary’s meat works (I want to type that as one word – meatworks – as that seems more viscerally appropriate): Victoria Reynolds‘ art also offers “an uneasy tension between the understanding of flesh as food, and our self-identification of it; her conflation of desire, mortality, viscerality, and the survival instinct is a powerful source of aesthetic fascination.” Kanevsky, on the other hand, is primarily a figurative artist, as an American with heavy Eastern European influences. When you look at more of his work, and his preference for nudes, you may be forgiven for thinking that the work below is just painting the interior, instead of the exterior, of his ‘models’….

More of Scott Conary’s work can be seen here and his IG can be found here. His practice – and choice of subject matter – is quite varied (I was simply seduced by his meat works, if you will, but I did consider using his interpretations of eggs as a basis for a curator’s pick, as well) and worth exploring.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Geoff Farnsworth | Frank Auerbach, 2021

April 13, 2023Geoff Farnsworth | Frank Auerbach, 2021

But this rigour could be seen as revolutionary, one requiring a major historical shift from an art of representation to one of presence, that is, the direct experience of the object standing before you.

Julian Bell, What is Painting? Representation and Modern Art

Let us begin with a disclaimer that is, in fact, a compliment. I am not featuring my friend and the fine painter Geoff Farnsworth’s work because he has painted me twice (he has rendered, wonderfully, in paint, a number of denizens of Niagara), nor because the most recent of these is almost perfect in capturing the moment and conversation we were having (he snapped a picture at that time) and the vagaries of my overly expressive face and demeanor. I won’t tell you what we were discussing at the time (along the road in Welland) but my unimpressed face in that work tells you all you truly need to know, of the moment.

Farnsworth has demonstrated that ability on numerous occasions, to not only bring a telling likeness of his subjects into his paintings, but also to seemingly embed an element of their personality, too. A fine painter who dances between figurative works and hints of abstraction with an affinity for colour that defines his art.

His portraits seem to coalesce from his thick, mucoid paint, with a figure emerging from his rich colours and almost sculptural application of his medium. The image vascillates between abstraction and representation, and in this work – as it is a portrait of the painter Frank Auerbach – that dialogue happens not just on the canvas but in the conversation around the choice of subject, and Auerbach’s own ideas regarding non representational and more ‘realist’ painting. But – somewhat in opposition to this idea, as all these things blend together like paint on a surface – I’ll return to Julian Bell, whom I cited at the beginning of this essay: ‘ — there was no prior context to the painting itself. The viewer’s eyes would submit, and the painting would act.’

But let’s end by returning to Auerbach (from Frank Auerbach Speaking and Painting by Catherine Lampert): “Auerbach views such claims and labels as essentially meaningless; for him, where figurative art excels, if it is any good, is in what is abstract within the painting and concept. The forms one engages with, and invents, will have a plastic character and individuality unconnected to their names.”

Since I mentioned it in this article, I feel compelled to include an image of the fine portrait that Geoff Farnsworth painted of me, so you might have a visual to augment my words. But I will temper it with an image from Ad Reinhardt, whose ideas about the immediacy of the art object, and the necessity of its primacy in any interpretation of the same is relevant to considering Farnsworth’s portraits, which shift and flow and fracture and come together again, all in colour and line and very physical, goopy ways. Both of these can be seen in the proper post for this artist, not on this front page.

Geoff Farnsworth began his art training in Vancouver, B.C. at the Federation of Canadian Artists, Emily Carr, and Capilano College in the Graphic Design & Illustration Program. He moved to New York City to train at the Art Students League from 1997 to 2002. His paintings have been shown in New York City, Washington DC, Minneapolis, Toronto, Vancouver, Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Niagara Falls, Norway, Sweden, and Trinidad.

His words: “My paintings explore a relationship between figurative and abstraction in order to meld unconscious probing and stylistic innovation with a meditative figural base. It is important to me that the paintings work well as collections of shape, colour, texture, and energy, while also building a compelling image. Working with people and objects from my personal world, I focus on maintaining a balance between plan and accident, known and unknown, restraint and exuberance. My figures look out as much into mindscape as landscape.”

You can enjoy more of Farnsworth’s work here and more of his portrait works (of people both known and more local) can be viewed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Pat Douthwaite | Bernard Berenson at Leptis Magna, 1966

March 31, 2023Pat Douthwaite | Bernard Berenson at Leptis Magna, 1966

I am only a picture-taster, the way others are wine – or tea – tasters.

Bernard Berenson

Years ago when I was on a panel talking about ‘modernism’ I offered a line from Clement Greenberg, that is one of my favourites (not solely for the idea expressed, but also as it seemed to fly in the face of many of the karaoke modernists who attended that discussion on the prairies who are sure ‘art’ ended with hard edged painting several decades ago): that we evaluate artwork with the criteria we have now, but fully understanding that this criteria can and must change.

Greenberg is one of the ‘old gods’ of the Western art canon – like Bernard Berenson, the erstwhile subject of this painting by Douthwaite. The site that Berenson is ‘visiting’ in this painting is of significant archeological important (more on that can be read here). Berenson (1865 – 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance, but his influence was much more than that, and he is one of the shoals of Western art history that is to be negotiated.

But – in deference to contested narratives, and considering how Douthwaite has, like too many female artists, not garnered the acclaim of some of her male colleagues – I also offer Atwood’s iconic line: “We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom. We lived in the gaps between the stories.” Douthwaite’s paintings have a striking originality, and though she’s often compared to Chaïm Soutine he is also – like Douthwaite – an artist whose work is immediately recognizable. This painting has a carnivalesque quality to it, and the ‘skulls’ suggest a merry dance of death…. she often “referred to herself as the “high priestess of the grotesque”, aptly describing her dedication to the arresting, often haunting, figurative work that carved out her place within British postwar art…[Douthwaite] was a distinctive and complex artist rather than [simply] a “difficult” woman, as she was sometimes described.” (from here)

Douthwaite’s approach is unique: ‘Instead of the traditional easel set up, Douthwaite preferred to paint on the floor: ‘I crawl around the floor on my knees, with a butcher’s apron round me, moving from drawing to drawing or canvas to canvas.’ She was unconventional in her painting technique too and rather than use brushes she worked the images up from the surface of the canvas using paint-soaked rags. She often depicts death with humour as if to underline the absurdity of life.’ (from here)

Pat Douthwaite was born in Glasgow in 1939 and initially studied mime and modern dance with Margaret Morris. She is primarily self taught, though in 1958 Pat lived in Suffolk with a group of painters. From 1959 to 1988 she travelled widely (North Africa, India, Peru, Venezuela, Europe, USA, Kashmir, Nepal, Pakistan, Ecuador) and from 1969 lived part of the time in Majorca. Douthwaite exhibited with the Women’s International Art Club in London between 1960 and 1966. She returned to spend the rest of her life in Scotland, passing away in 2002 at Dundee. In 2005 the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh mounted a memorial exhibition to mark her life and work.

Much more of her work can be seen here, and more about her life can be learned here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Shani Rhys James | Woman Smoking, 2011

March 7, 2023Shani Rhys James | Woman Smoking, 2011

“If painting doesn’t offer a way to dream and create emotions, then it’s not worth it.” (Pierre Soulages)

“Through the dialogue between paint and word, issues of domesticity, rootlessness and the relationship between women and the home will arise within the claustrophobic space, revealing how the places in which we live can say so much about who we are.” (Karen Price, from here)

There is a directness to James’ paintings – her moments that are both captured and created – of everyday, potentially ordinary scenes that is belied by her facility in paint. The physicality of the medium as employed by James’ is reminiscent of Lucian Freud (“She lathers and slathers on the paint with a kind of unrestrained glee” asserts Michael Glover), and the charged nature of what she presents to us is of the same ilk. Something has just happened, or is about to happen: there’s a quietus here, portentous and mildly unnerving.

The tight compositions of figures in rooms that seem suffocating were also a factor in the many works that James made about life during COVID lockdowns: “The claustrophobia of the interior is a metaphor for that frustration of being unable to express deep feelings of creativity, or to be involved in pertinent worldly issues.”

James also offers – not about this painting specifically, but applicable here that “my over-scaling of flowers [in the wallpaper] evokes either a cloying or menacing atmosphere, both repellent and seductive.” (from here)

Shani Rhys James is originally from Australia, but has lived and worked in Wales for since 1984. A more complete history can be read here.

If I may inject a touch of subjectivity, with the disclaimer that my mind often goes to dark places: when looking upon James’ people, I was reminded of an exchange in Margaret Laurence’s The Diviners, where the painter Dan McRaith finally shares some of his work with the main character Morag Dunn. McRaith figures, in the Gunn’s initial response, have ‘eyes [that] seem distanced, distorted–no, not distorted; the flesh mirrors the spirit’s pain, a greater pain than the flesh even if burned could feel. A grotesquerie of a woman, ragged plaid-shawled, eyes only unbelieving empty sockets, mouth open in a soundless cry that might never end, and in the background, a burning croft. Morag turns and looks at him, after looking at this last painting. “The dispossessed.”’

“Shani Rhys James is arguably the most exciting and successful Welsh painter of her generation. Her considerable reputation, both in Wales and beyond, continues to grow apace. She has exhibited with Martin Tinney Gallery since 1993 and subsequently her work has appeared in exhibitions throughout Britain and mainland Europe. William Packer, the distinguished art critic, has spoken of her as a painter of remarkable power, whose paintings are as convincing as anything currently being produced in Britain.” (from here, where you can see more of her fine works and learn about her many accomplishments)

Shani Rhys James’ site is here. She can be found on IG here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Bison Greeting (detail from Wildlife) | Sunaura Taylor, 2014

February 10, 2023Bison Greeting (detail from Wildlife) | Sunaura Taylor, 2014

“And you took the patronizing tone of an animal-trainer. Have you any idea what it is like to be spoken to in the way people speak to animals? A fascinating experience. Gives you quite a new feeling about animals. They don’t know words, but they understand tones. The tone people usually use to animals is affectionate, but it has an undertone of ‘What a fool you are!’ I suppose an animal has to make up its mind whether it will put up with that nonsense for the food and shelter that goes with it, or show the speaker who’s boss. That’s what I did.”

(Robertson Davies, World of Wonders)

I was introduced to Sunaura Taylor’s artwork by a friend who is a minister, and whose ministry is often focused upon the vulnerable in our Niagara community. We often share artists that interest us back and forth, as my own knowledge of contemporary religious painters appeals to her more progressive sensibilities. This image has a specific resonance to me. After spending so much time on the Canadian prairie the history of the use and abuse of the buffalo – and ideas now that tie buffalos metaphorically to different ways of thinking about society and our actions within it (through an Indigenous lens) with an aim to being ‘better’ and more inclusive as citizens within nations states – are factors in looking at Taylor’s painting.

Taylor’s visual art is striking, offering narratives that are both personal and offer a wider commentary on contemporary society. She is the recipient of a 2008 Joan Mitchell Foundation Award.

Her words: “My paintings are not at all only about the body, but the body is inevitably an aspect of my relationship with whatever it is that I am seeing.”

More: “I also want to paint and see politics, because I was born into them. I have a rare congenital disability called Arthrogryposis that was caused by toxic waste contamination in our groundwater, from the world’s largest polluter, the US military. I use a wheelchair for mobility and my mouth to paint. I grew up in a household of artists and anti-war activists, which perhaps made the knowledge that my body was formed by the industry of war, even more traumatic. I began at twelve to express myself and deal with these emotions through paint.”

Both quotes are from here, and I encourage you to visit that site to consider more of her erudite commentary, and see more of her paintings there.

“Sunaura Taylor is an artist, writer, academic, and an activist for both disability rights and animal rights. Her artwork has been displayed internationally and she is currently an assistant professor at UC Berkeley where she teaches classes in animal studies and environmental justice.

Taylor utilizes her lived experience as a disabled person to present new ways of thinking about disability and animals. Through each strand of her multifaceted work, she examines and challenges what it is to be human, what it is to be animal, and how the exploitation and oppression of both are entwined.” (from here)

While considering Taylor’s work, I was also reading Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our Future by Patty Krawec (interestingly, this book was suggested to me by the same friend who introduced me to Taylor’s artwork): there is a story she relates that I’d like to end with, as a final response to Bison Greeting.

“In the spring, the people laid their tobacco on the ground as an offering, and they prayed and sang. Then they sent out runners in the four directions looking for the deer. These runners ran and ran, covering great distances, and one by one they returned. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing. Finally—maybe because this is how it is in stories—the last runner came back and said she had found one young deer, far to the north. This young one had told her that the deer had felt disrespected and threatened. So they left.

The young deer explained that initially they had waited to see if the humans would remember what we knew. But seeing from our behavior that we had no interest in relationship, and no interest in maintaining the agreements we had made with them, they left. This must have been a difficult decision because of the promise that they had made to the Creator that they would take care of us. The deer needed to think about their own survival, though. If we killed them all, they wouldn’t be here to take care of us anyway.

The people sent their diplomats, their elders, and their ceremonial people to meet with the deer, and for as much time as it took, they listened. They listened to the stories and to the harm they had done. They listened to old relationships and memory. They listened to how things should be. They made offerings and agreements.

Only then did the deer return to them. The people agreed to live in respect for the deer. They agreed to take care of the relationship that takes care of them.”

More of Sunaura Taylor’s artwork and writing can be found here and here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Komar and Melamid | Yalta Conference, 1982

January 26, 2023Komar and Melamid, Yalta Conference, from the “Nostalgic Socialist Realism” series, 1982

I enjoy speculative fiction and recently was reading Harry Turtledove’s Joe Steele. It’s a stand alone story, but you may be familiar with his Southern Victory series (in which the Confederate States survive the American Civil War, and it stretches into the mid twentieth century, offering alternate – yet familiar – takes on everything from WW I to the Holocaust) or World War / Colonization books. That series of books inject an alien invasion into the midst of WW II. This might sound ludicrous, until you read them and one of the aliens observes that – upon their discovery of Buchenwald and Auschwitz – that clearly humans are monstrously incapable of governing ‘ourselves.’ It’s an interesting tonic to the proliferation of science fiction that posits an alien deus ex machina that proffers the narrative that humans are special – such as Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, for example. Perhaps it’s because Clarke was more hopeful, and much has happened since then…

“The novel [Joe Steele] explores what might have happened had Joseph Stalin been raised in the United States, postulating his parents having emigrated a few months before his birth, instead of remaining in the Russian Empire. It depicts Stalin (in this history, taking the name Joe Steele) growing up to be an American politician, rising to the presidency and retaining it by ruthless methods through the Great Depression, World War II, and the early Cold War. The president is depicted as having the soul of a tyrant, with Stalin’s real-world career mirrored by actions taken by Steele.” (from here)

But I mention Turtledove’s Joe Steele as it reminded me of Komar and Melamid’s painting Yalta Conference, from the Nostalgic Socialist Realism series, 1982. This work has also been the cover image for Boris Groys’ seminal book The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond (2011). The ‘inspiration’ for this painting is a famous photograph.

Komar & Melamid are interesting for their cultivated personas as much as their art. This painting can’t help but offer and foment a myriad of interpretations, drawing upon not just the ‘players’ but the moment it re imagines. Yalta was, after all, the point at which the shaky alliance between the USSR and the United States began to seriously fracture. The employment – or appropriation – of ‘socialist realism’ (a style that was the official style of the USSR but that – to quote a Soviet born historian – was like Pravda, in that you can find some grain of truth by what it ignores) only makes this a ‘scene’ even more about failure (like the Yalta Conference was, towards any peace in a Post WW II world) than progress, with a sprinkling of absurdity and skepticism, with the hushing Hitler and American leader a goggle eyed alien….

Boris Groys, in writing about Komar and Melamid, offered the following about their aesthetic: “[The artists] themselves, however, perceive no sacrilege whatever here, because they consider the religion of the avant-garde to be false and idolatrous.”

More from Groys, that could also apply to this painting, and the multiplicities of potential interpretations of it (combined with the irreverence of Komar and Melamid’s larger practice): “[in] the West, the march of progress is “aimless” – one fashion succeeds another, one technical innovation replaces another and so on. The consciousness that desires a goal, meaning, harmony, or that simply refuses to serve the indifferent Moloch of time is inspired to rebel against this progress. Yet the movement of time has resisted all rebellions and attempts to confer meaning upon, control, or transcend it.”

More of Komar & Melamid’s work – and their unique aesthetic and legacy – can be enjoyed here. If you’re interested, more about Boris Groys’ writings and ideas can be read here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Romina Ressia | Woman with a Water Pistol, 2014

January 6, 2023Romina Ressia | Woman with a Water Pistol, 2014

Most of the writing around Ressia’s photographs talks about absurdity and anachronism: perhaps that’s because she appropriates form and redefines meaning in a manner that challenges art historical tropes around gender and relevance. Meticulously executed, her ‘portraits’ have a gravitas on the one hand, but then this is broken by elements that can’t help but amuse (though her people never crack a smile, with eye contact that might wilt any irreverence from the viewer).

There is a hint of dourness to the woman who is the player in this series, and many others, having a heavy handed seriousness that is then fractured by the various objects her subjects are brandishing that seem silly and puerile.

Bluntly, Messia’s Woman with a Water Pistol looks like she’s had just about enough of you, young man, and unless you want to be sprayed with water – disciplined like an unruly, disobedient cat – you’d best behave. You shan’t be told again.

A bit flippant perhaps. But consider the [still, uninterrupted] proliferated misogyny in Western art history [or contemporary art] of women as object, or demure commodity, or the validation / apologia of rape as seen with Europa or the Sabine women or ‘Susannah and the Elders’ (and so, so many others). Consider that in (recently done) 2022 we’ve seen groups of women around the world make it clear that they have had *quite* enough and my interpretation is not without consideration….

This image is part of a larger series titled How would have been Childhood? with the same figure in them all, her unimpressed body language acting as a unifying aspect of the artworks. Birthday hats, costumes, balloons – nothing seems to inspire joy, here. When I first encountered this series online, a birthday party that no one was enjoying – if anyone even came, besides the ‘star’ of the series – can be forgiven for being an initial impression….

“Romina’s art cleverly initiates dialogue on important contemporary social issues through the striking use of anachronistic tropes juxtaposed with mundane and banal elements of modernity. Indeed, the influence of classical artists like Da Vinci, Rembrandt and Velazquez is instantly recognizable in the palettes, textures, ambiance and scenes captured in Romina Ressia’s works, bequeathing them an air of familiarity which only serves to highlight the contradictory and sometimes confrontational presence of objects of modernity such as cotton candy, bubble gum, microwave popcorn and Coca Cola.

The theatrical absurdity in her pictorial compositions, which combine stylistic elements of Renaissance paintings and Pop art, and the dissonance of the stark contradictions captured therein have a surprising clarity, making for an honest critique through visual dialogue of received notions of modernity. In this sense, Romina succeeds in achieving her artistic intent which is not to recreate or refer to the past but to establish a frame within which to interrogate the perceived evolution and progress of society especially in respect to the role and identity of women.” (from here)

If you’re doltish enough to suggest ‘she’d look better if she smiled’, don’t be surprised if you get soaked – deservingly.

More of Romina Ressia’s evocative – if a bit disquieting – work can be seen here.

Her Instagram is @rominaressia

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Haruko Maeda | Self – Portrait with my cat and my grandmother in a glass, 2020

December 2, 2022Haruko Maeda | Self – Portrait with my cat and my grandmother in a glass, 2020

Several years ago, when I was going through the library of a recently deceased friend – at the invitation of his daughter – I noticed in his (former) apartment that she had a velvety bag, looking lustrous and fancy. I asked if this was some expensive alcohol, to mark her father’s passing. She told me it was her father’s ashes. When I asked if they’d be scattered in the city we were in, as he’d lived there for some time, contributing to the critical writing community and being a significant voice around visual culture and especially photography, or back in his home province in the Maritimes, she tersely commented she had not decided yet whether they’d be flushed down the toilet or mixed in with the cat litter.

When my own father passed several years ago, not long before COVID, the arrangements around his inurnment were put on hold: his ashes sat on a shelf in the living room of what is now my mother’s house for some time, only recently being put underground this past summer. Frankly, having ‘him’ in the same room where he spent most of the final years of his life seemed to comfort my mother: he was more agreeable than he’d been in decades, ahem.

No, I am not smiling – my face is as stoic and unreadable as Maeda’s, in her painting.

Those are both dark places to begin in considering Haruko Maeda’s painting Self – Portrait with my cat and my grandmother in a glass: but the funerary rites and rituals of family are nothing if not contested narratives that bring feelings to the surface, re opening old wounds and making new ones. Leave the dead to bury the dead, they (Matthew and Luke, to be specific, but that may just be hyperbole) say, but they never truly ‘leave’ us….

Maeda looks unperturbed in this scene: her cat seems relaxed, and even the fly that perches upon her arm that holds the ashes of her grandmother is subtle.

“Japanese Haruko Maeda lives and works in Austria since 2005. In her art she combines the Shintoistic traditions of her homeland with the Roman Catholic faith, deeply rooted in Austrian culture and history. This allows her to position herself between East and West. Maeda lets these double belongings function as a kind of filter through which she can process her own memories and experiences. The purpose is to raise universal questions about existence, life and death.” (from here)

In Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series, the final story arc – The Wake – offers several vignettes as concluding narratives about death, loss and mourning. One of these involves a man cast into exile, after the death of his son, who gets lost in a desert that his guides will not name, as to do so is to invite disaster. Master Li finds a tiny kitten as a companion, a ward, perhaps, against the ghosts of the dead he encounters in the ashy, shifting sands. At some point he encounters the shade of his son, and this is their conversation:

“Father? I am your son. That is only a kitten. Why do you abandon me to chase after it?”

“When you were alive, you were all my joy. Now you are dead. I see you only in my dreams. And when I awake my pillow is wet with tears. The kitten is living, and it needs my help.”

There is a solemnity to Maeda’s work, but also just a touch of irreverence.

More of Haruko Maeda’s work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments