In: WW II

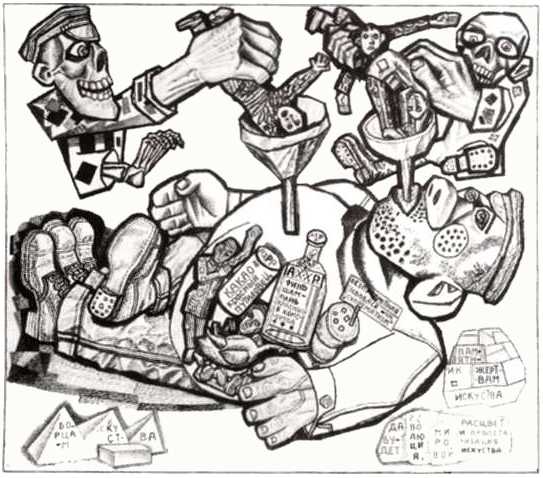

Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

October 21, 2022Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

He was walking about with a noose round his neck and didn’t know. So I told him what I’d heard about his poems.

. . . . . . . .

Yevgraf: This is a new edition of the Lara poems.

Engineer: Yes, I know. We admire your brother very much.

Yevgraf: Yes, everybody seems to.. now.

Engineer: Well, we couldn’t admire him when we weren’t allowed to read him…

Yevgraf: …No.

(both quotes from Boris Pasternak’s tale of Russia before and after the Russian Revolution Dr. Zhivago)

A defining book in my reading and understanding of art history in the 20th century is Boris Groys’ The Total Art of Stalinism: begun when the USSR was still in existence, Groys was able, with the fall of that empire, to access more information, and offer a more nuanced take upon the years post Russian Revolution, as it pertains to the arts in that rare and unique historical moment. Amusingly, I became aware of it after participating in a panel about modernism, and horrifying my fellow speakers by stating that it had failed, horribly, but that its relevance was in its ideals…

Several points stay with me, in considering Pavel Filonov’s work. One is that, in a correlation to the backward economic state of Russia making it fertile ground for a radical new approach and the subsequent revolution, the artistic milieu also suffered from this. It’s not incidental that so many significant artists – not just to Russia but to ‘western’ art history – like Malevich or the Suprematists flourished during the first heady days of the NEP. Experimentation and a sentiment that ‘anything was possible’ was pervasive and defining, with a desire to irrevocably fracture from the ‘old.’

This, of course, all ended badly, and the promised freedoms – whether artistic or personal – were soon not just reigned in, but suppressed, and a cultural exodus from the USSR to other places was predictable.

Filonov (1883 – 1941) served in WWI and would die of starvation during the siege of Leningrad, the once and present St. Petersburg, in the war that followed the ‘war to end all wars.’

The painter, art theorist and poet was an outsider, even during the pre and immediately post revolutionary days of promise: after several failures, in “1908 Filonov was admitted at last to the Academy of Arts. His works attracted the attention of both students and professors by their unusualness: they were not abstract and depicted their subject with full likeness, but were executed in garish, bright colors – reds, blues, greens and oranges. This manner did not conform to the Academy standards, and Filonov was dismissed “for influencing students with the lewdness of his work”. Filonov protested the decision of the rector Beklemishev, and was rehabilitated, but after studying for two years he left the Academy in 1910.”

He was one of many whose works were deemed degenerate, as they eschewed official socialist realist policy. He’d be lost to us, in terms of history, but for the efforts of his sister Yevdokiya Nikolayevna Glebova: “She stored the paintings in the Russian Museum’s archives and eventually donated them as a gift. Exhibitions of Filonov’s work were forbidden. In 1967, an exhibition of Filonov’s works in Novosibirsk was permitted. In 1988, his work was allowed in the Russian Museum. In 1989 and 1990, the first international exhibition of Filonov’s work was held in Paris.

During the period of half-legal status of Filonov’s works it was seemingly easy to steal them; however, there was a legend that Filonov’s ghost protected his art and anybody trying to steal his paintings or to smuggle them abroad would soon die, become paralyzed, or have a similar misfortune.”

It’s unsurprising that Filonov was deeply influence by fellow dissident Klebnikov: and his works – whether the obvious disdain present in this piece The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, or the more stark Those Who Have Nothing To Lose, or Animals, that would make a fine illustration for Orwell’s Animal Farm decades later – have an unflinching quality.

More of Filinov’s life and legacy can be learned here (and was the source cited for the biographical quotes about his life and work).

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

José Clemente Orozco | The Clowns of War Arguing in Hell, 1944

October 6, 2022José Clemente Orozco | The Clowns of War Arguing in Hell, 1944

Fresco, Palacio de Gobierno, Guadalajara (alternately known as Carnival of the Ideologies).

Do I look like the kind of clown that could start a movement? (from the film Joker, 2019)

And butchered, frantic gestures of the dead. (Siegfried Sassoon, 1886 – 1967)

This fresco, created only five years before the artist’s death, is a good example of how ‘Orozco’s late works were characterized by a deep sense of anguish and pessimism as the artist grew skeptical about the future of humanity in the wake of sweeping technological advancements.’ (from here) The facile art historical reading is that this work was Orozco’s reaction to WWII, but even a quick perusal of his impressive body of work, and the cultural and social milieu he existed within, will indicate that this is a more complex and personal artwork than that.

It is, bluntly, a horrifying piece, and intended to be so: painted in the final days of WW II, one might see this as the answer to that image of the conference at Yalta, with FDR, Churchill and Stalin, still pretending to be allies and not with their knives out to gluttonously divide the spoils of war.

Recently I was lucky enough to write about the work of Orozco’s colleague Rufino Tamayo, who eschewed the political discourse that this artist – and other contemporaries like Diego Rivera or David Alfaro Siqueiros – considered essential to Mexican art. Orozco is at the opposite end of this spectrum from Tamayo: in this regard, Octavio Paz [the internationally renowned essayist and poet] once remarked “Orozco never smiled in his life.” (from here) Perhaps that is because – as with this work – Orozco had little use for genteel diplomacy, and knew that once you saw horrors, it was a conscious act of morality to not look away….I am also researching the Russian – Canadian artist Paraskeva Clark, right now, and her aesthetic was to respond to, and reflect, the world she lived within. That is what Orozco is doing here.

But if I’m honest, the reason this older work holds my attention now and I want to share it here is because it seems that very little has changed, in our political discourse, and that we’re still – willingly or press-ganged – onto Das Narrenschiff [A Ship of Fools], a favourite theme of Hieronymous Bosch and so many others….

A quick perusal of the civic candidates standing for office in my space of Niagara only emphasizes this appropriate cynicism.

Much more about Orozco’s life and legacy can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments