In: black and white

Lowell Shaver | Process

April 12, 2024Dave Green | Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024

‘Time is nothing. We have our memory. In memory there is no time. I will hold you in my memory.

And you, maybe you will remember me too.’

(J.M. Coetzee, The Pole)

There is a Salvatore DiFalco quality to Dave Green’s photographs. It’s not just the scenes he presents us, but also the deep almost oily blacks and the grain of the film in many of his photographs. There is a physicality to these scenes, even when seen online : unsurprising, as he’s a photographer who is all about the photographic print and not just within the digital milieu of the present day, that has both its advantages and failings….

DiFalco is a writer and literary critic : I first encountered his fiction in a Canadian literary magazine in the early 2000s and this inspired me to seek out his book of short stories Black Rabbit & Other Stories.

These are urban stories, gritty snapshots of people who are frequently flawed and even, perhaps, a bit repellent. They take place in Toronto or Hamilton or even my own territory of the rust belt wonderland of Niagara, and several memorable ones that are situated in the latter two sites are as engaging as they are grotesque. The characters that inhabit DiFalco’s Black Rabbit (from Stories or Outside or Rocco or Alicia) could also populate some of the scenes that Green presents to us. Green’s work is not quite so dire or dour, nor quite as nihilistic, but his photographs do intersect with DiFalco’s world, whether literally (in his choice of places or his on the cuff captures of his immediate world) or through implication, with the unembellished frankness of Green’s photographs.

Death is also close in DiFalco’s stories : and the image that spurred this response to Green’s work – Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024 – also speaks to an affinity, if not a comfort, with stark endings and perhaps remembrance, perhaps not.

[gallery link="file" size="medium" ids="5984,5985,5986"]

From the artist’s site : Dave Green was born in Toronto (1963), Ontario and grew up in the small Southern Ontario city of Owen Sound. In the early 1980s he moved back to Toronto to study photography at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute (now Toronto Metropolitan University). He has worked as a house painter, a fibreglass worker, a photography technician and as an educator. He served as an instructor of photography at Ryerson’s Chang School of Continuing Education and has taught photography to youth affected by violence. He has travelled extensively throughout Canada, the United States and Europe, always with a camera.

The words of LP Farrell, from the introduction to Green’s book Personal (Dumagrad Books, 2017):

Looking at some of these photographs now, the prescience startles and the storefront facade windows, the tired barren highways, the sombre diners seem less a lament or nostalgic yearning for a different time, which is what I thought back then, than a crystal ball, sometimes literally reflecting, but often revealing a life marked by deep solitude. It is as though Dave saw, understood and then showed us what would happen to us all before life hit. Dave Green has photographed a world already disappearing like a picture not quite fixed, time remorseless and unrelenting. Time doing its thing.

———————————————————

This is a book of contrasts, the tension in the dialogue a whisper. Look here: youthful lust and yearning, women and lovers juxtaposed with landscapes busted and stripped down. Lust is a counterpoint to dilapidation. The tang of tungsten light in cavernous bars and then a street lamp, suddenly a votive light in a night sky over lovers like some crazy benediction. As if there was hope…

You can see more of Green’s work at his site here and his IG is here. Green is also represented by the MF Gallery.

If there is a reckoning, it is on the road. The photographer/passenger, the night and a beautiful woman at the wheel; a motorcyclist with a life garbage-bagged and strapped to the saddle of his BSA, maybe in flight. A bleak stretch of road ahead, road the arbiter. Love goes but the road always stays. Road, the redeemer.

LP Farrell, from the introduction to Green’s book Personal (2017)

They drove in silence, the landscape a work in charcoals and flaked quartz.

———–

What the fuck did he just do? He stopped running. He was out of breath.

He looked around him. He was standing nowhere.

(Salvatore DiFalco, from the short story Pink, from Black Rabbit & Other Stories)

I’ll end with how I feel an affinity for Green’s images of the rust belt wonderland : I could be looking at the streets I haunt in St. Catharines or Welland, and even the older images from the 1980s offer a run down weariness, a punky nostalgia, that I also remember from my youth in Niagara. I see echoes of Chris Killip or Tish Murtha, in the images of Dave Green as much as I see my own city, too.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

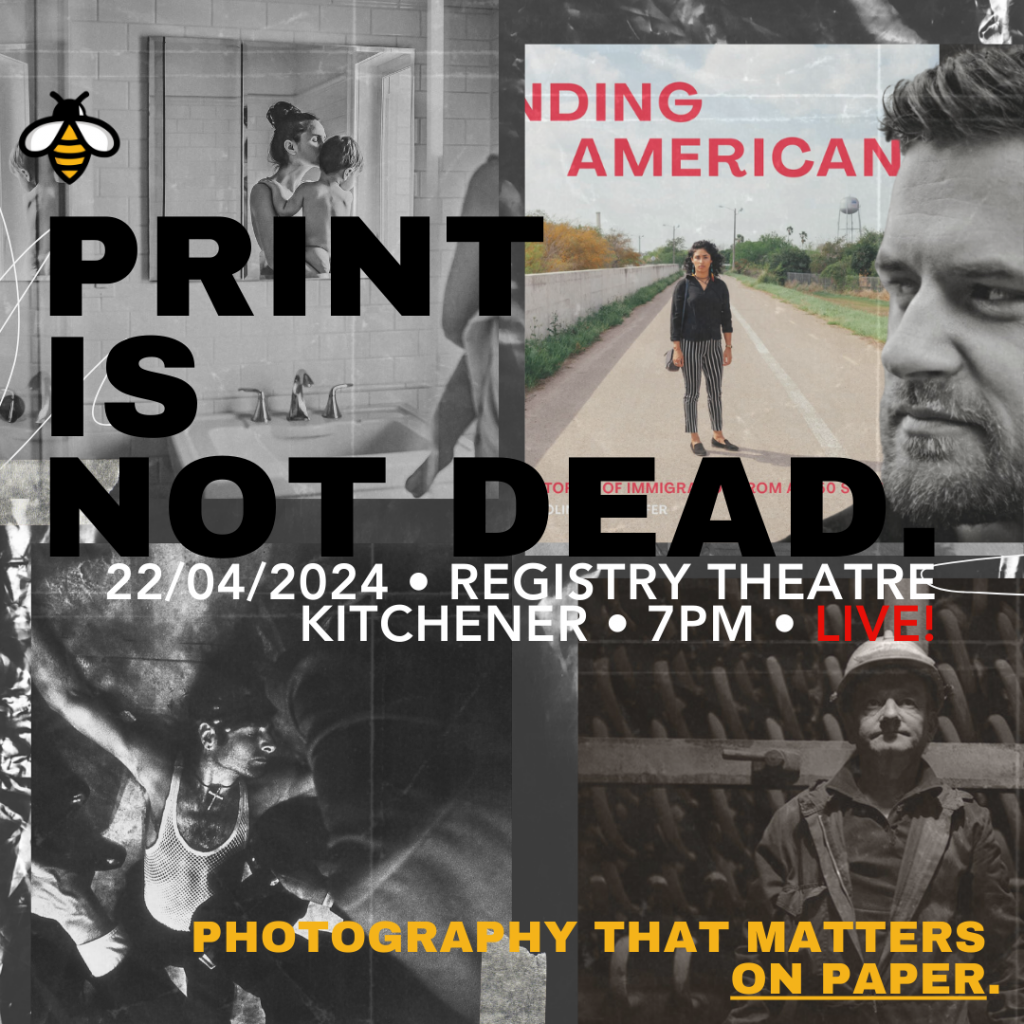

Print is Not Dead | Photography That Matters ON PAPER

April 12, 2024PRINT IS NOT DEAD| PHOTOGRAPHY THAT MATTERS ON PAPER

APRIL 22, 7PM

Registry Theatre, Kitchener, ON

Tickets HERE $15 (also available at the door)

Camera sale starts at 5:30PM @londonvintagecamerashow

In a world of fast image-heavy, screen-based storytelling, why do artist still see value in slow printed photographs? Is it still possible to become a published artist/photographer in Canada? Why are these photographers still concerned with the analog world?

Join local photographers, Colin Boyd Shafer @colinboydshafer , Robin Claire Fox @robinclairefox , and Karl Griffiths-Fulton for a panel discussion hosted by photoED Magazine’s publisher Rita Godlevskis @photoedmagazine to share the pros and cons of (now) rare analog experiences.

This live, in-person discussion will NOT be recorded and will exclusively share the behind the scenes stories of IRL humans that have successfully presented their work in high-quality PRINT.

Join us to learn more about how these local folks created their legacy works, and stick around for some qualitative peer-to-peer networking, connecting, and supporting these incredible (and rare) Canadian projects.

Stick around to review these artists works on paper. Photo books and magazines will be available for sale. Support incredible local photography IN PRINT.

SPECIAL BONUS! Ron and Maureen Tucker of the LONDON VINTAGE CAMERA SHOWS will be onsite, allowing us all to ogle and purchase their quality analog cameras and accessories Sale starts at 5:30 until 6:50 and then after the panel discussion.

Presented by curated. @thecovertcollective

Want more information? DM @thecovertcollective

Read More

Dave Green | Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024

April 12, 2024Dave Green | Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024

‘Time is nothing. We have our memory. In memory there is no time. I will hold you in my memory.

And you, maybe you will remember me too.’

(J.M. Coetzee, The Pole)

There is a Salvatore DiFalco quality to Dave Green’s photographs. It’s not just the scenes he presents us, but also the deep almost oily blacks and the grain of the film in many of his photographs. There is a physicality to these scenes, even when seen online : unsurprising, as he’s a photographer who is all about the photographic print and not just within the digital milieu of the present day, that has both its advantages and failings….

DiFalco is a writer and literary critic : I first encountered his fiction in a Canadian literary magazine in the early 2000s and this inspired me to seek out his book of short stories Black Rabbit & Other Stories.

These are urban stories, gritty snapshots of people who are frequently flawed and even, perhaps, a bit repellent. They take place in Toronto or Hamilton or even my own territory of the rust belt wonderland of Niagara, and several memorable ones that are situated in the latter two sites are as engaging as they are grotesque. The characters that inhabit DiFalco’s Black Rabbit (from Stories or Outside or Rocco or Alicia) could also populate some of the scenes that Green presents to us. Green’s work is not quite so dire or dour, nor quite as nihilistic, but his photographs do intersect with DiFalco’s world, whether literally (in his choice of places or his on the cuff captures of his immediate world) or through implication, with the unembellished frankness of Green’s photographs.

Death is also close in DiFalco’s stories : and the image that spurred this response to Green’s work – Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024 – also speaks to an affinity, if not a comfort, with stark endings and perhaps remembrance, perhaps not.

From the artist’s site : Dave Green was born in Toronto (1963), Ontario and grew up in the small Southern Ontario city of Owen Sound. In the early 1980s he moved back to Toronto to study photography at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute (now Toronto Metropolitan University). He has worked as a house painter, a fibreglass worker, a photography technician and as an educator. He served as an instructor of photography at Ryerson’s Chang School of Continuing Education and has taught photography to youth affected by violence. He has travelled extensively throughout Canada, the United States and Europe, always with a camera.

The words of LP Farrell, from the introduction to Green’s book Personal (Dumagrad Books, 2017):

Looking at some of these photographs now, the prescience startles and the storefront facade windows, the tired barren highways, the sombre diners seem less a lament or nostalgic yearning for a different time, which is what I thought back then, than a crystal ball, sometimes literally reflecting, but often revealing a life marked by deep solitude. It is as though Dave saw, understood and then showed us what would happen to us all before life hit. Dave Green has photographed a world already disappearing like a picture not quite fixed, time remorseless and unrelenting. Time doing its thing.

———————————————————

This is a book of contrasts, the tension in the dialogue a whisper. Look here: youthful lust and yearning, women and lovers juxtaposed with landscapes busted and stripped down. Lust is a counterpoint to dilapidation. The tang of tungsten light in cavernous bars and then a street lamp, suddenly a votive light in a night sky over lovers like some crazy benediction. As if there was hope…

You can see more of Green’s work at his site here and his IG is here. Green is also represented by the MF Gallery.

If there is a reckoning, it is on the road. The photographer/passenger, the night and a beautiful woman at the wheel; a motorcyclist with a life garbage-bagged and strapped to the saddle of his BSA, maybe in flight. A bleak stretch of road ahead, road the arbiter. Love goes but the road always stays. Road, the redeemer.

LP Farrell, from the introduction to Green’s book Personal (2017)

They drove in silence, the landscape a work in charcoals and flaked quartz.

———–

What the fuck did he just do? He stopped running. He was out of breath.

He looked around him. He was standing nowhere.

(Salvatore DiFalco, from the short story Pink, from Black Rabbit & Other Stories)

I’ll end with how I feel an affinity for Green’s images of the rust belt wonderland : I could be looking at the streets I haunt in St. Catharines or Welland, and even the older images from the 1980s offer a run down weariness, a punky nostalgia, that I also remember from my youth in Niagara. I see echoes of Chris Killip or Tish Murtha, in the images of Dave Green as much as I see my own city, too.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Clarence John Laughlin | Southern Gothic

March 12, 2024Clarence John Laughlin (1905 – 1985) | Southern Gothic

Laughlin was a New Orleans photographer : he’s best known for his black and white, sometimes uncanny and disquieting images of the Southern United States. Considering the ethereal and dream like quality of many of his scenes, he’s sometimes spoken of as the father of American Surrealism. In considering his photographs, the ‘original’ definition of Surrealism from André Breton was to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality.” Less pretentiously (Frida Kahlo did refer to Breton as being among the ‘art bitches’ of Paris, whom she disdained, ahem), in the work of Laughlin, one can see that he was attempting to both re interpret and define his own memories and experiences of a site, while also employing the place and people within it, that is rife with contested narratives.

I tried to create a mythology from our contemporary world. This mythology — instead of having gods and goddesses — has the personifications of our fears and frustrations, our desires and dilemmas.

(Clarence John Laughlin)

For those unfamiliar : ‘Southern Gothic is an artistic subgenre…heavily influenced by Gothic elements and the American South. Common themes of Southern Gothic include storytelling of deeply flawed, disturbing, or eccentric characters who may be involved in hoodoo [or the large sphere of the occult], decayed or derelict settings, grotesque situations, and other sinister events relating to or stemming from poverty, alienation, crime, or violence.’ (from here)

As darkness set in, the mist drifted off the deep acreage of sugarcane that flattened back to the surrounding slough and mire. Blooming loblolly bushes, palmettos, and thick fields sprouting a type of flower he’d never seen before filled the evening air with an assertive but sweet fragrance.

The Nail family lived in an antediluvian mansion that had been built long before the separation of states. He saw where it had been rebuilt after Civil War strife and he could feel the dense and bloody history in the depths of the house. He glanced up at a row of large windows on the second floor and saw six lovely pale women staring down at him.

————————

A tremendously wide stairway opened to a landing where colonnades rose on either side abutting the ceiling. He could see the six sisters huddled together at the banister curving down from the second floor, all of them watching him, their hair sprawled over the railing. He waved, but only one of them responded, lifting her hand and daintily flexing her fingers.

(Tom Piccirilli, Emerald Hell)

The book I quote above takes place primarily in Louisiana – where the artist who’s the focus of this essay was born, and a place, whether in terms of New Orleans (his birthplace) or the greater Southern Reach (a term I borrow from another author), that defined his aesthetic. In that book, there are many dark characters that are pervasive within Southern Gothic horror that’s a wide genre, one which I’ve been quite interested in of late. The aforementioned Nail family’s daughters suffer under a ‘curse’ where they cannot speak, and seem to move about the massive manse like apparitions, veiled and almost insubstantial, like a breeze accentuated by their long dresses and hair (like so many lamenting female ghosts of the South, and elsewhere).

Another player in Emerald Hell is known only as ‘the walking darkness’ or ‘Brother Jester’ : a former evangelical preacher who, after surviving an attempt made on his life, wanders the highways and byways of the state, leaving human wreckage in his wake. A later day incarnation of Robert Mitchum’s ‘man of god’ in the film Night of the Hunter (1955), perhaps. I am also reminded of some of the desolate – but drenched in histories and stories, almost like a stain on the ground – landscapes from the first season of True Detective, which is another iteration of the essence of the Southern Gothic.

One could imagine Laughlin’s images as characters and tableaux for such a chronicle. In this sense, Laughlin is a storyteller, an historian, just like Michael Lesy, who took us on a Wisconsin Death Trip…

Ghosts exist for a purpose. Unfinished business, delayed revenge, or to carry a message. Sometimes the dead can go to a lot of trouble to bring a desperate warning of some terrible thing that’s coming.

Whatever the reason, don’t blame the messenger for the message.

(Simon R. Green, Voices from Beyond)

I attempt, through much of my work, to animate all things—even so-called ‘inanimate’ objects–with the spirit of man….the creative photographer sets free the human contents of objects; and imparts humanity to the inhuman world around him.

(Clarence John Laughlin)

Born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, Laughlin had a difficult childhood, and this – in tandem with his ‘southern heritage’ and literary interests – are touchstones for his work. The family moved to New Orleans in 1910 after further economic hardship, with his father working in a factory in the city. A quiet, introverted child, Laughlin had a close relationship with his father whose encouragement – especially in terms of Laughlin’s interest in literature – was important to his development as an artist. His father’s death in 1918 affected him greatly : the dark, funerary, epitaphic nature of much of his work, perhaps, echoes this loss.

Laughlin never completed high school, but was a “highly literate man. His large vocabulary and love of language are evident in the elaborate captions he later wrote to accompany his photographs.

Laughlin discovered photography when he was 25 and taught himself how to use a simple 2½ by 2¼ view camera. He began working as a freelance architectural photographer and was subsequently employed by agencies as varied as Vogue Magazine and the US government. Disliking the constraints of government work, Laughlin eventually left Vogue after a conflict with then-editor Edward Steichen. Thereafter, he worked almost exclusively on personal projects utilizing a wide range of photographic styles and techniques, from simple geometric abstractions of architectural features to elaborately staged allegories utilizing models, costumes, and props.” (from here)

From the High Museum of Art in Georgia (the accompanying text for a retrospective of Laughlin’s work) : “Known primarily for his atmospheric depictions of decaying antebellum architecture that proliferated his hometown of New Orleans, Laughlin approached photography with a romantic, experimental eye that diverged heavily from his peers who championed realism and social documentary.”

More about his work and life can be enjoyed here and here : and perhaps, while perusing these images, consider listening to another Southerner – Johnny Cash – and his song The Wanderer, that also offers (ironically, considering the title) a place to stand, intertwined with histories both personal and more public, when considering the photographs of Clarence John Laughlin.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Adrianna Ault & Raymond Meeks | Ohio Farm Auction

December 11, 2023Adrianna Ault & Raymond Meeks | Ohio Farm Auction

The crops we grew last summer weren’t enough to pay the loans

Couldn’t buy the seed to plant this spring and the Farmers’ Bank foreclosed

Called my old friend Schepman up, to auction off the land

He said, “John it’s just my job and I hope you understand”

Hey, calling it your job ol’ hoss, sure don’t make it right

But if you want me to I’ll say a prayer for your soul tonight

(John Mellencamp, Rain on the Scarecrow)

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever. (Ecclesiastes 1:4, KJV)

There’s a memento mori quality to the scenes from the Ohio Farm Auction series. This may be an interpretation informed by several of the other bodies of work by Adrianna Ault (such as her series Levee which led me to the collaborative Ohio Farm Auction series), that are permeated by a sense of mortality and remembrance, as expressed in her writings about those images.

Though these images are not completely empty of people, the more striking and – unsurprisingly – starker moments that stay with you have no figures within them, though their absence and implication is powerful. The line I quote above, in response to this work came to mind immediately upon seeing the Township photos. Mellencamp’s album was a series of laments for a way of life lost (perhaps taken away or relinquished), as the world moves on (this last being closest, I feel, to the artists’ position here, with a gentle consideration of family history and generational change. Township reads more about releasing than resistance..)

The biblical quote came to me in a more indirect manner. Having recently read George Stewart’s post apocalyptic book Earth Abides (from 1949, so it ages poorly, in many ways – or this is perhaps a corolary to the ‘change’ implicit in the story presented in Ohio Farm Auction, of a time to gather and a time to discard), the ideas, again, of what is lost and our – humanity’s – place in the larger narrative of the earth was a further consideration when I engaged with these photographs…

The words of Adrianna Ault, speaking of this collaboration with Meeks (one of a number they’ve done) :

“These photographs were taken one February day in a rural township in Ohio. My partner, Raymond Meeks, and I photographed and watched as all the possessions of my family’s farm was auctioned to the highest bidder. Photographing served as a testimony to the life and work of over one hundred years of farming in my family. This work was published as a collaboration with Tim Carpenter and Brad Zellar in the book Township published by TIS books and later nominated for the 2018 Kassel Fotobookfestival Award.”

That collection of words and photographs has been described as a “careful deliberation on transience and the ultimate meaning of a way of life in the Midwest.”

More of Ault’s work can be seen here and more of Meek’s work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

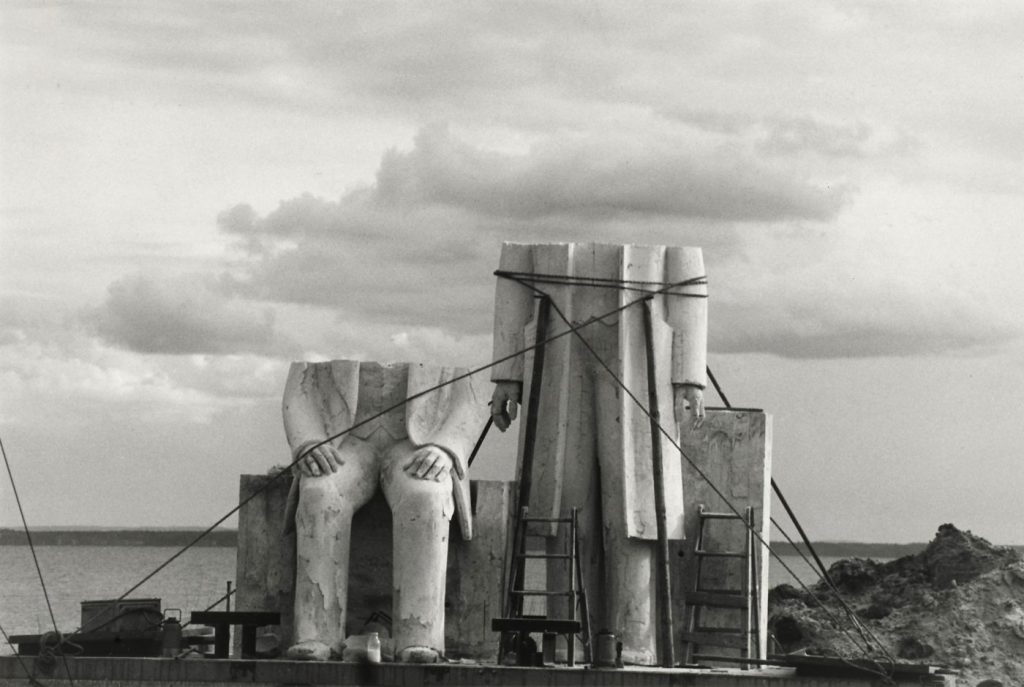

Sibylle Bergemann | The Monument | 1975 – 1986

November 6, 2023Sibylle Bergemann | The Monument | 1975 – 1986

Nothing seems more improbable than what people believed when this belief has gone with the wind. (Doris Lessing)

I am old enough to remember when the Berlin Wall fell and the end of the Cold War. In a fine inversion – and something that speaks to how history is often a collaborative delusion and how, at its best, art history can be the most direct and yet most subversive form of history – I would be teaching a decade or so later and have to explain to students what both of those events were, and why they still mattered. That was also a time when I reread Doris Lessing (I recommend her award winning – and divisive, to many readers and critics – book The Good Terrorist) : I had disdain for her books when I read them in my early twenties, and was surprised at how much more sense they made to me, as I had matured and gained experiences that resonated with her words, when I was older. At that time, I was able to appreciate her words – and especially the sentiment behind them – that I quote at the start of this essay a little better….

Critic Jane Rogers (in The Guardian) described The Good Terrorist as “witty and … angry at human stupidity and destructiveness.” I must inject (as one can’t look at these images by Sibylle Bergemann and not consider the contested legacy of Marx and Engels, communism and the GDR) how I like to antagonize my christian and communist friends (not the same people, to be clear) by citing Mordecai Richler from his seminal book Solomon Gursky Was Here. In the voice of the aforementioned Gurksy, Richler avers that the system (whether the Sermon on the Mount or the Communist Manifesto) is inspired but it is humanity that is vile…

Enough tangential commentary, let’s have some facts : “From 1975 until 1986 Sibylle Bergemann accompanied the making of the huge bronze of Marx and Engels in Gummlin / Usedom from the first sketches to the installation. The work, which was created by the sculptor Ludwig Engelhardt, is still located near the Alexanderplatz in Berlin-Mitte.” There has been controversy about this monument, as Germany struggles with its past as defined in the present, whether it be the theoretical space of Marxism or that the GDR was one of the most repressive states in the 20th century. Monuments, after all, occupy both physical space and conceptual ground in any national imaginary.

In tandem with this, I’d suggest watching the ‘tragicomedy’ film Goodbye, Lenin : “the story follows a family in East Germany (GDR); the mother is dedicated to the socialist cause and falls into a coma in October 1989, shortly before the November revolution. When she awakens eight months later in June 1990, her son attempts to protect her from a fatal shock by concealing the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of communism in East Germany.” A majority of that film was shot where this sculpture is located, at the Marx – Engels Forum.

First as tragedy, then as farce, ahem, someone (okay, Engels, ahem) said….

Bergemann’s words about her art and aesthetic : “I am interested in the edges of the world, not the center. The incompatible is crucial material for me. When something isn’t right about faces or landscapes that doesn’t quite fit…”

As of this writing, I am also working on an Artist You Need To Know post about the Mexican photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo (1903 – 1993). Bravo’s words also apply to Bergemann’s Monument series : “If anything is useful about my photography, it will be the sense of being a chronicle of my country.”

But I don’t approach this without bias : my stance can be seen in the primary image I’ve chosen, where the figures are ‘missing’ their heads, like a reversal of Shelley’s Ozymandius, where only the legs remain of his forgotten ‘king’….

More about this project can be seen here and more of Bergemann’s photographs can be enjoyed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Chris Alic | Transience & Memory

September 16, 2023Chris Alic | Transience & Memory

One need not be a Chamber – to be Haunted –

One need not be a House –

The Brain has Corridors – surpassing

Material Place –

(Emily Dickinson)

The history of one who came too late

To the rooms of broken babies and their toys

Is all they talk about around here

And rebuke, did you think you’d be left out?

(Peter Straub, from Houses without Doors)

Like Mark Walton – and it’s a defining tenet of curated, I think – I also have a strong presence in my immediate and local visual arts community, with mine being Niagara : several of the artists I’ve featured here (Juliana D’Intino, for example, or Sandy Fairbairn) are ones that I’ve been lucky enough to include in a continuing curatorial project in downtown St. Catharines that began in Fall of 2022 and that is continuing indefinitely, with artists slated into late 2024.

Chris Alic is one of those artists, as her exhibition with Amber Lee Williams is currently on view at Mahtay Café & Lounge. That grew out of a 5 x 2 Visual Conversations evening (a relaxed sharing of art and ideas that I’ve facilitated for over five years, in St. Catharines and Welland). Like any good curator, I offered support to the two artists but primarily stayed out of the way, with some appropriate gentle nagging.

From that immediacy, let’s indulge some of my subjectivity that sparked my interest to consider these two pieces by Alic.

As the artist said when she spoke about the work, these are images from time she spent in Missouri in the United States – and, of late, I’ve fallen down another rabbit hole that centres upon the idea of the aesthetic of the Southern Gothic, whether that be in terms of crime or horror, but usually (and I own this) on the darker side. In light of this, the abandoned and lonely toys of Alic’s images take on a more ominous tone. Further clarification : I’ve been eschewing the ‘standard’ Southern Gothic horror of New Orleans, in my reading and research, but instead have been looking at other sites in the American South – like Charleston, or Alic’s Missouri – as these oft ignored sites have an unexplored richness in their stories that is more diverse than you might think. I also mention this – not just as another subjective indulgence – but because many of the stories I’m encountering in this enjoyable research are defined – or deformed – by the history of those sites (the institutional racism flows into the occult or supernatural horrors of the stories. There’s a story by Alan Moore about a television show that is shot on an old abandoned plantation where the filming somehow invokes the ghosts of the enslaved, and the actors ‘become’ their characters, with new manifestations of hate and racism being merged with old…all horror, they say, comes out of reality….or perhaps even the superficially banal, like Alic’s empty playground and abandoned tricycle….)

The words of the artist :

Memory is a huge part of what makes us human. Every interaction, every step, sight, sound, touch, smell – all these things create memory. But they are fragile. They are guided by perception, they are malleable, layered, are influenced by who we become, and who we become is in part made up of what we remember. Our memories continue to create us, and we create our memories. And we lose them. They fade, disintegrate, become suspect. They are subject to context, transformation and decay, and temporality, just like the spaces we inhabit and the things we use. They become the liminal space between an event and a feeling. Does emotion exist without memory?

I have been using a camera to secure my memories since I was a single-digit kid. I don’t remember ever not having a camera, or access to a camera. It was a part of my childhood, and everyone around me took photos and 8mm film of everyday life. My immediate and extended family were avid documentarians. I am continuing that tradition, but somewhere along the way I made the decision to “crop” those memories – to capture only small portions of context, little bits of an event, inexplicable to anyone but myself because each image is connected to an important moment, an emotion, a piece of who I became because of it. And then I edit. Adjust. Refine. Sometimes intentionally erase, fade, and transform them.

These seven images were made during a two-year period living in Columbia, Missouri. All were taken on a Yashica FX-70 Super 2000 film camera. I learned to use a darkroom and print my own photos with this film, and two of the images were only recently developed using caffenol-c. I had forgotten that I had taken the photos, I had forgotten the existence of the places until I saw them again.

The two person exhibition CHRIS ALIC & AMBER LEE WILLIAMS | TRANSIENCE OF MEMORY is on display at Mahtay Café & Lounge in downtown St. Catharines for the month of September, 2023.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

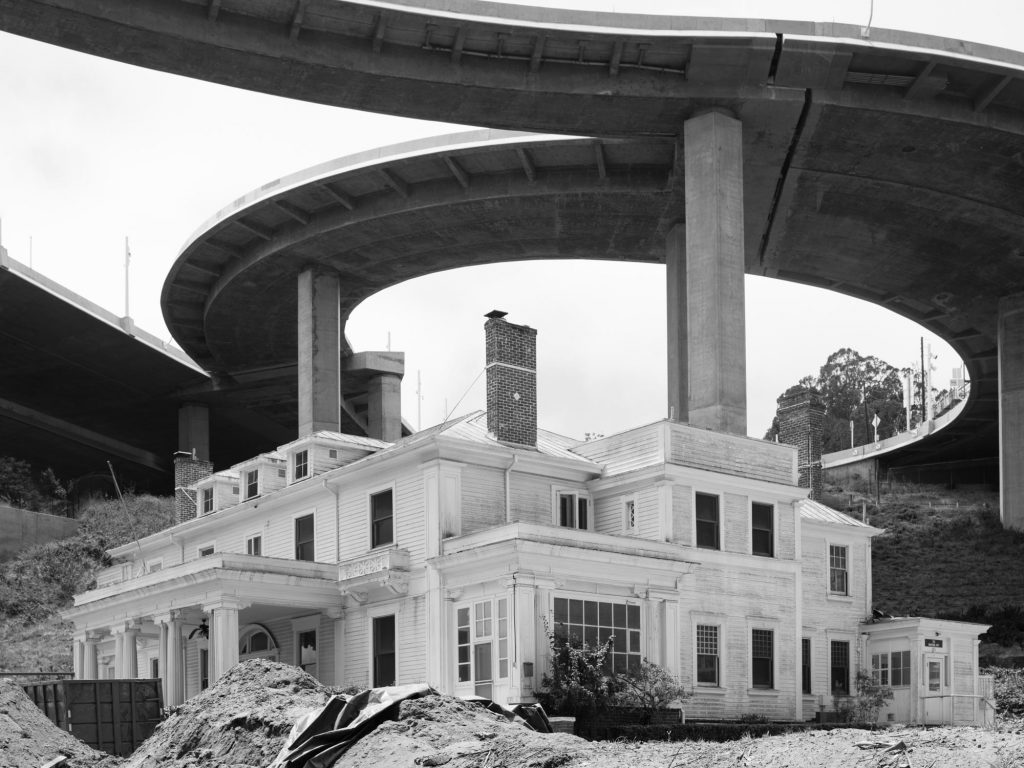

Mimi Plumb | The Golden City, 1984 – 2020

February 2, 2023Mimi Plumb | The Golden City, 1984 – 2020

So this is where the Renaissance has led to | And we will be the only ones to know

So take a drive and breathe the air of ashes | That is, if you need a place to go

If you have to beg or steal or borrow | Welcome to Los Angeles, City of Tomorrow

(Phil Ochs, The World Began In Eden And Ended In Los Angeles)

When I first encountered Plumb’s images, that song from the late Phil Ochs came to mind: it seems upbeat and pleasant but is, in fact, nuanced with a despair that is subtle but builds (and I will admit my interpretation may be coloured by his suicide. But the rendition of that song I am familiar with is a live version, and Ochs talks at the beginning of his fascination with Los Angeles “which intrigues me like a sensual morgue.” Plumb’s works have a certain sterility, to them, as well, that intersects with this consideration).

As with Plumb’s scenes, there’s more at play than the obvious. Considering that California exists in imaginations just as vividly – if not always accurately – as any seminal ‘place’ like ‘Siberia’, Plumb’s photographs invite us to construct narratives around them, that build, converge or perhaps complete what she intends, with her own personal stories….

I will admit that when looking at Mimi Plumb’s photography, that The Golden City often blended with another body of work of hers, titled The White Sky. I doubt that the artist would be offended by that, as the elements of memory, nostalgia and social realism suffuse her practice, and are themes that are present in her artwork still. Although her narrative is a personal one, it also has elements that are more universal, when considering larger tropes that her work touches upon.

“The Golden City [is] a series of images that frames subjects against the sprawling backdrop of San Francisco. Similar to Plumb’s other bodies of work, The Golden City is an ode to an earlier America—a rich and playful elaboration on the human condition, and its tendencies towards hedonism and spectacle. To say that this work largely references the exploitation of the natural world on account of humans would be reductive. While sculptural detritus and empty construction sites set the groundwork for this series, Plumb flips dramatic irony on its head by capturing subjects enthralled by events transpiring just beyond the frame. We are not in on the comings and goings within this world, but are sucked in nonetheless; left only with a sense of wonder at what could be bringing about such awe.” (from Document, with an engaging conversation with Plumb you can read as well)

Much more of Plumb’s work – from this series and a number of others – can be seen here. If you’d like to listen to her talk about her work, the Museum of Contemporary Photography has a video you can enjoy here.

Plumb published a book of selected images from this body of work with Stanley/Barker books in 2022.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

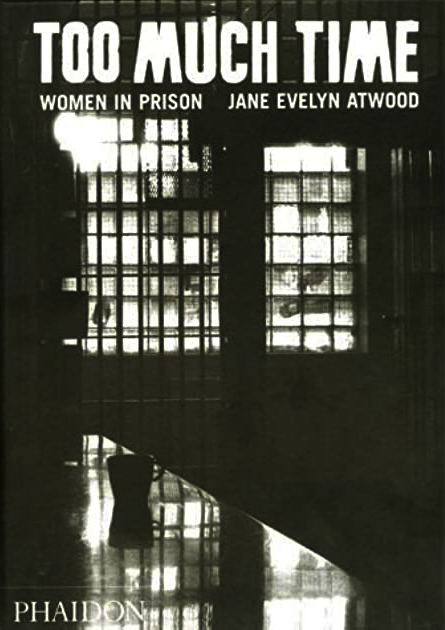

Jane Evelyn Atwood | TOO MUCH TIME: WOMEN IN PRISON, 2000

November 25, 2022Jane Evelyn Atwood, TROP DE PEINES: FEMMES EN PRISON, 2000, Éditions Albin Michel, Paris, France. (OUT OF PRINT)

Jane Evelyn Atwood, TOO MUCH TIME: WOMEN IN PRISON, 2000, Phaidon Press Ltd., London, England. (OUT OF PRINT)

“Curiosity was the initial spur. Surprise, shock and bewilderment soon took over. Rage propelled me along to the end.”

Too many times – and I’m sure I’m not alone in this – I have heard some well meaning dilettante assert that ‘art should be about beauty’ or ‘should only uplift us.’ In terms of that space where photography intersects with ideas of art and documentary – and not to mention history – something that comforts you is most likely wrong, if not simply pablum. When I’m sharing images on social media, there are some photographers I hesitate to post works from (as photography still carries the weight of being more ‘real’, thus can ‘offend’ as well as see yourself banned from those platforms): Gilles Peress is one of those, for his unflinching lens in places from Rwanda to the former Yugoslavia (“I don’t trust words. I trust pictures”), Gordon W. Gahan (specifically his images of the Vietnam War), Donna Ferrato (I was lucky enough to experience her groundbreaking series Living with the Enemy decades ago, in Windsor) or Martha Rosler (her House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home works that had their genesis in response to the Vietnam War (c.1967–72) but that she ‘revisited’ in 2004 and 2008, ‘updating’ them to Iraq and Afghanistan).

But the text I’ve selected for a Library Pick is something that is not ‘there’ but ‘here’, and in that respect is often – easily, repeatedly – ignored.

Jane Evelyn Atwood’s “monumental work on female incarceration, published in both French and English, took Atwood to forty prisons in nine different countries in Europe, Eastern Europe, and the United States. The access she managed to obtain inside some of the world’s worst penitentiaries and jails, including death row, make this ten-year undertaking the definitive photographic work on women in prison to date. Extensive texts include interviews with inmates and prison staff as well as Atwood’s own reminiscences and observations. The prize-winning photos in this book, including the story of an incarcerated woman giving birth while handcuffed, established Jane Evelyn Atwood as one of today’s leading documentary photographers.” (from her site)

Atwood has always used her camera as a means to tell stories too often not even dismissed but denied, and she has granted a level of dignity and consideration to those whom are too often not considered human but detritus.

A good friend is a theologian, but of the liberation theology vein: I enjoy talking with them, as their righteous anger is only matched by their ability to quote that repeatedly translated and edited text with a sense of the public good. I mention them as they once pointed out that in the New Testament, only one person was promised a place in the ‘kingdom of heaven’, and that was one of the criminals being crucified at the same time as Jesus.

In a more modern sense, I might cite Lutheran Minister (and ‘public theologian’) Nadia Bolz-Weber‘s contemporary addendum to the beatitudes, which include ‘Blessed are those who have nothing to offer. Blessed are they for whom nothing seems to be working.’

Atwood published ten books of her work and been awarded the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography, the Grand Prix Paris Match for Photojournalism, the Oskar Barnack Award, the Alfred Eisenstadt Award and the Hasselblad Foundation Grant twice.

More of Atwood’s work can be seen here.

Like several of the books I’ve recommended, this is one I came across in my local library.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

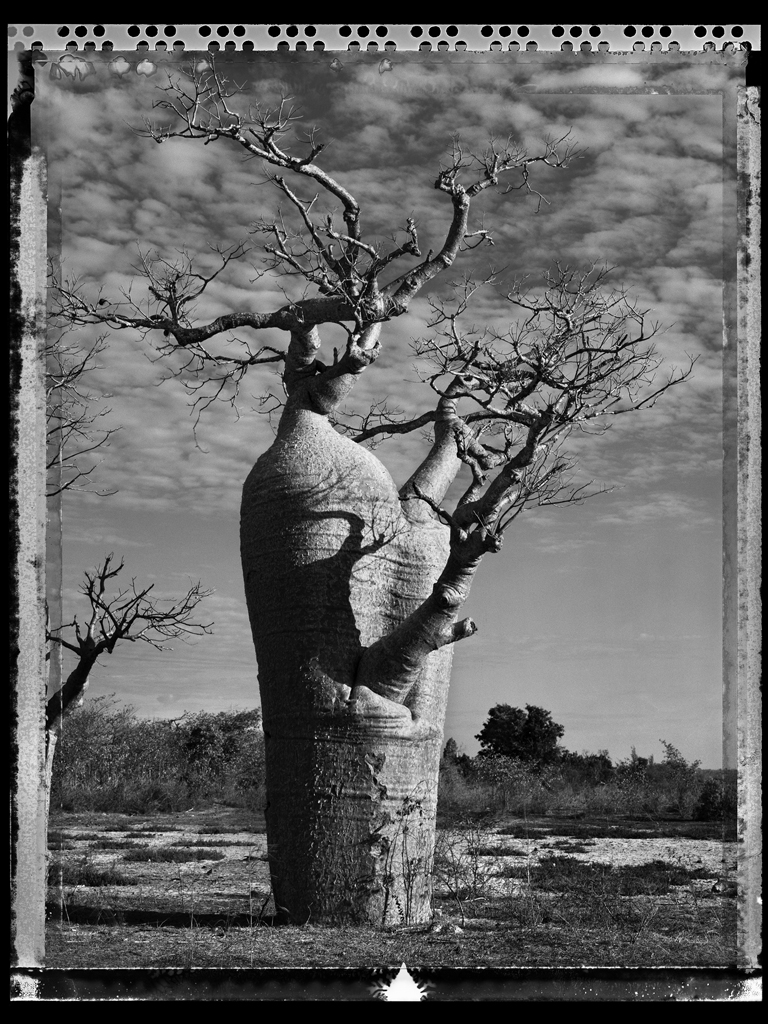

Elaine Ling | Baobab #31 – 2010, Madagascar

November 19, 2022Elaine Ling | Baobab #31 – 2010, Madagascar

Ce qui embellit le désert, dit le petit prince, c’est qu’il cache un puits quelque part…[What makes the desert beautiful, said the little prince, is that somewhere it hides a well…]

It is an odd feeling to encounter the work of an artist, seeing how prolific they are and be enamoured of their practice, then discover that they passed a few years ago. I’ve often had the same experience with authors (I have a habit of finding the work of a writer that is new to me, and consuming all the books, and it’s an empty sadness when you realize they won’t be creating any more).

This image is one from a series titled Baobob, by the late Elaine Ling (1946-2016). At her site it is the final series presented, from an extensive and enthralling body of work.

It can be read as having the quality of an epitaph: these massive, seemingly eternal natural ‘monuments’ that have survived her, and will likely survive all of us.

In that manner I have of being ‘too subjective’, Baobob trees remind me of Antoine de Saint Exupéry’s novel Le Petit Prince (1943): to me, it’s a melancholy story, about loss and death, with touching moments of truth that have contributed to how it – despite often being considered a story for children – speaks to many adults, like myself.

“Seeking the solitude of deserts and abandoned architectures of ancient cultures, Elaine Ling…explored the shifting equilibrium between nature and the man-made across four continents. Photographing in the deserts of Mongolia, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Timbuktu, Namibia, North Africa, India, South America, Australia, American Southwest; the citadels of Ethiopia, San Agustin, Persepolis, Petra, Cappadocia, Machu Picchu, Angkor Wat, Great Zimbabwe, Abu Simbel; and the Buddhist centres of Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Tibet, and Bhutan; she has captured that dialogue.” (from her site)

Voici mon secret. Il est très simple: on ne voit bien qu’avec le cœur. L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux [Here is my secret. It is very simple: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye].

On the first of August, 2016, Elain Ling lost her battle with lung cancer: her brother – Edward Pong – has indicated that he intends to continue to foster her legacy, through the maintenance of Ling’s site.

It is an impressive space with much more about Ling’s life and work – and many more of her moments from her life and around the world – that can be enjoyed here. C’est véritablement utile puisque c’est joli [It is truly useful since it is beautiful].

All quotes in italics are from Saint Exupéry’s The Little Prince .

Elaine Ling was also a recently featured Artist You Need To Know, in AIH Studios’ continuing series. You can enjoy that here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments