In: documentary photography

Emmanuel Georges | America Rewind

July 16, 2024Emmanuel Georges | America Rewind

I am making final edits on this article on the evening of the day of the incident where Trump was shot at, at a Reichsparteitag in Butler, Pennsylvania. I’ll offer no further commentary on this, as at the time of this writing, rumours and partisan commentary is moving at a speed faster than light, and all I can think of is the Reichstag ‘fire’…..that is the disclaimer I offer, before we proceed.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

It is nigh impossible to consider Georges’ images and solely ‘read’ them as a commentary on the ‘American Dream’ and not be overwhelmed with how it’s a visual essay that is part of contemporary dialogue about the fate, if you will, of the United States, even if some of the images are over a decade old.

When I began considering this series, I was impressed with the way the photographs both inspired and intersected with socio – historical commentaries on the United States. Some of these are older, like de Tocqueville, or Howard Zinn‘s fine People’s History series (I will even admit to revisiting Eric Hobsbawm, and in a peripheral manner rereading parts of Margaret MacMillan’s Nixon in China: The Week That Changed the World). But others are more immediate, like Morris Berman‘s series on the United States that seemed to resonate the most with Georges’ images and intent.

And living in the Niagara region, or as a Canadian (though I suspect this applies to most people in the world observing) watching the decline of the American Empire with a front row seat (whether we want it or not, like attending a play where you might get splashed by the king’s blood when MacBeth does him in) we consider our Southern neighbour and their national imaginary as much, if not more, than our own….

Unlike some of the previous photographers featured – Jordano, Fairbairn, Green, many others – these scenes that Georges has presented us seem more sterile, more abandoned, less about a #rustbeltwonderland or ‘ruin porn’ aesthetic but are about actual ruination and catastrophe without an aesthetic barrier. Also a contrasting factor to when I respond to many artists, especially photographers, I feel that with Georges’ images I have so much to say, so many threads to pull together because of not just the evocative nature of his work but also the subject matter he’s exploring, that any words I say will inadvertently miss something important. Perhaps because I see Georges’ images as much as a historical document as they are art….

The words of Gore Vidal, whose commentary on ‘America’ was often clear if caustic, also came to mind : The world Julian wanted to preserve and restore is gone; the barbarians are at the gate. Yet when they breach the wall, they will find nothing of value to seize, only empty relics. The spirit of what we were has fled.

Amusingly – or more bleakly, edit as you will – that quote is from Vidal’s ‘bestseller about the fourth-century Roman emperor who famously tried to halt the spread of Christianity’ : that failed, of course. To quote another writer (putting words into the mouth of Caesar Augustus) “there are two futures, you see. Two ways it could go. In one future, the Romans sputter and flare like Greek fire, last a few hundred years and are gone — eaten from outside by barbarians, from inside by strange gods….”

Those bleak words of Vidal (and Neil Gaiman) mesh with the statement about the photographs from the artist :

Traveling across the United States, the French photographer Emmanuel Georges went in search of the American dream.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Georges’s recurring motifs—decaying façades of industrial buildings, garages, motels, movie theaters—become iconic images of American urban landscapes. Profoundly permeated by an omnipresent sense of melancholy, the empty streets, old cars, and abandoned gas stations are testimony to the end of the American dream.

I mentioned Morris Berman above. He’s written several books about the contemporary socio political sphere – specifically focused on decline – in the United States, with the most recent one being ominously titled Dark Ages America The Final Phase of Empire. It was published several years before Georges began his America Rewind series, so the current atmosphere in the United States is not surprising nor unpredictable to those paying attention and with a sense of history….

Berman’s words :

[Noam] Chomsky and [Michael] Moore would, metaphorically speaking, say that we have been raped by the corporate-consumerist-military establishment, but I suspect it was more like a seduction: if this was sex, it was definitely consensual.

We are in a state of advanced cultural disintegration, or what might be termed spiritual death. Given the emptiness, alienation, violence, and ignorance that are now pervasive in this country, it is hard to imagine where a recovery would come from. The self-correction theory is at least partly based on the popular reaction of an informed citizenry. In this regard, the nature of the American populace today is not a source of inspiration or hope.

In a bit of synchronicity, as I was working on this I was also having a conversation with Juliana D’Intino about her Connecting Rods work (which I’ve previously written about here). We were having a conversation about trying to create works and foster a conversation that is not just ‘ruin porn’ but that speaks to larger issues of social history and – as with Georges’ images – what is now lost, and likely never to be regained or recreated….

This raised the issue of the challenge when the aesthetic pleasure invoked by an image is in stark contrast to the concepts that inspired it. When I first encountered Emmanuel Georges’ America Rewind, I had this same concern. As I often do, I found the ‘right’ words by speaking in the voice of others, and I’ll end with a quote that I shared when I first reshared some of this artist’s images in the social media sphere. These are the thoughts of one of the characters in Atwood’s The Robber Bride, who is an historian with an affinity for choosing unique places to stand in considering the past:

Who cares? Almost nobody. Maybe it’s just a hobby, something to do on a dull day. Or else it’s an act of defiance: these histories may be ragged and threadbare, patched together from worthless leftovers, but to her they are also flags, hoisted with a certain jaunty insolence, waving bravely though inconsequentially, glimpsed here and there through the trees, on the mountain roads, among the ruins, on the long march into chaos.

I have selected a less positive place to stand than Atwood’s character : perhaps I am feeling my age, or not. But I am thinking of the T.S. Eliot line (from The Wasteland) of these fragments I have shored against my ruins…..For you know only a heap of broken images.

Many more images from this series – and more of Georges artwork – can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Barry Smith | What’s Your Stance? | 2024

June 29, 2024Barry Smith | What’s Your Stance? | 2024

Barry Smith’s exhibition What’s Your Stance? was on view at Mahtay Café & Lounge in downtown St. Catharines for the majority of the month of May 2024 and into early June. Smith’s exhibition was the 18th in my continuing series of shows in the space platforming visual artists of the Niagara Region that is soon to mark two years.

Smith is not – on social media or in life – shy about his own ‘stance’ and his own political views. I’ve known him for most of my time in Niagara, and the exhibition is a series of images of photographers taking photos that Smith has captured in the act. There’s a voyeurism to the work, but the nature of the installation in the downtown St. Catharines space also allows play and interaction between the ‘characters’ as they seem to be taking pictures of each other, or are looking at people and events unknown and unseen to us.

Smith’s statement : Everyone has their opinions. Whether it be in the social, political or religious sphere. Some are based on fact, some on faith, and some are emotional due to personal experiences, education and (sadly) social media.

We all have a point of view. Some are balanced, conservative or outright risky.

I see this in the way people take photographs. Some are amateurs, some hobbyists and others are professional – but everyone has their own stance.

What’s your stance?

To say we live in a time when contention and division between peoples’ respective stances is intense is an understatement. Smith, for example, is a vocal advocate for Palestine and against the ongoing genocide perpetuated by the state of Israel and her enablers on the international scene. In our shared community – and many, many others – this is a ‘stance’ many of us see as being a default one, while others choose to stand somewhere else….

I often see things – I choose to stand, in my interpretation – through the lens of the art world, both in Canada (that imaginary nation we live in) and the larger international discourses within that sphere.

With the current situation in the Middle East, fractures – splits that expose or exacerbate hypocrisy – are becoming harder to deny. The termination of Wanda Nanibush from her position at the AGO, for example, spearheaded by someone who will allude to how art should have a social conscience and challenge us, but ‘just not that way’, or more exactly NOT in a way they ‘disagree’ with is a fine example.

I’d offer another : as many of you know, I spent nearly two decades in Saskatchewan, a place rife with racism regarding Indigenous and Settler relations. I was deeply amused – and not surprised at all – at the hypocrisy of someone I had the lamentable experience to work with in the ARC spaces publishing an article with Galleries West, decrying what he saw as ‘rising antisemitism’ in the international art world. This same person was instrumental in attempting to silence and blackball me when I published numerous factual articles about the institutional racism at his employer, the University of Saskatchewan, and I thought when I saw his blinkered whining that perhaps he had begun to see that dehumanizing others is not something that can be contained to one space, and bleeds into others, especially when you legitimize it for your own ideology, thinking it is ‘unique.’

Recently I read an engaging article from ArtForum about the rise in protests in museums and in gallery spaces and the writer – Charlotte Kent – offered a number of ideas and writers that I’ve been researching since I read the piece about how cultural spaces are stakeholders and often consistent – if not eager – manufacturers of alibis for the status quo, whether that status quo be that only one ‘type’ of art is ‘actually art’ or that some people and ideas are simply a denkverbot (to paraphrase Žižek) : of them, ‘we’ are ‘prohibited to speak.’

But, as Kent asserts ‘Museums [and by extension what fills them, as art] have never not been political.’

…I suspect I told you more about ‘my stance’ with that tangential response to Smith’s work than about his work, but I also suspect Smith would be comfortable with that, in that I ‘answered’ his question.

Born in Scotland and raised in Niagara, Barry Smith has always had a flair for humour and wit which he often employs in the titles of his photographs and his compositions. A self taught photographer, Smith has found his own unique photographic style and approach, concerned with using natural light. Smith’s photographs come to life like a fresh painting on canvas.

A past St. Catharines Art Award nominee, Smith’s pictures can be found on display throughout Niagara at various art shows and galleries.

What’s Your Stance? A Selection of Photographs by Barry Smith was on view at Mahtay Café & Lounge in downtown St. Catharines in the Spring of 2024.

You can see more of his work at his IG here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Lowell Shaver | Process

April 12, 2024Dave Green | Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024

‘Time is nothing. We have our memory. In memory there is no time. I will hold you in my memory.

And you, maybe you will remember me too.’

(J.M. Coetzee, The Pole)

There is a Salvatore DiFalco quality to Dave Green’s photographs. It’s not just the scenes he presents us, but also the deep almost oily blacks and the grain of the film in many of his photographs. There is a physicality to these scenes, even when seen online : unsurprising, as he’s a photographer who is all about the photographic print and not just within the digital milieu of the present day, that has both its advantages and failings….

DiFalco is a writer and literary critic : I first encountered his fiction in a Canadian literary magazine in the early 2000s and this inspired me to seek out his book of short stories Black Rabbit & Other Stories.

These are urban stories, gritty snapshots of people who are frequently flawed and even, perhaps, a bit repellent. They take place in Toronto or Hamilton or even my own territory of the rust belt wonderland of Niagara, and several memorable ones that are situated in the latter two sites are as engaging as they are grotesque. The characters that inhabit DiFalco’s Black Rabbit (from Stories or Outside or Rocco or Alicia) could also populate some of the scenes that Green presents to us. Green’s work is not quite so dire or dour, nor quite as nihilistic, but his photographs do intersect with DiFalco’s world, whether literally (in his choice of places or his on the cuff captures of his immediate world) or through implication, with the unembellished frankness of Green’s photographs.

Death is also close in DiFalco’s stories : and the image that spurred this response to Green’s work – Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024 – also speaks to an affinity, if not a comfort, with stark endings and perhaps remembrance, perhaps not.

[gallery link="file" size="medium" ids="5984,5985,5986"]

From the artist’s site : Dave Green was born in Toronto (1963), Ontario and grew up in the small Southern Ontario city of Owen Sound. In the early 1980s he moved back to Toronto to study photography at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute (now Toronto Metropolitan University). He has worked as a house painter, a fibreglass worker, a photography technician and as an educator. He served as an instructor of photography at Ryerson’s Chang School of Continuing Education and has taught photography to youth affected by violence. He has travelled extensively throughout Canada, the United States and Europe, always with a camera.

The words of LP Farrell, from the introduction to Green’s book Personal (Dumagrad Books, 2017):

Looking at some of these photographs now, the prescience startles and the storefront facade windows, the tired barren highways, the sombre diners seem less a lament or nostalgic yearning for a different time, which is what I thought back then, than a crystal ball, sometimes literally reflecting, but often revealing a life marked by deep solitude. It is as though Dave saw, understood and then showed us what would happen to us all before life hit. Dave Green has photographed a world already disappearing like a picture not quite fixed, time remorseless and unrelenting. Time doing its thing.

———————————————————

This is a book of contrasts, the tension in the dialogue a whisper. Look here: youthful lust and yearning, women and lovers juxtaposed with landscapes busted and stripped down. Lust is a counterpoint to dilapidation. The tang of tungsten light in cavernous bars and then a street lamp, suddenly a votive light in a night sky over lovers like some crazy benediction. As if there was hope…

You can see more of Green’s work at his site here and his IG is here. Green is also represented by the MF Gallery.

If there is a reckoning, it is on the road. The photographer/passenger, the night and a beautiful woman at the wheel; a motorcyclist with a life garbage-bagged and strapped to the saddle of his BSA, maybe in flight. A bleak stretch of road ahead, road the arbiter. Love goes but the road always stays. Road, the redeemer.

LP Farrell, from the introduction to Green’s book Personal (2017)

They drove in silence, the landscape a work in charcoals and flaked quartz.

———–

What the fuck did he just do? He stopped running. He was out of breath.

He looked around him. He was standing nowhere.

(Salvatore DiFalco, from the short story Pink, from Black Rabbit & Other Stories)

I’ll end with how I feel an affinity for Green’s images of the rust belt wonderland : I could be looking at the streets I haunt in St. Catharines or Welland, and even the older images from the 1980s offer a run down weariness, a punky nostalgia, that I also remember from my youth in Niagara. I see echoes of Chris Killip or Tish Murtha, in the images of Dave Green as much as I see my own city, too.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

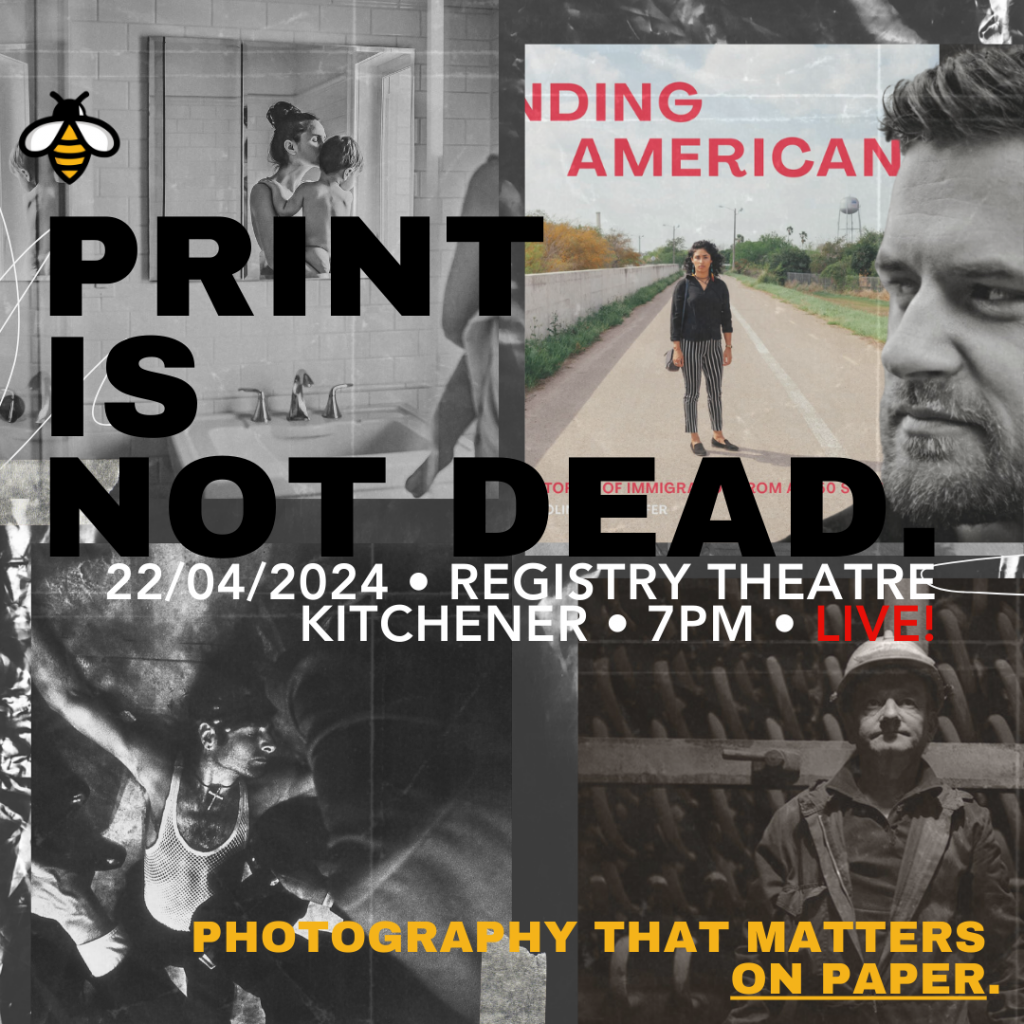

Print is Not Dead | Photography That Matters ON PAPER

April 12, 2024PRINT IS NOT DEAD| PHOTOGRAPHY THAT MATTERS ON PAPER

APRIL 22, 7PM

Registry Theatre, Kitchener, ON

Tickets HERE $15 (also available at the door)

Camera sale starts at 5:30PM @londonvintagecamerashow

In a world of fast image-heavy, screen-based storytelling, why do artist still see value in slow printed photographs? Is it still possible to become a published artist/photographer in Canada? Why are these photographers still concerned with the analog world?

Join local photographers, Colin Boyd Shafer @colinboydshafer , Robin Claire Fox @robinclairefox , and Karl Griffiths-Fulton for a panel discussion hosted by photoED Magazine’s publisher Rita Godlevskis @photoedmagazine to share the pros and cons of (now) rare analog experiences.

This live, in-person discussion will NOT be recorded and will exclusively share the behind the scenes stories of IRL humans that have successfully presented their work in high-quality PRINT.

Join us to learn more about how these local folks created their legacy works, and stick around for some qualitative peer-to-peer networking, connecting, and supporting these incredible (and rare) Canadian projects.

Stick around to review these artists works on paper. Photo books and magazines will be available for sale. Support incredible local photography IN PRINT.

SPECIAL BONUS! Ron and Maureen Tucker of the LONDON VINTAGE CAMERA SHOWS will be onsite, allowing us all to ogle and purchase their quality analog cameras and accessories Sale starts at 5:30 until 6:50 and then after the panel discussion.

Presented by curated. @thecovertcollective

Want more information? DM @thecovertcollective

Read More

Richard Misrach | The Desert Cantos series | 1979 – Present

April 22, 2024Richard Misrach | The Desert Cantos series | 1979 – Present

You look at landscape, but it’s not really landscape, it’s a symbol for our country, it’s a metaphor for our country.

(Richard Misrach speaking about The Desert Cantos)

If you’ve read my past writing, you won’t be surprised to know that I am a fan of the horror genre, both in terms of books and films. This is an underrated and often unfairly dismissed genre : not all horror is equal, of course, but that can be applied to any genre.

In Clive Barker’s film Lord of Illusions (based upon one of his short stories in the Books of Blood series), the opening sequence of the film has often been one of my favourite scenes in the occult horror tableaux. A cult with a charismatic leader who displays abilities that can only be magic is speaking to an entranced group of followers : their ‘headquarters’ is a long abandoned hotel in the California desert, overgrown and run down, a lone fragment shored against the ruins of a dream of prosperity now left unwanted and desolate, blanched and burned by the unflinching sun and sand. The establishing shots as we approach the derelict buildings are entrancing in their ruination, and the state of the cult members mirrors this sense of discarded abandonment….

If that seems somewhat ‘lowbrow’ then let us consider Cal Flynn’s book Isles of Abandoment | Life in the Post-Human Landscape and her chapter that is titled The Deluge and the Desert : Salton Sea, California, United States. This is a fine fit as many of Misrach’s images are of the fetid abomination known as the Salton Sea in Southern California.

It is a poison lake whispering sweet nothings. It promises cool succour, quenched thirst. Despite what I know of this shimmering mirage – despite the stink and the rot and the waste that surrounds it, despite the staring eyes of the dead and desiccating fish that litter its shrinking shores, despite the absence of vegetation – I can’t help but quicken my pace. I stumble through sucking mud towards this false vision, on and on until the muck is over my feet, and up to my ankles, and I am shin-deep in a warm broth that, when stirred, releases a draught so stagnant I can taste it.

Richard Misrach began this series in 1979 – nearly half a century ago – and “this ongoing project explores the southwest American desert landscape, and the impact of our human presence.” In that light, considering Misrach’s intent with this work, these images are not so much passive landscapes as active ones : these are scenes of the results of human action and remind me of my time on the Canadian Prairies and the plethora of abandoned oil wells, or the legacy of Uranium City in Saskatchewan, that speak to an attitude towards the environment that is not just an indicator of the Sixth Extinction but our unwillingness to consider the planet as something other than to be exploited and left when no longer of ‘use’, framed within a capitalist regime. As I’m engaged in my usual tangential style of criticism, I must also cite Richard Rodriguez’ essay The God of the Desert where he offers an aside that the three Abrahamic religions – being birthed in the desert – have an adversarial relationship to nature, instead of a more fostering, co dependent one….

Let us return to Clive Barker – specifically his book The Damnation Game (and considering some of the things I’ve mentioned already, citations about horror and hell may seem less forced, now. Ponder that ‘hell’ is a place we make, not a ‘place’ we ‘find’…which is perhaps what Misrach is documenting with these images) :

In a wasteland a few hundred yards from a highway overpass it finds a new incarnation: shabby, degenerate, forsaken. But here, where fumes thicken the atmosphere, minor terrors take on a new brutality.

It had once been an impressive building, and could have been again if its owners had been willing to invest in it. But the task of rebuilding and refurbishing such a large and old-fashioned hotel was probably financially unsound. Sometime in its past a fire had raged through the place, gutting the first, second and third floors before being extinguished. The fourth floor, and those above, were smoke-spoiled, leaving only the vaguest signs of the hotel’s former glamour intact.

From The International Center of Photography :

Richard Misrach was born in Los Angeles in 1949 and received a BA in psychology from the University of California, Berkeley. He helped popularize large format color photography in the 1970s and 80s and is best known for Desert Cantos, his ongoing study of the American desert and man’s relation to it. The project presents a variety of images, from traditional landscapes to the space shuttle landing, which Misrach considers a singular work, with each canto acting as the equivalent of a (book) chapter heading. Misrach also works in a social documentary style, which can be seen in his Louisiana photographs of Cancer Alley, the corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. In addition, he also has taken pictures of the desert sky; the Golden Gate Bridge; the beaches, water, and jungles of Hawaii; Stonehenge; and the Pyramids.

Misrach’s photographs can be found in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Museum of Modern Art; the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among others.

More about Richard Misrach’s photographs and aesthetic (both the Desert Cantos series and other works) can be enjoyed here and here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Dave Green | Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024

April 12, 2024Dave Green | Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024

‘Time is nothing. We have our memory. In memory there is no time. I will hold you in my memory.

And you, maybe you will remember me too.’

(J.M. Coetzee, The Pole)

There is a Salvatore DiFalco quality to Dave Green’s photographs. It’s not just the scenes he presents us, but also the deep almost oily blacks and the grain of the film in many of his photographs. There is a physicality to these scenes, even when seen online : unsurprising, as he’s a photographer who is all about the photographic print and not just within the digital milieu of the present day, that has both its advantages and failings….

DiFalco is a writer and literary critic : I first encountered his fiction in a Canadian literary magazine in the early 2000s and this inspired me to seek out his book of short stories Black Rabbit & Other Stories.

These are urban stories, gritty snapshots of people who are frequently flawed and even, perhaps, a bit repellent. They take place in Toronto or Hamilton or even my own territory of the rust belt wonderland of Niagara, and several memorable ones that are situated in the latter two sites are as engaging as they are grotesque. The characters that inhabit DiFalco’s Black Rabbit (from Stories or Outside or Rocco or Alicia) could also populate some of the scenes that Green presents to us. Green’s work is not quite so dire or dour, nor quite as nihilistic, but his photographs do intersect with DiFalco’s world, whether literally (in his choice of places or his on the cuff captures of his immediate world) or through implication, with the unembellished frankness of Green’s photographs.

Death is also close in DiFalco’s stories : and the image that spurred this response to Green’s work – Self portrait in the window of the Greenwood Cemetery chapel, Owen Sound, 2024 – also speaks to an affinity, if not a comfort, with stark endings and perhaps remembrance, perhaps not.

From the artist’s site : Dave Green was born in Toronto (1963), Ontario and grew up in the small Southern Ontario city of Owen Sound. In the early 1980s he moved back to Toronto to study photography at Ryerson Polytechnical Institute (now Toronto Metropolitan University). He has worked as a house painter, a fibreglass worker, a photography technician and as an educator. He served as an instructor of photography at Ryerson’s Chang School of Continuing Education and has taught photography to youth affected by violence. He has travelled extensively throughout Canada, the United States and Europe, always with a camera.

The words of LP Farrell, from the introduction to Green’s book Personal (Dumagrad Books, 2017):

Looking at some of these photographs now, the prescience startles and the storefront facade windows, the tired barren highways, the sombre diners seem less a lament or nostalgic yearning for a different time, which is what I thought back then, than a crystal ball, sometimes literally reflecting, but often revealing a life marked by deep solitude. It is as though Dave saw, understood and then showed us what would happen to us all before life hit. Dave Green has photographed a world already disappearing like a picture not quite fixed, time remorseless and unrelenting. Time doing its thing.

———————————————————

This is a book of contrasts, the tension in the dialogue a whisper. Look here: youthful lust and yearning, women and lovers juxtaposed with landscapes busted and stripped down. Lust is a counterpoint to dilapidation. The tang of tungsten light in cavernous bars and then a street lamp, suddenly a votive light in a night sky over lovers like some crazy benediction. As if there was hope…

You can see more of Green’s work at his site here and his IG is here. Green is also represented by the MF Gallery.

If there is a reckoning, it is on the road. The photographer/passenger, the night and a beautiful woman at the wheel; a motorcyclist with a life garbage-bagged and strapped to the saddle of his BSA, maybe in flight. A bleak stretch of road ahead, road the arbiter. Love goes but the road always stays. Road, the redeemer.

LP Farrell, from the introduction to Green’s book Personal (2017)

They drove in silence, the landscape a work in charcoals and flaked quartz.

———–

What the fuck did he just do? He stopped running. He was out of breath.

He looked around him. He was standing nowhere.

(Salvatore DiFalco, from the short story Pink, from Black Rabbit & Other Stories)

I’ll end with how I feel an affinity for Green’s images of the rust belt wonderland : I could be looking at the streets I haunt in St. Catharines or Welland, and even the older images from the 1980s offer a run down weariness, a punky nostalgia, that I also remember from my youth in Niagara. I see echoes of Chris Killip or Tish Murtha, in the images of Dave Green as much as I see my own city, too.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Clarence John Laughlin | Southern Gothic

March 12, 2024Clarence John Laughlin (1905 – 1985) | Southern Gothic

Laughlin was a New Orleans photographer : he’s best known for his black and white, sometimes uncanny and disquieting images of the Southern United States. Considering the ethereal and dream like quality of many of his scenes, he’s sometimes spoken of as the father of American Surrealism. In considering his photographs, the ‘original’ definition of Surrealism from André Breton was to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality.” Less pretentiously (Frida Kahlo did refer to Breton as being among the ‘art bitches’ of Paris, whom she disdained, ahem), in the work of Laughlin, one can see that he was attempting to both re interpret and define his own memories and experiences of a site, while also employing the place and people within it, that is rife with contested narratives.

I tried to create a mythology from our contemporary world. This mythology — instead of having gods and goddesses — has the personifications of our fears and frustrations, our desires and dilemmas.

(Clarence John Laughlin)

For those unfamiliar : ‘Southern Gothic is an artistic subgenre…heavily influenced by Gothic elements and the American South. Common themes of Southern Gothic include storytelling of deeply flawed, disturbing, or eccentric characters who may be involved in hoodoo [or the large sphere of the occult], decayed or derelict settings, grotesque situations, and other sinister events relating to or stemming from poverty, alienation, crime, or violence.’ (from here)

As darkness set in, the mist drifted off the deep acreage of sugarcane that flattened back to the surrounding slough and mire. Blooming loblolly bushes, palmettos, and thick fields sprouting a type of flower he’d never seen before filled the evening air with an assertive but sweet fragrance.

The Nail family lived in an antediluvian mansion that had been built long before the separation of states. He saw where it had been rebuilt after Civil War strife and he could feel the dense and bloody history in the depths of the house. He glanced up at a row of large windows on the second floor and saw six lovely pale women staring down at him.

————————

A tremendously wide stairway opened to a landing where colonnades rose on either side abutting the ceiling. He could see the six sisters huddled together at the banister curving down from the second floor, all of them watching him, their hair sprawled over the railing. He waved, but only one of them responded, lifting her hand and daintily flexing her fingers.

(Tom Piccirilli, Emerald Hell)

The book I quote above takes place primarily in Louisiana – where the artist who’s the focus of this essay was born, and a place, whether in terms of New Orleans (his birthplace) or the greater Southern Reach (a term I borrow from another author), that defined his aesthetic. In that book, there are many dark characters that are pervasive within Southern Gothic horror that’s a wide genre, one which I’ve been quite interested in of late. The aforementioned Nail family’s daughters suffer under a ‘curse’ where they cannot speak, and seem to move about the massive manse like apparitions, veiled and almost insubstantial, like a breeze accentuated by their long dresses and hair (like so many lamenting female ghosts of the South, and elsewhere).

Another player in Emerald Hell is known only as ‘the walking darkness’ or ‘Brother Jester’ : a former evangelical preacher who, after surviving an attempt made on his life, wanders the highways and byways of the state, leaving human wreckage in his wake. A later day incarnation of Robert Mitchum’s ‘man of god’ in the film Night of the Hunter (1955), perhaps. I am also reminded of some of the desolate – but drenched in histories and stories, almost like a stain on the ground – landscapes from the first season of True Detective, which is another iteration of the essence of the Southern Gothic.

One could imagine Laughlin’s images as characters and tableaux for such a chronicle. In this sense, Laughlin is a storyteller, an historian, just like Michael Lesy, who took us on a Wisconsin Death Trip…

Ghosts exist for a purpose. Unfinished business, delayed revenge, or to carry a message. Sometimes the dead can go to a lot of trouble to bring a desperate warning of some terrible thing that’s coming.

Whatever the reason, don’t blame the messenger for the message.

(Simon R. Green, Voices from Beyond)

I attempt, through much of my work, to animate all things—even so-called ‘inanimate’ objects–with the spirit of man….the creative photographer sets free the human contents of objects; and imparts humanity to the inhuman world around him.

(Clarence John Laughlin)

Born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, Laughlin had a difficult childhood, and this – in tandem with his ‘southern heritage’ and literary interests – are touchstones for his work. The family moved to New Orleans in 1910 after further economic hardship, with his father working in a factory in the city. A quiet, introverted child, Laughlin had a close relationship with his father whose encouragement – especially in terms of Laughlin’s interest in literature – was important to his development as an artist. His father’s death in 1918 affected him greatly : the dark, funerary, epitaphic nature of much of his work, perhaps, echoes this loss.

Laughlin never completed high school, but was a “highly literate man. His large vocabulary and love of language are evident in the elaborate captions he later wrote to accompany his photographs.

Laughlin discovered photography when he was 25 and taught himself how to use a simple 2½ by 2¼ view camera. He began working as a freelance architectural photographer and was subsequently employed by agencies as varied as Vogue Magazine and the US government. Disliking the constraints of government work, Laughlin eventually left Vogue after a conflict with then-editor Edward Steichen. Thereafter, he worked almost exclusively on personal projects utilizing a wide range of photographic styles and techniques, from simple geometric abstractions of architectural features to elaborately staged allegories utilizing models, costumes, and props.” (from here)

From the High Museum of Art in Georgia (the accompanying text for a retrospective of Laughlin’s work) : “Known primarily for his atmospheric depictions of decaying antebellum architecture that proliferated his hometown of New Orleans, Laughlin approached photography with a romantic, experimental eye that diverged heavily from his peers who championed realism and social documentary.”

More about his work and life can be enjoyed here and here : and perhaps, while perusing these images, consider listening to another Southerner – Johnny Cash – and his song The Wanderer, that also offers (ironically, considering the title) a place to stand, intertwined with histories both personal and more public, when considering the photographs of Clarence John Laughlin.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Sandy Fairbairn | ART, Road Closed | Welland, April 5 2014

January 19, 2024Sandy Fairbairn | ART, Road Closed | Welland, April 5 2014

Four years ago, just as Covid – 19 was beginning to move across the world, an exhibition of Sandy Fairbain‘s artworks that I curated at AIH Studios in Welland opened. These selections from the photographer’s extensive archive were focused upon the city of Welland and were collectively titled Welland : Times Present Times Past. Originally planned to run from February 15th to March 15th 2020, lockdowns and access became an issue, but I take joy in a local writer describing it as one of the most important exhibitions in that city, of the decade. There were also works that acknowledged the major role that Welland played in the history of labour rights in Canada, that were more sculptural, but that’s a story for another time (or seek out the book Union Power : Struggle and Solidarity in Niagara that is a fine history of the space, before we acquiesced to the ‘dogma’ of ‘trickle down economics’ and the liars Mulroney, Thatcher and Reagan, ahem).

This image was one of the more unique ones in that show, differing formally from Fairbairn’s usual straight on shots of buildings and edifices, reminiscent of ‘mug shot architecture’, if you will. But perhaps it might be better described as ‘morgue’ photos, as when we hung the show there were many captures of the same space, from decade to decade, and many times the sites were now demolished and empty….

I must add that as COVID took hold, I was in Welland for a longer time than I had planned to be there, with Fairbairn’s exhibition, and with the vagaries of lockdown I got to know the city late at night or early in the morning, a sense of itself that is not the ‘official’ kind.

Conceptually, this image offers both amusement and cynicism simultaneously. As someone who is soon to mark a decade of being part of the cultural community of Niagara, I could also add that it has resonance in terms of endeavours both planned and aborted, envisioned and stuttered, that have defined [and deformed] the cultural landscape of not just the city of Welland, but the larger Niagara Region.

So like any fine artwork, my interpretation of it changes depending upon when I see it, and the experiences I bring to it, and thus it shifts just as I do (perhaps in tandem, perhaps in opposition). To flip back to a more literal meaning from a conceptual one, my own attitudes about art initiatives within the space of Niagara have also changed, and spurred my decision to feature this work.

One hopes and works to foster artistic and cultural initiatives but finds the road closed, if you will. There are a variety of talks about ‘cultural revitalization plans’ in Niagara, but as this is the space that let a nationally recognized public art gallery go, with barely a whimper and now ignorant celebration of the ’boutique hotel’ that has taken it’s place, I shall reserve my enthusiasm…..but, to offer a positive point as we end, the push to have an Art Gallery of Welland is also moving forward, slowly but surely, and that effort is not without reward. As Sandy Fairbairn grew up in Welland (oh, the stories he’s shared with me, that I enjoy and enlivened some of his images from the aforementioned AIH exhibition), that is a space that might, soon, host more of his photographs like this one.

Not all roads are closed forever.

More of Sandy Fairbairn’s work can be seen here and here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Jeff Brouws | Night Window, Los Angeles, California, 2000

December 29, 2023Jeff Brouws | Night Window, Los Angeles, California, 2000

In the Far West, where Brigham Young ended up and I started from, they tell stories about hoop snakes.

When a hoop snake wants to get somewhere—whether because the hoop snake is after something, or because something is after the hoop snake—it takes its tail (which may or may not have rattles on it) into its mouth, thus forming itself into a hoop, and rolls.

Jehovah enjoined snakes to crawl on their belly in the dust, but Jehovah was an Easterner. Rolling along, bowling along, is a lot quicker and more satisfying than crawling. But, for the hoop snakes with rattles, there is a drawback. They are venomous snakes, and when they bite their own tail they die, in awful agony, of snakebite. All progress has these hitches. I don’t know what the moral is. It may be in the end safest to lie perfectly still without even crawling. Indeed it’s certain that we shall all do so in the end, which has nothing else after it. But then no tracks are left in the dust, no lines drawn; the dark and stormy nights are all one with the sweet bright days, this moment of June—and you might as well never have lived at all.

(Ursula K. Le Guin, from her essay It was a dark and stormy nigh ; or, why are we huddling about the campfire?, 1979)

A number of the images that I share in the main page for this post are also from Brouws’ American West series (1990 – 1993) and the Highway | Approaching Nowhere series. Many of Brouws’ series seem to bleed into each other, or one body of work grows into the next in a manner that does not so much interrupt his ideas as expand them.

I have a certain affinity for abandoned and derelict spaces. I do live in the rust belt wonderland of Niagara, and before that a similar zone in Windsor and Detroit (hence my appreciation of Dave Jordano‘s fine photographs), and my time on the Canadian prairies (with ghost towns in ‘next year’s country’, as captured eerily and evocatively by Danny Singer, for example) fed that interest in an overlapping manner. Brouws’ aesthetic is akin to some past Curator’s Picks I’ve featured : The Great Texas Road Story perhaps being the most immediately similar. But Brouws’ works are less despairing, with the frequency of the neon inviting glow amidst the wastelands, but like many other artists whose work I’ve featured, historical and social themes and concerns are informed by, and informing, his scenes.

“Feelings of isolation colour my photographs – that’s what you’re sensing. It’s fascinating: what’s in your mind, heart and soul gets telegraphed onto the film plane and embedded in the photograph. It can’t be avoided.”

From the Robert Koch Gallery :

“Jeff Brouws photographically explores the American cultural landscape in its myriad of facets. A self-described “visual anthropologist” with a camera, Jeff Brouws utilizes a constructed narrative and typological approach in the making of his work. Over a span of thirty plus years, Brouws has employed a diversity of themes in his work: the American highway, the franchised landscape, deindustrialized inner city zones, as well as riffing on and re-examining bodies of work by luminary artists such as Ed Ruscha, and Bernd and Hilla Becher. Brouws captures the unique cultural experience of Americana and its iconography, visually documenting a vibrant travelogue through the half-experienced, half-remembered landscape of America’s fading culture. Directing his lens toward these temporary obsolete and abandoned sites of American consciousness, he powerfully transforms images of history and dereliction into contemplative and at times humorous commentary on the collective and expressive experience of the American landscape.”

An insightful conversation with the artist can be enjoyed here. When I first encountered Brouws’ work – the primary image in this essay Night Window, Los Angeles, California, 2000 – the quote from Le Guin that opens this meditation on his work came immediately to mind. It’s all about telling stories, some of which are quieter than others, some of which are on the verge of being forgotten and some that we may never have considered. The term ‘into the west’ has connotations both positive and negative, but that is just life, and history, and Brouws’ images encapsulate all these contradictions with an eye for beauty in what might be banal, but definitely resonates with the viewer on multiple levels.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Adrianna Ault & Raymond Meeks | Ohio Farm Auction

December 11, 2023Adrianna Ault & Raymond Meeks | Ohio Farm Auction

The crops we grew last summer weren’t enough to pay the loans

Couldn’t buy the seed to plant this spring and the Farmers’ Bank foreclosed

Called my old friend Schepman up, to auction off the land

He said, “John it’s just my job and I hope you understand”

Hey, calling it your job ol’ hoss, sure don’t make it right

But if you want me to I’ll say a prayer for your soul tonight

(John Mellencamp, Rain on the Scarecrow)

One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever. (Ecclesiastes 1:4, KJV)

There’s a memento mori quality to the scenes from the Ohio Farm Auction series. This may be an interpretation informed by several of the other bodies of work by Adrianna Ault (such as her series Levee which led me to the collaborative Ohio Farm Auction series), that are permeated by a sense of mortality and remembrance, as expressed in her writings about those images.

Though these images are not completely empty of people, the more striking and – unsurprisingly – starker moments that stay with you have no figures within them, though their absence and implication is powerful. The line I quote above, in response to this work came to mind immediately upon seeing the Township photos. Mellencamp’s album was a series of laments for a way of life lost (perhaps taken away or relinquished), as the world moves on (this last being closest, I feel, to the artists’ position here, with a gentle consideration of family history and generational change. Township reads more about releasing than resistance..)

The biblical quote came to me in a more indirect manner. Having recently read George Stewart’s post apocalyptic book Earth Abides (from 1949, so it ages poorly, in many ways – or this is perhaps a corolary to the ‘change’ implicit in the story presented in Ohio Farm Auction, of a time to gather and a time to discard), the ideas, again, of what is lost and our – humanity’s – place in the larger narrative of the earth was a further consideration when I engaged with these photographs…

The words of Adrianna Ault, speaking of this collaboration with Meeks (one of a number they’ve done) :

“These photographs were taken one February day in a rural township in Ohio. My partner, Raymond Meeks, and I photographed and watched as all the possessions of my family’s farm was auctioned to the highest bidder. Photographing served as a testimony to the life and work of over one hundred years of farming in my family. This work was published as a collaboration with Tim Carpenter and Brad Zellar in the book Township published by TIS books and later nominated for the 2018 Kassel Fotobookfestival Award.”

That collection of words and photographs has been described as a “careful deliberation on transience and the ultimate meaning of a way of life in the Midwest.”

More of Ault’s work can be seen here and more of Meek’s work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments