In: photography

Artem Humilevskyi | Untitled from the series Giant, 2020 – 2021

January 13, 2023Artem Humilevskyi | Untitled from the series Giant, 2020 – 2021

F. once said: At sixteen I stopped fucking faces. I had occasioned the remark by expressing disgust at his latest conquest, a young hunchback he had met while touring an orphanage. F. spoke to me that day as if I were truly one of the underprivileged; or perhaps he was not speaking to me at all when he muttered: Who am I to refuse the universe? (Leonard Cohen, Beautiful Losers)

Many years ago – as in decades – I fulfilled a dream I had of being a Ramboy in the artist Evergon’s photographic series Ramboys: A Bookless Novel. These were primarily nude portraits, and though it was a wonderful experience it is somewhat intimidating to be so exposed both in the moment and with the photograph afterwards (even when young and relatively fit).

I used to joke that I hoped that no other images of myself might proliferate, so that when I was arrested for some crime, newspapers and media would need to use that image, to much amusement and potential scandal (for others, not me. I would later work with Evergon again, ‘playing’ Puck in his photographic iteration of A Midsummer Night’s Dream).

But there is always a vulnerability in self portraiture, whether you’re bare or baring an aspect of yourself. This is present not just in the creation of the work, but also in considering how those images might be received.

That courage in the face of vulnerability – real or imagined, potential or expected – is what initially engaged me about Artem Humilevskyi’s series GIANT.

“Before he released GIANT, a series of self-portraits, Artem Humilevskyi’s finger hovered over the “publish” button for six hours. It was a personal project that required him to bare all, both physically and philosophically, and he had no way of knowing how people might react. In the end, it was worth the risk. “Hitting that button was a decisive step in the project,” he says. “When I did it, I realized that nothing happened. No one threw stones at me; all the experiences I had dreaded lived only in my head.””

“GIANT is a two-year project that began in March 2020. The collection is about understanding and accepting yourself as a human being. It is not necessarily body positive or a call to change the norms or the aesthetics of the body. It is a way of denying the sexualization of the human body, it’s about accepting yourself as an individual and being able to make friends with yourself; a way to stop hating yourself for your imaginary flaws. It has not been easy because real freedom from external and internal condemnations is not possible without a fight. Each photograph is a new step on this path to this freedom. The body as a subject in the project is not important, it can be an interpretation of any of the qualities that you dislike or hate. Reconciliation with them is the only way to become a complete person who understands that all our troubles are only inside our minds. Love yourself for what you used to hate and you will feel true freedom.” (from here)

More of this series can be seen here.

IG: @humilevskiy

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Romina Ressia | Woman with a Water Pistol, 2014

January 6, 2023Romina Ressia | Woman with a Water Pistol, 2014

Most of the writing around Ressia’s photographs talks about absurdity and anachronism: perhaps that’s because she appropriates form and redefines meaning in a manner that challenges art historical tropes around gender and relevance. Meticulously executed, her ‘portraits’ have a gravitas on the one hand, but then this is broken by elements that can’t help but amuse (though her people never crack a smile, with eye contact that might wilt any irreverence from the viewer).

There is a hint of dourness to the woman who is the player in this series, and many others, having a heavy handed seriousness that is then fractured by the various objects her subjects are brandishing that seem silly and puerile.

Bluntly, Messia’s Woman with a Water Pistol looks like she’s had just about enough of you, young man, and unless you want to be sprayed with water – disciplined like an unruly, disobedient cat – you’d best behave. You shan’t be told again.

A bit flippant perhaps. But consider the [still, uninterrupted] proliferated misogyny in Western art history [or contemporary art] of women as object, or demure commodity, or the validation / apologia of rape as seen with Europa or the Sabine women or ‘Susannah and the Elders’ (and so, so many others). Consider that in (recently done) 2022 we’ve seen groups of women around the world make it clear that they have had *quite* enough and my interpretation is not without consideration….

This image is part of a larger series titled How would have been Childhood? with the same figure in them all, her unimpressed body language acting as a unifying aspect of the artworks. Birthday hats, costumes, balloons – nothing seems to inspire joy, here. When I first encountered this series online, a birthday party that no one was enjoying – if anyone even came, besides the ‘star’ of the series – can be forgiven for being an initial impression….

“Romina’s art cleverly initiates dialogue on important contemporary social issues through the striking use of anachronistic tropes juxtaposed with mundane and banal elements of modernity. Indeed, the influence of classical artists like Da Vinci, Rembrandt and Velazquez is instantly recognizable in the palettes, textures, ambiance and scenes captured in Romina Ressia’s works, bequeathing them an air of familiarity which only serves to highlight the contradictory and sometimes confrontational presence of objects of modernity such as cotton candy, bubble gum, microwave popcorn and Coca Cola.

The theatrical absurdity in her pictorial compositions, which combine stylistic elements of Renaissance paintings and Pop art, and the dissonance of the stark contradictions captured therein have a surprising clarity, making for an honest critique through visual dialogue of received notions of modernity. In this sense, Romina succeeds in achieving her artistic intent which is not to recreate or refer to the past but to establish a frame within which to interrogate the perceived evolution and progress of society especially in respect to the role and identity of women.” (from here)

If you’re doltish enough to suggest ‘she’d look better if she smiled’, don’t be surprised if you get soaked – deservingly.

More of Romina Ressia’s evocative – if a bit disquieting – work can be seen here.

Her Instagram is @rominaressia

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Nadav Kander | Chernobyl, Half Life, 2004

December 23, 2022Nadav Kander | Chernobyl, Half Life, 2004

I drink to our ruined house,

to the dolor of my life,

to our loneliness together;

and to you I raise my glass,

to lying lips that have betrayed us,

to dead-cold, pitiless eyes,

and to the hard realities:

that the world is brutal and coarse,

that God in fact has not saved us.

(Anna Akhmatova, I drink to our ruined house…, 1934)

I am old enough to remember when Chernobyl happened, and like many events it has become larger in the public consciousness as the years pass. In some ways, my time as a teenager had numerous events that have shaped history, as I also remember being in my high school history class and discussing the fall of the Berlin Wall, which happened a few years later.

One can’t speak of the fall of the Soviet empire without citing Chernobyl: Emmanuel LePage, in the graphic novel Springtime in Chernobyl (2012), asserts that ‘the disaster in Chernobyl is the first nail in the coffin of the Soviet Bloc.’ It is not unintentional, I think, that this metaphor is employed after an earlier passage where a widow describes the elaborate entombment of her husband’s irradiated body, like a pharaoh’s sarcophagus to hell instead of heaven…

It has become a touchstone for many artists in a variety of mediums. Some use this disaster as a means to a larger conversation. Others remind us of Stephen King’s Blind Wille reminiscing about his time in Vietnam (from Hearts in Atlantis), admitting it had much to “teach him, back in the years before it became a political joke and a crutch for hack filmwriters.”

In writing about his series Chernobyl, Half Life (2004), Nadav Kander offers the following:

“Reactor No.4 at Chernobyl’s Nuclear Power Station exploded in 1986 leaving the surrounding area uninhabitable for many hundreds of years to come. It happened to be the 20th Anniversary since the explosion when I gained access as an artist to visit Chernobyl, photographing the deserted spaces in what was once a model Soviet City.

Home to more than 40,000 people, the apartments, schools and hospitals that were hastily left following the controversial evacuation are stark reminders of past lives, leaving a disturbing sense of quiet. An uneasiness that I had never previously experienced.

There is a great beauty in a very real way to be found as the poignancy of human suffering almost hangs in the air. I found myself with a familiar feeling; best described as the feeling when walking through an overgrown cemetery on a drizzly day, but what I was looking at was far from familiar.

Having grown up with stories of relations of mine including my Father with his family that were suddenly evacuated during the second world war, I could not help but feel quite profoundly shocked as well and at the same time wonder what it must have felt like to suddenly leave your home and be transported to an unknown destination, suspecting that the near future would probably bring severe ill health due to being exposed to large doses of radiation. Little is known about the radio-active affects on the people of this city as the population were dispersed all over Russia. If there was a gathering of data by the government, it was never reported.”

I’ve selected a few of the images from this series, and most of them are focused upon spaces that would be set aside for children. Kindergarten Golden Key, Sleeping Room evokes a memory of visiting Spring Hurlbutt’s The Garden of Sleep / Le Jardin du Sommeil, which was also a contrasting beautiful space to meditate upon the death and loss of children, and both provide a focus for grief.

With work like this, there is a danger of the glorification of destruction: what one of my critical brethren has called ‘ruin porn.’ Kander, however, with his choice of sites has privileged the people – their absences are very clear, in the scenes he depicts – so that amidst all of the geo political discourse, humans and our humanity is not forgotten, willfully or otherwise….

Akhmatova’s words from half a century earlier act as a fine narration of these images: as an addendum to this pick, I’d also suggest the series Chernobyl, as it also focused upon the reality of Pripyat residents, situated within a larger historical narrative (much like Ahkamatova’s poems do).

And, with Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, some historians are reminding us of past events like the Holodomor – and in some ways, Chernobyl fits within this – where an ’empire’ exhibits cruelty and disregards humanity, whether through malevolence or ignorance, and sometimes I see Chernobyl through this lens, as well….

There is a surfeit of cultural commemoration or interpretation of this event and some is better than others. Kander’s work is quietly unsettling, even after all these decades.

More of this series can be seen here.

IG: @nadavkander

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Elena Chernyshova | Days of Night / Nights of Day, 2012-2013

December 8, 2022Elena Chernyshova | Days of Night / Nights of Day, 2012-2013

‘I was with my people then, there, where my people, unfortunately, were.’

(Anna Akhmatova, Requiem, 1935 – 1961, writing of her times in the soviet gulag)

When I lived in Saskatoon, an acquaintance who’d spent time in Eastern Europe once commented that that city in winter was like Siberia, but without the cachet of being that place (which exists as much in our imaginations as it does in reality, one might say – as a ‘great part of the imagination of the world is attached to that site’), nor with architecture that was anything but a failed brutalism (this was during a period with the ‘economic boom’ in Saskatoon where a number of heritage buildings were lost and the banal taupe of others rose like mottled angular tumours….)

Elena Chernyshova’s work is aesthetically stunning: not just for the evocative quality of the images, but also for the scenes they present to us, that seem to blend exotica and danger, a chronicle of sites that remind us of the irrelevance of humanity in the face of nature.

But her notes and comments bring the human element back, as this is not just a ‘pretty’ image, but a site of – of course – contested narratives, that looks back to the history of the USSR and some of the ideas of industrialization and ‘progress’ that have human costs.

Chernyshova’s own words are a powerful adjunct to her lens: “Days of Night / Nights of Day is about the daily life of the inhabitants of Norilsk. Norilsk is a mining city, with a population of more than 170,000. It is the northernmost city (100,000+ people) in the world. The average temperature is -10° C and reaches lows of -55° C in the winter. For two months of the year, the city is plunged into polar night when there are zero hours of sunlight.

The entire city, its mines and its metallurgical factories were constructed by prisoners of the nearby gulag, Norillag, in the 1920s and 30s. 60% of the present population is involved with the city’s industrial processes: mining, smelting, metallurgy and so on. The city sits on the world’s largest deposit of nickel-copper-palladium. Nearly half of the world’s palladium is mined in Norilsk. Accordingly, Norilsk is the 7th most polluted city in the world.

This documentary project aims to investigate human adaptation to extreme climate, environmental disaster and isolation. The living conditions of the people of Norilsk are unique, making them an incomparable subject for such a study.”

Chernyshova offers the following about the image of monumental architecture (with a blue suffusing light): The construction plan of Norilsk was established in 1940, by architects imprisoned in the nearby Gulag. The idea was to create an ideal city. The most “ancient” buildings are constructed in the Stalinist style. The next step of construction happened in the 60s, when the prevailing method in the USSR was to use pre-built panels.

Her other writings also allude to the disputed, if not adversarial, stories that meet and intersect in Days of Night / Nights of Day. The scene with the car and hazy clouds the colour of sulfur has the following notation: In the summer, there is a period when the sun doesn’t go under the horizon. This continues from the end of May till the end of July. It is accompanied by good weather and pleasant temperatures. Around 3 am, while the city sleeps, it is still illuminated by the sun. The city seems like a ghost town, emptied of its inhabitants.

One of the images I’ve included from Chernyshova’s series is unlike the others: and its difference helps to offer insight into the whole. Again, Chernyshova’s voice must be borrowed: Anna Vasilievna Bigus, 88, [who] spent ten years of her youth in the Gulag. At age 19, she was separated from her family and sent into the Arctic Circle. “The only joy we could have in Gulag was singing. We sang a lot. And this gave us the strength to survive…” Her daughter became a music teacher and her grandchildren sing in opera.

The complete series (produced with the support of The Jean-Luc Lagardère Foundation) can be seen here and a feature from LensCulture (where Chernyshova offers some words about many of the images I’ve shared here, that offer more nuance and depth to her vision) can be enjoyed here.

Elena Chernyshova’s site

@elena.chernyshova.photography

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

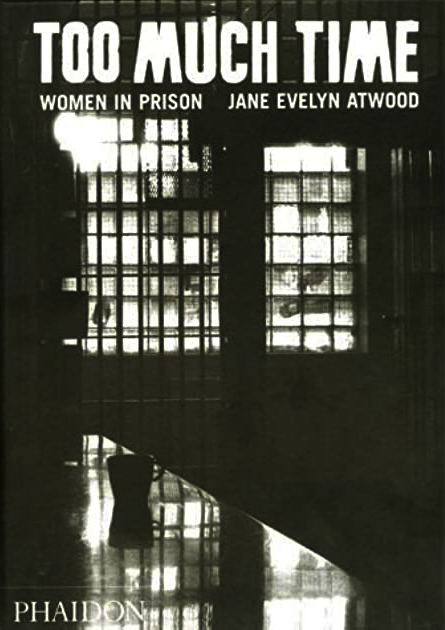

Jane Evelyn Atwood | TOO MUCH TIME: WOMEN IN PRISON, 2000

November 25, 2022Jane Evelyn Atwood, TROP DE PEINES: FEMMES EN PRISON, 2000, Éditions Albin Michel, Paris, France. (OUT OF PRINT)

Jane Evelyn Atwood, TOO MUCH TIME: WOMEN IN PRISON, 2000, Phaidon Press Ltd., London, England. (OUT OF PRINT)

“Curiosity was the initial spur. Surprise, shock and bewilderment soon took over. Rage propelled me along to the end.”

Too many times – and I’m sure I’m not alone in this – I have heard some well meaning dilettante assert that ‘art should be about beauty’ or ‘should only uplift us.’ In terms of that space where photography intersects with ideas of art and documentary – and not to mention history – something that comforts you is most likely wrong, if not simply pablum. When I’m sharing images on social media, there are some photographers I hesitate to post works from (as photography still carries the weight of being more ‘real’, thus can ‘offend’ as well as see yourself banned from those platforms): Gilles Peress is one of those, for his unflinching lens in places from Rwanda to the former Yugoslavia (“I don’t trust words. I trust pictures”), Gordon W. Gahan (specifically his images of the Vietnam War), Donna Ferrato (I was lucky enough to experience her groundbreaking series Living with the Enemy decades ago, in Windsor) or Martha Rosler (her House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home works that had their genesis in response to the Vietnam War (c.1967–72) but that she ‘revisited’ in 2004 and 2008, ‘updating’ them to Iraq and Afghanistan).

But the text I’ve selected for a Library Pick is something that is not ‘there’ but ‘here’, and in that respect is often – easily, repeatedly – ignored.

Jane Evelyn Atwood’s “monumental work on female incarceration, published in both French and English, took Atwood to forty prisons in nine different countries in Europe, Eastern Europe, and the United States. The access she managed to obtain inside some of the world’s worst penitentiaries and jails, including death row, make this ten-year undertaking the definitive photographic work on women in prison to date. Extensive texts include interviews with inmates and prison staff as well as Atwood’s own reminiscences and observations. The prize-winning photos in this book, including the story of an incarcerated woman giving birth while handcuffed, established Jane Evelyn Atwood as one of today’s leading documentary photographers.” (from her site)

Atwood has always used her camera as a means to tell stories too often not even dismissed but denied, and she has granted a level of dignity and consideration to those whom are too often not considered human but detritus.

A good friend is a theologian, but of the liberation theology vein: I enjoy talking with them, as their righteous anger is only matched by their ability to quote that repeatedly translated and edited text with a sense of the public good. I mention them as they once pointed out that in the New Testament, only one person was promised a place in the ‘kingdom of heaven’, and that was one of the criminals being crucified at the same time as Jesus.

In a more modern sense, I might cite Lutheran Minister (and ‘public theologian’) Nadia Bolz-Weber‘s contemporary addendum to the beatitudes, which include ‘Blessed are those who have nothing to offer. Blessed are they for whom nothing seems to be working.’

Atwood published ten books of her work and been awarded the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography, the Grand Prix Paris Match for Photojournalism, the Oskar Barnack Award, the Alfred Eisenstadt Award and the Hasselblad Foundation Grant twice.

More of Atwood’s work can be seen here.

Like several of the books I’ve recommended, this is one I came across in my local library.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

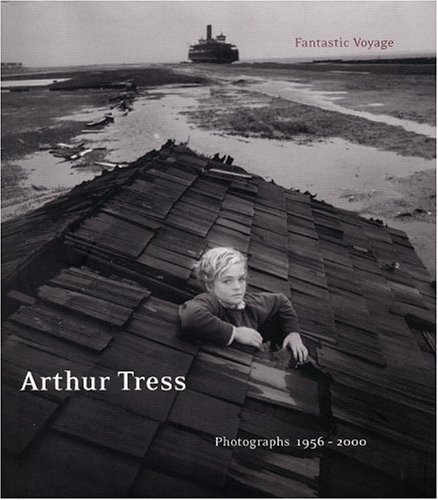

Arthur Tress: Fantastic Voyage, Photographs 1956-2000 | 2001

November 10, 2022Arthur Tress: Fantastic Voyage, Photographs 1956-2000

200 pages, Hardcover, Bulfinch, 2001.

Arthur Tress (Photographer), with writing by John Wood and Richard Lorenz

There was a recent exhibition of Tress’ photographs mounted at Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto, and that brought his work back to mind. Having enjoyed several of his books, I returned to this one – which is, for me the definitive publication of Tress’ art and aesthetic – and it’s definitely worthy of a Library Pick.

Tress’ works are striking, if unsettling. An initial amusement or facile reading gives way to a more conflicting or uncanny narrative upon closer consideration. He shares this with photographers like Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Mary Ellen Mark, Diane Arbus and – an artist featured in a previous Library Pick – Roger Ballen.

“Tress started out as an ethnographic documentarian but, partly inspired by the rituals he recorded, turned to ever more premeditated subjects. In an early project, he asked New York children to tell him their dreams and then posed them, with appropriate trappings, in neighborhood spaces to illustrate their sleeping fancies. His projects since the mid-1980s involve arrangements of tools, toys, furniture, dolls, and other stuff that Tress paints and lights to suggest scenarios and even narratives. Besides the short-term projects, Tress has made surrealist outdoor still lifes and male nudes over longer periods. The latter, including some of his best-known pictures, are implicitly homoerotic but considerably more apprehensive and even dread-filled than the nudes of fellow gay surrealist Duane Michals. But there is more humor and less darkness in Tress’ highly polished work…” (from Tress’ site, which is worth spending some time exploring, as well)

“Arthur Tress’s career can be seen as a long fantastic voyage – from early photojournalism into the realm of surrealism, eroticism and miniature worlds. This retrospective is an overview of Tress’s career. As the title implies, Tress’s work is full of fantasy – nothing is what it at first seems. His images contain dark undercurrents and light wit, violence and beauty, futuristic scenes and homoerotic and psychologically charged tableaux. The 250 images featured in this volume range from the early black-and-white work to the richly coloured surrealistic images of the 1990s and his latest, previously unpublished work in progress. Richard Lorenz, (curator of a retrospective exhibition in Washington, DC, in May 2001) offers an in-depth biographical essay on Tress and the development of his vision. An essay by noted photo critic John August Wood puts Tress in context.” (from here)

The images I’ve shared here are from the bodies of work by Tress that are my favourites – primarily Dream Collector (1970 – 74), Theater of the Mind (1976 – 77) and Still Life (1981 – 83): but there’s other series in this book that are very different, and a testimony to the breadth of his aesthetic and career. These include the starkness of his documentary work in Appalachia (1969) to the uncanny quality of his Fishtank ‘installations’ (1989) to the moribund garishness of Hospital (1985 – 87).

From the Corcoran’s review of this publication: “Tress’s work, above all else, reveals a personal approach to photography, a subjective view of the world that continually reinvents itself while it ponders universal archetypes and myths.”

Arthur Tress was a previously featured artist in AIH Studios’ ongoing Artists You Need To Know series: that can be enjoyed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

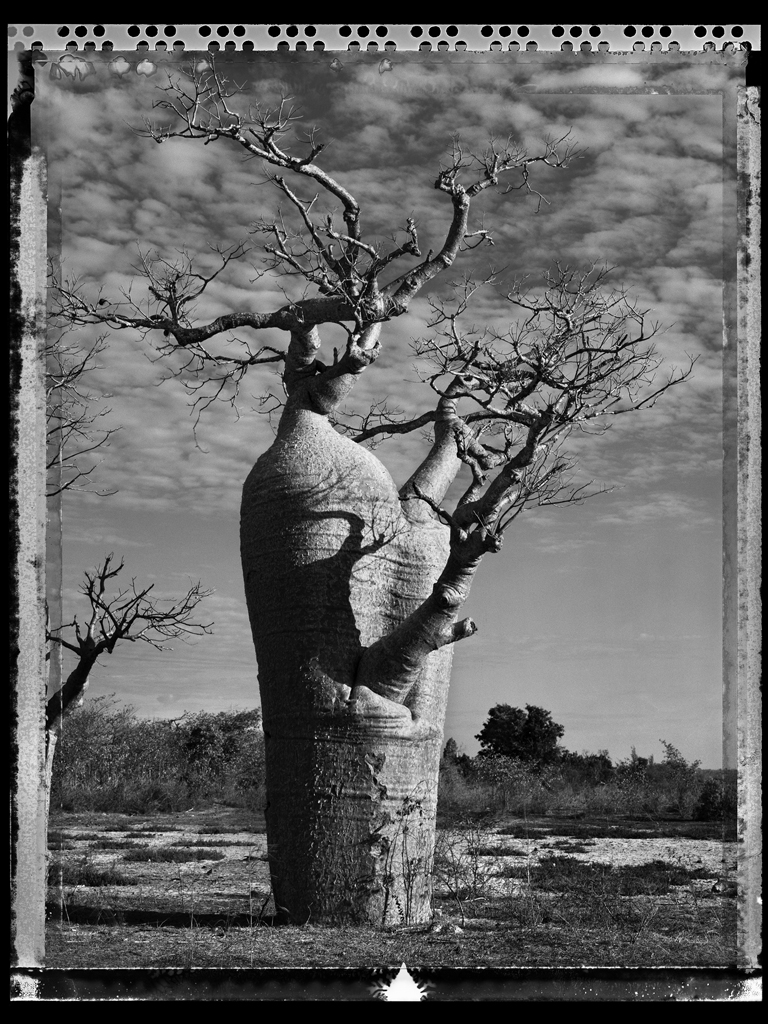

Elaine Ling | Baobab #31 – 2010, Madagascar

November 19, 2022Elaine Ling | Baobab #31 – 2010, Madagascar

Ce qui embellit le désert, dit le petit prince, c’est qu’il cache un puits quelque part…[What makes the desert beautiful, said the little prince, is that somewhere it hides a well…]

It is an odd feeling to encounter the work of an artist, seeing how prolific they are and be enamoured of their practice, then discover that they passed a few years ago. I’ve often had the same experience with authors (I have a habit of finding the work of a writer that is new to me, and consuming all the books, and it’s an empty sadness when you realize they won’t be creating any more).

This image is one from a series titled Baobob, by the late Elaine Ling (1946-2016). At her site it is the final series presented, from an extensive and enthralling body of work.

It can be read as having the quality of an epitaph: these massive, seemingly eternal natural ‘monuments’ that have survived her, and will likely survive all of us.

In that manner I have of being ‘too subjective’, Baobob trees remind me of Antoine de Saint Exupéry’s novel Le Petit Prince (1943): to me, it’s a melancholy story, about loss and death, with touching moments of truth that have contributed to how it – despite often being considered a story for children – speaks to many adults, like myself.

“Seeking the solitude of deserts and abandoned architectures of ancient cultures, Elaine Ling…explored the shifting equilibrium between nature and the man-made across four continents. Photographing in the deserts of Mongolia, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Timbuktu, Namibia, North Africa, India, South America, Australia, American Southwest; the citadels of Ethiopia, San Agustin, Persepolis, Petra, Cappadocia, Machu Picchu, Angkor Wat, Great Zimbabwe, Abu Simbel; and the Buddhist centres of Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Tibet, and Bhutan; she has captured that dialogue.” (from her site)

Voici mon secret. Il est très simple: on ne voit bien qu’avec le cœur. L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux [Here is my secret. It is very simple: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye].

On the first of August, 2016, Elain Ling lost her battle with lung cancer: her brother – Edward Pong – has indicated that he intends to continue to foster her legacy, through the maintenance of Ling’s site.

It is an impressive space with much more about Ling’s life and work – and many more of her moments from her life and around the world – that can be enjoyed here. C’est véritablement utile puisque c’est joli [It is truly useful since it is beautiful].

All quotes in italics are from Saint Exupéry’s The Little Prince .

Elaine Ling was also a recently featured Artist You Need To Know, in AIH Studios’ continuing series. You can enjoy that here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

HAUNTED | DREAMING | CITY | STEVEN LAURIE

December 30, 2022HAUNTED | DREAMING | CITY | STEVEN LAURIE HAUNTED | DREAMING | CITY | STEVEN LAURIE @_steven_laurie_ @stevenlaurie_bw Steven Laurie Photography... Read More

Julianna D’Intino | Connecting Rods: A Survey of Industry in the Niagara Region, 2015 – 2022

September 22, 2022Julianna D’Intino | Connecting Rods: A Survey of Industry in the Niagara Region, 2015 – 2022

To talk of the legacy of GM when you live in the city of St. Catharines is akin to how your tongue will always go to the gap in your teeth, seeking something that was there and now is not, leaving nothing behind but a perceptible absence you are unable to ignore.

Julianna D’Intino’s images, both moving and still – and I’ve been lucky enough to see several bodies of work she’s produced – often have a local focus, and in some ways she steps into that role of photographer as social historian. Often this involves her adjacent community in Niagara, exploring her own immediate heritage and circle. One such series can be seen here.

Connecting Rods: A Survey of Industry in the Niagara Region is a family story, as well as a local one. The ‘connection’ in the title of this series is not just a nod to an industrial interpretation, but also the families, communities and city that is part of a network that once had its epicenter in the abandoned wastelands D’Intino presents us with….and in her fine words about this series, D’Intino also draws connections to other areas with similar experience, such as with Atlas Steels or John Deere in Welland.

That potential for ‘nostalgia’ doesn’t mean what D’Intino is telling us is through rose – coloured glasses, nor does it gloss over the reality: her words about this work are as unflinching and honest – and engaging – as her photographs.

“This is but one personal case study in the myriad of lost industry of the Niagara Region. Would the return of the Niagara Region as a manufacturing hub provide a sustainable solution to the region’s economic woes? No, it would not. What is missing in the region is sufficient work at wages high enough to sustain a well-balanced life at the Niagara Region’s new inflated cost of living. The last time that such security was widespread was when manufacturing was a leading industry.”

The legacy of GM in St. Catharines is surely a contested narrative, with ground fertile for those from here – like D’Intino, or myself – to mine. It’s as rife as the industrial damage left behind at the site (an ongoing issue in civic politics here which has led to some grotesque and unsettling bedfellows), and there are differing opinions in play. Anna Szaflarski, for example, offers another perspective on this history here.

D’Intino’s site is here, and more images and D’Intino’s considered words about Connecting Rods can be found here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

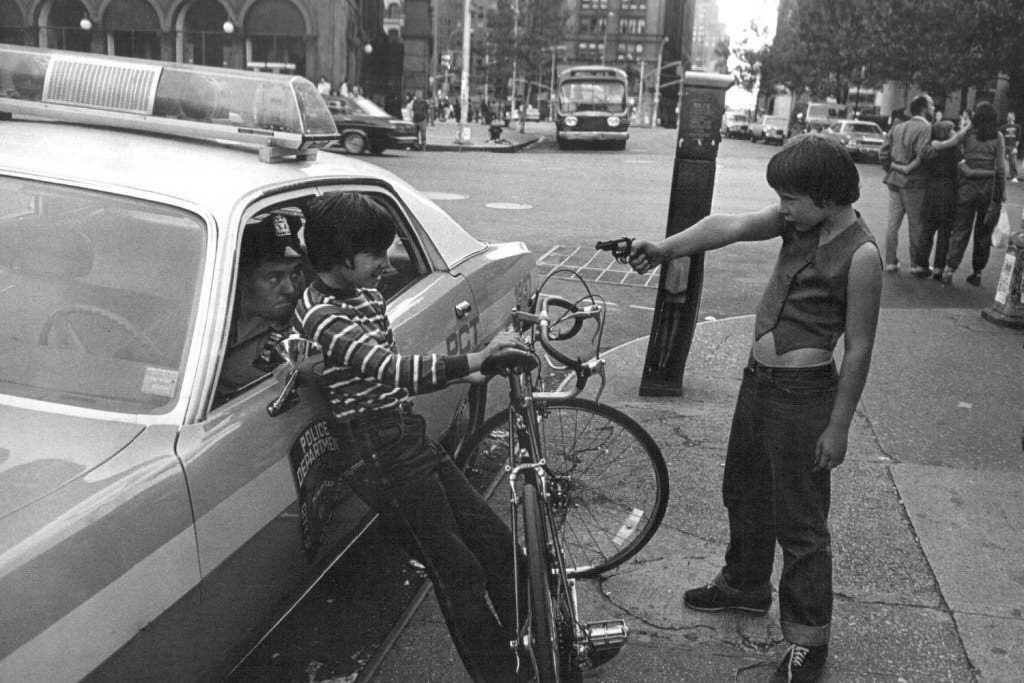

Gun Play | Jill Freedman

August 8, 2022Jill Freedman is a name you should know in the world of photography… but more than likely don’t. With a career that spanned 40 years, 7 (and counting) books and pieces acquired by major galleries, Freedman’s work connects deeply with her subjects in a manner unlike most documentary photographers.

From the very beginning, Jill was IN. She didn’t go to take photos of Resurrection City in Washington in 1968; she LIVED in the camp with the protesters for the duration of that campaign. She travelled with the circus for several months in the early 70’s to get her incredible photos of life under and around the big top. She embedded herself in the firehouses and police precincts of NYC and came out with work so beautiful and intimate that her two books on the subjects (Firehouse and Street Cops) were snapped up by first responders when they were re-released in the early 2000’s.

When Pulitzer Prize winner Studs Terkel wrote his oral history Working in 1974, Jill Freedman was who he interviewed when talking about photographers. From the first time I saw her work, I knew that there was an extreme tension in how she approached it. “Sometimes it’s hard to get started, ’cause I’m always aware of invading privacy. If there’s someone who doesn’t want me to take their picture, I don’t. When should you shoot and when shouldn’t you? I’ve gotten pictures of cops beating people. Now they didn’t want their pictures taken. (Laughs.) That’s a different thing.”[i] Freedman walked a very thin line between rooting for the underdog yet respecting authority.

You can find out more about Jill Freedman at http://www.jillfreedman.com/. Resurrection City, 1968 was recently re-published and can be found for purchase at your favorite bookstore or online. Firehouse and Street Cops are no longer in print, but used copies can be found online.

[i] Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do by Studs Terkel Text © 1972, 1974 by Studs Terkel – The New Press, New York, 2004, Pg. 153-154

~ Mark Walton

Read More

Recent Comments