In: Curators Picks

Artem Humilevskyi | Untitled from the series Giant, 2020 – 2021

January 13, 2023Artem Humilevskyi | Untitled from the series Giant, 2020 – 2021

F. once said: At sixteen I stopped fucking faces. I had occasioned the remark by expressing disgust at his latest conquest, a young hunchback he had met while touring an orphanage. F. spoke to me that day as if I were truly one of the underprivileged; or perhaps he was not speaking to me at all when he muttered: Who am I to refuse the universe? (Leonard Cohen, Beautiful Losers)

Many years ago – as in decades – I fulfilled a dream I had of being a Ramboy in the artist Evergon’s photographic series Ramboys: A Bookless Novel. These were primarily nude portraits, and though it was a wonderful experience it is somewhat intimidating to be so exposed both in the moment and with the photograph afterwards (even when young and relatively fit).

I used to joke that I hoped that no other images of myself might proliferate, so that when I was arrested for some crime, newspapers and media would need to use that image, to much amusement and potential scandal (for others, not me. I would later work with Evergon again, ‘playing’ Puck in his photographic iteration of A Midsummer Night’s Dream).

But there is always a vulnerability in self portraiture, whether you’re bare or baring an aspect of yourself. This is present not just in the creation of the work, but also in considering how those images might be received.

That courage in the face of vulnerability – real or imagined, potential or expected – is what initially engaged me about Artem Humilevskyi’s series GIANT.

“Before he released GIANT, a series of self-portraits, Artem Humilevskyi’s finger hovered over the “publish” button for six hours. It was a personal project that required him to bare all, both physically and philosophically, and he had no way of knowing how people might react. In the end, it was worth the risk. “Hitting that button was a decisive step in the project,” he says. “When I did it, I realized that nothing happened. No one threw stones at me; all the experiences I had dreaded lived only in my head.””

“GIANT is a two-year project that began in March 2020. The collection is about understanding and accepting yourself as a human being. It is not necessarily body positive or a call to change the norms or the aesthetics of the body. It is a way of denying the sexualization of the human body, it’s about accepting yourself as an individual and being able to make friends with yourself; a way to stop hating yourself for your imaginary flaws. It has not been easy because real freedom from external and internal condemnations is not possible without a fight. Each photograph is a new step on this path to this freedom. The body as a subject in the project is not important, it can be an interpretation of any of the qualities that you dislike or hate. Reconciliation with them is the only way to become a complete person who understands that all our troubles are only inside our minds. Love yourself for what you used to hate and you will feel true freedom.” (from here)

More of this series can be seen here.

IG: @humilevskiy

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Romina Ressia | Woman with a Water Pistol, 2014

January 6, 2023Romina Ressia | Woman with a Water Pistol, 2014

Most of the writing around Ressia’s photographs talks about absurdity and anachronism: perhaps that’s because she appropriates form and redefines meaning in a manner that challenges art historical tropes around gender and relevance. Meticulously executed, her ‘portraits’ have a gravitas on the one hand, but then this is broken by elements that can’t help but amuse (though her people never crack a smile, with eye contact that might wilt any irreverence from the viewer).

There is a hint of dourness to the woman who is the player in this series, and many others, having a heavy handed seriousness that is then fractured by the various objects her subjects are brandishing that seem silly and puerile.

Bluntly, Messia’s Woman with a Water Pistol looks like she’s had just about enough of you, young man, and unless you want to be sprayed with water – disciplined like an unruly, disobedient cat – you’d best behave. You shan’t be told again.

A bit flippant perhaps. But consider the [still, uninterrupted] proliferated misogyny in Western art history [or contemporary art] of women as object, or demure commodity, or the validation / apologia of rape as seen with Europa or the Sabine women or ‘Susannah and the Elders’ (and so, so many others). Consider that in (recently done) 2022 we’ve seen groups of women around the world make it clear that they have had *quite* enough and my interpretation is not without consideration….

This image is part of a larger series titled How would have been Childhood? with the same figure in them all, her unimpressed body language acting as a unifying aspect of the artworks. Birthday hats, costumes, balloons – nothing seems to inspire joy, here. When I first encountered this series online, a birthday party that no one was enjoying – if anyone even came, besides the ‘star’ of the series – can be forgiven for being an initial impression….

“Romina’s art cleverly initiates dialogue on important contemporary social issues through the striking use of anachronistic tropes juxtaposed with mundane and banal elements of modernity. Indeed, the influence of classical artists like Da Vinci, Rembrandt and Velazquez is instantly recognizable in the palettes, textures, ambiance and scenes captured in Romina Ressia’s works, bequeathing them an air of familiarity which only serves to highlight the contradictory and sometimes confrontational presence of objects of modernity such as cotton candy, bubble gum, microwave popcorn and Coca Cola.

The theatrical absurdity in her pictorial compositions, which combine stylistic elements of Renaissance paintings and Pop art, and the dissonance of the stark contradictions captured therein have a surprising clarity, making for an honest critique through visual dialogue of received notions of modernity. In this sense, Romina succeeds in achieving her artistic intent which is not to recreate or refer to the past but to establish a frame within which to interrogate the perceived evolution and progress of society especially in respect to the role and identity of women.” (from here)

If you’re doltish enough to suggest ‘she’d look better if she smiled’, don’t be surprised if you get soaked – deservingly.

More of Romina Ressia’s evocative – if a bit disquieting – work can be seen here.

Her Instagram is @rominaressia

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Nadav Kander | Chernobyl, Half Life, 2004

December 23, 2022Nadav Kander | Chernobyl, Half Life, 2004

I drink to our ruined house,

to the dolor of my life,

to our loneliness together;

and to you I raise my glass,

to lying lips that have betrayed us,

to dead-cold, pitiless eyes,

and to the hard realities:

that the world is brutal and coarse,

that God in fact has not saved us.

(Anna Akhmatova, I drink to our ruined house…, 1934)

I am old enough to remember when Chernobyl happened, and like many events it has become larger in the public consciousness as the years pass. In some ways, my time as a teenager had numerous events that have shaped history, as I also remember being in my high school history class and discussing the fall of the Berlin Wall, which happened a few years later.

One can’t speak of the fall of the Soviet empire without citing Chernobyl: Emmanuel LePage, in the graphic novel Springtime in Chernobyl (2012), asserts that ‘the disaster in Chernobyl is the first nail in the coffin of the Soviet Bloc.’ It is not unintentional, I think, that this metaphor is employed after an earlier passage where a widow describes the elaborate entombment of her husband’s irradiated body, like a pharaoh’s sarcophagus to hell instead of heaven…

It has become a touchstone for many artists in a variety of mediums. Some use this disaster as a means to a larger conversation. Others remind us of Stephen King’s Blind Wille reminiscing about his time in Vietnam (from Hearts in Atlantis), admitting it had much to “teach him, back in the years before it became a political joke and a crutch for hack filmwriters.”

In writing about his series Chernobyl, Half Life (2004), Nadav Kander offers the following:

“Reactor No.4 at Chernobyl’s Nuclear Power Station exploded in 1986 leaving the surrounding area uninhabitable for many hundreds of years to come. It happened to be the 20th Anniversary since the explosion when I gained access as an artist to visit Chernobyl, photographing the deserted spaces in what was once a model Soviet City.

Home to more than 40,000 people, the apartments, schools and hospitals that were hastily left following the controversial evacuation are stark reminders of past lives, leaving a disturbing sense of quiet. An uneasiness that I had never previously experienced.

There is a great beauty in a very real way to be found as the poignancy of human suffering almost hangs in the air. I found myself with a familiar feeling; best described as the feeling when walking through an overgrown cemetery on a drizzly day, but what I was looking at was far from familiar.

Having grown up with stories of relations of mine including my Father with his family that were suddenly evacuated during the second world war, I could not help but feel quite profoundly shocked as well and at the same time wonder what it must have felt like to suddenly leave your home and be transported to an unknown destination, suspecting that the near future would probably bring severe ill health due to being exposed to large doses of radiation. Little is known about the radio-active affects on the people of this city as the population were dispersed all over Russia. If there was a gathering of data by the government, it was never reported.”

I’ve selected a few of the images from this series, and most of them are focused upon spaces that would be set aside for children. Kindergarten Golden Key, Sleeping Room evokes a memory of visiting Spring Hurlbutt’s The Garden of Sleep / Le Jardin du Sommeil, which was also a contrasting beautiful space to meditate upon the death and loss of children, and both provide a focus for grief.

With work like this, there is a danger of the glorification of destruction: what one of my critical brethren has called ‘ruin porn.’ Kander, however, with his choice of sites has privileged the people – their absences are very clear, in the scenes he depicts – so that amidst all of the geo political discourse, humans and our humanity is not forgotten, willfully or otherwise….

Akhmatova’s words from half a century earlier act as a fine narration of these images: as an addendum to this pick, I’d also suggest the series Chernobyl, as it also focused upon the reality of Pripyat residents, situated within a larger historical narrative (much like Ahkamatova’s poems do).

And, with Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine, some historians are reminding us of past events like the Holodomor – and in some ways, Chernobyl fits within this – where an ’empire’ exhibits cruelty and disregards humanity, whether through malevolence or ignorance, and sometimes I see Chernobyl through this lens, as well….

There is a surfeit of cultural commemoration or interpretation of this event and some is better than others. Kander’s work is quietly unsettling, even after all these decades.

More of this series can be seen here.

IG: @nadavkander

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Dan Kennedy / Dr. Erosion | Animations, 2019 – 2022

December 15, 2022Dan Kennedy / Dr. Erosion | Animations, 2019 – 2022

I’ve always been a fan of animation in its many forms (I am a member of Gen X, so Saturday morning cartoons shaped me, but I also remember watching Science Ninja Team Gatchaman – and the butchered Western version Battle of the Planets when small, and Akira [アキラ] is another seminal experience, for me, when young).

Speaking as a more mature viewer, The Brothers Quay’s Street of Crocodiles (1986) is something I can watch over and over: and recently I rediscovered the 1986 animation The Mysterious Stranger, from the larger film The Adventures of Mark Twain (that vignette is based on Twain’s ominous story of the same name). The shifting mask of Satan, in that claymation, disturbed me as a child and still horrifies me now. Perhaps, with stop action animation, there’s that same ‘perversion’ of the human body that we see in work with dolls, as I touched upon when responding to Gabrielle de Montmollin’s Weird Baby World installation.

When I began researching Dan Kenndy / Dr. Erosion’s work, I was mostly familiar with his two dimensional ‘still’ artworks, but soon became engrossed with his short ‘films’. Drawing Time, Cats Dream of Water, Where is the Blue Fairy? – and many others – are brief visual anecdotes, amusing and disturbing simultaneously.

The images below are teasers for the longer works, which can be enjoyed here (works from 2019) and here (works from 2020 – 2022).

Kennedy’s aesthetic is ghostly ethereal and densely complicated, pulling upon his continuing “explorations of commercial culture or as he refers to it, ‘the commercial unconscious”.” (from here) There are hints of Hieronymous Bosch in these brief vignettes from Dr. Erosion / Kennedy that are engaging but also eerie.

When I’ve written about abstract painting I’ve often stolen and shared an idea from art historian Julian Bell: ‘In other words there was no prior context to the painting itself. The viewer’s eyes would submit, and the painting would act.’ Kennedy’s works are often short, and this makes them even more focused – like a sharp taste, where more would be too much.

Dan Kennedy / Dr. Erosion was also a previously featured Artist You Need To Know in AIH Studios’ continuing series. That can be explored here.

IG: @dr.erosion

https://www.dankennedy.ca/

More animated works from Kennedy / Dr. Erosion can be found on VIMEO.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Elena Chernyshova | Days of Night / Nights of Day, 2012-2013

December 8, 2022Elena Chernyshova | Days of Night / Nights of Day, 2012-2013

‘I was with my people then, there, where my people, unfortunately, were.’

(Anna Akhmatova, Requiem, 1935 – 1961, writing of her times in the soviet gulag)

When I lived in Saskatoon, an acquaintance who’d spent time in Eastern Europe once commented that that city in winter was like Siberia, but without the cachet of being that place (which exists as much in our imaginations as it does in reality, one might say – as a ‘great part of the imagination of the world is attached to that site’), nor with architecture that was anything but a failed brutalism (this was during a period with the ‘economic boom’ in Saskatoon where a number of heritage buildings were lost and the banal taupe of others rose like mottled angular tumours….)

Elena Chernyshova’s work is aesthetically stunning: not just for the evocative quality of the images, but also for the scenes they present to us, that seem to blend exotica and danger, a chronicle of sites that remind us of the irrelevance of humanity in the face of nature.

But her notes and comments bring the human element back, as this is not just a ‘pretty’ image, but a site of – of course – contested narratives, that looks back to the history of the USSR and some of the ideas of industrialization and ‘progress’ that have human costs.

Chernyshova’s own words are a powerful adjunct to her lens: “Days of Night / Nights of Day is about the daily life of the inhabitants of Norilsk. Norilsk is a mining city, with a population of more than 170,000. It is the northernmost city (100,000+ people) in the world. The average temperature is -10° C and reaches lows of -55° C in the winter. For two months of the year, the city is plunged into polar night when there are zero hours of sunlight.

The entire city, its mines and its metallurgical factories were constructed by prisoners of the nearby gulag, Norillag, in the 1920s and 30s. 60% of the present population is involved with the city’s industrial processes: mining, smelting, metallurgy and so on. The city sits on the world’s largest deposit of nickel-copper-palladium. Nearly half of the world’s palladium is mined in Norilsk. Accordingly, Norilsk is the 7th most polluted city in the world.

This documentary project aims to investigate human adaptation to extreme climate, environmental disaster and isolation. The living conditions of the people of Norilsk are unique, making them an incomparable subject for such a study.”

Chernyshova offers the following about the image of monumental architecture (with a blue suffusing light): The construction plan of Norilsk was established in 1940, by architects imprisoned in the nearby Gulag. The idea was to create an ideal city. The most “ancient” buildings are constructed in the Stalinist style. The next step of construction happened in the 60s, when the prevailing method in the USSR was to use pre-built panels.

Her other writings also allude to the disputed, if not adversarial, stories that meet and intersect in Days of Night / Nights of Day. The scene with the car and hazy clouds the colour of sulfur has the following notation: In the summer, there is a period when the sun doesn’t go under the horizon. This continues from the end of May till the end of July. It is accompanied by good weather and pleasant temperatures. Around 3 am, while the city sleeps, it is still illuminated by the sun. The city seems like a ghost town, emptied of its inhabitants.

One of the images I’ve included from Chernyshova’s series is unlike the others: and its difference helps to offer insight into the whole. Again, Chernyshova’s voice must be borrowed: Anna Vasilievna Bigus, 88, [who] spent ten years of her youth in the Gulag. At age 19, she was separated from her family and sent into the Arctic Circle. “The only joy we could have in Gulag was singing. We sang a lot. And this gave us the strength to survive…” Her daughter became a music teacher and her grandchildren sing in opera.

The complete series (produced with the support of The Jean-Luc Lagardère Foundation) can be seen here and a feature from LensCulture (where Chernyshova offers some words about many of the images I’ve shared here, that offer more nuance and depth to her vision) can be enjoyed here.

Elena Chernyshova’s site

@elena.chernyshova.photography

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Haruko Maeda | Self – Portrait with my cat and my grandmother in a glass, 2020

December 2, 2022Haruko Maeda | Self – Portrait with my cat and my grandmother in a glass, 2020

Several years ago, when I was going through the library of a recently deceased friend – at the invitation of his daughter – I noticed in his (former) apartment that she had a velvety bag, looking lustrous and fancy. I asked if this was some expensive alcohol, to mark her father’s passing. She told me it was her father’s ashes. When I asked if they’d be scattered in the city we were in, as he’d lived there for some time, contributing to the critical writing community and being a significant voice around visual culture and especially photography, or back in his home province in the Maritimes, she tersely commented she had not decided yet whether they’d be flushed down the toilet or mixed in with the cat litter.

When my own father passed several years ago, not long before COVID, the arrangements around his inurnment were put on hold: his ashes sat on a shelf in the living room of what is now my mother’s house for some time, only recently being put underground this past summer. Frankly, having ‘him’ in the same room where he spent most of the final years of his life seemed to comfort my mother: he was more agreeable than he’d been in decades, ahem.

No, I am not smiling – my face is as stoic and unreadable as Maeda’s, in her painting.

Those are both dark places to begin in considering Haruko Maeda’s painting Self – Portrait with my cat and my grandmother in a glass: but the funerary rites and rituals of family are nothing if not contested narratives that bring feelings to the surface, re opening old wounds and making new ones. Leave the dead to bury the dead, they (Matthew and Luke, to be specific, but that may just be hyperbole) say, but they never truly ‘leave’ us….

Maeda looks unperturbed in this scene: her cat seems relaxed, and even the fly that perches upon her arm that holds the ashes of her grandmother is subtle.

“Japanese Haruko Maeda lives and works in Austria since 2005. In her art she combines the Shintoistic traditions of her homeland with the Roman Catholic faith, deeply rooted in Austrian culture and history. This allows her to position herself between East and West. Maeda lets these double belongings function as a kind of filter through which she can process her own memories and experiences. The purpose is to raise universal questions about existence, life and death.” (from here)

In Neil Gaiman’s Sandman series, the final story arc – The Wake – offers several vignettes as concluding narratives about death, loss and mourning. One of these involves a man cast into exile, after the death of his son, who gets lost in a desert that his guides will not name, as to do so is to invite disaster. Master Li finds a tiny kitten as a companion, a ward, perhaps, against the ghosts of the dead he encounters in the ashy, shifting sands. At some point he encounters the shade of his son, and this is their conversation:

“Father? I am your son. That is only a kitten. Why do you abandon me to chase after it?”

“When you were alive, you were all my joy. Now you are dead. I see you only in my dreams. And when I awake my pillow is wet with tears. The kitten is living, and it needs my help.”

There is a solemnity to Maeda’s work, but also just a touch of irreverence.

More of Haruko Maeda’s work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

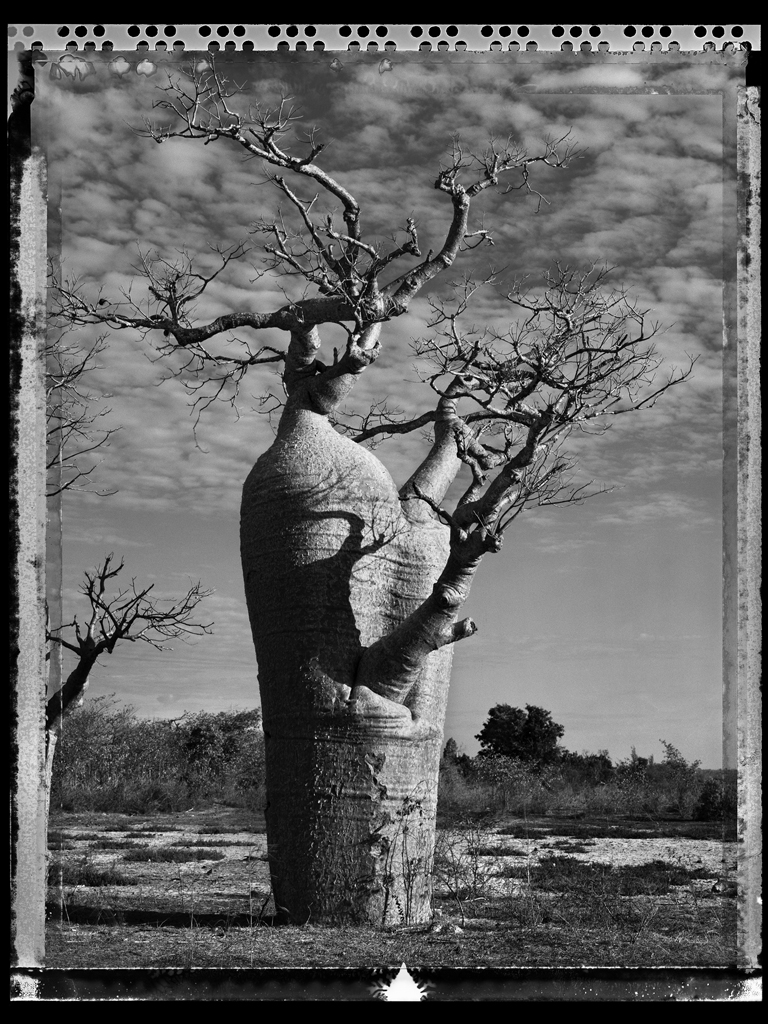

Elaine Ling | Baobab #31 – 2010, Madagascar

November 19, 2022Elaine Ling | Baobab #31 – 2010, Madagascar

Ce qui embellit le désert, dit le petit prince, c’est qu’il cache un puits quelque part…[What makes the desert beautiful, said the little prince, is that somewhere it hides a well…]

It is an odd feeling to encounter the work of an artist, seeing how prolific they are and be enamoured of their practice, then discover that they passed a few years ago. I’ve often had the same experience with authors (I have a habit of finding the work of a writer that is new to me, and consuming all the books, and it’s an empty sadness when you realize they won’t be creating any more).

This image is one from a series titled Baobob, by the late Elaine Ling (1946-2016). At her site it is the final series presented, from an extensive and enthralling body of work.

It can be read as having the quality of an epitaph: these massive, seemingly eternal natural ‘monuments’ that have survived her, and will likely survive all of us.

In that manner I have of being ‘too subjective’, Baobob trees remind me of Antoine de Saint Exupéry’s novel Le Petit Prince (1943): to me, it’s a melancholy story, about loss and death, with touching moments of truth that have contributed to how it – despite often being considered a story for children – speaks to many adults, like myself.

“Seeking the solitude of deserts and abandoned architectures of ancient cultures, Elaine Ling…explored the shifting equilibrium between nature and the man-made across four continents. Photographing in the deserts of Mongolia, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Timbuktu, Namibia, North Africa, India, South America, Australia, American Southwest; the citadels of Ethiopia, San Agustin, Persepolis, Petra, Cappadocia, Machu Picchu, Angkor Wat, Great Zimbabwe, Abu Simbel; and the Buddhist centres of Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, Tibet, and Bhutan; she has captured that dialogue.” (from her site)

Voici mon secret. Il est très simple: on ne voit bien qu’avec le cœur. L’essentiel est invisible pour les yeux [Here is my secret. It is very simple: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye].

On the first of August, 2016, Elain Ling lost her battle with lung cancer: her brother – Edward Pong – has indicated that he intends to continue to foster her legacy, through the maintenance of Ling’s site.

It is an impressive space with much more about Ling’s life and work – and many more of her moments from her life and around the world – that can be enjoyed here. C’est véritablement utile puisque c’est joli [It is truly useful since it is beautiful].

All quotes in italics are from Saint Exupéry’s The Little Prince .

Elaine Ling was also a recently featured Artist You Need To Know, in AIH Studios’ continuing series. You can enjoy that here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Eleanor Antin | 100 Boots, 1971-73

October 28, 2022Eleanor Antin | 100 Boots, 1971-73

“For month after month after month, her five-score empty rubber boots had to be carted across the country, set up in various evocative spots, and then photographed before someone could come along and chase Antin away…at the time, the empty boots would have had immediate resonance as a reference to the Vietnam War, and to the boot-wearers who would never come home.” (Blake Gopnik)

Eleanor Antin is an artist who has not, in my opinion, received the credit she merits for her performative installations and photographs that have a cinematic quality. At the risk of being flippant, if Gopnik, Camille Paglia and I myself all agree as to her importance, we surely can’t be wrong. Antin has been making work since the 1960s, and her art often intersects with politics in both overt and covert ways.

From Paglia’s Glittering Images: A Journey through Art from Egypt to Star Wars: ‘As a work of Conceptual art, 100 Boots consisted of temporary on-site sculptural installations documented by photographs (taken by Philip Steinmetz), which were sent uninvited to a distant, dispersed audience. The formal, squadron-like patterns assumed by the boots parody the frigid geometries then being made by male Minimalist sculptors. In their outdoor placement, the boots evoke traditional landscape painting as well as the new genre of land art, which was just emerging from Minimalism. Antin strategically varied the look of the cards so that “seductively beautiful” images were not the rule. Most of them have a bleak desolation reminiscent of existential European art films. Indeed, Antin saw the work as “a movie composed of still photos”.’

Over her career, Antin ‘has utilized a staggering range of styles, media, and materials, and her work has combined theater, dance, literature, drawing, painting, sculpture, crafts, photography, video, and architecture. “All artworks are conceptual machines,” she said. And again: “All art exists in the mind.” Antin deeply influenced the emergence of both performance art and Conceptual photography.’

For myself, these images are about the insidious nature of loss, especially as it pertains to those who have died during the pandemic. Empty boots that take on the nature of ghosts that appear in any place at any time, a simple – almost banal, like a rubber boot – fact of absence that hits you like a hammer to the chest and requires you to sit down to consider it….

Eleanor Antin was a previously featured Artist You Need To Know, in AIH Studios’ continuing series. That can be enjoyed here.

More works from this series can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

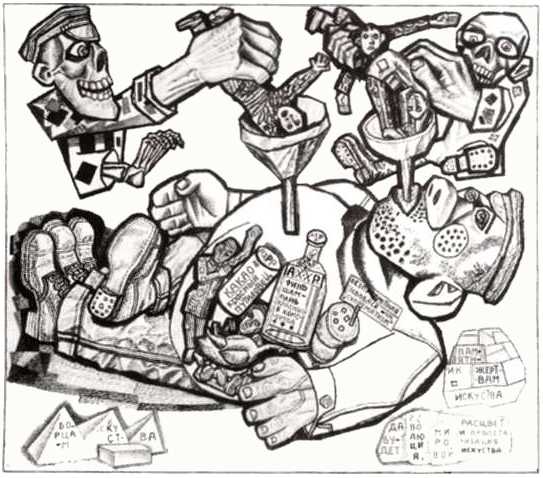

Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

October 21, 2022Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

He was walking about with a noose round his neck and didn’t know. So I told him what I’d heard about his poems.

. . . . . . . .

Yevgraf: This is a new edition of the Lara poems.

Engineer: Yes, I know. We admire your brother very much.

Yevgraf: Yes, everybody seems to.. now.

Engineer: Well, we couldn’t admire him when we weren’t allowed to read him…

Yevgraf: …No.

(both quotes from Boris Pasternak’s tale of Russia before and after the Russian Revolution Dr. Zhivago)

A defining book in my reading and understanding of art history in the 20th century is Boris Groys’ The Total Art of Stalinism: begun when the USSR was still in existence, Groys was able, with the fall of that empire, to access more information, and offer a more nuanced take upon the years post Russian Revolution, as it pertains to the arts in that rare and unique historical moment. Amusingly, I became aware of it after participating in a panel about modernism, and horrifying my fellow speakers by stating that it had failed, horribly, but that its relevance was in its ideals…

Several points stay with me, in considering Pavel Filonov’s work. One is that, in a correlation to the backward economic state of Russia making it fertile ground for a radical new approach and the subsequent revolution, the artistic milieu also suffered from this. It’s not incidental that so many significant artists – not just to Russia but to ‘western’ art history – like Malevich or the Suprematists flourished during the first heady days of the NEP. Experimentation and a sentiment that ‘anything was possible’ was pervasive and defining, with a desire to irrevocably fracture from the ‘old.’

This, of course, all ended badly, and the promised freedoms – whether artistic or personal – were soon not just reigned in, but suppressed, and a cultural exodus from the USSR to other places was predictable.

Filonov (1883 – 1941) served in WWI and would die of starvation during the siege of Leningrad, the once and present St. Petersburg, in the war that followed the ‘war to end all wars.’

The painter, art theorist and poet was an outsider, even during the pre and immediately post revolutionary days of promise: after several failures, in “1908 Filonov was admitted at last to the Academy of Arts. His works attracted the attention of both students and professors by their unusualness: they were not abstract and depicted their subject with full likeness, but were executed in garish, bright colors – reds, blues, greens and oranges. This manner did not conform to the Academy standards, and Filonov was dismissed “for influencing students with the lewdness of his work”. Filonov protested the decision of the rector Beklemishev, and was rehabilitated, but after studying for two years he left the Academy in 1910.”

He was one of many whose works were deemed degenerate, as they eschewed official socialist realist policy. He’d be lost to us, in terms of history, but for the efforts of his sister Yevdokiya Nikolayevna Glebova: “She stored the paintings in the Russian Museum’s archives and eventually donated them as a gift. Exhibitions of Filonov’s work were forbidden. In 1967, an exhibition of Filonov’s works in Novosibirsk was permitted. In 1988, his work was allowed in the Russian Museum. In 1989 and 1990, the first international exhibition of Filonov’s work was held in Paris.

During the period of half-legal status of Filonov’s works it was seemingly easy to steal them; however, there was a legend that Filonov’s ghost protected his art and anybody trying to steal his paintings or to smuggle them abroad would soon die, become paralyzed, or have a similar misfortune.”

It’s unsurprising that Filonov was deeply influence by fellow dissident Klebnikov: and his works – whether the obvious disdain present in this piece The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, or the more stark Those Who Have Nothing To Lose, or Animals, that would make a fine illustration for Orwell’s Animal Farm decades later – have an unflinching quality.

More of Filinov’s life and legacy can be learned here (and was the source cited for the biographical quotes about his life and work).

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Asya Kozina | Baroque Paper Wigs, 2016

October 14, 2022Asya Kozina | Baroque Paper Wigs, 2016

Historical wigs always fascinated me, especially the Baroque era. This is art for art’s sake aesthetics for aesthetics, no practical sense. But they are beautiful. I made a series of wigs. Paper helps to highlight in this case the main form and not be obsessed [with] unnecessary details.

There is something both decadent and timeless about Kozina’s work. The idea of a peformative lens comes into play – as these intricate, hand made (with no digital tools) ‘wigs’ only attain their ultimate beauty when worn by one of Kozina’s models, and the rest of the team comes together (meshing together, perhaps, like the paper in the artist’s constructions) to produce a moment that has as much to do with art historical tropes, as seen in the paintings of Jacques Louis David or Caravaggio, as it does with contemporary couture and fashion. The artifice of the apple, the pale face perfectly dotted with subtle spots of rouge, the winsome look eschewing eye contact in one scene and the feigned precociousness of the model looking directly at us in another all suggest this might be a Jean-Honoré Fragonard (more late Baroque, with a touch of the playfulness of Rococo) except for the stark palette, only broken by the red of the apple.

I think of Fragonard as the old Russian Imperial court often looked to France for its ideal, and there’s a sentiment of the elaborate, exotic Ancien Régime to Kozina’s many works: another act of imitation from an artifice of pretension that was, of course, all about social class and cultural capital.

But Kozina does more than just mimic: several bodies of work – such as the more ballistic Baroque Punk or more erotic Eve – employ the history of fashion as a starting point for contemporary considerations and conversations.

More of her work can be seen on IG at @asya_kozina or at her site.

The photographer for this work is Anastasia Andreeva, with assistance from Dina Kharitonova. The makeup artists are Marina Sysolyatina and Svetlana Dedushkina.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments