In: women

Rita Godlevskis

June 10, 2020PhotoED Magazine’s Editor /Publisher Rita Godlevskis has more than twenty years of experience in photography based, creative media work, in Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand. She has worked across multiple platforms with a diverse range of projects in her portfolio in editorial, and creative production contexts. A passion for promoting diverse voices in Canadian photography, and great coffee keep her fueled.

Read More

Peppa Martin

October 27, 2020Peppa is a gallerist, curator, art advisor and artist consultant, reviewer, career professional photographer, and independent writer on art and culture.

Read More

Paulette Cameron

November 23, 2021Paulette (she/her) is Co-Editor-in-Chief and Creative Director of Like A Prayer Magazine. A recent graduate of a Master’s in Architecture from Dalhousie University, she is working as an Junior Architect at MacKay-Lyons Sweetapple Architects in Kjipuktuk-Halifax, Nova Scotia. Paulette’s graduate thesis – entitled Invoking Memory: Traced Narratives of Mabou, Cape Breton – focused on framing and reframing memory in a landscape-driven process. Her work teases the boundaries between art and architecture, demanding a critique of theory and process. Among her body of work, she has exhibited Newfoundland/Lines, featured in the Rossetti/Watson Exhibition; Suitcase as part of the Public Architecture Copenhagen Studio’s open exhibition; and Fabrics of Power: Past and Future presented in the Amsterdam Urban Systems Studio. She was also a contributor to Catherine Venart’s Conceiving the Plan: Nuance and Intimacy in the Construction of Civic Space exhibited in honour of Diane Lewis at the 2021 Venice Biennale. Paulette brings a nuanced design lens to the team at Covert Art Collective where she seeks a deeper understanding of process through the persons and rituals that construct it. She also currently co-hosts a radio show on CKDU 88.1 FM with her sister, Josefa.

likeaprayermagazine.com | @paulette.anne

Read More

Josefa Cameron

November 23, 2021Josefa (she/her) is a journalist and creative writer based in Halifax. She is currently working as a documentary writer with a Halifax-based production company. In 2020, she launched Like A Prayer Magazine with her sister, Paulette, and is the magazine’s Co-Editor-in-Chief/Executive Editor. Josefa is a member of the Canadian Association of Journalists and was recently named an influential woman on the East Coast of Canada by Amplify East.

Josefa studied Cultural Anthropology at The University of British Columbia and English Literature at Dalhousie University. She is currently a postgraduate student at The University of King’s College Journalism School. Josefa freelanced for The Coast, Discorder, Halifax Magazine, The Dalhousie Gazette, The Maritime Edit, ION Magazine, DOTE Magazine, Beatroute, and Weird Canada. She worked as a reporter and columnist at The Inverness Oran and a news broadcaster and interview producer at Seaside Radio. She hosted a radio show at CiTR 101.9 FM in Vancouver and currently co-hosts a radio show on CKDU 88.1 FM with her sister, Paulette.

likeaprayermagazine.com | @josefa.bambam

Read More

Rita Godlevskis – Spotlight

November 12, 2021× × Your browser does not support the video tag. Read More

Suzanne Luke

June 3, 2021Suzanne Luke is actively involved in the cultural section and has nurtured a solid reputation as an arts advocate and community leader.

Read More

Tangible Stories | Leslie Love exhibition at The Old School House

September 27, 2023Tangible Stories | Leslie Love exhibition at The Old School House

I run a medium sized arts institution in a century old building, in the oldest postal code in Canada, in a sleepy town with one set of stoplights, where Leslie Weigand Love presents Tangible Stories, an exhibition that alchemizes grief.

With such a direct and forthright conversation about life, and all the characters that weave in and out of the artists narrative, Tangible Stories bring us a capacity to understand how we can move grief : that cheese-grater heart feeling – the learning of a self anew without that physical presence of one who has passed, by drawing close the echoes of community and intergenerationality. A show created in conjunction with her deceased father, Love shows us a knowing of proximity that moves beyond death while honouring mystical answers, and the work is a multilayer practice in salvaging of family objects, repositioning how we examine daily work, and reclaiming it with a fresh contemporary take on materiality.

The repeated sunflower theme throughout the exhibition, the artist’s sunny disposition, the acknowledgement that life is a circle with petals, not a half moon horizon. A full cycle of raising children as we are raising ourselves, and with the knowledge of family and what came before, using discarded old signs silkscreened by an uncle, as substrate for paintings based on her late fathers photographs.

Ripped up mechanical manuals become petals, paint made with metal fittings from his welding shop, a repurposed welding visor that contains images of his band, an inner/outer life many artists and creatives straddle. The work we do from our hearts welded to the work we do for a paycheck to feed and provide and clothe those we love.

Remnants of her family’s work jeans ripped and braided into a rug. The mythologies we ascribe to as families as we create from our familiar collective memory – what/how we remember as small eyes, looking up to characters and personalities our parents know. A troubled band mate asleep in the coat room after a big party, the first day of moving into a new home that directly echoes the age of Love’s child when she moved back to the property she grew up on- the exhibition unfolds in thematic ripples.

Gifting the viewer with a unique and familiar feeling, how perspective shifts with time and age and the acknowledgment of vulnerability, how the back of a van was used for childhood camping but also was housing a dream of touring with a band, imagery of her parents eyes directly across from a mirror that reflects the viewers own.

I suppose it all comes back to Love, how aptly named, to bring forth so much compassion of self, honour an alchemy of grief, to show us that we can process loss in the context of community and family. That the work of materiality and re-purposing vitality, allows objects to incarnate new meaning and purpose in a cohesive beautiful exhibition of work.

This exhibition runs until October 28th, 2023, and is viewable at The Old School House Arts Center, on the unceeded territories of the Qualicum First Nations.

https://www.theoldschoolhouse.org/2023-leslie-love

~ by Guest Curator Illana Hester

Annie Collinge | Table For One | 2020

August 25, 2023Annie Collinge | Table For One | 2020

With styling and art direction by James Theseus Buck and Luke Brooks of Rottingdean Bazaar, the Table For One series was created for Luncheon Magazine, featuring the model Tin Gao.

There are a number of places to stand (or crouch, on your knees with your head tucked under, like the resting chicken ‘downward dog’ work by Collinge) in considering Table For One.

Some are more light-hearted (when I first encountered Collinge’s performative scenes, I was having the type of day where staying at home in a banana bag or sitting stoically as a snug, solitary tomato was a comforting concept. Table For One might mean being grateful to be left alone, that day). Other responses may be darker : perhaps these are incongruously bright, vibrant metaphors for loneliness and separation. Eating alone at a table for one is interpolated as isolation – and assumed to be by reluctance not preference – which feeds (sorry) into the history of how eating with others and communal meals are lauded as linchpins of social structure. This is – of course – debatable, as it has a rank stench of nostalgia, like those who lament the myth of ‘family dinner.’

I offer this as someone who often goes to movies alone, or eats in restaurants alone, but have been told I’m ‘extroverted’ in other social interactions.

When considering art, I often cite what Jeanne Randolph describes as the ‘amenable object’ : it’s a ‘vessel’ that we pour our own experiences into, and thus construct its meaning in collaboration with the artist. Fashion falls within this, and is also a manifestation of art and social history : its a history we wear and perform. As with art history, it is sometimes subversive, sometimes explicit. Table For One exists within that space.

“Puppetry, dolls and larger-than-life costumes populate the images of London-based photographer Annie Collinge. Visual trickery abounds, as if Alice had just stumbled upon a magic potion in Wonderland, with scale (the very large and the very small) frequently distorted. The human body becomes a foil to its surroundings, offsetting imaginative surroundings that conjure the escapist storybooks of childhood. A head appears amidst a mushroom patch, or else a gloved hand clutches at a disembodied head. Like the best fairytales, these images carry as much menace as they do whimsy.” That quote is from an interview with Collinge : more of that conversation can be read here.

More of Collinge’s artwork (sometimes collaborative, sometimes solo) can be seen here and here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

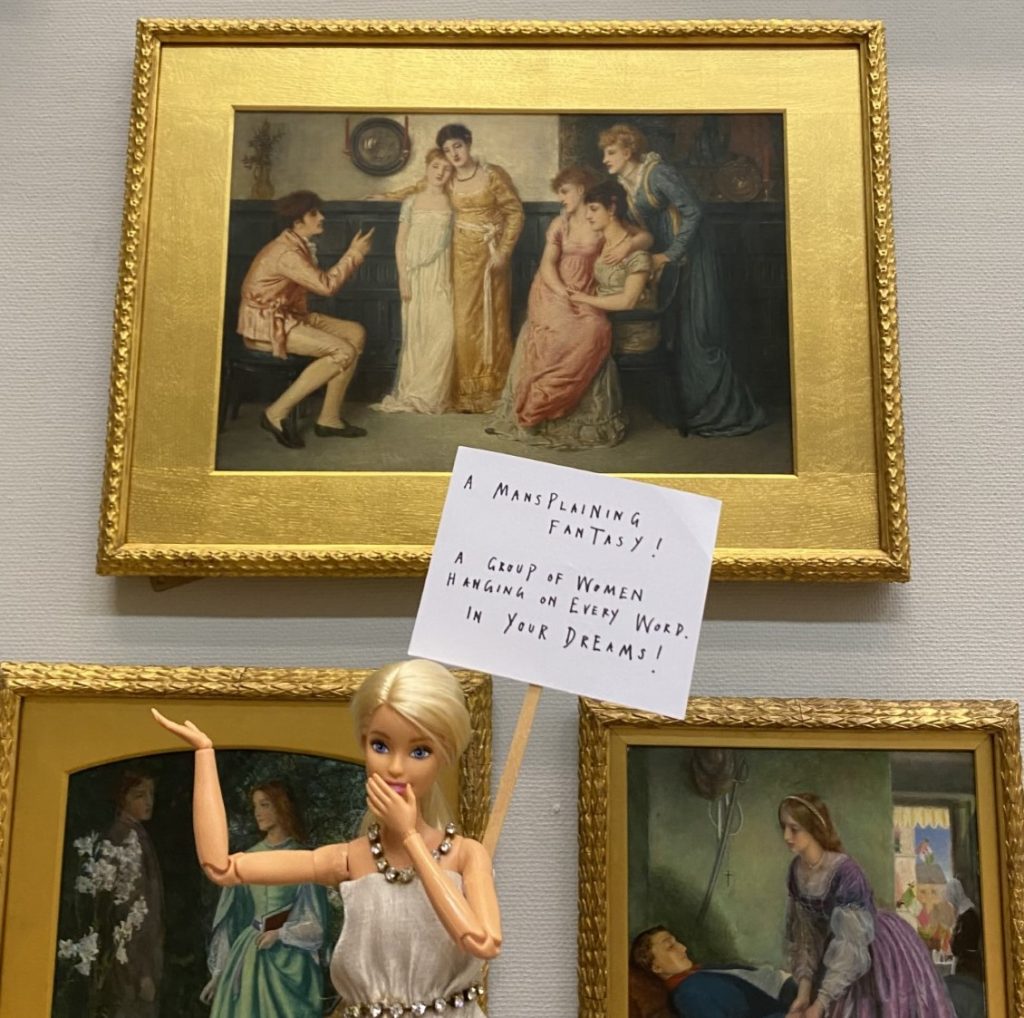

ArtActivistBarbie | Dr Sarah Williamson

August 11, 2023ArtActivistBarbie | Dr Sarah Williamson

Many years ago, when I was still working in art galleries, I was intimately involved with the first full ‘inventory’ of the Kenderdine Gallery’s art collection (now the College Gallery, at the University of Saskatchewan). This task involved documentation both visual and written, from shooting slides (yes, I am that old) and creating or augmenting artist and artwork files.

At one point, a coworker and I realized that there were more works by unknown artists than there were from female artists, let alone ‘contemporary’ ones : but I also remember an acquisitions meeting where yet another passel of karaoke modernist paintings by a second rate male artist were being considered for purchase (despite, as I pointed out, one of the people on the committee was the son in law of said artist, and we already had many works by this artist, and many more lesser imitations in this derivative genre. Unsurprisingly, I was asked to leave the meeting…).

I can’t help but feel nobody would be able to make ArtActivistBarbie leave, in a similar situation (yes, I am smiling as I type that). A performative persona of Dr Sarah Williamson, it feels appropriate to speak of ArtActivistBarbie as a person, unto herself, in this essay.

If you’re still swimming in that cesspool known as Twitter – sorry, ahem, ‘X’ – then perhaps you are already familiar with ArtActivistBarbie (@BarbieReports) who “has a finely tuned eye when it comes to calling out gender inequality in the arts, and she is not afraid of making a scene. Her provocative wit and fabulous wardrobe lend themselves to staged interventions, predominantly in art galleries and museums. Posing with her tiny, pithy placards, ArtActivistBarbie is photographed gently mocking or drawing attention to problematic exhibits and the images are shared with millions of Twitter users. She also challenges the biases inherent in so many curatorial labels and statements.

ArtActivistBarbie seeks to change the practices of these institutions, the bulk of whose collections have historically been commissioned and produced by men, representing many centuries of male power and privilege. Over 94% of artworks in publicly funded galleries [in the UK] are by white men and many objectify and demean women and girls. Making visible the lives and experiences of women and minority ethnic groups is vital for a more just and equal society.” (from here)

The origin of ArtActivistBarbie is thus : “The woman behind the project is Sarah Williamson, a senior lecturer in education and professional development at the University of Huddersfield. A few years ago, she was trying to find a way to engage her students with social-justice issues and feminist ideas, especially the problematic way women are portrayed in art. She wondered if Barbie, that plastic idealised woman, could become a vehicle for playful commentary on the “patriarchal palaces of painting”. Soon Williamson was gathering a doll army, clothing it in pieces handmade by her feminist mother in the 1970s, with new additions created by her sister. She handed each of her students a Barbie doll and a blank placard on a lollipop stick, then set them loose in Huddersfield Art Gallery.

The resulting mini-protest signs stopped visitors in their tracks, and the photographs of Barbie’s protests drew plenty of notice back in Williamson’s office: “I realised I had something which attracted everyone’s attention and catalysed conversations about how women are portrayed and represented not only in art, but society in general.”” (from The Guardian)

It’s also necessary to consider how “museums are somewhat newly self-reflexive about their role in shaping the culture and the discourse, and are working hard to stay relevant and expand the canon—and to grow their audiences.” (That’s from a recent article in ArtNews that appropriately decries the slipshod ‘critique’ offered by the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition Pablo – matic – and although ArtActivistBarbie seems to ‘shoot from the hip’, her aim is more accurate, and considered, in the larger discourse of whom and what cultural institutions serve – and don’t….)

Much more about ArtActivistBarbie’s caustic yet comedic commentary (comedy, it has been said, is just rage in fancy dress, and Barbie has no shortage of snazzy outfits) can be enjoyed here. There are a number of interviews with Dr Williamson that are as educational as they are engaging.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Tish Murtha | Elswick Kids | 1978

August 4, 2023Tish Murtha | Elswick Kids | 1978

All we wanted was everything. All we ever got was coal.

(Bauhaus, from the album The Sky’s Gone Out, 1982)

Patricia Anne “Tish” Murtha (1956 – 2013) was a British photographer best known for her images of working class life in Newcastle upon Tyne and the North East of England. Murtha’s work is a raw documentation of these communities – and often youth within these social groups – at a time when British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher waged war on her own citizens, embracing a neo – liberal cruelty that is like a virus whose symptoms can be still seen in contemporary post Brexit Britain.

The images captured by Murtha evoke notions of a ‘third world’ country, with the scenes of desolate and despairing youth amidst a wasteland that – being shot in black and white – emit a hopelessness that reaches across the decades. Or perhaps it is simply combining with the contemporary desperation among working class communities in these places now.

From here : “In 1976, aged 20, Tish left home to study at the famous School of Documentary Photography at The University of Wales, Newport under the guidance of Magnum member David Hurn.

She took many photos in Newport, including The former Prime Minister James Callaghan opening up a new stretch of the M4, as well as documenting Aubrey Hames’ year as Mayor of Newport in the Queens Silver Jubilee year (1977-1978). Tish also worked with the South Wales Argus during this time and photographed the local election campaigns.

When she returned to Newcastle, she began to document the lives of her friends and family and numerous other projects.

Tish’s work was often concerned with the documentation of marginalized communities from the inside. She invested her time building relationships of trust, which allowed her access to different parts of the communities that she photographed. Her approach was informal, generating an understanding of what she was doing by giving copies of her photos to the people in them. The young people she photographed as part of the Youth Unemployment and Juvenile Jazz Band exhibitions showed how tenacious, resourceful, clever and resilient they were (and had to be) – Tish was always fiercely protective of them.

She felt she had an obligation to the people and problems within her local environment, and that documentary photography could highlight and challenge the social disadvantages that she herself had suffered.”

Three books of her photographs have been published posthumously : these are Youth Unemployment (2017), Elswick Kids (2018) and Juvenile Jazz Bands (2020).

More of Tish Murtha’s work and her life (as her daughter is maintaining her archive and ensuring her mother’s work is given its appropriate place in terms of history and art) can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments