In: art

The Great Texas Road Story | Stephen Hood

February 25, 2023The Great Texas Road Story | Stephen Hood

IG: @thegreattexasroadstory

https://www.thegreattexasroadstory.com/

I refuse to remember the dead.

And the dead are bored with the whole thing.

But you — you go ahead,

go on, go on back down

into the graveyard,

lie down where you think their faces are;

talk back to your old bad dreams.

(Anne Sexton, A Curse Against Elegies)

Well, I see your light’s still on, so I guess you must be out there. It’s okay if you don’t want to talk, you know. I don’t want to talk either, sometimes. I just like to stay silent. (Nastassja Kinski | Jane Henderson, from the film Paris, Texas)

The scenes that make up The Great Texas Road Story are cinematic. This is not just the nature of the vignettes captured, but that encountering this work on IG, it is like a continuing tale, with missives ‘sent’ to us, like an ongoing conversation or ‘postcards’ in a continuing narrative….

They have a quality of scouting locations for a film, but I will admit that I’m bringing in my subjective response, again.

Looking at some of these, I’m – obviously, due to the title of the endeavour – reminded of the fine cinematography of the film Paris, Texas, by Robby Müller. But I’m also reminded of the television series Carnivàle, where a travelling carnival trudges across the United States amidst the arid dustiness and despair of the Dust Bowl Depression. Like the moments photographer Stephen Hood presents in The Great Texas Road Story, the episodes in that series are named after the small towns they traverse – and it all starts in Marfa, Texas, in an odd synchronicity to Hood’s travels around Texas for this project. Looking at the site for The Great Texas Road Story, empty places like Spur and Snyder might be Marfa – or vice versa.

And in the end, these places – despite their evocative physical presence captured by Hood – are also characters in a story, repositories for memories and ideas both personal and more public.

“The Great Texas Road Story is an ongoing photography project devoted to the authentic small Texas town. I aim to continue to artistically capture the places in Texas I find compelling and to share that work here.

This photography project began organically in June 2020, when suddenly, I had to get out of town with my girlfriend, as we hadn’t left our tiny Austin apartment in months, and we needed to do something. Had to go. So we booked a campsite at the state park and headed out west to camp in the Davis Mountains near Marfa. A good ole Texas road trip (soothes the soul) was soon underway.

Our first stop was San Angelo, where we saw a porcupine. I brought an old camera and started photographing the landscape of Texas. I hadn’t picked up a camera in months, but from then on, we were on the road every other weekend documenting all of the small towns along the way.

I only moonlight as a Texas documentarian…It is in my spare time that I lovingly chronicle a disappearing Texas.” (Stephen Hood)

That’s an excerpt of Hood’s description of this work, and more of his images can be seen here: but you’ll be able to enjoy more of these moments if you give The Great Texas Road Story a follow on Instagram here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Krydor, SK | Danny Singer, 2014

February 17, 2023Krydor, SK | Danny Singer, 2014

I would walk to the end of the street and over the prairie with the clickety grasshoppers bunging in arcs ahead of me, and I could hear the hum and twang of wind in the great prairie harp of telephone wires. Standing there with the total thrust of prairie sun on my vulnerable head, I guess I learned — at a very young age — that I was mortal.

W. O. Mitchell, Who Has Seen The Wind

I first encountered Danny Singer’s work in an exhibition in Saskatoon curated to mark the centennial of the province at the Mendel Art Gallery. Most of the artists included had celebratory discourses at play about the place in their work, but there were a few more factual as regards the history – and present – of that province. The Mendel Art Gallery (now the Remai Modern), under the curatorial eye of Dan Ring at that time, often eschewed banal propaganda for more real dialogue, as with the 2002 exhibition Edward Poitras: Qu’Appelle: Tales of Two Valleys. That exhibition’s title “refers to two valleys: a metaphor for the way First Nations and colonists, both past and present, constructed and experienced nature, spirituality, and culture through the physical reality of the Qu’Appelle.” (from the curatorial statement for the exhibition by Dan Ring).

This also acts as another ‘place’ to stand and consider Singer’s ‘sites’, too.

Singer’s works have an element of the performative: if you’ve ever been to the small towns – or similar ones – he’s documented in Saskatchewan and Alberta, you know that they are sparse, spaced and dying, if not already dusty corpses featured in a form of photographic nostalgia that has an element of necrophilia.

Other works in this series shift the camera so that the sky dominates the majority of the composition, so solid and blue it looks hammered into place, with clouds moving like the ocean, and the towns almost miniscule below all of this. Mitchell’s sentiment about the transience of humanity in the face of the eternity of nature is at play in those works, too.

“In Singer’s large-scale composite photographs, there is a real tension between the assumptions of photography as a medium – the fixed point of the camera, capturing a single moment in time – and the reality of the artist’s process, which takes hours and involves hundreds of vantage points. To the viewer, the photographs have a collapsing effect: the passage of time witnessed in a single glance.

The Vancouver-based artist has spent fifteen years photographing the main streets of small towns and hamlets across the prairies and plains of North America, drawing attention to the rural, agricultural communities on which Canada’s economy was built. In these large-scale works, strings of vernacular buildings are dwarfed by a dynamic sky, which fills the visual field. Out of the frame, one can imagine the horizontal repetition of this diminishing effect—farmland stretching hundreds of miles in either direction.” (from Galleries West)

More of Singer’s work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Bison Greeting (detail from Wildlife) | Sunaura Taylor, 2014

February 10, 2023Bison Greeting (detail from Wildlife) | Sunaura Taylor, 2014

“And you took the patronizing tone of an animal-trainer. Have you any idea what it is like to be spoken to in the way people speak to animals? A fascinating experience. Gives you quite a new feeling about animals. They don’t know words, but they understand tones. The tone people usually use to animals is affectionate, but it has an undertone of ‘What a fool you are!’ I suppose an animal has to make up its mind whether it will put up with that nonsense for the food and shelter that goes with it, or show the speaker who’s boss. That’s what I did.”

(Robertson Davies, World of Wonders)

I was introduced to Sunaura Taylor’s artwork by a friend who is a minister, and whose ministry is often focused upon the vulnerable in our Niagara community. We often share artists that interest us back and forth, as my own knowledge of contemporary religious painters appeals to her more progressive sensibilities. This image has a specific resonance to me. After spending so much time on the Canadian prairie the history of the use and abuse of the buffalo – and ideas now that tie buffalos metaphorically to different ways of thinking about society and our actions within it (through an Indigenous lens) with an aim to being ‘better’ and more inclusive as citizens within nations states – are factors in looking at Taylor’s painting.

Taylor’s visual art is striking, offering narratives that are both personal and offer a wider commentary on contemporary society. She is the recipient of a 2008 Joan Mitchell Foundation Award.

Her words: “My paintings are not at all only about the body, but the body is inevitably an aspect of my relationship with whatever it is that I am seeing.”

More: “I also want to paint and see politics, because I was born into them. I have a rare congenital disability called Arthrogryposis that was caused by toxic waste contamination in our groundwater, from the world’s largest polluter, the US military. I use a wheelchair for mobility and my mouth to paint. I grew up in a household of artists and anti-war activists, which perhaps made the knowledge that my body was formed by the industry of war, even more traumatic. I began at twelve to express myself and deal with these emotions through paint.”

Both quotes are from here, and I encourage you to visit that site to consider more of her erudite commentary, and see more of her paintings there.

“Sunaura Taylor is an artist, writer, academic, and an activist for both disability rights and animal rights. Her artwork has been displayed internationally and she is currently an assistant professor at UC Berkeley where she teaches classes in animal studies and environmental justice.

Taylor utilizes her lived experience as a disabled person to present new ways of thinking about disability and animals. Through each strand of her multifaceted work, she examines and challenges what it is to be human, what it is to be animal, and how the exploitation and oppression of both are entwined.” (from here)

While considering Taylor’s work, I was also reading Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our Future by Patty Krawec (interestingly, this book was suggested to me by the same friend who introduced me to Taylor’s artwork): there is a story she relates that I’d like to end with, as a final response to Bison Greeting.

“In the spring, the people laid their tobacco on the ground as an offering, and they prayed and sang. Then they sent out runners in the four directions looking for the deer. These runners ran and ran, covering great distances, and one by one they returned. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing. Finally—maybe because this is how it is in stories—the last runner came back and said she had found one young deer, far to the north. This young one had told her that the deer had felt disrespected and threatened. So they left.

The young deer explained that initially they had waited to see if the humans would remember what we knew. But seeing from our behavior that we had no interest in relationship, and no interest in maintaining the agreements we had made with them, they left. This must have been a difficult decision because of the promise that they had made to the Creator that they would take care of us. The deer needed to think about their own survival, though. If we killed them all, they wouldn’t be here to take care of us anyway.

The people sent their diplomats, their elders, and their ceremonial people to meet with the deer, and for as much time as it took, they listened. They listened to the stories and to the harm they had done. They listened to old relationships and memory. They listened to how things should be. They made offerings and agreements.

Only then did the deer return to them. The people agreed to live in respect for the deer. They agreed to take care of the relationship that takes care of them.”

More of Sunaura Taylor’s artwork and writing can be found here and here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

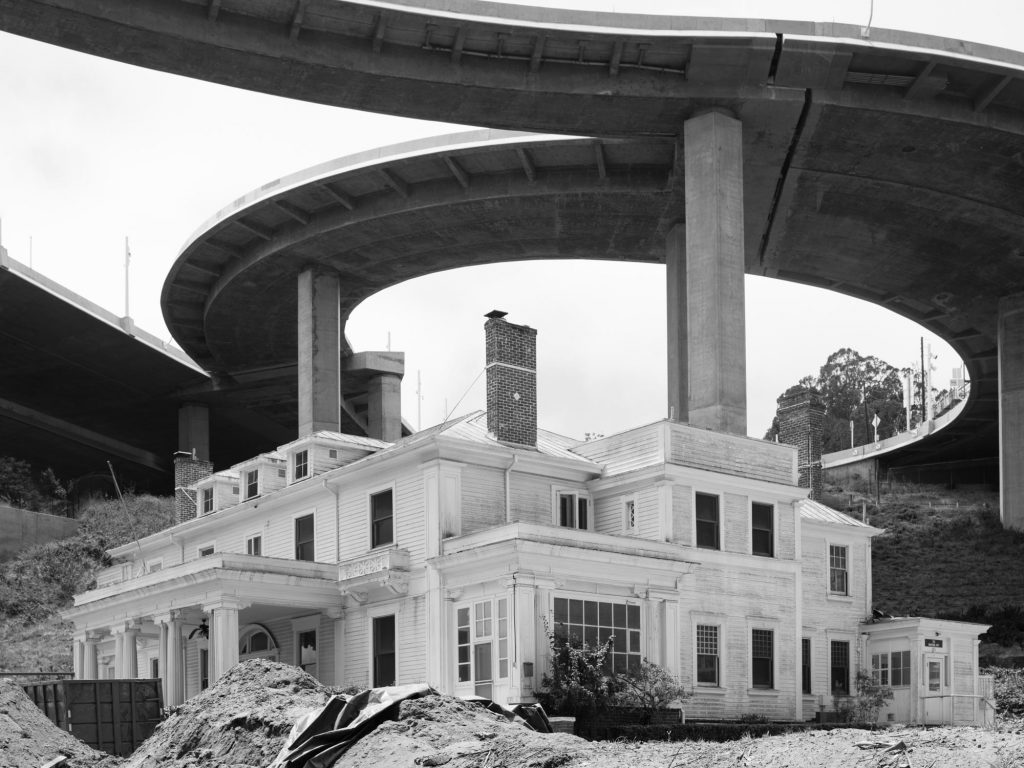

Mimi Plumb | The Golden City, 1984 – 2020

February 2, 2023Mimi Plumb | The Golden City, 1984 – 2020

So this is where the Renaissance has led to | And we will be the only ones to know

So take a drive and breathe the air of ashes | That is, if you need a place to go

If you have to beg or steal or borrow | Welcome to Los Angeles, City of Tomorrow

(Phil Ochs, The World Began In Eden And Ended In Los Angeles)

When I first encountered Plumb’s images, that song from the late Phil Ochs came to mind: it seems upbeat and pleasant but is, in fact, nuanced with a despair that is subtle but builds (and I will admit my interpretation may be coloured by his suicide. But the rendition of that song I am familiar with is a live version, and Ochs talks at the beginning of his fascination with Los Angeles “which intrigues me like a sensual morgue.” Plumb’s works have a certain sterility, to them, as well, that intersects with this consideration).

As with Plumb’s scenes, there’s more at play than the obvious. Considering that California exists in imaginations just as vividly – if not always accurately – as any seminal ‘place’ like ‘Siberia’, Plumb’s photographs invite us to construct narratives around them, that build, converge or perhaps complete what she intends, with her own personal stories….

I will admit that when looking at Mimi Plumb’s photography, that The Golden City often blended with another body of work of hers, titled The White Sky. I doubt that the artist would be offended by that, as the elements of memory, nostalgia and social realism suffuse her practice, and are themes that are present in her artwork still. Although her narrative is a personal one, it also has elements that are more universal, when considering larger tropes that her work touches upon.

“The Golden City [is] a series of images that frames subjects against the sprawling backdrop of San Francisco. Similar to Plumb’s other bodies of work, The Golden City is an ode to an earlier America—a rich and playful elaboration on the human condition, and its tendencies towards hedonism and spectacle. To say that this work largely references the exploitation of the natural world on account of humans would be reductive. While sculptural detritus and empty construction sites set the groundwork for this series, Plumb flips dramatic irony on its head by capturing subjects enthralled by events transpiring just beyond the frame. We are not in on the comings and goings within this world, but are sucked in nonetheless; left only with a sense of wonder at what could be bringing about such awe.” (from Document, with an engaging conversation with Plumb you can read as well)

Much more of Plumb’s work – from this series and a number of others – can be seen here. If you’d like to listen to her talk about her work, the Museum of Contemporary Photography has a video you can enjoy here.

Plumb published a book of selected images from this body of work with Stanley/Barker books in 2022.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Komar and Melamid | Yalta Conference, 1982

January 26, 2023Komar and Melamid, Yalta Conference, from the “Nostalgic Socialist Realism” series, 1982

I enjoy speculative fiction and recently was reading Harry Turtledove’s Joe Steele. It’s a stand alone story, but you may be familiar with his Southern Victory series (in which the Confederate States survive the American Civil War, and it stretches into the mid twentieth century, offering alternate – yet familiar – takes on everything from WW I to the Holocaust) or World War / Colonization books. That series of books inject an alien invasion into the midst of WW II. This might sound ludicrous, until you read them and one of the aliens observes that – upon their discovery of Buchenwald and Auschwitz – that clearly humans are monstrously incapable of governing ‘ourselves.’ It’s an interesting tonic to the proliferation of science fiction that posits an alien deus ex machina that proffers the narrative that humans are special – such as Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, for example. Perhaps it’s because Clarke was more hopeful, and much has happened since then…

“The novel [Joe Steele] explores what might have happened had Joseph Stalin been raised in the United States, postulating his parents having emigrated a few months before his birth, instead of remaining in the Russian Empire. It depicts Stalin (in this history, taking the name Joe Steele) growing up to be an American politician, rising to the presidency and retaining it by ruthless methods through the Great Depression, World War II, and the early Cold War. The president is depicted as having the soul of a tyrant, with Stalin’s real-world career mirrored by actions taken by Steele.” (from here)

But I mention Turtledove’s Joe Steele as it reminded me of Komar and Melamid’s painting Yalta Conference, from the Nostalgic Socialist Realism series, 1982. This work has also been the cover image for Boris Groys’ seminal book The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond (2011). The ‘inspiration’ for this painting is a famous photograph.

Komar & Melamid are interesting for their cultivated personas as much as their art. This painting can’t help but offer and foment a myriad of interpretations, drawing upon not just the ‘players’ but the moment it re imagines. Yalta was, after all, the point at which the shaky alliance between the USSR and the United States began to seriously fracture. The employment – or appropriation – of ‘socialist realism’ (a style that was the official style of the USSR but that – to quote a Soviet born historian – was like Pravda, in that you can find some grain of truth by what it ignores) only makes this a ‘scene’ even more about failure (like the Yalta Conference was, towards any peace in a Post WW II world) than progress, with a sprinkling of absurdity and skepticism, with the hushing Hitler and American leader a goggle eyed alien….

Boris Groys, in writing about Komar and Melamid, offered the following about their aesthetic: “[The artists] themselves, however, perceive no sacrilege whatever here, because they consider the religion of the avant-garde to be false and idolatrous.”

More from Groys, that could also apply to this painting, and the multiplicities of potential interpretations of it (combined with the irreverence of Komar and Melamid’s larger practice): “[in] the West, the march of progress is “aimless” – one fashion succeeds another, one technical innovation replaces another and so on. The consciousness that desires a goal, meaning, harmony, or that simply refuses to serve the indifferent Moloch of time is inspired to rebel against this progress. Yet the movement of time has resisted all rebellions and attempts to confer meaning upon, control, or transcend it.”

More of Komar & Melamid’s work – and their unique aesthetic and legacy – can be enjoyed here. If you’re interested, more about Boris Groys’ writings and ideas can be read here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

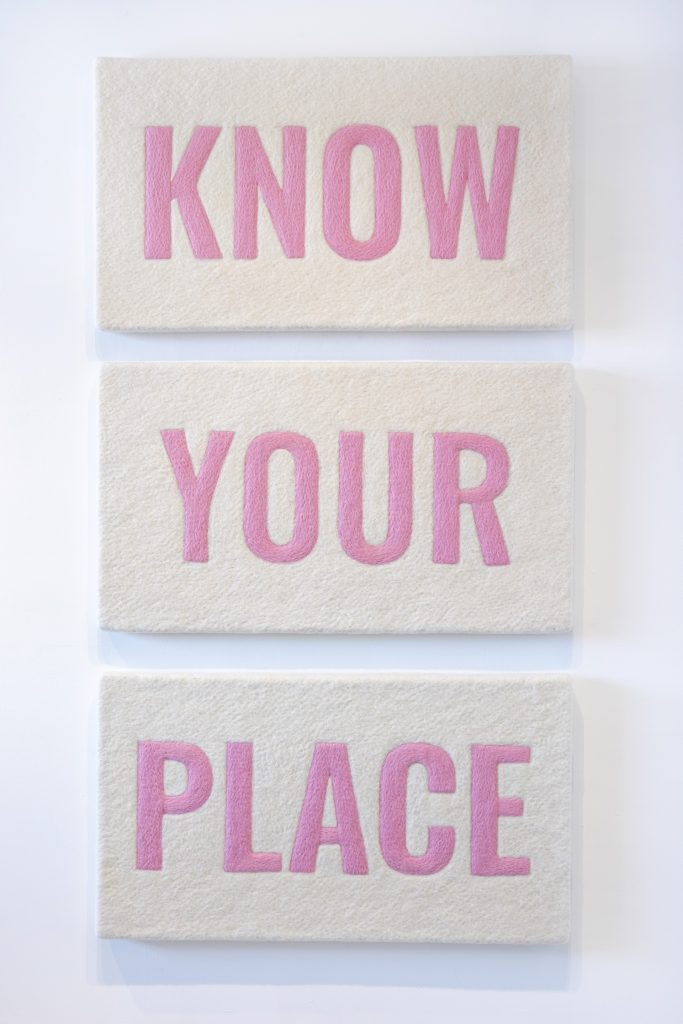

Kelly Tapìa – Chuning | More Than Once, 2022

January 20, 2023Kelly Tapìa-Chuning | More Than Once, 2022

needle felted Romney wool on foam board insulation, 27.50 x 49 x 4 inches

I could pretend I’m sorry for saying this (but I’m not, in the least), but 2023 has been off to an interesting start with the deaths of Joseph Ratzinger and Gerald Pell. Perhaps you think that’s ghoulish, but when considering the work of my latest Curator’s Pick – Kelly Chuning – I remembered that not just had both of those men aided and abetted abusers of children, but their lives and actions were drenched in misogyny. Their hatred of women who didn’t fit their own ignorance is one of the many rank stenches that they’ll leave behind, akin – if not worse – than the smell of a corpse.

If that seems ‘disrespectful’, let us consider the artwork by Tapìa – Chuning that spurred these thoughts, which were in an exhibition titled What is Respect? that was at Red Arrow Gallery in 2022.

“What is Respect? takes place two months after the Supreme Court overturned Roe V. Wade, guaranteeing a women’s right to an abortion and 5 days before abortion is completely illegal in the state of Tennessee. With this body of work, I am giving the responsibility to the viewer to decide what the term ‘respect’ implies, given the current political climate; and asking the audience to consider how we can utilize language as a tool for change going forward.

Growing up in a fiercely religious household, the people of Tennessee weighed heavy on my mind as I heard the news of the state’s trigger law (‘The Human Life Protection Act’) banning abortion with no exceptions for rape or incest. As a victim of sexual assault, the implications of this law influenced me to act immediately.” (from here)

It is necessary to remember that the voices on the Supreme Court of the United States that spewed the Dobbs decision are predominantly religious – with ‘precedent’ being ‘cited’ by one, the rabid catholic Alito, regurgitating the biliousness of a witchfinder from several centuries ago. If my writing seems caustic – or ‘disrespectful’ – it is less so than those that seek to dehumanize people like Tapìa – Chuning…..

Kelly Chuning is an interdisciplinary biracial Latinx artist currently based in northwest Montana. She received her BFA in Studio Arts from Southern Utah University and will be attending Cranbrook Academy of Art fall 2022 as a Gilbert Fellow. Chuning’s work explores rhetoric, imagery, and media as a tool of constructing various modes of female identity.

Her IG is @kelly_chuning/

Kelly Tapìa – Chuning’s site is here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Romina Ressia | Woman with a Water Pistol, 2014

January 6, 2023Romina Ressia | Woman with a Water Pistol, 2014

Most of the writing around Ressia’s photographs talks about absurdity and anachronism: perhaps that’s because she appropriates form and redefines meaning in a manner that challenges art historical tropes around gender and relevance. Meticulously executed, her ‘portraits’ have a gravitas on the one hand, but then this is broken by elements that can’t help but amuse (though her people never crack a smile, with eye contact that might wilt any irreverence from the viewer).

There is a hint of dourness to the woman who is the player in this series, and many others, having a heavy handed seriousness that is then fractured by the various objects her subjects are brandishing that seem silly and puerile.

Bluntly, Messia’s Woman with a Water Pistol looks like she’s had just about enough of you, young man, and unless you want to be sprayed with water – disciplined like an unruly, disobedient cat – you’d best behave. You shan’t be told again.

A bit flippant perhaps. But consider the [still, uninterrupted] proliferated misogyny in Western art history [or contemporary art] of women as object, or demure commodity, or the validation / apologia of rape as seen with Europa or the Sabine women or ‘Susannah and the Elders’ (and so, so many others). Consider that in (recently done) 2022 we’ve seen groups of women around the world make it clear that they have had *quite* enough and my interpretation is not without consideration….

This image is part of a larger series titled How would have been Childhood? with the same figure in them all, her unimpressed body language acting as a unifying aspect of the artworks. Birthday hats, costumes, balloons – nothing seems to inspire joy, here. When I first encountered this series online, a birthday party that no one was enjoying – if anyone even came, besides the ‘star’ of the series – can be forgiven for being an initial impression….

“Romina’s art cleverly initiates dialogue on important contemporary social issues through the striking use of anachronistic tropes juxtaposed with mundane and banal elements of modernity. Indeed, the influence of classical artists like Da Vinci, Rembrandt and Velazquez is instantly recognizable in the palettes, textures, ambiance and scenes captured in Romina Ressia’s works, bequeathing them an air of familiarity which only serves to highlight the contradictory and sometimes confrontational presence of objects of modernity such as cotton candy, bubble gum, microwave popcorn and Coca Cola.

The theatrical absurdity in her pictorial compositions, which combine stylistic elements of Renaissance paintings and Pop art, and the dissonance of the stark contradictions captured therein have a surprising clarity, making for an honest critique through visual dialogue of received notions of modernity. In this sense, Romina succeeds in achieving her artistic intent which is not to recreate or refer to the past but to establish a frame within which to interrogate the perceived evolution and progress of society especially in respect to the role and identity of women.” (from here)

If you’re doltish enough to suggest ‘she’d look better if she smiled’, don’t be surprised if you get soaked – deservingly.

More of Romina Ressia’s evocative – if a bit disquieting – work can be seen here.

Her Instagram is @rominaressia

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Dan Kennedy / Dr. Erosion | Animations, 2019 – 2022

December 15, 2022Dan Kennedy / Dr. Erosion | Animations, 2019 – 2022

I’ve always been a fan of animation in its many forms (I am a member of Gen X, so Saturday morning cartoons shaped me, but I also remember watching Science Ninja Team Gatchaman – and the butchered Western version Battle of the Planets when small, and Akira [アキラ] is another seminal experience, for me, when young).

Speaking as a more mature viewer, The Brothers Quay’s Street of Crocodiles (1986) is something I can watch over and over: and recently I rediscovered the 1986 animation The Mysterious Stranger, from the larger film The Adventures of Mark Twain (that vignette is based on Twain’s ominous story of the same name). The shifting mask of Satan, in that claymation, disturbed me as a child and still horrifies me now. Perhaps, with stop action animation, there’s that same ‘perversion’ of the human body that we see in work with dolls, as I touched upon when responding to Gabrielle de Montmollin’s Weird Baby World installation.

When I began researching Dan Kenndy / Dr. Erosion’s work, I was mostly familiar with his two dimensional ‘still’ artworks, but soon became engrossed with his short ‘films’. Drawing Time, Cats Dream of Water, Where is the Blue Fairy? – and many others – are brief visual anecdotes, amusing and disturbing simultaneously.

The images below are teasers for the longer works, which can be enjoyed here (works from 2019) and here (works from 2020 – 2022).

Kennedy’s aesthetic is ghostly ethereal and densely complicated, pulling upon his continuing “explorations of commercial culture or as he refers to it, ‘the commercial unconscious”.” (from here) There are hints of Hieronymous Bosch in these brief vignettes from Dr. Erosion / Kennedy that are engaging but also eerie.

When I’ve written about abstract painting I’ve often stolen and shared an idea from art historian Julian Bell: ‘In other words there was no prior context to the painting itself. The viewer’s eyes would submit, and the painting would act.’ Kennedy’s works are often short, and this makes them even more focused – like a sharp taste, where more would be too much.

Dan Kennedy / Dr. Erosion was also a previously featured Artist You Need To Know in AIH Studios’ continuing series. That can be explored here.

IG: @dr.erosion

https://www.dankennedy.ca/

More animated works from Kennedy / Dr. Erosion can be found on VIMEO.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

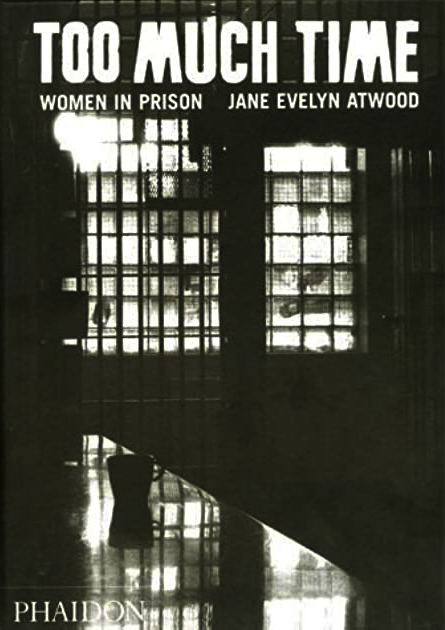

Jane Evelyn Atwood | TOO MUCH TIME: WOMEN IN PRISON, 2000

November 25, 2022Jane Evelyn Atwood, TROP DE PEINES: FEMMES EN PRISON, 2000, Éditions Albin Michel, Paris, France. (OUT OF PRINT)

Jane Evelyn Atwood, TOO MUCH TIME: WOMEN IN PRISON, 2000, Phaidon Press Ltd., London, England. (OUT OF PRINT)

“Curiosity was the initial spur. Surprise, shock and bewilderment soon took over. Rage propelled me along to the end.”

Too many times – and I’m sure I’m not alone in this – I have heard some well meaning dilettante assert that ‘art should be about beauty’ or ‘should only uplift us.’ In terms of that space where photography intersects with ideas of art and documentary – and not to mention history – something that comforts you is most likely wrong, if not simply pablum. When I’m sharing images on social media, there are some photographers I hesitate to post works from (as photography still carries the weight of being more ‘real’, thus can ‘offend’ as well as see yourself banned from those platforms): Gilles Peress is one of those, for his unflinching lens in places from Rwanda to the former Yugoslavia (“I don’t trust words. I trust pictures”), Gordon W. Gahan (specifically his images of the Vietnam War), Donna Ferrato (I was lucky enough to experience her groundbreaking series Living with the Enemy decades ago, in Windsor) or Martha Rosler (her House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home works that had their genesis in response to the Vietnam War (c.1967–72) but that she ‘revisited’ in 2004 and 2008, ‘updating’ them to Iraq and Afghanistan).

But the text I’ve selected for a Library Pick is something that is not ‘there’ but ‘here’, and in that respect is often – easily, repeatedly – ignored.

Jane Evelyn Atwood’s “monumental work on female incarceration, published in both French and English, took Atwood to forty prisons in nine different countries in Europe, Eastern Europe, and the United States. The access she managed to obtain inside some of the world’s worst penitentiaries and jails, including death row, make this ten-year undertaking the definitive photographic work on women in prison to date. Extensive texts include interviews with inmates and prison staff as well as Atwood’s own reminiscences and observations. The prize-winning photos in this book, including the story of an incarcerated woman giving birth while handcuffed, established Jane Evelyn Atwood as one of today’s leading documentary photographers.” (from her site)

Atwood has always used her camera as a means to tell stories too often not even dismissed but denied, and she has granted a level of dignity and consideration to those whom are too often not considered human but detritus.

A good friend is a theologian, but of the liberation theology vein: I enjoy talking with them, as their righteous anger is only matched by their ability to quote that repeatedly translated and edited text with a sense of the public good. I mention them as they once pointed out that in the New Testament, only one person was promised a place in the ‘kingdom of heaven’, and that was one of the criminals being crucified at the same time as Jesus.

In a more modern sense, I might cite Lutheran Minister (and ‘public theologian’) Nadia Bolz-Weber‘s contemporary addendum to the beatitudes, which include ‘Blessed are those who have nothing to offer. Blessed are they for whom nothing seems to be working.’

Atwood published ten books of her work and been awarded the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography, the Grand Prix Paris Match for Photojournalism, the Oskar Barnack Award, the Alfred Eisenstadt Award and the Hasselblad Foundation Grant twice.

More of Atwood’s work can be seen here.

Like several of the books I’ve recommended, this is one I came across in my local library.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Arthur Tress: Fantastic Voyage, Photographs 1956-2000 | 2001

November 10, 2022Arthur Tress: Fantastic Voyage, Photographs 1956-2000

200 pages, Hardcover, Bulfinch, 2001.

Arthur Tress (Photographer), with writing by John Wood and Richard Lorenz

There was a recent exhibition of Tress’ photographs mounted at Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto, and that brought his work back to mind. Having enjoyed several of his books, I returned to this one – which is, for me the definitive publication of Tress’ art and aesthetic – and it’s definitely worthy of a Library Pick.

Tress’ works are striking, if unsettling. An initial amusement or facile reading gives way to a more conflicting or uncanny narrative upon closer consideration. He shares this with photographers like Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Mary Ellen Mark, Diane Arbus and – an artist featured in a previous Library Pick – Roger Ballen.

“Tress started out as an ethnographic documentarian but, partly inspired by the rituals he recorded, turned to ever more premeditated subjects. In an early project, he asked New York children to tell him their dreams and then posed them, with appropriate trappings, in neighborhood spaces to illustrate their sleeping fancies. His projects since the mid-1980s involve arrangements of tools, toys, furniture, dolls, and other stuff that Tress paints and lights to suggest scenarios and even narratives. Besides the short-term projects, Tress has made surrealist outdoor still lifes and male nudes over longer periods. The latter, including some of his best-known pictures, are implicitly homoerotic but considerably more apprehensive and even dread-filled than the nudes of fellow gay surrealist Duane Michals. But there is more humor and less darkness in Tress’ highly polished work…” (from Tress’ site, which is worth spending some time exploring, as well)

“Arthur Tress’s career can be seen as a long fantastic voyage – from early photojournalism into the realm of surrealism, eroticism and miniature worlds. This retrospective is an overview of Tress’s career. As the title implies, Tress’s work is full of fantasy – nothing is what it at first seems. His images contain dark undercurrents and light wit, violence and beauty, futuristic scenes and homoerotic and psychologically charged tableaux. The 250 images featured in this volume range from the early black-and-white work to the richly coloured surrealistic images of the 1990s and his latest, previously unpublished work in progress. Richard Lorenz, (curator of a retrospective exhibition in Washington, DC, in May 2001) offers an in-depth biographical essay on Tress and the development of his vision. An essay by noted photo critic John August Wood puts Tress in context.” (from here)

The images I’ve shared here are from the bodies of work by Tress that are my favourites – primarily Dream Collector (1970 – 74), Theater of the Mind (1976 – 77) and Still Life (1981 – 83): but there’s other series in this book that are very different, and a testimony to the breadth of his aesthetic and career. These include the starkness of his documentary work in Appalachia (1969) to the uncanny quality of his Fishtank ‘installations’ (1989) to the moribund garishness of Hospital (1985 – 87).

From the Corcoran’s review of this publication: “Tress’s work, above all else, reveals a personal approach to photography, a subjective view of the world that continually reinvents itself while it ponders universal archetypes and myths.”

Arthur Tress was a previously featured artist in AIH Studios’ ongoing Artists You Need To Know series: that can be enjoyed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments