In: art

Geoff Farnsworth | Frank Auerbach, 2021

April 13, 2023Geoff Farnsworth | Frank Auerbach, 2021

But this rigour could be seen as revolutionary, one requiring a major historical shift from an art of representation to one of presence, that is, the direct experience of the object standing before you.

Julian Bell, What is Painting? Representation and Modern Art

Let us begin with a disclaimer that is, in fact, a compliment. I am not featuring my friend and the fine painter Geoff Farnsworth’s work because he has painted me twice (he has rendered, wonderfully, in paint, a number of denizens of Niagara), nor because the most recent of these is almost perfect in capturing the moment and conversation we were having (he snapped a picture at that time) and the vagaries of my overly expressive face and demeanor. I won’t tell you what we were discussing at the time (along the road in Welland) but my unimpressed face in that work tells you all you truly need to know, of the moment.

Farnsworth has demonstrated that ability on numerous occasions, to not only bring a telling likeness of his subjects into his paintings, but also to seemingly embed an element of their personality, too. A fine painter who dances between figurative works and hints of abstraction with an affinity for colour that defines his art.

His portraits seem to coalesce from his thick, mucoid paint, with a figure emerging from his rich colours and almost sculptural application of his medium. The image vascillates between abstraction and representation, and in this work – as it is a portrait of the painter Frank Auerbach – that dialogue happens not just on the canvas but in the conversation around the choice of subject, and Auerbach’s own ideas regarding non representational and more ‘realist’ painting. But – somewhat in opposition to this idea, as all these things blend together like paint on a surface – I’ll return to Julian Bell, whom I cited at the beginning of this essay: ‘ — there was no prior context to the painting itself. The viewer’s eyes would submit, and the painting would act.’

But let’s end by returning to Auerbach (from Frank Auerbach Speaking and Painting by Catherine Lampert): “Auerbach views such claims and labels as essentially meaningless; for him, where figurative art excels, if it is any good, is in what is abstract within the painting and concept. The forms one engages with, and invents, will have a plastic character and individuality unconnected to their names.”

Since I mentioned it in this article, I feel compelled to include an image of the fine portrait that Geoff Farnsworth painted of me, so you might have a visual to augment my words. But I will temper it with an image from Ad Reinhardt, whose ideas about the immediacy of the art object, and the necessity of its primacy in any interpretation of the same is relevant to considering Farnsworth’s portraits, which shift and flow and fracture and come together again, all in colour and line and very physical, goopy ways. Both of these can be seen in the proper post for this artist, not on this front page.

Geoff Farnsworth began his art training in Vancouver, B.C. at the Federation of Canadian Artists, Emily Carr, and Capilano College in the Graphic Design & Illustration Program. He moved to New York City to train at the Art Students League from 1997 to 2002. His paintings have been shown in New York City, Washington DC, Minneapolis, Toronto, Vancouver, Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Niagara Falls, Norway, Sweden, and Trinidad.

His words: “My paintings explore a relationship between figurative and abstraction in order to meld unconscious probing and stylistic innovation with a meditative figural base. It is important to me that the paintings work well as collections of shape, colour, texture, and energy, while also building a compelling image. Working with people and objects from my personal world, I focus on maintaining a balance between plan and accident, known and unknown, restraint and exuberance. My figures look out as much into mindscape as landscape.”

You can enjoy more of Farnsworth’s work here and more of his portrait works (of people both known and more local) can be viewed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Takayo Kiyota | Tama-Chan

April 6, 2023Takayo Kiyota | Tama-Chan

“That’s what you get for being food.”

― Margaret Atwood, The Edible Woman

Takayo Kiyota (also known as Tama-Chan) produces what can only be described as sushi art: some are playful, some are slightly more unsettling and others offer an interesting opportunity for dialogue about our relationship to food and larger assumptions around aesthetics.

In this artwork, Kiyota – who has interpreted famous works such as Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) or Vermeer’s Girl With A Pearl Earring | Meisje met de parel (1665) – re-imagines a painting that is well known but often misconstrued, sometimes in a bawdy manner.

Gabrielle d’Estrées et une de ses soeurs (Gabrielle d’Estrées and one of her sisters) was painted by an unknown artist (perhaps from the Fountainbleau School) around 1594. It can seen in the Louvre, in Paris: “The painting portrays Gabrielle d’Estrées, mistress of King Henry IV of France, sitting nude in a bath, holding a ring. Her sister Julienne-Hyppolite-Joséphine sits nude beside her and pinches d’Estrées’ right nipple.” More about this painting can be seen here.

Years ago, I experienced an audio environment / installation by Anitra Hamilton: the bare gallery space was inundated by two conflicting yet connected audible narratives. One section of the gallery was suffused by a recording of a Sotheby’s auction of artworks. The other was a cattle auction, with ‘prize’ animals going to the highest bidder. In a response to that exhibition I made some uncomfortable analogies to what we consume, how we value it, and the conversations around these things that ‘feed’ us.

Tama-chan (Takayo Kiyota) was born in Shinjuku, Tokyo. After graduating from the Setsu Mode Seminar she started to work in advertisement, magazines, and books as a freelance illustrator. Since 2005, she has called herself the sushi roll artist “Tama-chan.” Through workshops she has been introducing the importance of food culture, food education, as well as the joy of making things with her maki-sushi. In 2013, she won the second prize on “the longest scream in the world” sponsored by Innovation Norway. In 2014, Little More Co. published Smiling Sushi Roll, the first anthology of her work.

You can see more of these delicate and temporary artworks on IG : @smilingsushiroll39

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Pat Douthwaite | Bernard Berenson at Leptis Magna, 1966

March 31, 2023Pat Douthwaite | Bernard Berenson at Leptis Magna, 1966

I am only a picture-taster, the way others are wine – or tea – tasters.

Bernard Berenson

Years ago when I was on a panel talking about ‘modernism’ I offered a line from Clement Greenberg, that is one of my favourites (not solely for the idea expressed, but also as it seemed to fly in the face of many of the karaoke modernists who attended that discussion on the prairies who are sure ‘art’ ended with hard edged painting several decades ago): that we evaluate artwork with the criteria we have now, but fully understanding that this criteria can and must change.

Greenberg is one of the ‘old gods’ of the Western art canon – like Bernard Berenson, the erstwhile subject of this painting by Douthwaite. The site that Berenson is ‘visiting’ in this painting is of significant archeological important (more on that can be read here). Berenson (1865 – 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance, but his influence was much more than that, and he is one of the shoals of Western art history that is to be negotiated.

But – in deference to contested narratives, and considering how Douthwaite has, like too many female artists, not garnered the acclaim of some of her male colleagues – I also offer Atwood’s iconic line: “We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom. We lived in the gaps between the stories.” Douthwaite’s paintings have a striking originality, and though she’s often compared to Chaïm Soutine he is also – like Douthwaite – an artist whose work is immediately recognizable. This painting has a carnivalesque quality to it, and the ‘skulls’ suggest a merry dance of death…. she often “referred to herself as the “high priestess of the grotesque”, aptly describing her dedication to the arresting, often haunting, figurative work that carved out her place within British postwar art…[Douthwaite] was a distinctive and complex artist rather than [simply] a “difficult” woman, as she was sometimes described.” (from here)

Douthwaite’s approach is unique: ‘Instead of the traditional easel set up, Douthwaite preferred to paint on the floor: ‘I crawl around the floor on my knees, with a butcher’s apron round me, moving from drawing to drawing or canvas to canvas.’ She was unconventional in her painting technique too and rather than use brushes she worked the images up from the surface of the canvas using paint-soaked rags. She often depicts death with humour as if to underline the absurdity of life.’ (from here)

Pat Douthwaite was born in Glasgow in 1939 and initially studied mime and modern dance with Margaret Morris. She is primarily self taught, though in 1958 Pat lived in Suffolk with a group of painters. From 1959 to 1988 she travelled widely (North Africa, India, Peru, Venezuela, Europe, USA, Kashmir, Nepal, Pakistan, Ecuador) and from 1969 lived part of the time in Majorca. Douthwaite exhibited with the Women’s International Art Club in London between 1960 and 1966. She returned to spend the rest of her life in Scotland, passing away in 2002 at Dundee. In 2005 the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh mounted a memorial exhibition to mark her life and work.

Much more of her work can be seen here, and more about her life can be learned here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

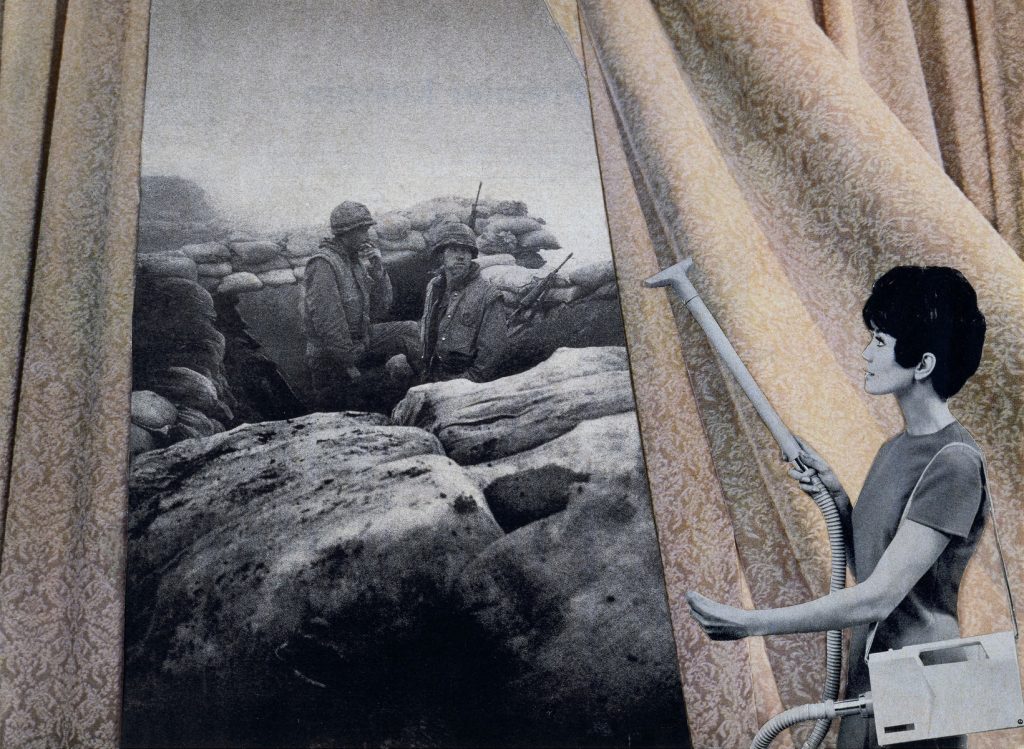

Martha Rosler | House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–1972

March 24, 2023Martha Rosler | House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–1972

Cotton’s generation grew up with a war in the house. For them, games of cops and robbers and cowboys and Indians no longer satisfied the senses. A boy had but to turn a control to be totally involved in the violent distension of experience that was Vietnam on television. Cotton became addicted to it. Vietnam was even a portable war.

A boy had but to move his personal set to have air strikes in the living room, search-and-destroy operations in the bedroom, naval bombardment in the bathroom—napalm before school, body bags before dinner.

(Glendon Swarthout, Bless the Beasts and the Children)

I recently read The Sacred Lies of Minnow Bly by Stephanie Oakes. The premise – of a young woman who survives a doomsday cult – sent me down a rabbit hole, if you will, of research on these cults, and since then I’ve been devouring a number of texts on the topic.

One of these – Jeffrey Melnick, Charles Manson’s Creepy Crawl: The Many Lives of America’s Most Infamous Family – offers an interesting supposition. Melnick argues that the Tate – LaBianca murders were used by many on the right – Nixon, for example – as a means by which to shutter debate about the (even then) failure of the nuclear family in the United States. This is similar to Zizek’s comment that most conversations about socialism always have a chicken little proclaiming it ‘will end in the gulag!’. Other societal issues are cast in a different light from the Manson murders, as well (for example, Melnick talks about the dismissive attitude towards runaways – especially girls – at that time, criminalizing or infantilizing them, using several of the Manson ‘family’ as examples, instead of focusing on larger issues within society).

Melnick dismisses with derision the idea that Manson ‘ended’ the supposed utopic dream of the 1960s – and for this post, a point he makes stays with me. Bluntly, that the violence of the Manson family was nary a drop in the bucket to the televised, sanctioned and officially endorsed violence of the war in Vietnam and other societal pressures. His words: “If the countercultural fabric got torn it was not because a few celebrities were killed in August of 1969. We would be better off attending to the plight of returning veterans, the not unconnected influx of harder drugs into American cities, the ongoing runaway crisis, and a major effort by the dominant culture—from the president on down—to repudiate and abandon young people and their culture.”

And this brings us to Martha Rosler’s series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–72.

The initial incarnation of this series was about Vietnam: in a despairing commentary about history Rosler would revisit and reinterpret it decades later, for the ‘war against terror’ in Iraq and Afghanistan…..

Rosler – in the tradition of artists like Hannah Höch – employs collage, using images that are familiar to us in tandem with others that fracture and trouble the original ‘homes’ on display. These might ‘homes’ in the literal sense, but also the ideologies and assumptions that inform those spaces, sometimes so implicitly that to highlight them engenders a denial of them, like a fish unaware of water as it’s so ubiquitous.

‘This work is one of twenty pieces from Rosler’s House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (c.1967-72) series created during, and influenced by, the Vietnam War. It was the first war in history that was literally brought into the homes of American people through the revolutionary new television set from which its horrors could be witnessed daily. It was often described as a “living room war” – a description loaded with strange poignancy as it shined a light on the eeriness of a nation living their everyday lives, ripe with consumerist concerns like keeping the stylish home drapes clean, all the while gruesome political realities took place elsewhere, becoming just another form of nightly entertainment in front of the tube.

Simultaneously, there is a feminist element to the work as it comments on the robotic mundaneness of female domestic work in the midst of global unrest. The idea of women striving to keep the house beautiful while war’s tragedies are omnipresent becomes almost comical, and presents a surreal picture about what we deem important. Recognizing the potential for manipulation in the photographic medium, Rosler once stated, “Any familiarity with photographic history shows that manipulation is integral to photography.”’ (from here)

More of Rosler’s extensive practice – and her roles as social critic and historian for more than half a century – can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Robin Claire Fox | Reflections

March 17, 2023Robin Claire Fox | Reflections

Photography is inherently nostalgic. Every image taken is essentially the capturing of a moment from the past. That moment no longer exists, just the memory of it and an analogue print or a digital impression trapped on an electronic device. Many modern photographers harbour longings for the saturated or contrasty renderings of images made with processes and media (like Kodachrome) long out of use or no longer in production. Quite a few of them try to recreate the look and feel of these processes digitally, running their captures through filters and algorithms to bring back the visual past. While many are overdone (why keep it at 3 when you can dial it up to 10?), there are a few who have mastered the ability to make us believe that we are viewing an image taken decades ago. The evocation of this photographic past is (I believe) an effort to physically reconnect with it in a way that seems familiar, safe and warm… like sitting with your family watching slides projections of photos from a vacation taken years ago.

Ancaster, Ontario’s Robin Fox started taking photographs around the time of the birth of her most recent child as a conscious attempt to document her family’s childhoods for her future self to enjoy. She is a natural at capturing the uncertainties alongside the joys of growing up. A huge fan of Saul Leiter’s colour work, she has found a method of perfectly capturing the deep saturation and contrast Leiter exhibited in his work with Kodachrome and other slide films[1] in the 1950’s. Her images seem imbued with palettes that exist only in the memory of childhood, where everything was so much bigger and the world was awash with primary colours.

Read More

Jana Sterbak | Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic, 1987

March 16, 2023Jana Sterbak | Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic, 1987

“Adam was left alone. It was then that God created the Second Wife.”

“Yeah? What was her name?”

“Oh. She never had a name, poor thing. God created her for Adam, out of nothingness. Bones first. Then internal organs. Then flesh. Muscle. Sinew. Fat. Bile. Eyes. Snot. Skin. Hair. Breath…

Adam couldn’t bear to go near her. He wouldn’t touch her.

Bodies are strange. Some people have real problems with the stuff that goes on inside them.”

“Jesus. What happened to her?”

“Opinions differ. Most say God destroyed her. A few have claimed that she was permitted to leave the Garden alone.”

(Neil Gaiman, A Parliament of Rooks)

Ah, the controversy, the pearl clutching, the performative gnashing of teeth: back when this work was installed at the National Gallery of Canada, you would have thought that a Canadian government had wilfully allowed a citizen to be tortured or sent body bags to an Indigenous Reserve as a continuing pattern of colonial violence both literal and ideological. To inject my own time in Saskatchewan, it’s not like Premier who has three DUIs where one led to the death of a young mother, or like Indigenous men are being dumped outside the city, in winter, by police.

In tandem with the hypocrisy around the purchase of Barnett Newman’s Voice of Fire (which has only appreciated with age, unlike the money the taxpayers have paid out in unmerited pensions and perks to the ‘politicians’ who whined about it), it was a strange time for the visual arts in Canada.

But now some facts to balance that vitriolic tangent.

“The artwork consists of a “Flesh Dress”, constructed of slabs of beef sewn together, hung on a tailor’s dummy. It is a one-piece, sleeveless, calf-length “house dress”, with a jagged edge. The marble texture of steak and the thick fat are fully visible, displaying its expressive and bloody appearance. On a nearby wall, a photograph of a young woman poses in the dress. The dress is stitched together from 50–60 pounds of raw flank steak and must be constructed anew each time it is shown. Initially, the steak is fresh and fiery red, and then it gradually turned beige and brown, changing its shape and size to conform to the dummy’s hourglass shape. The work included either $260 or $300 worth of meat, as of its 1991 showing.

As suggested by the title, the work is considered within the genre of “vanitas”, a category of art showing death and decay. The work includes non-traditional materials, a trend in 20th-century art. It “stands in the Surrealist tradition of the uncanny….disturbing the distinctions, by which we categorize experience”.

Progressive Conservative MP Felix Holtmann, a pig farmer from Manitoba commented: “I call it a jerky dress. There are a lot of people who hold food sacred in this land, and they are appalled by the use of food for this thing.” In response, one newspaper editorial called him a “meat head”. Holtmann was chair of the House of Commons Communications and Culture Committee, which oversees the NGC funding; the committee itself was split on the issue. The artist called Holtmann a “self-proclaimed Philistine [who is] not even successful as a hog farmer.” Art critic Christopher Hume commented that the committee’s concept “was based on the notion that the National Gallery is somehow accountable for poverty and hunger in Canada. Surely the irony of their desperate position is that they are members of the group that created the mess the country is now in.””

(All of the above from here).

Sarah Milroy – then writing for Canadian Art, now one of the engines driving the Art Canada Institute – observed that reaction would have been very different if the artist had been male. I’d also inject an observation from Lucy Lippard, when she was writing about the controversies in the United States around the works of Andres Serano, Karen Finley and Robert Mapplethorpe: most – if not all – were driven by those defined – or deformed, if you will – by religion, and thus the body is always ‘bad’ and the only thing worse than that is a woman who makes work about the body. How little has changed, it seems.

But the work itself is at that intersection of horror and aesthetic evocation that we know from art history in the works of Francis Bacon or Francisco Goya. In other ways, this installation by Sterbak can be considered in tandem with Carolyn Wren’s War Map Dress Trilogy, that is a more subtle assertion of Barbara Kruger’s iconic work Untitled (Your body is a battleground).

I feel it’s also important to disclose that while writing this, I was also rewatching Todd Haynes film Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story that “portrays the last 17 years of singer Karen Carpenter’s life, as she struggled with anorexia.” (from here) This is also an artwork that had to deal with the travails of censorship…..

About the artist: “Jana Sterbak forges conceptual, architectonic objects that encourage their wearers to experience bodily and out-of-body freedom. Drawn to notions of doubling, physicality, and self-awareness, she favors juxtapositions between vanity and decomposition as a reminder of human vulnerability. This is evident in her dress of raw meat, which is meant to rest on a hanger until it rots and deteriorates. Such wearable, cage-like constructions allude to technological and societal constraints and a quest for freedom beyond corporeality. Sterbak’s art is marked by a dark humor and absurdist themes likely influenced by her childhood in Prague and education under Marxist and Leninist systems as well as the work of such writers as Franz Kafka and Jaroslav Hasek.” (from here)

More about Sterbak’s life and work can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Catherine Mellinger | Whips

March 17, 2023Catherine Mellinger | Whips

Originally from Saskatoon, mixed media collage artist Catherine Mellinger is a valued contributor to the Kitchener-Waterloo Region art scene. A graduate of the CREATE Institute in Toronto, Mellinger states that her work has always centered on her “own personal experience of being a human being.” While stating that she was originally shy and would not “blatantly state things” when it came to her work, Mellinger’s work developed after having children. As her life “exploded and imploded at the same time”, Mellinger explains how her art evolved as she “realized and connected to other feminist artists, other contemporary artists who were not having to hide. They were talking about trauma, mental illness and their personal lives as inspiration.” Today, Mellinger works with the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery and other community organizations and initiatives.

To read more click here.

Read More

Shelagh Howard

March 16, 2023Shelagh Howard | Paeonia Officinalis alba plena

“Genus/species” is a body of work that explores the invisible, all-encompassing power of names, labels, and language.

In 1735, Carl Linnaeus published “Systema Naturae”; his system for identifying and classifying the natural world, still in use today. Names have power.

To name something is to define it, to acknowledge its existence as unique and separate from any other thing. Language informs people whether they are safe and belong. Or not. Cruel words leave hurts in hidden places, removed from easy healing. Words can stigmatize those who are different, marginalize those who need uplifting, dehumanize populations whose needs are inconvenient to those in power.

In “Genus/species”, in lieu of their names or other descriptors of the model pictured, the images are identified by the taxonomic names of the flowers they hold, harkening back to botanical illustrations and Linnaean classification.

Without the backdrop of easy identifiers or assumptions, this work spotlights the exploration of concepts including, beauty, body image, intimacy, loneliness, vulnerability, isolation, and connection through the expression of human flesh.

Shelagh’s work with the male figure explores the rarely seen perspective of the male nude through a woman’s eyes—one that challenges traditional, toxic masculinity in favour of a viewing experience that is genuine, curious, human and humane.

This deliberate conceit in labeling by the artist forces the viewer to decouple easy assumptions from the earthly flesh on display. There are no quick judgements to be made; only questions that unfold in the liminal space between the seen and the unknown: Should the subjects be named or otherwise identified? Would doing so shift our perceptions? Is it our right and our role to cast their shadows into the light for our own comfort? A picture may be worth a thousand words—or a single name—but who is to say which words are right and true?

~ Rita Godlevskis

Read More

Shani Rhys James | Woman Smoking, 2011

March 7, 2023Shani Rhys James | Woman Smoking, 2011

“If painting doesn’t offer a way to dream and create emotions, then it’s not worth it.” (Pierre Soulages)

“Through the dialogue between paint and word, issues of domesticity, rootlessness and the relationship between women and the home will arise within the claustrophobic space, revealing how the places in which we live can say so much about who we are.” (Karen Price, from here)

There is a directness to James’ paintings – her moments that are both captured and created – of everyday, potentially ordinary scenes that is belied by her facility in paint. The physicality of the medium as employed by James’ is reminiscent of Lucian Freud (“She lathers and slathers on the paint with a kind of unrestrained glee” asserts Michael Glover), and the charged nature of what she presents to us is of the same ilk. Something has just happened, or is about to happen: there’s a quietus here, portentous and mildly unnerving.

The tight compositions of figures in rooms that seem suffocating were also a factor in the many works that James made about life during COVID lockdowns: “The claustrophobia of the interior is a metaphor for that frustration of being unable to express deep feelings of creativity, or to be involved in pertinent worldly issues.”

James also offers – not about this painting specifically, but applicable here that “my over-scaling of flowers [in the wallpaper] evokes either a cloying or menacing atmosphere, both repellent and seductive.” (from here)

Shani Rhys James is originally from Australia, but has lived and worked in Wales for since 1984. A more complete history can be read here.

If I may inject a touch of subjectivity, with the disclaimer that my mind often goes to dark places: when looking upon James’ people, I was reminded of an exchange in Margaret Laurence’s The Diviners, where the painter Dan McRaith finally shares some of his work with the main character Morag Dunn. McRaith figures, in the Gunn’s initial response, have ‘eyes [that] seem distanced, distorted–no, not distorted; the flesh mirrors the spirit’s pain, a greater pain than the flesh even if burned could feel. A grotesquerie of a woman, ragged plaid-shawled, eyes only unbelieving empty sockets, mouth open in a soundless cry that might never end, and in the background, a burning croft. Morag turns and looks at him, after looking at this last painting. “The dispossessed.”’

“Shani Rhys James is arguably the most exciting and successful Welsh painter of her generation. Her considerable reputation, both in Wales and beyond, continues to grow apace. She has exhibited with Martin Tinney Gallery since 1993 and subsequently her work has appeared in exhibitions throughout Britain and mainland Europe. William Packer, the distinguished art critic, has spoken of her as a painter of remarkable power, whose paintings are as convincing as anything currently being produced in Britain.” (from here, where you can see more of her fine works and learn about her many accomplishments)

Shani Rhys James’ site is here. She can be found on IG here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Dave Jordano | For Sale – America, Westside, Detroit, 2020, from his A Detroit Nocturne Series

March 2, 2023Dave Jordano | For Sale – America, Westside, Detroit, 2020, from his A Detroit Nocturne Series

In the West, the past is very close. In many places, it still believes it’s the present. (John Masters)

Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus | We hope for better things; it will arise from the ashes. (City of Detroit’s motto)

The city makes you; in a million little ways it makes you, and you can’t unmake yourself from it. (Craig Davidson, Cataract City)

Detroit is nothing if not a physical site of contested narratives: having lived in Windsor – Detroit for a half dozen years, the mythology and the reality of that city was something I was exposed to as I was just beginning to mature as an artist and writer, and that city (whether through the Detroit Institute of Arts or the stereotypes of the rust belt wonderlands, the legacy of the riots and so much malfeasance on the part of supposed stakeholders that layer ruin upon ruin) played a large part in my development. Eight Mile Road is not just a song by Eminem, but a real place, with real people, to me.

It’s unsurprising to find out that Jordano is from Detroit: his portraits of the city suggest an affection and an affinity that is more personal, and that he connects with his subjects – whether people or places – in a manner that is more gentle, despite the harshness of the locus he captures, often being abandoned, or the stark industrial lights that help define his scenes. Or perhaps it’s more like one of my favourite books about place and memory, where Craig Davidson talks about how “the most awful thing about living as an adult on the same streets where you grew up? It’s so easy to remember how perfect it was supposed to be. Reminders were always smacking you in the face. Good things happened—sure, I knew that. They just happened in other places.”

Jordano’s own words about this series are as follows: “I chose to make these images at night not only to put more emphasis on their surroundings, but also because I wanted to introduce a moment of quiet and calm reflection. These nighttime landscapes seem unfamiliar and therefore provoke contemplation. Pieces of the past, present, and future are rendered here to be carefully considered. They are, after all, the physical evidence of the city where we once carved our collective ambitions and lived out our dreams.”

I must inject more words – to augment or challenge Jordano’s own – from Craig Davidson’s Cataract City here: “Most of us in Cataract City were hard because the place built you that way. It asked you to follow a particular line and if you didn’t, well, you went and lived someplace else. But if you stayed, you lived hard, and when you died you went into the ground that way: hard.”

Much more of Jordano’s work can be enjoyed at his site as well as on Instagram.

His extensive body of work – under the title of A Detroit Nocturne – can be viewed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Recent Comments