In: art

Don Bonham | Twentieth Century Technology Utilized by Third World Mentality, 1993

September 9, 2022Don Bonham | Twentieth Century Technology Utilized by Third World Mentality, 1993

Don Bonham (1940 – 2014) was a sculptor who produced monumental works that intersect with classical ideas about art and also incorporated contemporary references – especially as pertains to industry and technology. His work alternates between humour and a disturbing – yet attractive – aesthetic that reflects back on a larger society, especially in terms of how often any new technological advance is met with the brutal inquiry of whether “Can this make killing less of a hassle?” (Sadly, the second blunt question is, “Can I have sex with it?”). If you think I’m wrong, consider other works by Bonham that would please J.G. Ballard as three dimensional iterations of some of Phoebe Gloeckner‘s illustrations to his texts…or horrify him, edit as you will.

Don’t criticize Bonham’s presumed priapism and the implicit male gaze in his work: an era gets the artwork it merits. His industrial works often openly acknowledged and built upon the fetishization of object that was a continuation of a fetishization of the female body. His works are always seductive and well executed, if initially unsettling.

In his own words: “The gap between human and machine is constantly shrinking. Are we to become more like machines, or machines more like us? The creators of technology have imbued machines with human characteristics, and this tendency is creating a more hospitable environment for their acceptance by society. As an artist I am only enlarging upon this concept.”

Years ago, a fine film critic spoke of how futurism, in cinema, was either a clean, antiseptic space, like an Apple store, or more like Blade Runner, and broken, dirty and more part of an industrial gothic aesthetic. Bonham falls within the latter.

I have been accused of being somewhat ‘subjective’ as a reviewer, often relying upon ‘inappropriate’ sources and considerations when engaging with artwork. This bemuses me, and entertains me even more when I consider that a motivation for featuring a work by Bonham is the rather disrespectful – though typical of the vagaries of institutions that claim to protect and nurture culture – decision by McIntosh Gallery, at the University of Western, to de accession one of his works from their collection. Curator, writer and gallerist Terry Graff has been working against that, and you can see his efforts – and learn more about Bonham and his legacy – at Graff’s social media.

But in looking at Bonham’s sculpture here (and many of his similar works that meld, merge and mash up humanity and machine, with a sense of militarism that is almost inappropriately amusing and intersects with black humour) a Vietnam era anti – war anthem from the 1960s comes to mind. This is fitting, as Bonham came to Canada during the period when many men from the United States were fleeing their country, opposed to the war there. However, “Bonham enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and served in an elite Recon unit in Southeast Asia. After six and a half years, he was honorably discharged to enter the University of Oklahoma as an Art History Major. He left university before graduating and worked in Detroit on a Ford assembly line before moving, in 1968, to London, Ontario, where he discovered a dynamic arts community that reinforced his decision to pursue a career as a visual artist.” (from a retrospective of Bonham’s artwork at The Beaverbrook Art Gallery)

The song Sky Pilot by The Animals is as confrontational as Bonham’s Twentieth Century Technology Utilized by Third World Mentality, and for its time was surely controversial: and it’s necessary to include the print below that Bonham produced, of his modified – or realized – helicopters swooping down, mimicking that infamous scene where the ‘righteous’ decimate a village from Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Death rides a pale horse, a mechanized cyborg that’s surely a descendant of Albert Pinkham Ryder’s The Race Track (Death on a Pale Horse), coming down from the sky….

Regionalism has both defined – and deformed – Canadian art and Canadian art history (and is arguably why Bonham’s work is being so disrespected by the University of Western. Graff is more erudite and informed on this front than I). But regionalism is also the lens through which I respond to the terms of ‘First World’ or ‘Third World’ (cited in the title of this work) which seem as archaic at times as ‘Cold War’ (an epoch I had to explain to students, when I used to teach at a university, and let’s remember that the ‘Second World’ was the Communist Bloc, and the most avowed communist country now is definitely ‘open for business’…).

Bluntly, there are those who have and those who have not, and the tools at hand are used to enhance the former and demean the latter: it is the ‘order of things’, in the era of late capitalist modernism (to quote Jameson) or, as I like to call it, late modernist capitalism. Trinh T. Minh-ha (a Vietnamese – so she has an intimate understanding of the construction of history, as pertains to colonization / imperialism – filmmaker, writer, literary theorist, composer, and professor) famously wrote that “there is a third world in every first world, and vice-versa.” Bonham – and myself, initially – spoke of Vietnam. But you’re more likely to see a third world in your own city, overseen and monitored by a machine not unlike this sculpture (with the excessive militarization of police departments), in the skies over Detroit or Cleveland or Baltimore…or my own site of Niagara, or my previous space of Saskatoon, with tent cities and other ‘undesirables’, too often given harm over help, unlike other more harmful groups that squat, rife with sedition and fascist symbols….

Many thanks to Terry Graff for support, and conversations, that helped define this essay. Much more about Bonham’s life and artwork can be seen at Graff’s social media feed (there is also a petition to make Western reverse their decision here) and Bonham was a past Artist You Need To Know, in AIH Studios’ ongoing series. That can be enjoyed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

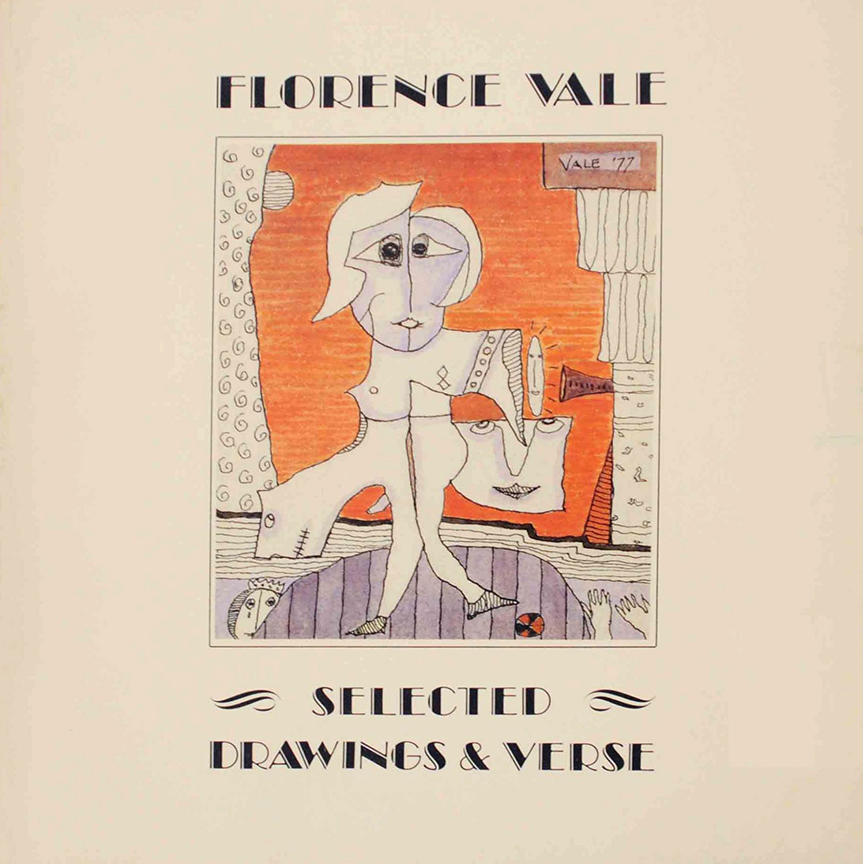

Florence Vale | Selected Drawings & Verse, 1979

November 3, 2022Florence Vale | Selected Drawings & Verse, 1979

Published by Aya Press, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 1979

My love created

something more real than you are

how disappointing

Florence Vale was an artist influenced equally by surrealism, expressionism and cubism, melding these sometimes disparate movements into unique works. “I paint what I dream,” Florence Vale (1909 – 2003) stated, and the late art historian Natalie Luckyj offered that “Her art was a world in which fantasy and reality are interwoven to create a private and secret environment.”

She published several books of her writing intermixed with her artwork: in this slim volume, the drawings are linear and simple, and often erotic. The text alternates between a light-hearted salaciousness and more stark, desolate meditations upon love.

Vale was a previously featured artist in AIH Studios’ ongoing series of Artists You Need To Know. That can be enjoyed here, where you can see more of her artwork.

A light went out

and I can’t turn it on

the dark is frightening

engulfing

temptation is rife

a momentary relief

leaving regrets

and the pain is there still

but deeper now

despair strains the heart

longing is agony

God’s love cannot compensate for yours

This is not an easy book to find, though you may be able to procure it online through spaces like this one. But – as I so often do – I would suggest your local library, or a local second hand book store, as they have been – and continue to be – treasure troves of fine art books. I discovered this book in the library at AIH Studios, but also have a copy of another of Vale’s publications of prose and pictures that I bought at an artist run centre’s ‘yard sale.’

I must also inject that there are too few collections of artists’ books and publications that are accessible to all, in gallery and museum spaces, and this is an unfortunate consequence of the prevalence of digital spheres, now….

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

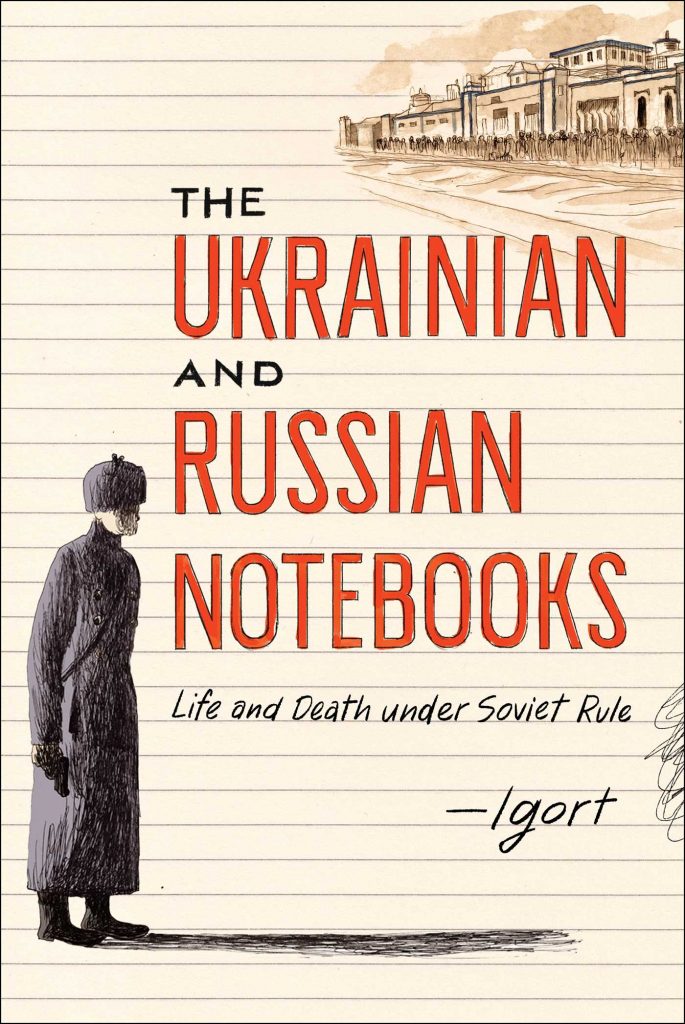

The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule | Igort, 2016

September 1, 2022The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule | Igort, 2016

All has been looted, betrayed, sold; black death’s wing flashed ahead.

(Anna Akhmatova)

Of late, I’ve been exploring more graphic novels in my reading (this was partly inspired by Virgil Hammock’s feature on Jon Claytor’s Take The Long Way Home). I cut my artistic teeth on comics, as a teenager, and it’s been good to see them garnering the respect they merit in North American cultural discourse.

Sometimes I’ll pick things up at random. That’s how I encountered Putain de Guerre! (Goddamn This War!), by Jacques Tardi and Jean-Pierre Verney, translated into English by Helge Dascher. That graphic novel came to mind as I was reading – also having picked it up on a whim – The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule, by Cuadernos de Igort (who creates his work under the name Igort) with Jamie Richards as translator.

Both are horrific. Putain de Guerre! is perhaps less shockingly immediately visceral, as we can pretend it’s more remote, more ‘done’ and ‘in the past.’ But Igort’s Notebooks have a contemporary resonance, with what’s happening in the Ukraine right now. It scalds, in an immediate manner, and you’ll carry the personal stories of the people in it with you, long after you’ve put it down. It horrifies, and the personal narratives splash onto, and into, you, if you even have the barest sense of empathy. In this sense, it’s like Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, where myself – and everyone I know who’s read it – found they had to repeatedly check the endnotes, as the sheer numbers of slaughter and death seemed unreal. A friend from Poland told me she could only read it in parts, as it was simply too much.

The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule are equally harrowing, as brilliant in a minimalist artistic execution as they are grotesquely overwhelming in the tales being related.

“After spending two years in Ukraine and Russia, collecting the stories of the survivors and witnesses to Soviet rule, masterful Italian graphic novelist Igort was compelled to illuminate two shadowy moments in recent history: the Ukraine famine and the assassination of a Russian journalist. Now he brings those stories to new life with in-depth reporting and deep compassion.

In The Russian Notebooks, Igort investigates the murder of award-winning journalist and human rights activist Anna Politkoyskaya. Anna spoke out frequently against the Second Chechen War, criticizing Vladimir Putin. For her work, she was detained, poisoned, and ultimately murdered. Igort follows in her tracks, detailing Anna’s assassination and the stories of abuse, murder, abduction, and torture that Russia was so desperate to censor. In The Ukrainian Notebooks, Igort reaches further back in history and illustrates the events of the 1932 Holodomor. Little known outside of the Ukraine, the Holodomor was a government-sanctioned famine, a peacetime atrocity during Stalin’s rule that killed anywhere from 1.8 to twelve million ethnic Ukrainians. Told through interviews with the people who lived through it, Igort paints a harrowing picture of hunger and cruelty under Soviet rule.”

“With elegant brush strokes and a stark color palette, Igort has transcribed the words and emotions of his subjects, revealing their intelligence, humanity, and honesty—and exposing the secret world of the former USSR.” (This quote, and the previous one, are from here).

If – after all that – you’re still interested to seek out a copy of Igort’s recording of the stories of Serafima Andreyevana, Nikolay Vasilievich, Maria Ivanovna and so many others, I suggest visiting the artist’s site, though my local library has an impressive collection of graphic novels and their ilk, and that’s a fine place to begin, as well.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Ema Shin | Hearts of Absent Women

August 26, 2022Ema Shin | Hearts of Absent Women

…as empty as an unremembered heart.

(Mervyn Peake, from his Gormenghast Trilogy)

I was born in Japan and grew up in a traditional Korean Family. My grandfather kept a treasured family tree book for 32 generations, but it only included male descendants’ names, not daughters. In my art, I have always tried to celebrate women and their historical handcrafts. These sculptural hearts are made from embroidery, handwoven tapestry, and papier mâché to recognize and celebrate the silent behind-the-scenes domestic duties of women and represent not only her emotions but serve as offerings or amulets for her protection.

(Ema Shin’s words, from here)

Of late, I’ve been watching the series Motherland: Fort Salem. I’ve a weakness – if you wish to put it that way, but I prefer affinity – for science fiction and fantasy (something I’ve been told, along with my interest in horror, is ‘inappropriate’ for an arts journalist…you know, like how the ‘only real art is painting’, ahem, to cite some of the karaoke modernists I endured on the prairies). The ‘alternate worlds’ are what interest me. When I was consuming William Gibson’s books, I was always more fascinated by the subtle things in his stories, presented as more factual and less chimeric (that the USSR eventually – for all intents and purposes – is run by the ‘criminal’ Kombinant, with the Russian mafia having fully taken over the government, that a religious cult appears that believes god speaks to them through movies – only from a certain era, of course – or that another character makes a living testing logos and brands, as she has an immediate, allergic reaction to any kind of advertising…)

In Motherland, a different world exists than that which we occupy: one where the Salem Accords have forged an uneasy alliance between the Witches of Salem and the United States Government, playing out in contemporary times. Imagine a military industrial complex based upon the magic of witches (or more accurately, the power of women), and – this is the part that is of more interest to me – a society that has formed around that, marking a genesis even before the United States became the United States, that is very matriarchal. Small things stood out to me, about how social ‘norms’ and customs play out very differently in this ‘world’ than in our own, especially around sexuality, power, who is expected to lead and who is expected to follow, and how history – in Salem – is overtly defined by a female gaze, if you will. I say ‘overtly’, as I always remember Martha Langford’s Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums, and those outside the frame who define it, but still are unseen metaphorically as well as literally…..

Ema Shin is a Melbourne based artist who was born and grew up in Niigata, Japan: she studied traditional and contemporary Japanese printmaking in Tokyo and completed a Master of Fine Art Degree in Nagoya. Shin has exhibited widely in Japan, Korea, Australia and elsewhere. Prior to this series, Shin focused on a variety of printmaking techniques and mediums, including Japanese woodblock printing, papier-mâché, embroidery, book making, Urauchi (chine-colle) and collage.

This interest in the physicality of materials continued when, due to motherhood and the pandemic, Shin “began to explore tapestry and embroidery…her red embroidered organs and [three dimensional] human hearts are beautiful to look at, and deeply personal-political in meaning.” (from here)

These are the archival giclée prints of the delicate objects Shin has created as part of her Hearts of Absent Women series (all photographs are by Matthew Stanton), and are an edition of 50.

From her site (which has many of her other fine works, so I encourage you to explore it): “Shin aims to create compositions that express sensitivity for tactile materials, the contemporary application of historical techniques, physical awareness, femininity and sexuality to celebrate women’s lives and bodies.”

Her Instagram is @ema.shin.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Menashe Kadisman | Shalechet (Fallen Leaves), 1997 – 2001

August 19, 2022Menashe Kadishman | Shalechet (Fallen Leaves), 1997 – 2001

Installation, Jewish Museum, Berlin

When we were young, we wanted our art to change the world. But when Hitler bombed Guernica, did Picasso’s painting have any effect? I thought that maybe some things of mine could do good. My sculptures didn’t change the war in Lebanon. Maybe art is not about changing anything. It’s about telling you reality. (Menashe Kadishman)

I will admit that I rely upon the term ‘contested narratives’ a bit too much: but when confronted with Kadishman’s installation, where his own personal history (as the child of two committed Zionists, in the early twentieth century) and larger tropes intersect, contradict and in some ways twist and transform in a manner that is more apropos to a fictional story than our expectations of ‘reality’, I feel I have no recourse.

Kadishman’s installation is “primarily associated with the Shoah (the Holocaust) [but] it holds a universal message against violence and human suffering. Kadishman himself notes that the work can relate to different tragedies such as World War I and Hiroshima. In part, Shalechet derives its meaning from the context of its presentation. For example, it took on a new meaning in 2018, when it was exhibited at the Memorial Hall dedicated to the victims of the Nanjing massacre in China.” (I include a link as this horror is lesser known, in the cacophony of savagery that is human history, like the many – repetitive, interchangeable, eternal – ‘faces’ silently wailing on the floor of Shalechet, growing old and rusting and still unheard….)

Read more of Gazzola’s response to this work here.

Read More

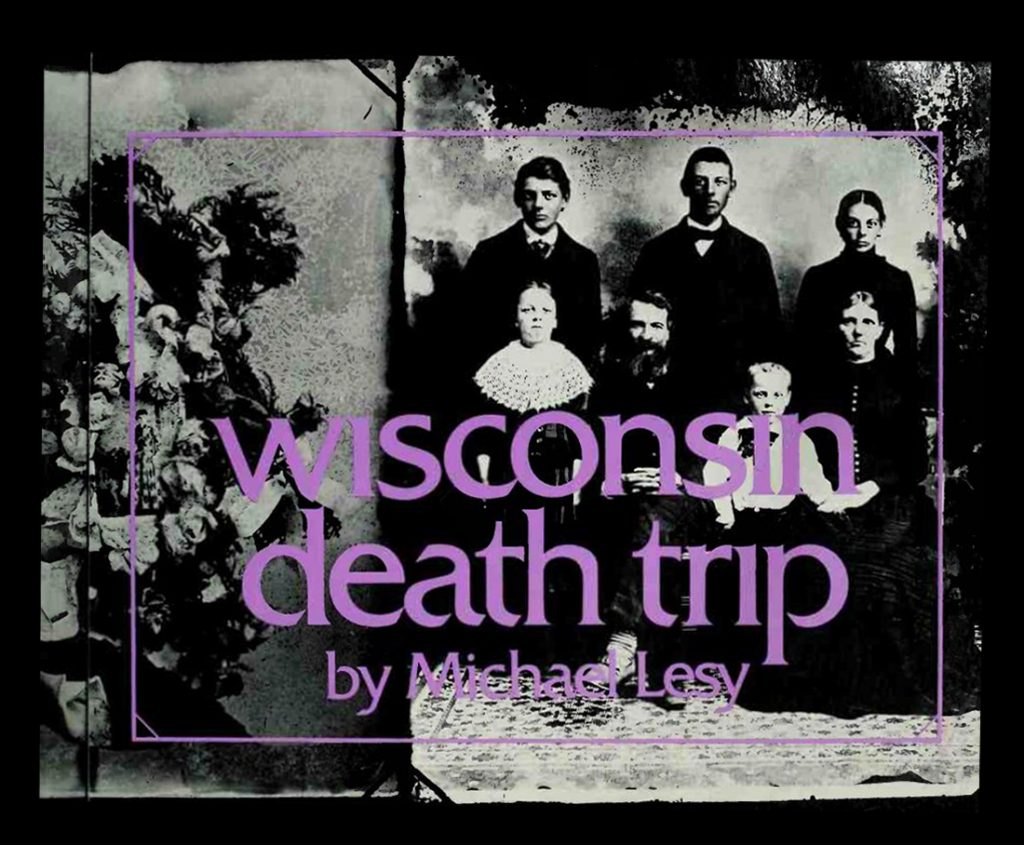

Wisconsin Death Trip | Michael Lesy, 1973

August 11, 2022Wisconsin Death Trip | Michael Lesy, 1973 (reprinted in 1991 by Anchor Books, and University of New Mexico Press in 2000)

Pause now. Draw back from it. There will be time again to experience and remember. For a minute, wait, and then set your mind to consider a different set of circumstances: consider those scholars and social philosophers who never knew that Anna Myinek had burned her employer’s barn or that Ada Arlington had shot her lover, but who nevertheless understood that something strange and extraordinary was happening in the middle of the continent at nearly the same instant that they sat in their studies, surrounded by their books. Such men did their best to understand what it meant, and in the process they tried to predict that future in which we are now enmeshed.

The only problem is how to change a portrait back into a person and how to change a sentence back into an event….The thing to worry about is meanings, not appearances.

I first became aware of Wisconsin Death Trip – the book by Michael Lesy and the James Marsh film it inspired, which I’m less impressed with – while reading Stephen King’s novella 1922, as King has mentioned it as inspiration. It’s one of those King stories that could be interpreted as flirting with the supernatural, but may, in fact, simply be everyday horror. 1922 tells the tale of an ignorant, greedy man on a failing, hardscrabble farm, who murders his wife and thus brings about the death of his beloved son (the ‘ghost’ of his wife returns, Banquo – like, to tell of this before his child’s body is even found). He survives only to suffer and regret, losing all he owned – and his hand, to infection – and is haunted, for years, by the rats that consumed his murdered wife’s body, that only he can hear, and suffers their chittering call and bites in the long dark nights until he takes his own life to escape….

Read more of Gazzola’s thoughts about Wisconsin Death Trip here.

Read More

Philip Monk | Is Toronto Burning?: Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Community

July 7, 2022Philip Monk, Is Toronto Burning?: Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene, London: Black Dog Publishing, 2016.

Jack Pollock, Dear M: Letters from a Gentleman of Excess, McClelland & Stewart, 1989

“Each day I write. I’m not sure what it’s all about, but most days I write about art and the constant raping of its values by pseudo intellectual acrobats.” (Jack Pollock, Dear M: Letters from a Gentleman of Excess)

Nothing seems more improbable than what people believed when this belief has gone with the wind. (Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook)

“Culture has replaced brutality as a means of maintaining the status quo.” (Philip Monk, Is Toronto Burning? Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene)

A spate of old issues of FILE magazine came into my hands over the past year (it’s worth noting that they were a gift from Elizabeth Chitty, who also gave me the copy of Monk’s book that spurred this essay). They’re a bit ragged, but that seems appropriate, as they’re like flashbacks (the magazine began publishing in 1972 and ran for 17 years, with 26 issues) that don’t resonate with many, more nostalgia than substance.

They seem very dated, at times very juvenile, and more of an exercise in artistic onanism than anything else. This is, of course, a generalization, and it’s broken in certain points quite clearly. The issue that is almost entirely colour images of the three poodles, one of the many symbolic personas of General Idea, engaged in various tumbling and enthusiastic sex acts is one to keep (as I was impressed when I saw one of the large paintings from this series on a trip to the Art Gallery of Hamilton, installed amidst other notable Canadian works from Graham Coughtry to Attila Lukacs).

But many of the other copies of FILE are easily dismissed, even by someone like myself who has made a career of excavating in spaces that are too often ignored as pertains to Canadian Art history. The odd flash of brilliance, or the appropriation of mainstream media narratives and iconography, the sampling of authors from Burroughs to Acker, are the exception, not the rule.

Perhaps, this many decades later, our expectations of how artists engage in appropriation is more sophisticated – or more jaded. Edit as you will.

But all this reminded me of my long overdue response to Philip Monk’s book Is Toronto Burning? Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene), published several years ago, and that is focused upon the same era. I found the book uneven, and some players and characters in this story seem somewhat incongruous to their later roles or personas (true or assigned, in that vague way of art history and cultural narratives). But Monk’s own words lead to this: “In a sense, what follows is a story, a story with a cast of characters. These characters are pictured in video, photography, and print – not necessarily as portraits but rather as performers.” (from the chapter 1977). But in finally offering my impression of Monk’s narrative (considering personal and public factors and all the sites where those contested narratives collude and collide), I’ll begin with the following assertion: “All narrators are unreliable. Especially when they are characters within their own story.”

Read more here.

Read More

The Death of the Artist | William Deresiewicz, 2020

June 3, 2022The Death of the Artist: How Creators Are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech | William Deresiewicz, 2020

I cannot think of another field in which people feel guilty about being paid for their work—and even guiltier for wanting to be.

This is – bluntly – a difficult book. It was necessary for me to read it in installments, and I know that many of my friends who are artists had to do the same. Perhaps it was like a series of inoculations against a disease, spaced out to have maximum curative effect. It motivated me to revisit Robert Hughes’ essay Art and Money, from his book Nothing If Not Critical, and simultaneously I was reading Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code by Primavera De Filippi and Aaron Wright (as part of my ongoing attempt to understand the phenomenon of NFTs better). Three decades separate those two books, and they make an interesting extended bibliography to The Death of the Artist. Sometimes there’s concurrences, more often disagreement, and a feeling that more time must have passed between their publication, as the gulf is so wide that Doris Lessing’s idea that ‘nothing seems more improbable than what people believed when this belief has gone with the wind’ floated in the air, as I read.

For anyone who’s worked in culture, or has attended art school or various other educational institutions focused upon producing ‘creators’, there are numerous assertions made in William Deresiewicz’ book that will ring true, in a rueful manner that many of us may have denied (or sadly, will continue to do so, unto the pauper’s grave). Some of the stories from the artists – of various stripes – that Deresiewicz spoke with, that inform this book, will be very familiar. My own experience in public galleries or artist run centres, and attempting to negotiate being a cultural worker in other spheres, match the stories here.

This book might offend you, but it will offend you in all the correct ways, and perhaps offend all the appropriate people.

If art is work, then artists are workers. No one likes to hear this. Nonartists don’t, because it shatters their romantic ideas about the creative life. Artists don’t either, as people who have tried to organize them as workers have told me. They also buy into the myths; they also want to think they’re special. To be a worker is to be like everybody else. Yet to accept that art is work—in the specific sense that it deserves remuneration—can be a crucial act of self-empowerment, as well as self-definition.

A tangent, not unrelated, if I may, that aligns with Deresiewicz’ research: a friend is an artist, exhibiting widely, and has been teaching as a sessional for several years. She is me, twenty years ago: she has less protection, security and opportunity than I did, despite both of us doing ‘all the right things.’ We are – like many workers – in a steady decline, that seems not only unstoppable, but unrecognized. Another gem from Deresiewicz’ book: The writer and visual artist Molly Crabapple, another exemplary leftist, puts it like this in her essay “Filthy Lucre”: “Not talking about money is a tool of class war.”

Art is hard. It never just comes to you. The idea of effortless inspiration is another romantic myth. For amateurs, making art may be a form of recreation, but no one, amateur or professional, who has tried to do it with any degree of seriousness is under the illusion that it’s easy. “A writer,” said Thomas Mann, “is someone for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.” More difficult, because there is more for you to do, more that you know how to do, and because you hold yourself to higher standards.

If I ever dared to revisit academic or educational spaces – or if I was let back in – this text would be required reading, not just for those wanting to become artists, but especially for those who would go on to be gallerists, cultural workers and even players within the political sphere, as in some ways this book is a warning. But there’s a large dollop of Cassandra in cultural spaces, especially in Canada (several years ago, I was pilloried for shaming an artist run centre for not paying emerging artists, but the abuse was worth it as they – eventually – did the right thing). Deresiewicz’ research, and the testimonials in this book, can help break that complacency….

The Death of the Artist: How Creators Are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech is not so much a warning, as a reality. It is a severe, but indispensable, book.

All quotes in italics are from Deresiewicz’ book. As usual, I suggest visiting a local bookstore (such as Someday Books) to pick up this text.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Essay – Ron Hewson – Community Galleries

March 1, 2022Community Galleries

I’ve been putting a lot time and effort lately into a community gallery that I belong to. While doing this I’ve put some thought into why I feel it’s worth the effort. Here are some of my reasons to to belong to and participating in this endeavour.

I believe it’s important for local artists to have a place to hang their work. Putting my work on a wall in a public space means I feel that I have created something that is worthy of public display. This matters because the emotional investment in producing art needs that outlet. Showing in a gallery is the reward for the time and money put into our work. I know I would continue to work regardless of belonging to a gallery but knowing that I can share what I have made is incentive to keep working.

Belonging to the gallery means I have to finish things. Every couple months I need new framed finished work to display. As a photographer I can capture a vast number of images. However that really doesn’t mean anything if I don’t finish any of them. Sure I can do some quick editing and post them on Instagram or do some more careful work and post on a stock photo site but that’s not the same as taking the extra steps to print and frame something. The incentive to finish work is a big benefit of belonging to the gallery.

Preparing work for the community gallery on a regular basis is far less stressful that preparing for a major gallery show. I’ve done shows at “big” galleries. The thrill and sense of accomplishment that comes from that kind of show can’t be beat. But the investment in time and money can be overwhelming. Its not something that everyone is prepared to do or is willing to do and for most people its out of reach. The community gallery fills that need perfectly. It gives the opportunity to exhibit that is manageable for artists who want to exhibit without the stress of a solo show.

There are many other reason the gallery is worth my time such as the diversity of the art on display and the camaraderie of follow artists but what makes to gallery valuable to me is the incentive to keep working. I believe that everyone needs some form of incentive and that for me is to have my photography physically present in the world. While posting something online might get seen by lots of people we don’t paint or sculpt or create our art to be seen on a phone.

Visit uptowngallerywaterloo.com

~ Ron Hewson

Read More

Diana Nicholette Jeon

November 11, 2021Diana Nicholette Jeon is a Hawai’i based photographer whose works have been widely published and exhibited, including (coincidentally) by The COVERT Collective’s Peppa Martin. Diana’s photos have won awards at the Julia Margaret Cameron Awards, the Moscow Foto Awards and the Pollux Awards to name a few.

“Untitled (from the series, 860 Days)” is a photo that immediately conveys a sense of solitude. The extreme blurring of part of the image takes it a step further to impart an unwanted sense of loneliness, and of not knowing how to escape it… like a bad dream. In fact, the series itself (here) is “about my experience of loss, isolation, anguish and loneliness during a marital separation.”

Jeon’s other projects are equally as personal and introspective, and often combine selfies with other photographic elements to create unique pastiches that engage the viewer to try to connect with the psyche of Jeon herself… what is she feeling here? … why did she choose this? While all art seeks to create this bond with its audience, Jeon’s work is extraordinarily successful at it.

You can see more of Diana’s work at her website, including the series Self-Exposure, Socially Speaking, Nights as Inexorable as the Sea and I, Orfeo.

https://diananicholettejeon.com/

~ Mark Walton

Read More

Recent Comments