In: curated

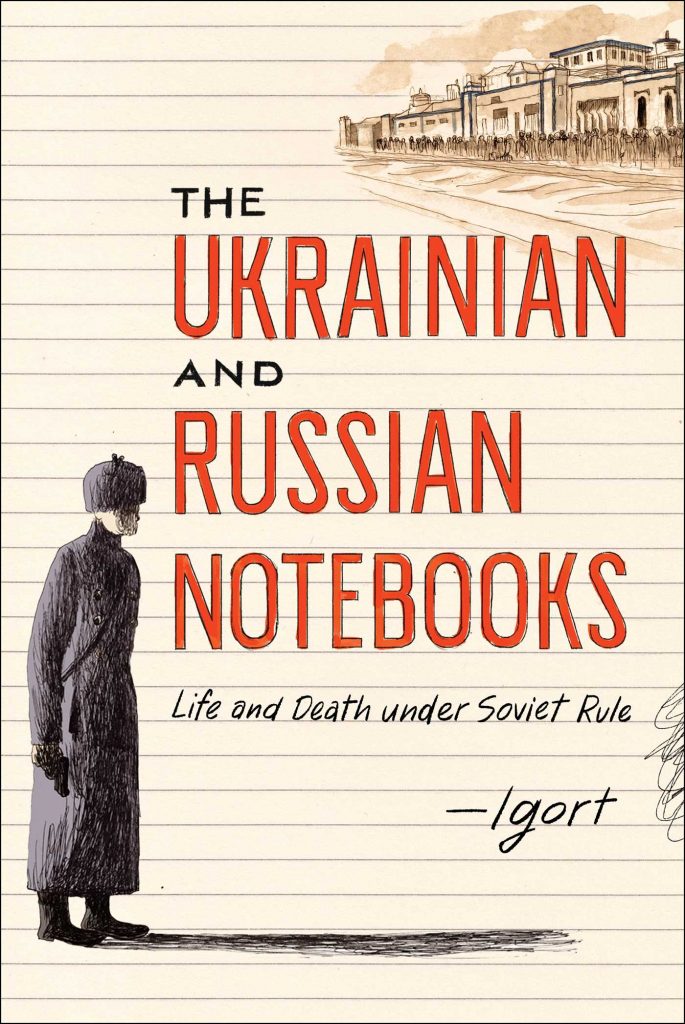

The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule | Igort, 2016

September 1, 2022The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule | Igort, 2016

All has been looted, betrayed, sold; black death’s wing flashed ahead.

(Anna Akhmatova)

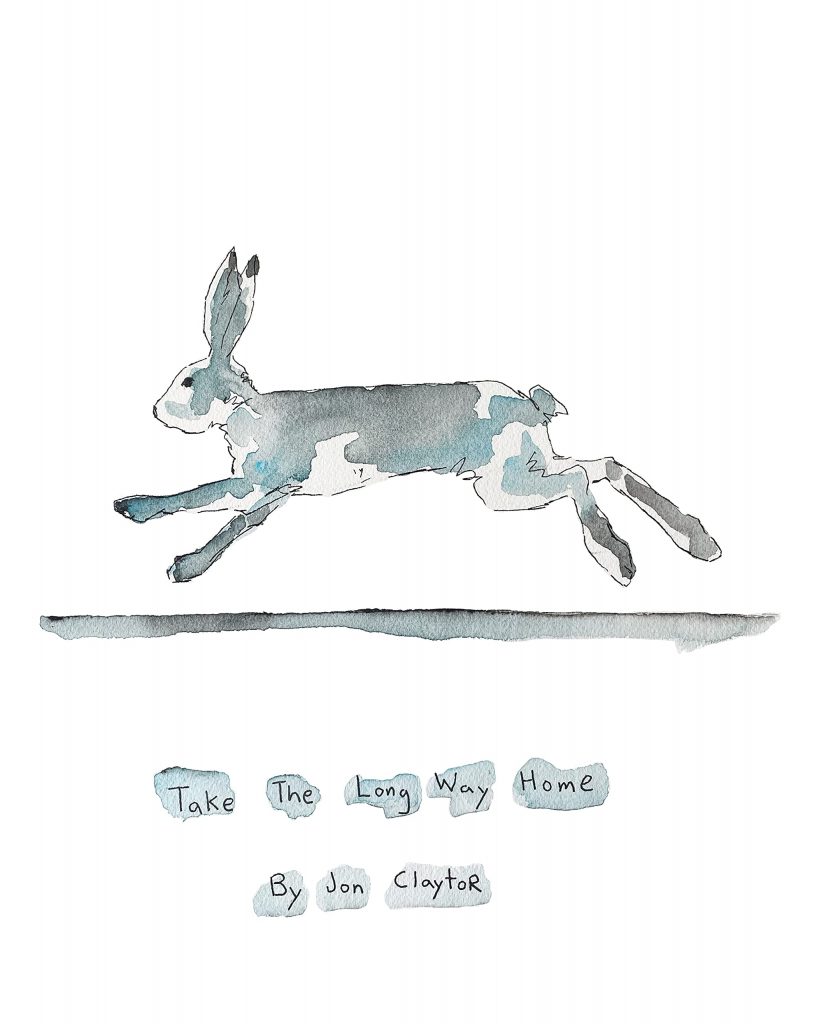

Of late, I’ve been exploring more graphic novels in my reading (this was partly inspired by Virgil Hammock’s feature on Jon Claytor’s Take The Long Way Home). I cut my artistic teeth on comics, as a teenager, and it’s been good to see them garnering the respect they merit in North American cultural discourse.

Sometimes I’ll pick things up at random. That’s how I encountered Putain de Guerre! (Goddamn This War!), by Jacques Tardi and Jean-Pierre Verney, translated into English by Helge Dascher. That graphic novel came to mind as I was reading – also having picked it up on a whim – The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule, by Cuadernos de Igort (who creates his work under the name Igort) with Jamie Richards as translator.

Both are horrific. Putain de Guerre! is perhaps less shockingly immediately visceral, as we can pretend it’s more remote, more ‘done’ and ‘in the past.’ But Igort’s Notebooks have a contemporary resonance, with what’s happening in the Ukraine right now. It scalds, in an immediate manner, and you’ll carry the personal stories of the people in it with you, long after you’ve put it down. It horrifies, and the personal narratives splash onto, and into, you, if you even have the barest sense of empathy. In this sense, it’s like Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, where myself – and everyone I know who’s read it – found they had to repeatedly check the endnotes, as the sheer numbers of slaughter and death seemed unreal. A friend from Poland told me she could only read it in parts, as it was simply too much.

The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule are equally harrowing, as brilliant in a minimalist artistic execution as they are grotesquely overwhelming in the tales being related.

“After spending two years in Ukraine and Russia, collecting the stories of the survivors and witnesses to Soviet rule, masterful Italian graphic novelist Igort was compelled to illuminate two shadowy moments in recent history: the Ukraine famine and the assassination of a Russian journalist. Now he brings those stories to new life with in-depth reporting and deep compassion.

In The Russian Notebooks, Igort investigates the murder of award-winning journalist and human rights activist Anna Politkoyskaya. Anna spoke out frequently against the Second Chechen War, criticizing Vladimir Putin. For her work, she was detained, poisoned, and ultimately murdered. Igort follows in her tracks, detailing Anna’s assassination and the stories of abuse, murder, abduction, and torture that Russia was so desperate to censor. In The Ukrainian Notebooks, Igort reaches further back in history and illustrates the events of the 1932 Holodomor. Little known outside of the Ukraine, the Holodomor was a government-sanctioned famine, a peacetime atrocity during Stalin’s rule that killed anywhere from 1.8 to twelve million ethnic Ukrainians. Told through interviews with the people who lived through it, Igort paints a harrowing picture of hunger and cruelty under Soviet rule.”

“With elegant brush strokes and a stark color palette, Igort has transcribed the words and emotions of his subjects, revealing their intelligence, humanity, and honesty—and exposing the secret world of the former USSR.” (This quote, and the previous one, are from here).

If – after all that – you’re still interested to seek out a copy of Igort’s recording of the stories of Serafima Andreyevana, Nikolay Vasilievich, Maria Ivanovna and so many others, I suggest visiting the artist’s site, though my local library has an impressive collection of graphic novels and their ilk, and that’s a fine place to begin, as well.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Ema Shin | Hearts of Absent Women

August 26, 2022Ema Shin | Hearts of Absent Women

…as empty as an unremembered heart.

(Mervyn Peake, from his Gormenghast Trilogy)

I was born in Japan and grew up in a traditional Korean Family. My grandfather kept a treasured family tree book for 32 generations, but it only included male descendants’ names, not daughters. In my art, I have always tried to celebrate women and their historical handcrafts. These sculptural hearts are made from embroidery, handwoven tapestry, and papier mâché to recognize and celebrate the silent behind-the-scenes domestic duties of women and represent not only her emotions but serve as offerings or amulets for her protection.

(Ema Shin’s words, from here)

Of late, I’ve been watching the series Motherland: Fort Salem. I’ve a weakness – if you wish to put it that way, but I prefer affinity – for science fiction and fantasy (something I’ve been told, along with my interest in horror, is ‘inappropriate’ for an arts journalist…you know, like how the ‘only real art is painting’, ahem, to cite some of the karaoke modernists I endured on the prairies). The ‘alternate worlds’ are what interest me. When I was consuming William Gibson’s books, I was always more fascinated by the subtle things in his stories, presented as more factual and less chimeric (that the USSR eventually – for all intents and purposes – is run by the ‘criminal’ Kombinant, with the Russian mafia having fully taken over the government, that a religious cult appears that believes god speaks to them through movies – only from a certain era, of course – or that another character makes a living testing logos and brands, as she has an immediate, allergic reaction to any kind of advertising…)

In Motherland, a different world exists than that which we occupy: one where the Salem Accords have forged an uneasy alliance between the Witches of Salem and the United States Government, playing out in contemporary times. Imagine a military industrial complex based upon the magic of witches (or more accurately, the power of women), and – this is the part that is of more interest to me – a society that has formed around that, marking a genesis even before the United States became the United States, that is very matriarchal. Small things stood out to me, about how social ‘norms’ and customs play out very differently in this ‘world’ than in our own, especially around sexuality, power, who is expected to lead and who is expected to follow, and how history – in Salem – is overtly defined by a female gaze, if you will. I say ‘overtly’, as I always remember Martha Langford’s Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums, and those outside the frame who define it, but still are unseen metaphorically as well as literally…..

Ema Shin is a Melbourne based artist who was born and grew up in Niigata, Japan: she studied traditional and contemporary Japanese printmaking in Tokyo and completed a Master of Fine Art Degree in Nagoya. Shin has exhibited widely in Japan, Korea, Australia and elsewhere. Prior to this series, Shin focused on a variety of printmaking techniques and mediums, including Japanese woodblock printing, papier-mâché, embroidery, book making, Urauchi (chine-colle) and collage.

This interest in the physicality of materials continued when, due to motherhood and the pandemic, Shin “began to explore tapestry and embroidery…her red embroidered organs and [three dimensional] human hearts are beautiful to look at, and deeply personal-political in meaning.” (from here)

These are the archival giclée prints of the delicate objects Shin has created as part of her Hearts of Absent Women series (all photographs are by Matthew Stanton), and are an edition of 50.

From her site (which has many of her other fine works, so I encourage you to explore it): “Shin aims to create compositions that express sensitivity for tactile materials, the contemporary application of historical techniques, physical awareness, femininity and sexuality to celebrate women’s lives and bodies.”

Her Instagram is @ema.shin.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Menashe Kadisman | Shalechet (Fallen Leaves), 1997 – 2001

August 19, 2022Menashe Kadishman | Shalechet (Fallen Leaves), 1997 – 2001

Installation, Jewish Museum, Berlin

When we were young, we wanted our art to change the world. But when Hitler bombed Guernica, did Picasso’s painting have any effect? I thought that maybe some things of mine could do good. My sculptures didn’t change the war in Lebanon. Maybe art is not about changing anything. It’s about telling you reality. (Menashe Kadishman)

I will admit that I rely upon the term ‘contested narratives’ a bit too much: but when confronted with Kadishman’s installation, where his own personal history (as the child of two committed Zionists, in the early twentieth century) and larger tropes intersect, contradict and in some ways twist and transform in a manner that is more apropos to a fictional story than our expectations of ‘reality’, I feel I have no recourse.

Kadishman’s installation is “primarily associated with the Shoah (the Holocaust) [but] it holds a universal message against violence and human suffering. Kadishman himself notes that the work can relate to different tragedies such as World War I and Hiroshima. In part, Shalechet derives its meaning from the context of its presentation. For example, it took on a new meaning in 2018, when it was exhibited at the Memorial Hall dedicated to the victims of the Nanjing massacre in China.” (I include a link as this horror is lesser known, in the cacophony of savagery that is human history, like the many – repetitive, interchangeable, eternal – ‘faces’ silently wailing on the floor of Shalechet, growing old and rusting and still unheard….)

Read more of Gazzola’s response to this work here.

Read More

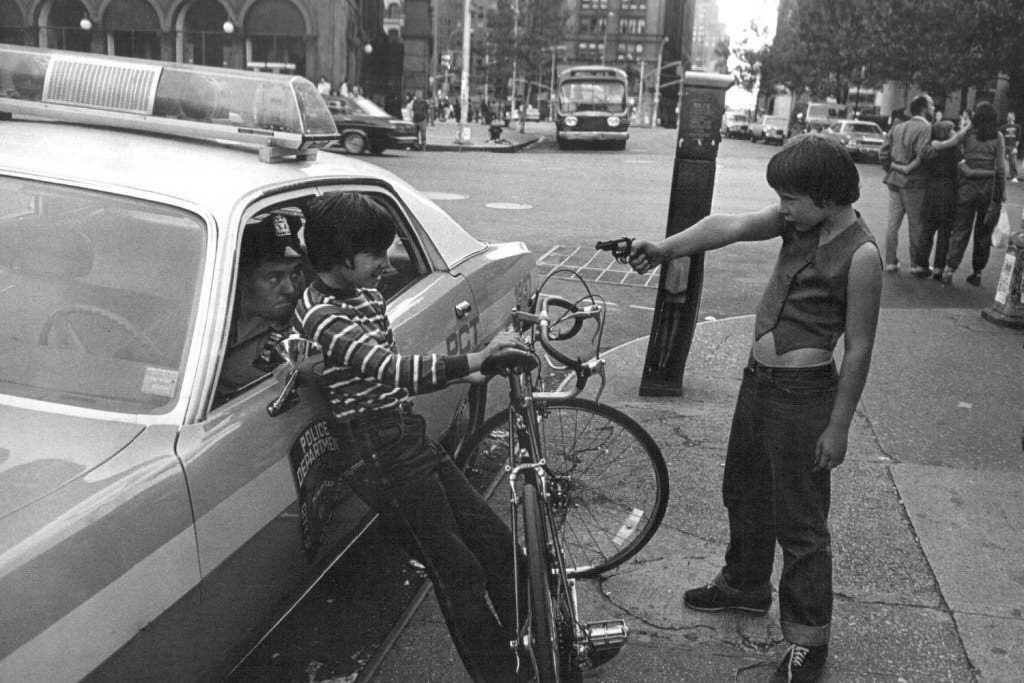

Gun Play | Jill Freedman

August 8, 2022Jill Freedman is a name you should know in the world of photography… but more than likely don’t. With a career that spanned 40 years, 7 (and counting) books and pieces acquired by major galleries, Freedman’s work connects deeply with her subjects in a manner unlike most documentary photographers.

From the very beginning, Jill was IN. She didn’t go to take photos of Resurrection City in Washington in 1968; she LIVED in the camp with the protesters for the duration of that campaign. She travelled with the circus for several months in the early 70’s to get her incredible photos of life under and around the big top. She embedded herself in the firehouses and police precincts of NYC and came out with work so beautiful and intimate that her two books on the subjects (Firehouse and Street Cops) were snapped up by first responders when they were re-released in the early 2000’s.

When Pulitzer Prize winner Studs Terkel wrote his oral history Working in 1974, Jill Freedman was who he interviewed when talking about photographers. From the first time I saw her work, I knew that there was an extreme tension in how she approached it. “Sometimes it’s hard to get started, ’cause I’m always aware of invading privacy. If there’s someone who doesn’t want me to take their picture, I don’t. When should you shoot and when shouldn’t you? I’ve gotten pictures of cops beating people. Now they didn’t want their pictures taken. (Laughs.) That’s a different thing.”[i] Freedman walked a very thin line between rooting for the underdog yet respecting authority.

You can find out more about Jill Freedman at http://www.jillfreedman.com/. Resurrection City, 1968 was recently re-published and can be found for purchase at your favorite bookstore or online. Firehouse and Street Cops are no longer in print, but used copies can be found online.

[i] Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do by Studs Terkel Text © 1972, 1974 by Studs Terkel – The New Press, New York, 2004, Pg. 153-154

~ Mark Walton

Read More

Take The Long Way Home | Jon Claytor

July 25, 2022High culture has pretty much disappeared along with the dress code.

Read More

A – MAZE – ING LAUGHTER, 2009 | YUE MINJUN

July 28, 2022A – Maze – ing Laughter, 2009 | Yue Minjun 岳敏君

A bronze sculpture located in Morton Park in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

I NEVER knew anyone so keenly alive to a joke as the king was. He seemed to live only for joking. To tell a good story of the joke kind, and to tell it well, was the surest road to his favor. Thus it happened that his seven ministers were all noted for their accomplishments as jokers. They all took after the king, too, in being large, corpulent, oily men, as well as inimitable jokers.

(Edgar Allan Poe, Hop-Frog; Or, the Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs, 1849)

Art in the public sphere is often interesting: the intended meaning of the artist may be subsumed by the larger interpellation of the work by the publics or communities that interact with the artwork on a daily basis, or over extended periods of time. You don’t even need to consider the larger argument about monuments that proffer ideologies that were once celebrated and are now suspect (to say the least): Yue Minjun’s installation in Morton Park, in Vancouver, B.C., can’t help but have an unsettling quality, and critical analysis of his work has used the phrase ‘cynical realism’ repeatedly, though the artist seems somewhat neutral on that categorization….

Minjun’s larger than life characters are surely laughing at us, not with us – and their number, their intimidating nature, their grins and smiles that seem ready to eat us up, brought to mind Edgar Allan Poe’s dark story Hop – Frog (specifically the king and his ministers, with their ‘jocular’ abuses of those weaker than they) which I quoted at the beginning of this curator’s pick.

I do favour literary references when responding to visual arts, but this one is particularly apt. The synopsis of the story: The title character, a person with dwarfism taken from his homeland, becomes the jester of a king particularly fond of practical jokes. Taking revenge on the king and his cabinet for the king’s striking of his friend and fellow dwarf Trippetta, he dresses the king and his cabinet as orangutans for a masquerade. In front of the king’s guests, Hop-Frog murders them all by setting their costumes on fire before escaping with Trippetta. (from here)

But that description is a bit bloodless: Poe was erudite, especially in terms of more morbid, or caustic, turns of phrase, and his characters reflected this.

Hop Frog’s final declaration, in the story, and his last words before escaping, are these:

“Ah, ha!” said at length the infuriated jester. “Ah, ha! I begin to see who these people are now!” Here, pretending to scrutinize the king more closely, he held the flambeau to the flaxen coat which enveloped him, and which instantly burst into a sheet of vivid flame. In less than half a minute the whole eight ourang-outangs were blazing fiercely, amid the shrieks of the multitude who gazed at them from below, horror-stricken, and without the power to render them the slightest assistance.

At length the flames, suddenly increasing in virulence, forced the jester to climb higher up the chain, to be out of their reach; and, as he made this movement, the crowd again sank, for a brief instant, into silence. The dwarf seized his opportunity, and once more spoke:

“I now see distinctly.” he said, “what manner of people these maskers are. They are a great king and his seven privy-councillors, — a king who does not scruple to strike a defenceless girl and his seven councillors who abet him in the outrage. As for myself, I am simply Hop-Frog, the jester — and this is my last jest.”

Perhaps that scenario that Poe wrote – where those who mock are held to account – is a good one, to keep in mind as you wander the maze of these towering, awing figures that seem to cow us with their dramatic poses. But it would be remiss to not consider a less dour reading, which coincides with what brought these works to my attention – and that is from a recent rewatch I engaged in, focused on the iconic television series The X-Files.

To steal another’s words on this: Maybe the problem is that we’re confusing the mirror for the window and vice-versa. The fact that Mulder and Dr. They are discussing these provocative ideas among the fourteen statues that make up the “A-maze-ing Laughter” exhibit in Vancouver’s Morton Park adds another complicating layer. These bronze behemoths, each in a petrified state of hysterics, were conceived by the Beijing-based artist Yue Minjun as exaggerated self-portraits, and fall under the movement known as Cynical Realism, a response to the Chinese government’s oppressive approaches to aesthetic expression. Yet they’ve paradoxically brought such joy to a populace an ocean away that they’ve been made a permanent fixture of the Vancouver cityscape….Pain in one place begets gaiety in another, and even a calcified smile has the power to counteract, if not necessarily defeat, the despots. (from here)

All images are from Wikipedia Commons.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

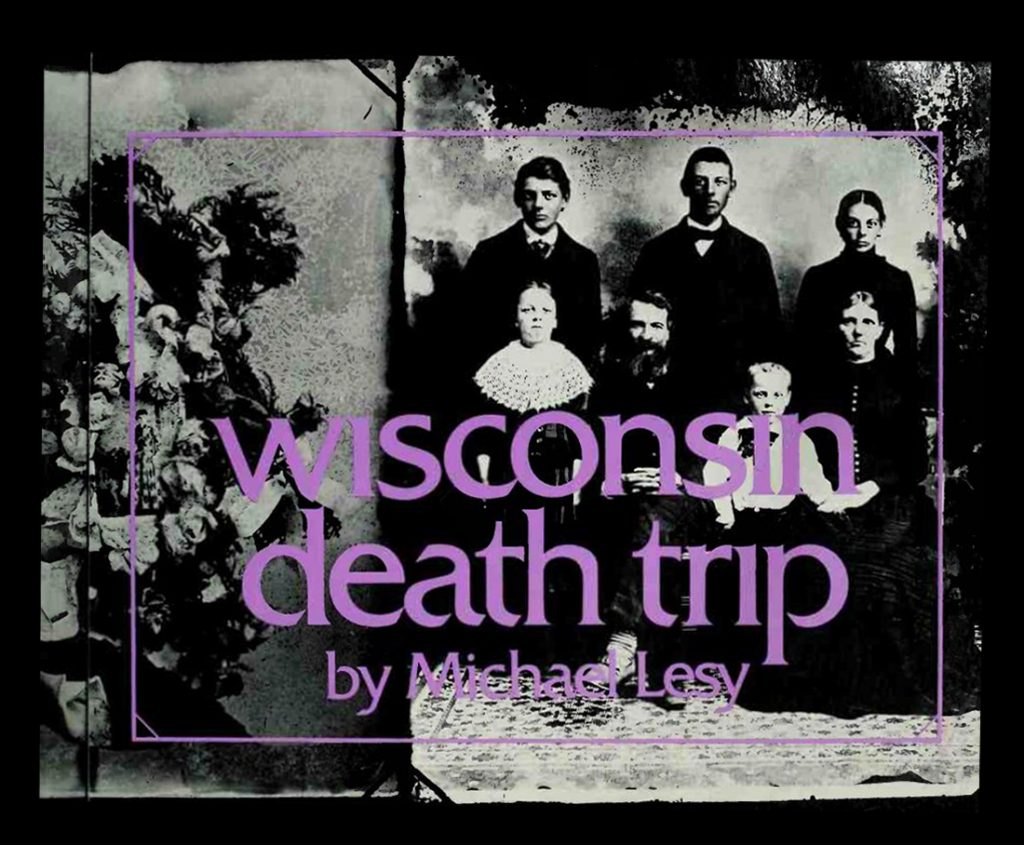

Wisconsin Death Trip | Michael Lesy, 1973

August 11, 2022Wisconsin Death Trip | Michael Lesy, 1973 (reprinted in 1991 by Anchor Books, and University of New Mexico Press in 2000)

Pause now. Draw back from it. There will be time again to experience and remember. For a minute, wait, and then set your mind to consider a different set of circumstances: consider those scholars and social philosophers who never knew that Anna Myinek had burned her employer’s barn or that Ada Arlington had shot her lover, but who nevertheless understood that something strange and extraordinary was happening in the middle of the continent at nearly the same instant that they sat in their studies, surrounded by their books. Such men did their best to understand what it meant, and in the process they tried to predict that future in which we are now enmeshed.

The only problem is how to change a portrait back into a person and how to change a sentence back into an event….The thing to worry about is meanings, not appearances.

I first became aware of Wisconsin Death Trip – the book by Michael Lesy and the James Marsh film it inspired, which I’m less impressed with – while reading Stephen King’s novella 1922, as King has mentioned it as inspiration. It’s one of those King stories that could be interpreted as flirting with the supernatural, but may, in fact, simply be everyday horror. 1922 tells the tale of an ignorant, greedy man on a failing, hardscrabble farm, who murders his wife and thus brings about the death of his beloved son (the ‘ghost’ of his wife returns, Banquo – like, to tell of this before his child’s body is even found). He survives only to suffer and regret, losing all he owned – and his hand, to infection – and is haunted, for years, by the rats that consumed his murdered wife’s body, that only he can hear, and suffers their chittering call and bites in the long dark nights until he takes his own life to escape….

Read more of Gazzola’s thoughts about Wisconsin Death Trip here.

Read More

Different Water

June 22, 2022Different Water A Discussion on Art featuring work by Chrystal Gray and Mayra Perez Whiskey Bottle by Mayra Perez, Mask and... Read More

The Chain Links

June 20, 2022Faki Kuano | Sarah Cheon | Ashley Guenette The Chain Links × × curated. by The COVERT Collective is pleased to... Read More

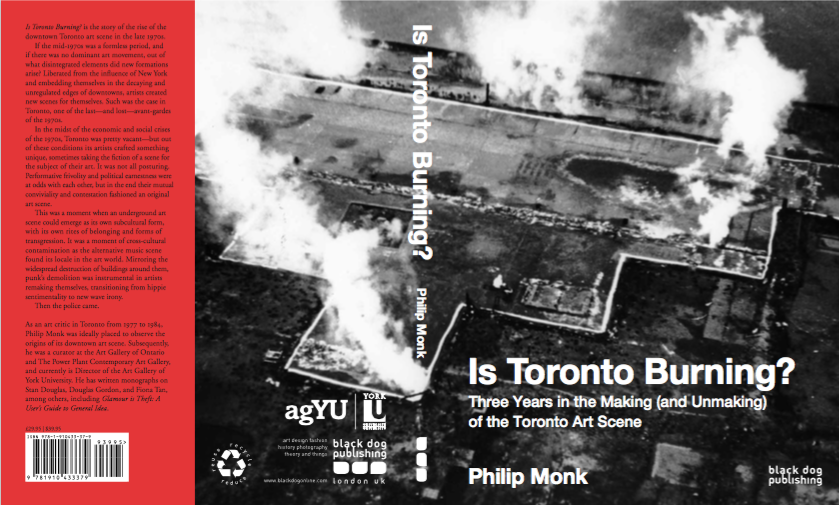

Philip Monk | Is Toronto Burning?: Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Community

July 7, 2022Philip Monk, Is Toronto Burning?: Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene, London: Black Dog Publishing, 2016.

Jack Pollock, Dear M: Letters from a Gentleman of Excess, McClelland & Stewart, 1989

“Each day I write. I’m not sure what it’s all about, but most days I write about art and the constant raping of its values by pseudo intellectual acrobats.” (Jack Pollock, Dear M: Letters from a Gentleman of Excess)

Nothing seems more improbable than what people believed when this belief has gone with the wind. (Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook)

“Culture has replaced brutality as a means of maintaining the status quo.” (Philip Monk, Is Toronto Burning? Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene)

A spate of old issues of FILE magazine came into my hands over the past year (it’s worth noting that they were a gift from Elizabeth Chitty, who also gave me the copy of Monk’s book that spurred this essay). They’re a bit ragged, but that seems appropriate, as they’re like flashbacks (the magazine began publishing in 1972 and ran for 17 years, with 26 issues) that don’t resonate with many, more nostalgia than substance.

They seem very dated, at times very juvenile, and more of an exercise in artistic onanism than anything else. This is, of course, a generalization, and it’s broken in certain points quite clearly. The issue that is almost entirely colour images of the three poodles, one of the many symbolic personas of General Idea, engaged in various tumbling and enthusiastic sex acts is one to keep (as I was impressed when I saw one of the large paintings from this series on a trip to the Art Gallery of Hamilton, installed amidst other notable Canadian works from Graham Coughtry to Attila Lukacs).

But many of the other copies of FILE are easily dismissed, even by someone like myself who has made a career of excavating in spaces that are too often ignored as pertains to Canadian Art history. The odd flash of brilliance, or the appropriation of mainstream media narratives and iconography, the sampling of authors from Burroughs to Acker, are the exception, not the rule.

Perhaps, this many decades later, our expectations of how artists engage in appropriation is more sophisticated – or more jaded. Edit as you will.

But all this reminded me of my long overdue response to Philip Monk’s book Is Toronto Burning? Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene), published several years ago, and that is focused upon the same era. I found the book uneven, and some players and characters in this story seem somewhat incongruous to their later roles or personas (true or assigned, in that vague way of art history and cultural narratives). But Monk’s own words lead to this: “In a sense, what follows is a story, a story with a cast of characters. These characters are pictured in video, photography, and print – not necessarily as portraits but rather as performers.” (from the chapter 1977). But in finally offering my impression of Monk’s narrative (considering personal and public factors and all the sites where those contested narratives collude and collide), I’ll begin with the following assertion: “All narrators are unreliable. Especially when they are characters within their own story.”

Read more here.

Read More

Recent Comments