In: curated

Menashe Kadisman | Shalechet (Fallen Leaves), 1997 – 2001

August 19, 2022Menashe Kadishman | Shalechet (Fallen Leaves), 1997 – 2001

Installation, Jewish Museum, Berlin

When we were young, we wanted our art to change the world. But when Hitler bombed Guernica, did Picasso’s painting have any effect? I thought that maybe some things of mine could do good. My sculptures didn’t change the war in Lebanon. Maybe art is not about changing anything. It’s about telling you reality. (Menashe Kadishman)

I will admit that I rely upon the term ‘contested narratives’ a bit too much: but when confronted with Kadishman’s installation, where his own personal history (as the child of two committed Zionists, in the early twentieth century) and larger tropes intersect, contradict and in some ways twist and transform in a manner that is more apropos to a fictional story than our expectations of ‘reality’, I feel I have no recourse.

Kadishman’s installation is “primarily associated with the Shoah (the Holocaust) [but] it holds a universal message against violence and human suffering. Kadishman himself notes that the work can relate to different tragedies such as World War I and Hiroshima. In part, Shalechet derives its meaning from the context of its presentation. For example, it took on a new meaning in 2018, when it was exhibited at the Memorial Hall dedicated to the victims of the Nanjing massacre in China.” (I include a link as this horror is lesser known, in the cacophony of savagery that is human history, like the many – repetitive, interchangeable, eternal – ‘faces’ silently wailing on the floor of Shalechet, growing old and rusting and still unheard….)

Read more of Gazzola’s response to this work here.

Read More

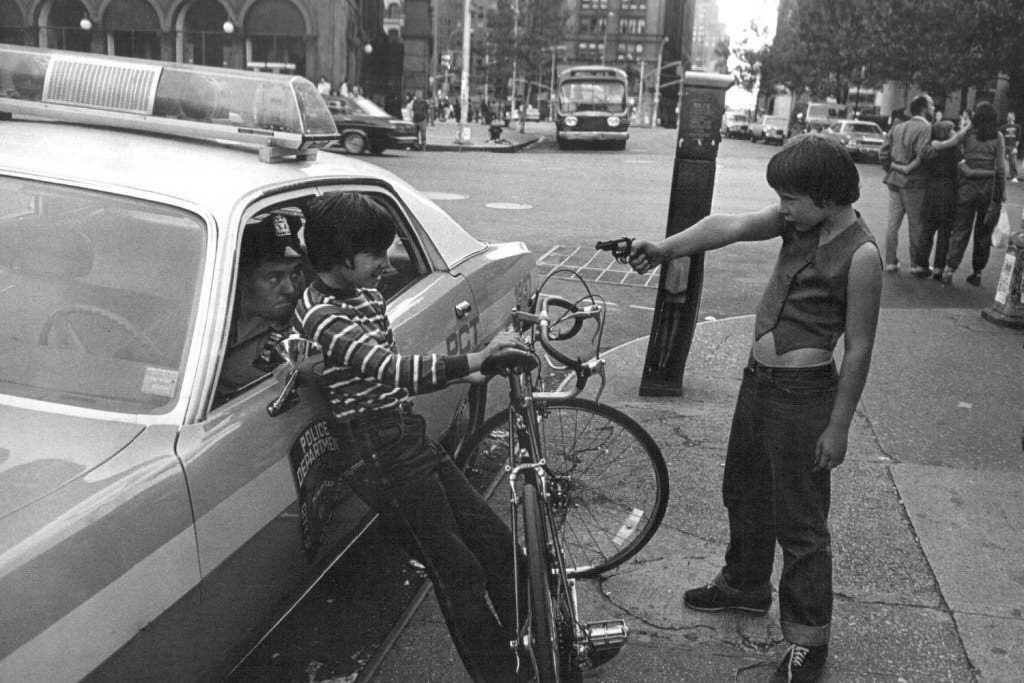

Gun Play | Jill Freedman

August 8, 2022Jill Freedman is a name you should know in the world of photography… but more than likely don’t. With a career that spanned 40 years, 7 (and counting) books and pieces acquired by major galleries, Freedman’s work connects deeply with her subjects in a manner unlike most documentary photographers.

From the very beginning, Jill was IN. She didn’t go to take photos of Resurrection City in Washington in 1968; she LIVED in the camp with the protesters for the duration of that campaign. She travelled with the circus for several months in the early 70’s to get her incredible photos of life under and around the big top. She embedded herself in the firehouses and police precincts of NYC and came out with work so beautiful and intimate that her two books on the subjects (Firehouse and Street Cops) were snapped up by first responders when they were re-released in the early 2000’s.

When Pulitzer Prize winner Studs Terkel wrote his oral history Working in 1974, Jill Freedman was who he interviewed when talking about photographers. From the first time I saw her work, I knew that there was an extreme tension in how she approached it. “Sometimes it’s hard to get started, ’cause I’m always aware of invading privacy. If there’s someone who doesn’t want me to take their picture, I don’t. When should you shoot and when shouldn’t you? I’ve gotten pictures of cops beating people. Now they didn’t want their pictures taken. (Laughs.) That’s a different thing.”[i] Freedman walked a very thin line between rooting for the underdog yet respecting authority.

You can find out more about Jill Freedman at http://www.jillfreedman.com/. Resurrection City, 1968 was recently re-published and can be found for purchase at your favorite bookstore or online. Firehouse and Street Cops are no longer in print, but used copies can be found online.

[i] Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do by Studs Terkel Text © 1972, 1974 by Studs Terkel – The New Press, New York, 2004, Pg. 153-154

~ Mark Walton

Read More

Take The Long Way Home | Jon Claytor

July 25, 2022High culture has pretty much disappeared along with the dress code.

Read More

A – MAZE – ING LAUGHTER, 2009 | YUE MINJUN

July 28, 2022A – Maze – ing Laughter, 2009 | Yue Minjun 岳敏君

A bronze sculpture located in Morton Park in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

I NEVER knew anyone so keenly alive to a joke as the king was. He seemed to live only for joking. To tell a good story of the joke kind, and to tell it well, was the surest road to his favor. Thus it happened that his seven ministers were all noted for their accomplishments as jokers. They all took after the king, too, in being large, corpulent, oily men, as well as inimitable jokers.

(Edgar Allan Poe, Hop-Frog; Or, the Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs, 1849)

Art in the public sphere is often interesting: the intended meaning of the artist may be subsumed by the larger interpellation of the work by the publics or communities that interact with the artwork on a daily basis, or over extended periods of time. You don’t even need to consider the larger argument about monuments that proffer ideologies that were once celebrated and are now suspect (to say the least): Yue Minjun’s installation in Morton Park, in Vancouver, B.C., can’t help but have an unsettling quality, and critical analysis of his work has used the phrase ‘cynical realism’ repeatedly, though the artist seems somewhat neutral on that categorization….

Minjun’s larger than life characters are surely laughing at us, not with us – and their number, their intimidating nature, their grins and smiles that seem ready to eat us up, brought to mind Edgar Allan Poe’s dark story Hop – Frog (specifically the king and his ministers, with their ‘jocular’ abuses of those weaker than they) which I quoted at the beginning of this curator’s pick.

I do favour literary references when responding to visual arts, but this one is particularly apt. The synopsis of the story: The title character, a person with dwarfism taken from his homeland, becomes the jester of a king particularly fond of practical jokes. Taking revenge on the king and his cabinet for the king’s striking of his friend and fellow dwarf Trippetta, he dresses the king and his cabinet as orangutans for a masquerade. In front of the king’s guests, Hop-Frog murders them all by setting their costumes on fire before escaping with Trippetta. (from here)

But that description is a bit bloodless: Poe was erudite, especially in terms of more morbid, or caustic, turns of phrase, and his characters reflected this.

Hop Frog’s final declaration, in the story, and his last words before escaping, are these:

“Ah, ha!” said at length the infuriated jester. “Ah, ha! I begin to see who these people are now!” Here, pretending to scrutinize the king more closely, he held the flambeau to the flaxen coat which enveloped him, and which instantly burst into a sheet of vivid flame. In less than half a minute the whole eight ourang-outangs were blazing fiercely, amid the shrieks of the multitude who gazed at them from below, horror-stricken, and without the power to render them the slightest assistance.

At length the flames, suddenly increasing in virulence, forced the jester to climb higher up the chain, to be out of their reach; and, as he made this movement, the crowd again sank, for a brief instant, into silence. The dwarf seized his opportunity, and once more spoke:

“I now see distinctly.” he said, “what manner of people these maskers are. They are a great king and his seven privy-councillors, — a king who does not scruple to strike a defenceless girl and his seven councillors who abet him in the outrage. As for myself, I am simply Hop-Frog, the jester — and this is my last jest.”

Perhaps that scenario that Poe wrote – where those who mock are held to account – is a good one, to keep in mind as you wander the maze of these towering, awing figures that seem to cow us with their dramatic poses. But it would be remiss to not consider a less dour reading, which coincides with what brought these works to my attention – and that is from a recent rewatch I engaged in, focused on the iconic television series The X-Files.

To steal another’s words on this: Maybe the problem is that we’re confusing the mirror for the window and vice-versa. The fact that Mulder and Dr. They are discussing these provocative ideas among the fourteen statues that make up the “A-maze-ing Laughter” exhibit in Vancouver’s Morton Park adds another complicating layer. These bronze behemoths, each in a petrified state of hysterics, were conceived by the Beijing-based artist Yue Minjun as exaggerated self-portraits, and fall under the movement known as Cynical Realism, a response to the Chinese government’s oppressive approaches to aesthetic expression. Yet they’ve paradoxically brought such joy to a populace an ocean away that they’ve been made a permanent fixture of the Vancouver cityscape….Pain in one place begets gaiety in another, and even a calcified smile has the power to counteract, if not necessarily defeat, the despots. (from here)

All images are from Wikipedia Commons.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

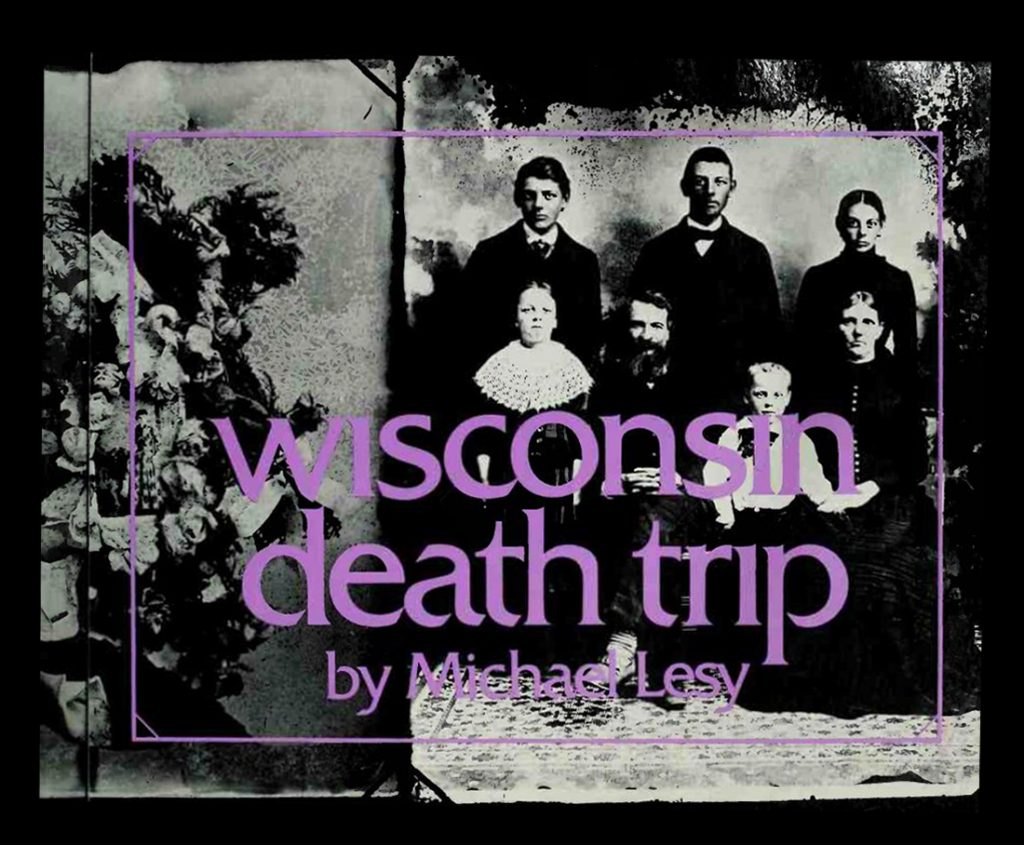

Wisconsin Death Trip | Michael Lesy, 1973

August 11, 2022Wisconsin Death Trip | Michael Lesy, 1973 (reprinted in 1991 by Anchor Books, and University of New Mexico Press in 2000)

Pause now. Draw back from it. There will be time again to experience and remember. For a minute, wait, and then set your mind to consider a different set of circumstances: consider those scholars and social philosophers who never knew that Anna Myinek had burned her employer’s barn or that Ada Arlington had shot her lover, but who nevertheless understood that something strange and extraordinary was happening in the middle of the continent at nearly the same instant that they sat in their studies, surrounded by their books. Such men did their best to understand what it meant, and in the process they tried to predict that future in which we are now enmeshed.

The only problem is how to change a portrait back into a person and how to change a sentence back into an event….The thing to worry about is meanings, not appearances.

I first became aware of Wisconsin Death Trip – the book by Michael Lesy and the James Marsh film it inspired, which I’m less impressed with – while reading Stephen King’s novella 1922, as King has mentioned it as inspiration. It’s one of those King stories that could be interpreted as flirting with the supernatural, but may, in fact, simply be everyday horror. 1922 tells the tale of an ignorant, greedy man on a failing, hardscrabble farm, who murders his wife and thus brings about the death of his beloved son (the ‘ghost’ of his wife returns, Banquo – like, to tell of this before his child’s body is even found). He survives only to suffer and regret, losing all he owned – and his hand, to infection – and is haunted, for years, by the rats that consumed his murdered wife’s body, that only he can hear, and suffers their chittering call and bites in the long dark nights until he takes his own life to escape….

Read more of Gazzola’s thoughts about Wisconsin Death Trip here.

Read More

Different Water

June 22, 2022Different Water A Discussion on Art featuring work by Chrystal Gray and Mayra Perez Whiskey Bottle by Mayra Perez, Mask and... Read More

The Chain Links

June 20, 2022Faki Kuano | Sarah Cheon | Ashley Guenette The Chain Links × × curated. by The COVERT Collective is pleased to... Read More

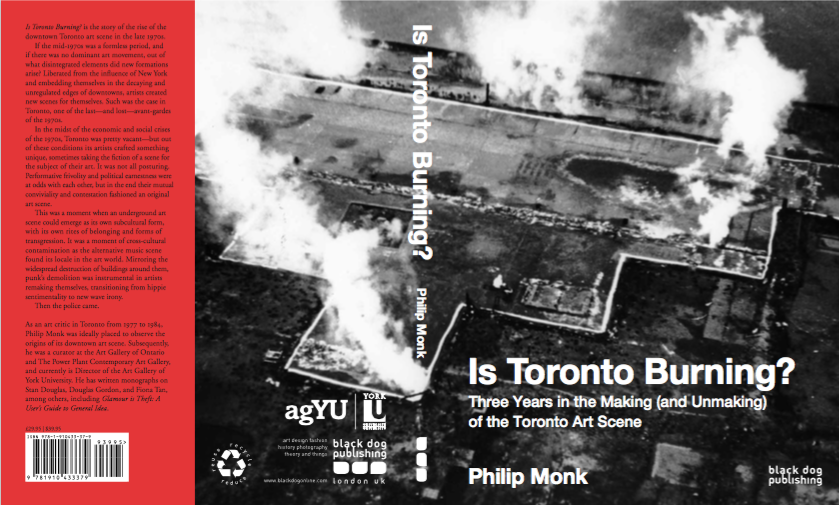

Philip Monk | Is Toronto Burning?: Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Community

July 7, 2022Philip Monk, Is Toronto Burning?: Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene, London: Black Dog Publishing, 2016.

Jack Pollock, Dear M: Letters from a Gentleman of Excess, McClelland & Stewart, 1989

“Each day I write. I’m not sure what it’s all about, but most days I write about art and the constant raping of its values by pseudo intellectual acrobats.” (Jack Pollock, Dear M: Letters from a Gentleman of Excess)

Nothing seems more improbable than what people believed when this belief has gone with the wind. (Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook)

“Culture has replaced brutality as a means of maintaining the status quo.” (Philip Monk, Is Toronto Burning? Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene)

A spate of old issues of FILE magazine came into my hands over the past year (it’s worth noting that they were a gift from Elizabeth Chitty, who also gave me the copy of Monk’s book that spurred this essay). They’re a bit ragged, but that seems appropriate, as they’re like flashbacks (the magazine began publishing in 1972 and ran for 17 years, with 26 issues) that don’t resonate with many, more nostalgia than substance.

They seem very dated, at times very juvenile, and more of an exercise in artistic onanism than anything else. This is, of course, a generalization, and it’s broken in certain points quite clearly. The issue that is almost entirely colour images of the three poodles, one of the many symbolic personas of General Idea, engaged in various tumbling and enthusiastic sex acts is one to keep (as I was impressed when I saw one of the large paintings from this series on a trip to the Art Gallery of Hamilton, installed amidst other notable Canadian works from Graham Coughtry to Attila Lukacs).

But many of the other copies of FILE are easily dismissed, even by someone like myself who has made a career of excavating in spaces that are too often ignored as pertains to Canadian Art history. The odd flash of brilliance, or the appropriation of mainstream media narratives and iconography, the sampling of authors from Burroughs to Acker, are the exception, not the rule.

Perhaps, this many decades later, our expectations of how artists engage in appropriation is more sophisticated – or more jaded. Edit as you will.

But all this reminded me of my long overdue response to Philip Monk’s book Is Toronto Burning? Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene), published several years ago, and that is focused upon the same era. I found the book uneven, and some players and characters in this story seem somewhat incongruous to their later roles or personas (true or assigned, in that vague way of art history and cultural narratives). But Monk’s own words lead to this: “In a sense, what follows is a story, a story with a cast of characters. These characters are pictured in video, photography, and print – not necessarily as portraits but rather as performers.” (from the chapter 1977). But in finally offering my impression of Monk’s narrative (considering personal and public factors and all the sites where those contested narratives collude and collide), I’ll begin with the following assertion: “All narrators are unreliable. Especially when they are characters within their own story.”

Read more here.

Read More

Necropolis | Jon Lepp

May 18, 2022Necropolis | Jon Lepp Necropolis | Jon Lepp, The Open for Business Series @deadendstories Photographs, [Virginia] Woolf claims, "are not an... Read More

Tony Calzetta – Art Is Hell

April 22, 2022Tony Calzetta Art Is Hell Bart Gazzola sat down to talk with Tony Calzetta, whose decades long practice has been both... Read More

Recent Comments