In: Female Artists

Alys Tomlinson | Dead Time | 2004 – 2006

June 23, 2023Alys Tomlinson | Dead Time | 2004 – 2006

“I like to remember things my own way.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“How I remember them. Not necessarily the way they happened.”

(from Lost Highway)

I’ve recently begun rewatching the third season of Twin Peaks (I mention this as Alys Tomlinson has spoken of Dead Time with allusions to the painter Edward Hopper but also that ephemeral notion of the Lynchian landscape): there’s a scene where Shawn Colvin’s version of Viva Las Vegas is a soft and enchanting soundtrack to the unfolding scene, and I happened to be listening to that song as I was perusing Tomlinson’s Dead Time series online. Vegas is, they say, a place where time is fluid, or can be lost or doesn’t exist in the same manner as elsewhere….

Tomlinson’s scenes are more Lynch’s Mulholland Drive or Lost Highway than Twin Peaks, with harsh artificial light casting edged shadows and revealing a sinister tableaux. Some critics have spoken of how time in the Lynchian universe – especially in Twin Peaks – is non linear, and Tomlinson’s images have an eerie familiarity (I’ve also travelled long distances by car and spent evenings in motels that, in recollection, blur together into one continuous banal experience).

There’s an element of the same unsettling darkness and emptiness that Steve Laurie employs in some of his images that also invite us to see them as film stills and create our own narratives for them. Tomlinson’s ‘America’ is empty, hard and bright. Swimming pools – usually sites of social interaction and enjoyment – are harbingers that seem more nefarious, here.

“For the past few years Alys has been photographing empty swimming pools at night in the UK and abroad. The images explore a twilight world of the in-between: a blurring of day and night, light and dark, the open and the enclosed, plenitude and absence. Whether municipal or members only, the pool is a space shaped by its patrons. Captured out of use, these familiar spaces stand outside time. Curved light breaks up the horizontal rigour. The comfort of transparency gives way to reflection and shadow. What is cedes to what could be, and the ordinary is transformed. The geographical location of each swimming pool is kept secret. Shot at dusk or at night, the pools take on a detached, almost melancholy, emptiness, and suggest a sinister feeling that something has happened, or is about to happen.” (from here)

Alys Tomlinson’s site can be seen here (she’s an award winning photographer and the diversity of her work speaks to her acumen with a lens, both formally and conceptually) and her IG is here. She has produced a book of these images, as well.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Judith Schaechter | Eastern State Penitentiary | 2010-2011

June 16, 2023Judith Schaechter | Eastern State Penitentiary | 2010-2011

Schaechter works in a medium – stained glass – that is often consigned to the past, a method that most would be surprised to find is still employed by various artists. In terms of this, her thematic choices for this series of works installed in the Eastern State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania being a re interpretation of an allegory (most notably executed in 1559 by Pieter Breugel the Elder) that dates back over a thousand years is a melding of material and intent that literally shines.

It’s installation in a penitentiary offers even further intersections about indulgence and discipline, redemption and rashness, but also harkens to how this was a form of art that was essentially populist, offering narratives and stories to any who encounter it, even in unexpected places that foster moments of unanticipated joy.

Judith Schaechter is a very accomplished artist. She has lived and worked in Philadelphia since graduating in 1983 with a BFA from the Rhode Island School of Design Glass Program. She has exhibited widely across the United States, and has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, two National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships in Crafts, The Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, The Joan Mitchell Award, two Pennsylvania Council on the Arts awards, The Pew Fellowship in the Arts, and a Leeway Foundation grant, and she is a 2008 USA Artists Rockefeller Fellow. Much more about her impressive career can be seen here.

An excerpt from her statement about her work:

“I found the beauty of glass to be the perfect counterpoint to ugly and difficult subjects. A radiant, transparent, glowing figure is not the same as a picture of a figure (which reflects light). It’s a blatant reference to holiness or some type of “supernatural” state of being. In terms of my figures, although they are intended to be ordinary people doing ordinary things, I see them as having much in common with the old medieval windows of saints and martyrs.

They seem to be caught in a transitional moment when despair becomes hope or darkness becomes inspiration. They seem poised between the threshold of everyday reality and epiphany, caught between tragedy and comedy.

It seems my work is centered on the idea of transforming the wretched into the beautiful in theme as well as design. For me, this means taking what is typically negative — say, unspeakable grief, unbearable sentimentality, or nerve-wracking ambivalence, and representing it in such a way that it is inviting and safe to contemplate and captivating to observe (to avoid ending with preposition). I am at one with those who believe art is a way of feeling one’s feelings in a deeper, more poignant way.

Medieval windows sought to confer inspiration and enlightenment to those who would see it. Beholding a stained glass window can enable, encourage, and literally enact the process of being filled with light. It sounds like some kind of preternatural phenomenon, but it’s a physical fact. While one is busy identifying and empathizing with the image, one also physically experiences the warming, filling sensations of light. It’s so persuasive not because the pictures are convincing narratives but because the colors are overwhelming and the light is sublime…”

Besides the imposing – perhaps edifying, considering its location – Lent work, Schaechter has also interspersed smaller slim artworks in various sites in the Penitentiary, with titles that evoke emotion and consideration like The Weeping Chorus, Confines, Mother or Sister.

Prisons are spaces that we ignore in most conversations about society, let alone cultural communities: except for when the ‘debate’ rears its ugly head in the public sphere about whether they are spaces designed for rehabilitation or purely for a punitive joy that usually seems to have a vague stench of hypocrisy about it. In imagining what it would be like to stand in the presence of these works, the idea of ‘redemption’ – a word I am uncomfortable with, as like too many words it is used with a biased or easy intent – comes to mind.

More of Judith Schaechter’s unique artwork can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Liz Sexton

June 9, 2023Liz Sexton

“You aren’t a tiger. You’re a rat. No, that’s an insult to a noble and numerous species of rodent. You’re less than a rat.”

(Neil Gaiman, Anansi Boys)

When considering Liz Sexton’s Rat mask (which the artist created for Halloween and was documented in Brooklyn, New York, several years ago, amidst the visceral urban subway) and the stylish, self possessed Ratman I am initially reminded of the Rats (note the capitalization) and the Rat Speakers from the book Neverwhere.

Humour and horror (both heavily flavoured with the absurd in a delightfully performative manner) inform Sexton’s works. That’s one of the reasons why I included the images with her cat among those I’m sharing, as the cat’s unimpressed languor challenge the stoic existential nature of her ‘players’ (sometimes Sexton is the one donning the masks, other times not) that become something so much more in her masks, especially as they trod the public sphere. The Ravens (yes, I feel the need to formalize the characters in these scenes) on the subway may be harbingers of doom (if we’ve learned nothing from Edgar Allen Poe, don’t ask a Raven a question you don’t want answered, ahem) or simply out for the evening, on the way to meet fellow feathered friends : please don’t bother them, as a group of ravens IS called an ‘Unkindness.’

Other characters are engaged in equally banal every day activities, while others gaze directly back at us in a challenging manner, and others are captured in quiet moments of introspection, where we seem to be intruding on private moments.

Whether these are ‘disguises’ or new personas, I leave to your own discretion in any conclusion you make.

The words of the artist : “Most everything I create is meant to be interacted with, whether masks, puppets, or simply objects—they’re all intended to be worn, held, or touched….With the wearer concealed under a larger-than-life mask, it becomes as much a human with an animal head as an animal with a human body—a very interesting thing to interact with.

I often work on threatened species, particularly sea creatures, and photograph the animal masks worn in very human habits, highlighting the displacement that many creatures are currently experiencing. I also work on more common animals that we might share our surroundings with but don’t necessarily notice or engage with. Presented on a human scale, they share our world, becoming visible members of our communities.“ (from here)

In this light, I am also reminded of the moment – in Welland’s rust belt wonderland – when I met up with a fox late at night. Their unflinching gaze let me know who was the interloper, and it wasn’t them….

Liz Sexton has lived and worked in Paris, Berlin, and New York, and has recently returned to her Midwest roots, calling Saint Paul, Minnesota home. For now. Experienced in a wide range of mediums, these days she favors paper mâché for its versatility and accessibility. She enjoys creating sculptural objects, often inspired by the natural world.

Liz Sexton’s solo exhibition Out of Water is on view at the Minnesota Marine Art Museum May 6 – September 3, 2023.

Much more of her work can be enjoyed at her site here and her IG can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Hifa Cybe | Girl with the Gas Mask | 2020

June 3, 2023Hifa Cybe | Girl with the Gas Mask | 2020

I have heard the languages of apocalypse, and now I shall embrace the silence.

(Neil Gaiman)

Did you see the frightened ones?

Did you hear the falling bombs?

Did you ever wonder why we had to run for shelter when the promise of a brave new world unfurled beneath the clear blue sky?

(Goodbye Blue Sky, Pink Floyd)

I am convinced – though I’ve had difficulty tracking it down – that I read a line in Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, where one of the characters is talking of how, during the Russian civil war between the Whites and the Bolsheviks, it was a time when children only survived by eating the flesh of the dead (my memory of this line, even if invented, is quite visceral, and that intersects with some of Hifa Cybe’s work about memory – the veracity of it in personal narratives – too).

The quote I begin this piece with is – as some of you will know – from Pink Floyd’s The Wall, and this song always struck a chord regarding how in post WW II Britain a hoped for peace gave way to the Cold War, and that the idea – the fear – of an impending nuclear apocalypse – that we might bring about our own ending in a previously unimaginable manner – suffused a generation of children, as dour and suffocating and infecting as the bombs that ravaged people during WWII, and that do so still, now, perhaps forever….

I have little to actually say about Cybe’s artwork here : it’s power, simplicity in contradictions and the anxiety it induces are so intensely visual, so well executed, that my words would simply be a barrier to the viewer’s immediate engagement with it. An image like this also exposes the trite self aggrandizing act of Ai Weiei’s ‘reimagining’ of the image of drowned infant Alan Kurdi that in 2015 became the defining symbol of the plight of Syria’s refugees.

There is one thing to consider, though, in light of how Cybe’s research and artworks delve into trauma, especially in terms of memory and childhood. Here, in Niagara (as I make this post at the beginning of Pride month), we’re seeing the latest iteration of hatred against LBQT+ people, with a recent bilious spurt of it from a catholic school trustee : surely I’m not the only one who finds the rank stench of that hypocrisy, from a cult that has harmed so many – and so many children – too much? With this in mind, and looking at Cybe’s image, I am also reminded of friends I grew up with, in extremist religious environments, and that this scene might be a more exact psychological representation of their experiences, and tools of survival….

Luiza Jesus Prado, known as Hifa Cybe, is a transdisciplinary artist born in Guaratingueta, Brazil. She uses artistic tools such as photography, performance, video art, installation, sculpture, painting, new media, body art, music and drawing along with physics, psychology, neuroscience and philosophy. Cybe’s research is specifically on memory and the artist often explores topics of violence, sexual trauma, sociopolitical issues and minorities within Latin America.

This image is from a larger body of work under the aegis of Photo Homeostasis – Reprocessing Memories of Violence. The quote I began this essay with – from Neil Gaiman – is also the closing salvo from one of his stories in Endless Nights, which speaks of survival and even strength in the face of trauma.

Much more of Hifa Cybe’s artwork and research can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Dorothea Lange | A family of drought refugees from Abilene, Texas, on the road in California | 1936

May 4, 2023Dorothea Lange (1895 – 1965) | A family of drought refugees from Abilene, Texas, on the road in California | 1936

“The depression was making people disappear.

They vanished from factories and warehouses and workshops, the number of toilers halving, then halving again, until finally all were gone, the doors closed and padlocked, the buildings like tombs. They vanished from the lunchtime spots where they used to congregate, the diners and deli counters where they would grab coffee on the way in or a slice of pie on the way out.

They disappeared from the streets.

They were whisked from the apartments whose rents they couldn’t meet and carted out of the homes whose mortgages they couldn’t keep pace with, lending once thriving neighborhoods a desolate air, broken windows on porches and trash strewn across overgrown yards. They disappeared from the buses and streetcars, choosing to wear out their shoe leather rather than drop another dime down the driver’s metal bucket. They disappeared from shops and markets, because if you yourself could spend a few hours to build it, sew it, repair it, reline it, reshod it, reclod it, or reinvent it for some other purpose, you sure as hell weren’t going to buy a new one.

They disappeared from bedrooms, seeking solace where they could: a speakeasy, or, once the mistake of Prohibition had been corrected, a reopened tavern, or another woman’s arms—someone who might not have known their name and certainly didn’t know their faults well enough to judge them, someone who needed a laugh as badly as they did.

They disappeared, but never before your eyes; they never had that magic. It was like a shadow when the sun has set; you don’t notice the shadow’s absence because you expect it. But the next morning the sun rises, and the shadow’s still gone.”

(Thomas Mullen, The Many Deaths of the Firefly Brothers)

I have a tendency in my research to fall down rabbit holes: this is often shaped by history (my interest – which has manifested on this site – in post Soviet artists, for example) and of late The Great Depression has been a point of interest. My enjoyment of horror intersects here, so I will confess that I came to the author that I quote liberally above (whose book follows two brothers whom are bank robbers during the Great Depression, harshly factual and researched, but they find they are resurrected each time they’re killed in one of their robberies) through Daniel Knauf’s Carnivàle series. But, like another writer has pointed out, improbability and violence overflow from ordinary life, and the Great Depression was a time more, perhaps, malleable than most, as many assumptions were fractured irreparably…

And the horrors experienced by many from the Crash of 1929 through the Depression were ‘unimaginable’ to many, until they became commonplace, and now, it seems, have been forgotten. This is similar to how we forget that Lange’s subjects are not just icons but actual people who lived, suffered and died.

To many, Lange’s work requires no introduction. Many of her photographs are so stitched into the fabric of a communal history that they act as signifiers for collective memories. Nonetheless: Dorothea Lange “was an American documentary photographer and photojournalist, best known for her Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Lange’s photographs influenced the development of documentary photography and humanized the consequences of the Great Depression.” (from here)

I return to Mullen’s book that had flavours of horror, but not in the way I expected, as it was more historical than ‘supernatural’ horror:

“Ten feet behind them, standing at the base of an arc light and looking in the opposite direction, was a young, balding man who Weston supposed was the father. The man looked as if he were trying very hard to become invisible.

When you bump into an old acquaintance on the street, you ask him how he’s doing. He tells you a story and then you tell him your story, and both of you are trying to see where you fit within the other’s. Your story says: This is the way the world is, and I’m the center, over here. But if the other guy tells a different story, with the world like this, where the center’s actually over here, then you realize that you’re way off to the side.

This man did not need to be told he was off to the side. He clearly realized it.”

More of Lange’s work – both her iconic images of The Great Depression and her later work that was more local but considered the same issues of justice and equality – can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Kristina Varaksina | Self portrait wrapped, 2020

April 27, 2023Kristina Varaksina | Self portrait wrapped, from the Self Reflection series, 2020

“Why do men feel threatened by women?” I asked a male friend of mine. (I love that wonderful rhetorical device, “a male friend of mine.” It’s often used by female journalists when they want to say something particularly bitchy but don’t want to be held responsible for it themselves. It also lets people know that you do have male friends, that you aren’t one of those fire-breathing mythical monsters, The Radical Feminists, who walk around with little pairs of scissors and kick men in the shins if they open doors for you. “A male friend of mine” also gives — let us admit it — a certain weight to the opinions expressed.)

So this male friend of mine, who does by the way exist, conveniently entered into the following dialogue. “I mean,” I said, “men are bigger, most of the time, they can run faster, strangle better, and they have on the average a lot more money and power.” “They’re afraid women will laugh at them,” he said. “Undercut their world view.”

Then I asked some women students in a quickie poetry seminar I was giving, “Why do women feel threatened by men?” “They’re afraid of being killed,” they said.

(Margaret Atwood, Second Words: Selected Critical Prose, 1982)

Kristina Varaksina received her Master’s in Photography from the Academy of Art University, San Francisco, in 2013. Born in Russia, Varaksina has resided in the USA since 2010 and currently divides her time between London and New York.

From here: “In her personal work, Varaksina explores the vulnerabilities, insecurities and self-search of a woman and an artist. Her work is a creative response to what’s going on in the world and her immediate environment. Through visual symbolism, carefully curated colour palettes and cinematic lighting she reflects the strongest emotions she and her subjects experience.” I would inject another line from Atwood here, in response: I’m working on my own life story. I don’t mean I’m putting it together; no, I’m taking it apart.

Varaksina gives voice to women from different ethnic, socio-economic, and cultural backgrounds, each doing their best to accept themselves as who they are and be proud of that. Varaksina sees her job as a photographer to make “ordinary” women more visible and therefore, more valuable.”

Varaksina has earned numerous awards for her work: her figures alternate between an unflinching gaze that challenges – perhaps unnerves – the viewer, and a stillness where our presence is neither requested or needed, intruding into the quiet being of her subjects. The Self Reflection series – which is ongoing – has been described as both ‘claustrophobic’ and a commentary on the history of portraiture in the Western canon. In this body of work, her stare is direct and unrelenting, as she not only turns her camera on herself as part of her work about women but turns her gaze upon us, too.

More of her work can be seen here. Varaksina’s IG is @kristinavaraksina

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Takayo Kiyota | Tama-Chan

April 6, 2023Takayo Kiyota | Tama-Chan

“That’s what you get for being food.”

― Margaret Atwood, The Edible Woman

Takayo Kiyota (also known as Tama-Chan) produces what can only be described as sushi art: some are playful, some are slightly more unsettling and others offer an interesting opportunity for dialogue about our relationship to food and larger assumptions around aesthetics.

In this artwork, Kiyota – who has interpreted famous works such as Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) or Vermeer’s Girl With A Pearl Earring | Meisje met de parel (1665) – re-imagines a painting that is well known but often misconstrued, sometimes in a bawdy manner.

Gabrielle d’Estrées et une de ses soeurs (Gabrielle d’Estrées and one of her sisters) was painted by an unknown artist (perhaps from the Fountainbleau School) around 1594. It can seen in the Louvre, in Paris: “The painting portrays Gabrielle d’Estrées, mistress of King Henry IV of France, sitting nude in a bath, holding a ring. Her sister Julienne-Hyppolite-Joséphine sits nude beside her and pinches d’Estrées’ right nipple.” More about this painting can be seen here.

Years ago, I experienced an audio environment / installation by Anitra Hamilton: the bare gallery space was inundated by two conflicting yet connected audible narratives. One section of the gallery was suffused by a recording of a Sotheby’s auction of artworks. The other was a cattle auction, with ‘prize’ animals going to the highest bidder. In a response to that exhibition I made some uncomfortable analogies to what we consume, how we value it, and the conversations around these things that ‘feed’ us.

Tama-chan (Takayo Kiyota) was born in Shinjuku, Tokyo. After graduating from the Setsu Mode Seminar she started to work in advertisement, magazines, and books as a freelance illustrator. Since 2005, she has called herself the sushi roll artist “Tama-chan.” Through workshops she has been introducing the importance of food culture, food education, as well as the joy of making things with her maki-sushi. In 2013, she won the second prize on “the longest scream in the world” sponsored by Innovation Norway. In 2014, Little More Co. published Smiling Sushi Roll, the first anthology of her work.

You can see more of these delicate and temporary artworks on IG : @smilingsushiroll39

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Pat Douthwaite | Bernard Berenson at Leptis Magna, 1966

March 31, 2023Pat Douthwaite | Bernard Berenson at Leptis Magna, 1966

I am only a picture-taster, the way others are wine – or tea – tasters.

Bernard Berenson

Years ago when I was on a panel talking about ‘modernism’ I offered a line from Clement Greenberg, that is one of my favourites (not solely for the idea expressed, but also as it seemed to fly in the face of many of the karaoke modernists who attended that discussion on the prairies who are sure ‘art’ ended with hard edged painting several decades ago): that we evaluate artwork with the criteria we have now, but fully understanding that this criteria can and must change.

Greenberg is one of the ‘old gods’ of the Western art canon – like Bernard Berenson, the erstwhile subject of this painting by Douthwaite. The site that Berenson is ‘visiting’ in this painting is of significant archeological important (more on that can be read here). Berenson (1865 – 1959) was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance, but his influence was much more than that, and he is one of the shoals of Western art history that is to be negotiated.

But – in deference to contested narratives, and considering how Douthwaite has, like too many female artists, not garnered the acclaim of some of her male colleagues – I also offer Atwood’s iconic line: “We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom. We lived in the gaps between the stories.” Douthwaite’s paintings have a striking originality, and though she’s often compared to Chaïm Soutine he is also – like Douthwaite – an artist whose work is immediately recognizable. This painting has a carnivalesque quality to it, and the ‘skulls’ suggest a merry dance of death…. she often “referred to herself as the “high priestess of the grotesque”, aptly describing her dedication to the arresting, often haunting, figurative work that carved out her place within British postwar art…[Douthwaite] was a distinctive and complex artist rather than [simply] a “difficult” woman, as she was sometimes described.” (from here)

Douthwaite’s approach is unique: ‘Instead of the traditional easel set up, Douthwaite preferred to paint on the floor: ‘I crawl around the floor on my knees, with a butcher’s apron round me, moving from drawing to drawing or canvas to canvas.’ She was unconventional in her painting technique too and rather than use brushes she worked the images up from the surface of the canvas using paint-soaked rags. She often depicts death with humour as if to underline the absurdity of life.’ (from here)

Pat Douthwaite was born in Glasgow in 1939 and initially studied mime and modern dance with Margaret Morris. She is primarily self taught, though in 1958 Pat lived in Suffolk with a group of painters. From 1959 to 1988 she travelled widely (North Africa, India, Peru, Venezuela, Europe, USA, Kashmir, Nepal, Pakistan, Ecuador) and from 1969 lived part of the time in Majorca. Douthwaite exhibited with the Women’s International Art Club in London between 1960 and 1966. She returned to spend the rest of her life in Scotland, passing away in 2002 at Dundee. In 2005 the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh mounted a memorial exhibition to mark her life and work.

Much more of her work can be seen here, and more about her life can be learned here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

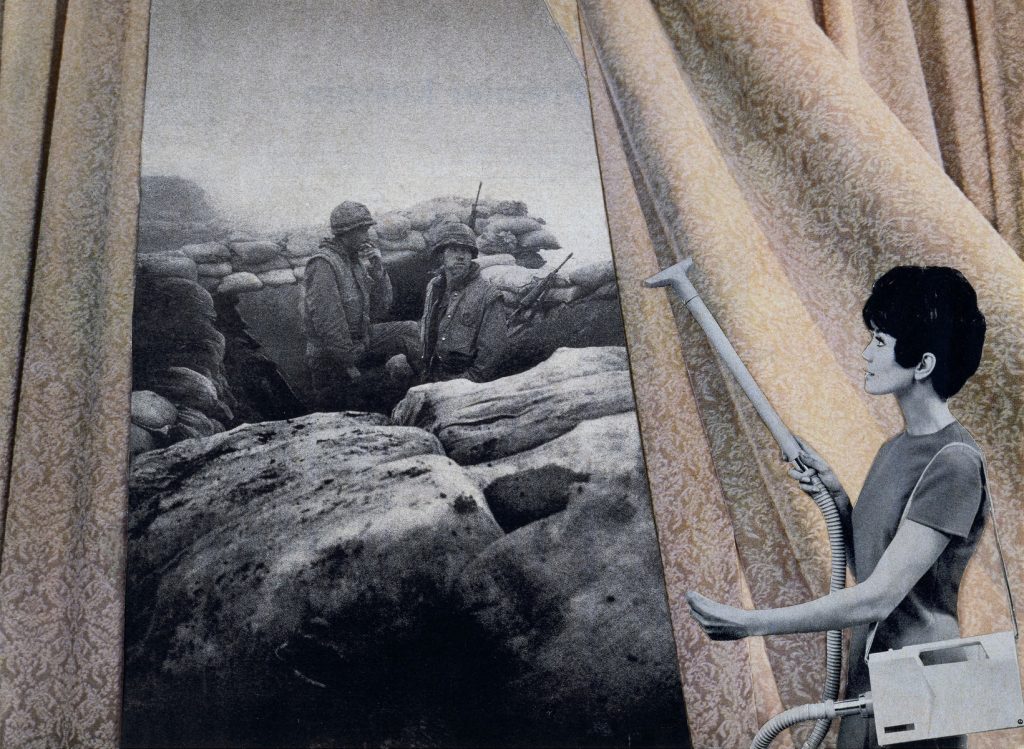

Martha Rosler | House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–1972

March 24, 2023Martha Rosler | House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–1972

Cotton’s generation grew up with a war in the house. For them, games of cops and robbers and cowboys and Indians no longer satisfied the senses. A boy had but to turn a control to be totally involved in the violent distension of experience that was Vietnam on television. Cotton became addicted to it. Vietnam was even a portable war.

A boy had but to move his personal set to have air strikes in the living room, search-and-destroy operations in the bedroom, naval bombardment in the bathroom—napalm before school, body bags before dinner.

(Glendon Swarthout, Bless the Beasts and the Children)

I recently read The Sacred Lies of Minnow Bly by Stephanie Oakes. The premise – of a young woman who survives a doomsday cult – sent me down a rabbit hole, if you will, of research on these cults, and since then I’ve been devouring a number of texts on the topic.

One of these – Jeffrey Melnick, Charles Manson’s Creepy Crawl: The Many Lives of America’s Most Infamous Family – offers an interesting supposition. Melnick argues that the Tate – LaBianca murders were used by many on the right – Nixon, for example – as a means by which to shutter debate about the (even then) failure of the nuclear family in the United States. This is similar to Zizek’s comment that most conversations about socialism always have a chicken little proclaiming it ‘will end in the gulag!’. Other societal issues are cast in a different light from the Manson murders, as well (for example, Melnick talks about the dismissive attitude towards runaways – especially girls – at that time, criminalizing or infantilizing them, using several of the Manson ‘family’ as examples, instead of focusing on larger issues within society).

Melnick dismisses with derision the idea that Manson ‘ended’ the supposed utopic dream of the 1960s – and for this post, a point he makes stays with me. Bluntly, that the violence of the Manson family was nary a drop in the bucket to the televised, sanctioned and officially endorsed violence of the war in Vietnam and other societal pressures. His words: “If the countercultural fabric got torn it was not because a few celebrities were killed in August of 1969. We would be better off attending to the plight of returning veterans, the not unconnected influx of harder drugs into American cities, the ongoing runaway crisis, and a major effort by the dominant culture—from the president on down—to repudiate and abandon young people and their culture.”

And this brings us to Martha Rosler’s series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, 1967–72.

The initial incarnation of this series was about Vietnam: in a despairing commentary about history Rosler would revisit and reinterpret it decades later, for the ‘war against terror’ in Iraq and Afghanistan…..

Rosler – in the tradition of artists like Hannah Höch – employs collage, using images that are familiar to us in tandem with others that fracture and trouble the original ‘homes’ on display. These might ‘homes’ in the literal sense, but also the ideologies and assumptions that inform those spaces, sometimes so implicitly that to highlight them engenders a denial of them, like a fish unaware of water as it’s so ubiquitous.

‘This work is one of twenty pieces from Rosler’s House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (c.1967-72) series created during, and influenced by, the Vietnam War. It was the first war in history that was literally brought into the homes of American people through the revolutionary new television set from which its horrors could be witnessed daily. It was often described as a “living room war” – a description loaded with strange poignancy as it shined a light on the eeriness of a nation living their everyday lives, ripe with consumerist concerns like keeping the stylish home drapes clean, all the while gruesome political realities took place elsewhere, becoming just another form of nightly entertainment in front of the tube.

Simultaneously, there is a feminist element to the work as it comments on the robotic mundaneness of female domestic work in the midst of global unrest. The idea of women striving to keep the house beautiful while war’s tragedies are omnipresent becomes almost comical, and presents a surreal picture about what we deem important. Recognizing the potential for manipulation in the photographic medium, Rosler once stated, “Any familiarity with photographic history shows that manipulation is integral to photography.”’ (from here)

More of Rosler’s extensive practice – and her roles as social critic and historian for more than half a century – can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Robin Claire Fox | Reflections

March 17, 2023Robin Claire Fox | Reflections

Photography is inherently nostalgic. Every image taken is essentially the capturing of a moment from the past. That moment no longer exists, just the memory of it and an analogue print or a digital impression trapped on an electronic device. Many modern photographers harbour longings for the saturated or contrasty renderings of images made with processes and media (like Kodachrome) long out of use or no longer in production. Quite a few of them try to recreate the look and feel of these processes digitally, running their captures through filters and algorithms to bring back the visual past. While many are overdone (why keep it at 3 when you can dial it up to 10?), there are a few who have mastered the ability to make us believe that we are viewing an image taken decades ago. The evocation of this photographic past is (I believe) an effort to physically reconnect with it in a way that seems familiar, safe and warm… like sitting with your family watching slides projections of photos from a vacation taken years ago.

Ancaster, Ontario’s Robin Fox started taking photographs around the time of the birth of her most recent child as a conscious attempt to document her family’s childhoods for her future self to enjoy. She is a natural at capturing the uncertainties alongside the joys of growing up. A huge fan of Saul Leiter’s colour work, she has found a method of perfectly capturing the deep saturation and contrast Leiter exhibited in his work with Kodachrome and other slide films[1] in the 1950’s. Her images seem imbued with palettes that exist only in the memory of childhood, where everything was so much bigger and the world was awash with primary colours.

Read More

Recent Comments