In: curators pick

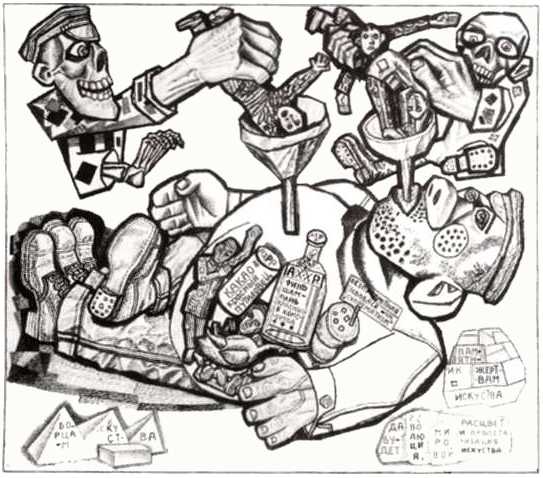

Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

October 21, 2022Pavel Filonov | The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, 1923

He was walking about with a noose round his neck and didn’t know. So I told him what I’d heard about his poems.

. . . . . . . .

Yevgraf: This is a new edition of the Lara poems.

Engineer: Yes, I know. We admire your brother very much.

Yevgraf: Yes, everybody seems to.. now.

Engineer: Well, we couldn’t admire him when we weren’t allowed to read him…

Yevgraf: …No.

(both quotes from Boris Pasternak’s tale of Russia before and after the Russian Revolution Dr. Zhivago)

A defining book in my reading and understanding of art history in the 20th century is Boris Groys’ The Total Art of Stalinism: begun when the USSR was still in existence, Groys was able, with the fall of that empire, to access more information, and offer a more nuanced take upon the years post Russian Revolution, as it pertains to the arts in that rare and unique historical moment. Amusingly, I became aware of it after participating in a panel about modernism, and horrifying my fellow speakers by stating that it had failed, horribly, but that its relevance was in its ideals…

Several points stay with me, in considering Pavel Filonov’s work. One is that, in a correlation to the backward economic state of Russia making it fertile ground for a radical new approach and the subsequent revolution, the artistic milieu also suffered from this. It’s not incidental that so many significant artists – not just to Russia but to ‘western’ art history – like Malevich or the Suprematists flourished during the first heady days of the NEP. Experimentation and a sentiment that ‘anything was possible’ was pervasive and defining, with a desire to irrevocably fracture from the ‘old.’

This, of course, all ended badly, and the promised freedoms – whether artistic or personal – were soon not just reigned in, but suppressed, and a cultural exodus from the USSR to other places was predictable.

Filonov (1883 – 1941) served in WWI and would die of starvation during the siege of Leningrad, the once and present St. Petersburg, in the war that followed the ‘war to end all wars.’

The painter, art theorist and poet was an outsider, even during the pre and immediately post revolutionary days of promise: after several failures, in “1908 Filonov was admitted at last to the Academy of Arts. His works attracted the attention of both students and professors by their unusualness: they were not abstract and depicted their subject with full likeness, but were executed in garish, bright colors – reds, blues, greens and oranges. This manner did not conform to the Academy standards, and Filonov was dismissed “for influencing students with the lewdness of his work”. Filonov protested the decision of the rector Beklemishev, and was rehabilitated, but after studying for two years he left the Academy in 1910.”

He was one of many whose works were deemed degenerate, as they eschewed official socialist realist policy. He’d be lost to us, in terms of history, but for the efforts of his sister Yevdokiya Nikolayevna Glebova: “She stored the paintings in the Russian Museum’s archives and eventually donated them as a gift. Exhibitions of Filonov’s work were forbidden. In 1967, an exhibition of Filonov’s works in Novosibirsk was permitted. In 1988, his work was allowed in the Russian Museum. In 1989 and 1990, the first international exhibition of Filonov’s work was held in Paris.

During the period of half-legal status of Filonov’s works it was seemingly easy to steal them; however, there was a legend that Filonov’s ghost protected his art and anybody trying to steal his paintings or to smuggle them abroad would soon die, become paralyzed, or have a similar misfortune.”

It’s unsurprising that Filonov was deeply influence by fellow dissident Klebnikov: and his works – whether the obvious disdain present in this piece The Formula of Contemporary Pedagogy of IZO, or the more stark Those Who Have Nothing To Lose, or Animals, that would make a fine illustration for Orwell’s Animal Farm decades later – have an unflinching quality.

More of Filinov’s life and legacy can be learned here (and was the source cited for the biographical quotes about his life and work).

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Asya Kozina | Baroque Paper Wigs, 2016

October 14, 2022Asya Kozina | Baroque Paper Wigs, 2016

Historical wigs always fascinated me, especially the Baroque era. This is art for art’s sake aesthetics for aesthetics, no practical sense. But they are beautiful. I made a series of wigs. Paper helps to highlight in this case the main form and not be obsessed [with] unnecessary details.

There is something both decadent and timeless about Kozina’s work. The idea of a peformative lens comes into play – as these intricate, hand made (with no digital tools) ‘wigs’ only attain their ultimate beauty when worn by one of Kozina’s models, and the rest of the team comes together (meshing together, perhaps, like the paper in the artist’s constructions) to produce a moment that has as much to do with art historical tropes, as seen in the paintings of Jacques Louis David or Caravaggio, as it does with contemporary couture and fashion. The artifice of the apple, the pale face perfectly dotted with subtle spots of rouge, the winsome look eschewing eye contact in one scene and the feigned precociousness of the model looking directly at us in another all suggest this might be a Jean-Honoré Fragonard (more late Baroque, with a touch of the playfulness of Rococo) except for the stark palette, only broken by the red of the apple.

I think of Fragonard as the old Russian Imperial court often looked to France for its ideal, and there’s a sentiment of the elaborate, exotic Ancien Régime to Kozina’s many works: another act of imitation from an artifice of pretension that was, of course, all about social class and cultural capital.

But Kozina does more than just mimic: several bodies of work – such as the more ballistic Baroque Punk or more erotic Eve – employ the history of fashion as a starting point for contemporary considerations and conversations.

More of her work can be seen on IG at @asya_kozina or at her site.

The photographer for this work is Anastasia Andreeva, with assistance from Dina Kharitonova. The makeup artists are Marina Sysolyatina and Svetlana Dedushkina.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

José Clemente Orozco | The Clowns of War Arguing in Hell, 1944

October 6, 2022José Clemente Orozco | The Clowns of War Arguing in Hell, 1944

Fresco, Palacio de Gobierno, Guadalajara (alternately known as Carnival of the Ideologies).

Do I look like the kind of clown that could start a movement? (from the film Joker, 2019)

And butchered, frantic gestures of the dead. (Siegfried Sassoon, 1886 – 1967)

This fresco, created only five years before the artist’s death, is a good example of how ‘Orozco’s late works were characterized by a deep sense of anguish and pessimism as the artist grew skeptical about the future of humanity in the wake of sweeping technological advancements.’ (from here) The facile art historical reading is that this work was Orozco’s reaction to WWII, but even a quick perusal of his impressive body of work, and the cultural and social milieu he existed within, will indicate that this is a more complex and personal artwork than that.

It is, bluntly, a horrifying piece, and intended to be so: painted in the final days of WW II, one might see this as the answer to that image of the conference at Yalta, with FDR, Churchill and Stalin, still pretending to be allies and not with their knives out to gluttonously divide the spoils of war.

Recently I was lucky enough to write about the work of Orozco’s colleague Rufino Tamayo, who eschewed the political discourse that this artist – and other contemporaries like Diego Rivera or David Alfaro Siqueiros – considered essential to Mexican art. Orozco is at the opposite end of this spectrum from Tamayo: in this regard, Octavio Paz [the internationally renowned essayist and poet] once remarked “Orozco never smiled in his life.” (from here) Perhaps that is because – as with this work – Orozco had little use for genteel diplomacy, and knew that once you saw horrors, it was a conscious act of morality to not look away….I am also researching the Russian – Canadian artist Paraskeva Clark, right now, and her aesthetic was to respond to, and reflect, the world she lived within. That is what Orozco is doing here.

But if I’m honest, the reason this older work holds my attention now and I want to share it here is because it seems that very little has changed, in our political discourse, and that we’re still – willingly or press-ganged – onto Das Narrenschiff [A Ship of Fools], a favourite theme of Hieronymous Bosch and so many others….

A quick perusal of the civic candidates standing for office in my space of Niagara only emphasizes this appropriate cynicism.

Much more about Orozco’s life and legacy can be seen here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

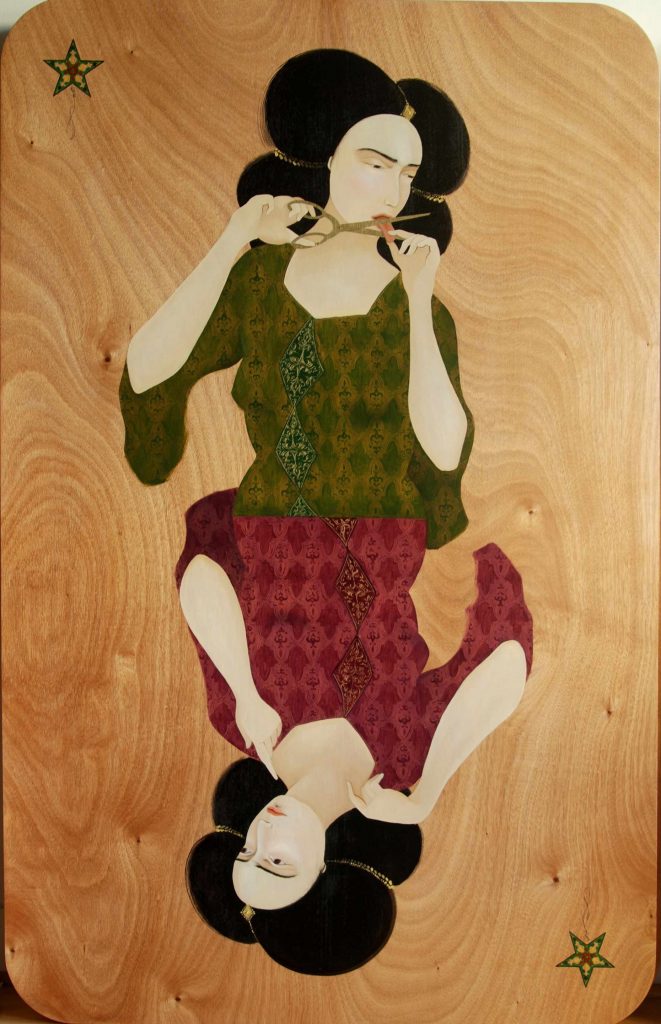

Hayv Kahraman | Migrant 3, 2009

September 29, 2022Hayv Kahraman | Migrant 3, 2009

Oil on panel 70 x 45 in. (177.8 x 114.3 cm.)

Hayv Kahraman was born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1981 but now lives and works in Los Angeles. She describes her work as being “a vocabulary of narrative, memory and dynamics of non-fixity found in diasporic cultures are the essence of her visual language and the product of her experience as an Iraqi refugee / come émigré. The body as object and subject have a central role in her painting practice as she compositely embodies the artist herself and a collective.”

This work was made around the same time as her series Marionettes which “explores this subject of female oppression with particular reference to war in the Middle East and specifically in her home land of Iraq. At the same time, she turns her attention to female subjugation found in the everyday, in a series of work focused on women and domestic life. Enslavement is depicted through strings controlling the movement of the women; they drift through the landscapes seemingly oblivious to, or accepting of, their fate.” (from a review in Contemporary Practices, 2010)

This image, as I was engaged in my frequent research about contemporary artists, caught my eye not just for its evocative if disturbing scene (that might be an act of self censorship, or a visual metaphor for a prohibition to speak or be heard), but also with what’s happening in Iran, right now. Feminism – that idea, affronting to so many, that people are all equal – is a contested narrative with overlapping and challenging voices, whether you’re listening to Hurston, Dworkin, Solanas, hooks, Simpson or Deer.

When geo politics enter the conversation – as with spaces where religion is a defining factor, such as the Middle East or the United States, lumbering like a rough beast towards not so much Jerusalem as Atwood’s Gilead – it only becomes more important to allow it to be defined personally, as, “the personal, as everyone’s so fucking fond of saying, is political.” (from the writings of Quellcrist Falconer, the founder of the Quellist movement, in Richard K. Morgan’s Altered Carbon)

As the work is titled Migrant 3, Kahraman might be ‘speaking’ of Iraq or of her new home, in the United States, just as the mirrored figures have differences, as time and experience takes upon any sense of self.

More of Hayv Kahraman’s work can be seen at both her IG and her site.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Julianna D’Intino | Connecting Rods: A Survey of Industry in the Niagara Region, 2015 – 2022

September 22, 2022Julianna D’Intino | Connecting Rods: A Survey of Industry in the Niagara Region, 2015 – 2022

To talk of the legacy of GM when you live in the city of St. Catharines is akin to how your tongue will always go to the gap in your teeth, seeking something that was there and now is not, leaving nothing behind but a perceptible absence you are unable to ignore.

Julianna D’Intino’s images, both moving and still – and I’ve been lucky enough to see several bodies of work she’s produced – often have a local focus, and in some ways she steps into that role of photographer as social historian. Often this involves her adjacent community in Niagara, exploring her own immediate heritage and circle. One such series can be seen here.

Connecting Rods: A Survey of Industry in the Niagara Region is a family story, as well as a local one. The ‘connection’ in the title of this series is not just a nod to an industrial interpretation, but also the families, communities and city that is part of a network that once had its epicenter in the abandoned wastelands D’Intino presents us with….and in her fine words about this series, D’Intino also draws connections to other areas with similar experience, such as with Atlas Steels or John Deere in Welland.

That potential for ‘nostalgia’ doesn’t mean what D’Intino is telling us is through rose – coloured glasses, nor does it gloss over the reality: her words about this work are as unflinching and honest – and engaging – as her photographs.

“This is but one personal case study in the myriad of lost industry of the Niagara Region. Would the return of the Niagara Region as a manufacturing hub provide a sustainable solution to the region’s economic woes? No, it would not. What is missing in the region is sufficient work at wages high enough to sustain a well-balanced life at the Niagara Region’s new inflated cost of living. The last time that such security was widespread was when manufacturing was a leading industry.”

The legacy of GM in St. Catharines is surely a contested narrative, with ground fertile for those from here – like D’Intino, or myself – to mine. It’s as rife as the industrial damage left behind at the site (an ongoing issue in civic politics here which has led to some grotesque and unsettling bedfellows), and there are differing opinions in play. Anna Szaflarski, for example, offers another perspective on this history here.

D’Intino’s site is here, and more images and D’Intino’s considered words about Connecting Rods can be found here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

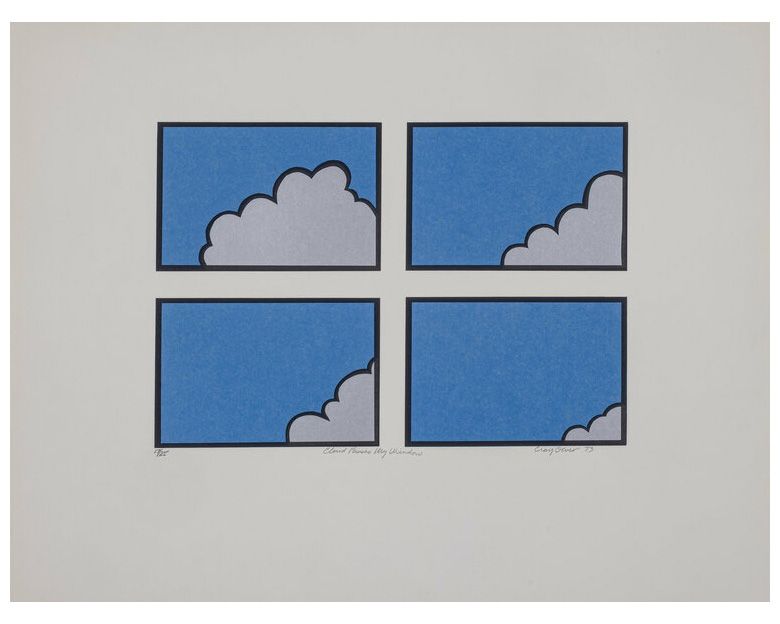

Craig Thomas Oliver | Cloud Passes My Window, 1973

September 15, 2022Craig Thomas Oliver | Cloud Passes My Window, 1973

Craig Thomas Oliver’s work always makes me melancholy. Perhaps it’s because not long after my return to Niagara I was approached to contribute an essay to an upcoming catalogue about the artist, published posthumously, as a means to bring attention to his art and accomplishments in Niagara. Later, I would include him in an exhibition I curated from the collection of Rodman Hall Art Centre, under the title of A Place To Stand, emphasizing artists in that archive who had built a place for others to grow and prosper within St. Catharines and Niagara. Both of those instances strike me as being about moments lost, or passing, with an implicit act of grieving.

Cloud Passes My Window is a small, delicate meditation, with clean, vibrant colours, like a sky so blue it might have been hammered into place. If you’ve visited Niagara Artists Centre (NAC) and their upstairs terrace – the CTO Terrace, named for Oliver, as a founding member of the artist run centre – this motif is familiar to you. On the left wall, a massive reproduction of Oliver’s simple and pristine white cloud on blue dominates the second storey space. It’s an amusing contrast, of the solidity of the architecture and the whimsical, ephemeral clouds, repeated like in this image: but in this work, it slowly leaves us, like any cloud – or person – who was here, and now gone.

I’ve spent many an evening there, with various NAC events, but I always think of it from a clear sunny afternoon, at the end of my first month upon returning to Niagara, in August of 2015. The CTO Terrace is a site often filled with music, so whenever I see any of Oliver’s ‘cloud’ works, Yoko Kanno’s song Blue comes to mind (Never seen a blue sky / Yeah I can feel it reaching out and moving closer

There’s something about blue / Asked myself what it’s all for / You know the funny thing about it / I couldn’t answer / No I couldn’t answer…)

Unsurprisingly, Kanno’s song may be about death, absence and loss, too. I’ve been told my mind goes to dark places, but that’s not entirely true, with the bright blue skies that Oliver shares with us, and that fills a wall in the loft space that bears his name, with ‘his’ sky to the side and the full sky above us…

But a more apropos element of textual ‘collage’ would be from Allen Ginsberg’s Elegy for Neal Cassady, written in the early morning hours (5 – 5:30 AM) upon learning of the passing of his friend and sometime lover:

aethereal Spirit

bright as moving air

blue as city dawn

happy as light released by the Day

over the city’s new buildings –

Lament in dawnlight’s not needed,

the world is released,

desire fulfilled, your history over,

story told, Karma resolved,

prayers completed

vision manifest, new consciousness fulfilled,

spirit returned in a circle,

world left standing empty, buses roaring through streets —

garbage scattered on pavements galore

Upon Oliver’s passing, NAC Director Stephen Remus offered the following tribute: “Craig was a key figure in the first wave of innovative collective projects that set the tone of wit and satire that has endured to define NAC today. [These include] the Niagara Now Billboard Exhibition (1972), Downtown Street Banner Project (1973), The Johnny Canuck Canadian Ego Exposition (1974), and The Johnny Canuck Canadian Ego Exhibitionist (1976). Craig was a master printmaker and he produced print work by many of his fellow NAC artists including John B. Boyle, Dennis Tourbin, Alice Crawley, and John Moffat.”

More about Oliver’s life and artwork can be read here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Don Bonham | Twentieth Century Technology Utilized by Third World Mentality, 1993

September 9, 2022Don Bonham | Twentieth Century Technology Utilized by Third World Mentality, 1993

Don Bonham (1940 – 2014) was a sculptor who produced monumental works that intersect with classical ideas about art and also incorporated contemporary references – especially as pertains to industry and technology. His work alternates between humour and a disturbing – yet attractive – aesthetic that reflects back on a larger society, especially in terms of how often any new technological advance is met with the brutal inquiry of whether “Can this make killing less of a hassle?” (Sadly, the second blunt question is, “Can I have sex with it?”). If you think I’m wrong, consider other works by Bonham that would please J.G. Ballard as three dimensional iterations of some of Phoebe Gloeckner‘s illustrations to his texts…or horrify him, edit as you will.

Don’t criticize Bonham’s presumed priapism and the implicit male gaze in his work: an era gets the artwork it merits. His industrial works often openly acknowledged and built upon the fetishization of object that was a continuation of a fetishization of the female body. His works are always seductive and well executed, if initially unsettling.

In his own words: “The gap between human and machine is constantly shrinking. Are we to become more like machines, or machines more like us? The creators of technology have imbued machines with human characteristics, and this tendency is creating a more hospitable environment for their acceptance by society. As an artist I am only enlarging upon this concept.”

Years ago, a fine film critic spoke of how futurism, in cinema, was either a clean, antiseptic space, like an Apple store, or more like Blade Runner, and broken, dirty and more part of an industrial gothic aesthetic. Bonham falls within the latter.

I have been accused of being somewhat ‘subjective’ as a reviewer, often relying upon ‘inappropriate’ sources and considerations when engaging with artwork. This bemuses me, and entertains me even more when I consider that a motivation for featuring a work by Bonham is the rather disrespectful – though typical of the vagaries of institutions that claim to protect and nurture culture – decision by McIntosh Gallery, at the University of Western, to de accession one of his works from their collection. Curator, writer and gallerist Terry Graff has been working against that, and you can see his efforts – and learn more about Bonham and his legacy – at Graff’s social media.

But in looking at Bonham’s sculpture here (and many of his similar works that meld, merge and mash up humanity and machine, with a sense of militarism that is almost inappropriately amusing and intersects with black humour) a Vietnam era anti – war anthem from the 1960s comes to mind. This is fitting, as Bonham came to Canada during the period when many men from the United States were fleeing their country, opposed to the war there. However, “Bonham enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and served in an elite Recon unit in Southeast Asia. After six and a half years, he was honorably discharged to enter the University of Oklahoma as an Art History Major. He left university before graduating and worked in Detroit on a Ford assembly line before moving, in 1968, to London, Ontario, where he discovered a dynamic arts community that reinforced his decision to pursue a career as a visual artist.” (from a retrospective of Bonham’s artwork at The Beaverbrook Art Gallery)

The song Sky Pilot by The Animals is as confrontational as Bonham’s Twentieth Century Technology Utilized by Third World Mentality, and for its time was surely controversial: and it’s necessary to include the print below that Bonham produced, of his modified – or realized – helicopters swooping down, mimicking that infamous scene where the ‘righteous’ decimate a village from Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Death rides a pale horse, a mechanized cyborg that’s surely a descendant of Albert Pinkham Ryder’s The Race Track (Death on a Pale Horse), coming down from the sky….

Regionalism has both defined – and deformed – Canadian art and Canadian art history (and is arguably why Bonham’s work is being so disrespected by the University of Western. Graff is more erudite and informed on this front than I). But regionalism is also the lens through which I respond to the terms of ‘First World’ or ‘Third World’ (cited in the title of this work) which seem as archaic at times as ‘Cold War’ (an epoch I had to explain to students, when I used to teach at a university, and let’s remember that the ‘Second World’ was the Communist Bloc, and the most avowed communist country now is definitely ‘open for business’…).

Bluntly, there are those who have and those who have not, and the tools at hand are used to enhance the former and demean the latter: it is the ‘order of things’, in the era of late capitalist modernism (to quote Jameson) or, as I like to call it, late modernist capitalism. Trinh T. Minh-ha (a Vietnamese – so she has an intimate understanding of the construction of history, as pertains to colonization / imperialism – filmmaker, writer, literary theorist, composer, and professor) famously wrote that “there is a third world in every first world, and vice-versa.” Bonham – and myself, initially – spoke of Vietnam. But you’re more likely to see a third world in your own city, overseen and monitored by a machine not unlike this sculpture (with the excessive militarization of police departments), in the skies over Detroit or Cleveland or Baltimore…or my own site of Niagara, or my previous space of Saskatoon, with tent cities and other ‘undesirables’, too often given harm over help, unlike other more harmful groups that squat, rife with sedition and fascist symbols….

Many thanks to Terry Graff for support, and conversations, that helped define this essay. Much more about Bonham’s life and artwork can be seen at Graff’s social media feed (there is also a petition to make Western reverse their decision here) and Bonham was a past Artist You Need To Know, in AIH Studios’ ongoing series. That can be enjoyed here.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Ema Shin | Hearts of Absent Women

August 26, 2022Ema Shin | Hearts of Absent Women

…as empty as an unremembered heart.

(Mervyn Peake, from his Gormenghast Trilogy)

I was born in Japan and grew up in a traditional Korean Family. My grandfather kept a treasured family tree book for 32 generations, but it only included male descendants’ names, not daughters. In my art, I have always tried to celebrate women and their historical handcrafts. These sculptural hearts are made from embroidery, handwoven tapestry, and papier mâché to recognize and celebrate the silent behind-the-scenes domestic duties of women and represent not only her emotions but serve as offerings or amulets for her protection.

(Ema Shin’s words, from here)

Of late, I’ve been watching the series Motherland: Fort Salem. I’ve a weakness – if you wish to put it that way, but I prefer affinity – for science fiction and fantasy (something I’ve been told, along with my interest in horror, is ‘inappropriate’ for an arts journalist…you know, like how the ‘only real art is painting’, ahem, to cite some of the karaoke modernists I endured on the prairies). The ‘alternate worlds’ are what interest me. When I was consuming William Gibson’s books, I was always more fascinated by the subtle things in his stories, presented as more factual and less chimeric (that the USSR eventually – for all intents and purposes – is run by the ‘criminal’ Kombinant, with the Russian mafia having fully taken over the government, that a religious cult appears that believes god speaks to them through movies – only from a certain era, of course – or that another character makes a living testing logos and brands, as she has an immediate, allergic reaction to any kind of advertising…)

In Motherland, a different world exists than that which we occupy: one where the Salem Accords have forged an uneasy alliance between the Witches of Salem and the United States Government, playing out in contemporary times. Imagine a military industrial complex based upon the magic of witches (or more accurately, the power of women), and – this is the part that is of more interest to me – a society that has formed around that, marking a genesis even before the United States became the United States, that is very matriarchal. Small things stood out to me, about how social ‘norms’ and customs play out very differently in this ‘world’ than in our own, especially around sexuality, power, who is expected to lead and who is expected to follow, and how history – in Salem – is overtly defined by a female gaze, if you will. I say ‘overtly’, as I always remember Martha Langford’s Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums, and those outside the frame who define it, but still are unseen metaphorically as well as literally…..

Ema Shin is a Melbourne based artist who was born and grew up in Niigata, Japan: she studied traditional and contemporary Japanese printmaking in Tokyo and completed a Master of Fine Art Degree in Nagoya. Shin has exhibited widely in Japan, Korea, Australia and elsewhere. Prior to this series, Shin focused on a variety of printmaking techniques and mediums, including Japanese woodblock printing, papier-mâché, embroidery, book making, Urauchi (chine-colle) and collage.

This interest in the physicality of materials continued when, due to motherhood and the pandemic, Shin “began to explore tapestry and embroidery…her red embroidered organs and [three dimensional] human hearts are beautiful to look at, and deeply personal-political in meaning.” (from here)

These are the archival giclée prints of the delicate objects Shin has created as part of her Hearts of Absent Women series (all photographs are by Matthew Stanton), and are an edition of 50.

From her site (which has many of her other fine works, so I encourage you to explore it): “Shin aims to create compositions that express sensitivity for tactile materials, the contemporary application of historical techniques, physical awareness, femininity and sexuality to celebrate women’s lives and bodies.”

Her Instagram is @ema.shin.

~ Bart Gazzola

Read More

Menashe Kadisman | Shalechet (Fallen Leaves), 1997 – 2001

August 19, 2022Menashe Kadishman | Shalechet (Fallen Leaves), 1997 – 2001

Installation, Jewish Museum, Berlin

When we were young, we wanted our art to change the world. But when Hitler bombed Guernica, did Picasso’s painting have any effect? I thought that maybe some things of mine could do good. My sculptures didn’t change the war in Lebanon. Maybe art is not about changing anything. It’s about telling you reality. (Menashe Kadishman)

I will admit that I rely upon the term ‘contested narratives’ a bit too much: but when confronted with Kadishman’s installation, where his own personal history (as the child of two committed Zionists, in the early twentieth century) and larger tropes intersect, contradict and in some ways twist and transform in a manner that is more apropos to a fictional story than our expectations of ‘reality’, I feel I have no recourse.

Kadishman’s installation is “primarily associated with the Shoah (the Holocaust) [but] it holds a universal message against violence and human suffering. Kadishman himself notes that the work can relate to different tragedies such as World War I and Hiroshima. In part, Shalechet derives its meaning from the context of its presentation. For example, it took on a new meaning in 2018, when it was exhibited at the Memorial Hall dedicated to the victims of the Nanjing massacre in China.” (I include a link as this horror is lesser known, in the cacophony of savagery that is human history, like the many – repetitive, interchangeable, eternal – ‘faces’ silently wailing on the floor of Shalechet, growing old and rusting and still unheard….)

Read more of Gazzola’s response to this work here.

Read More

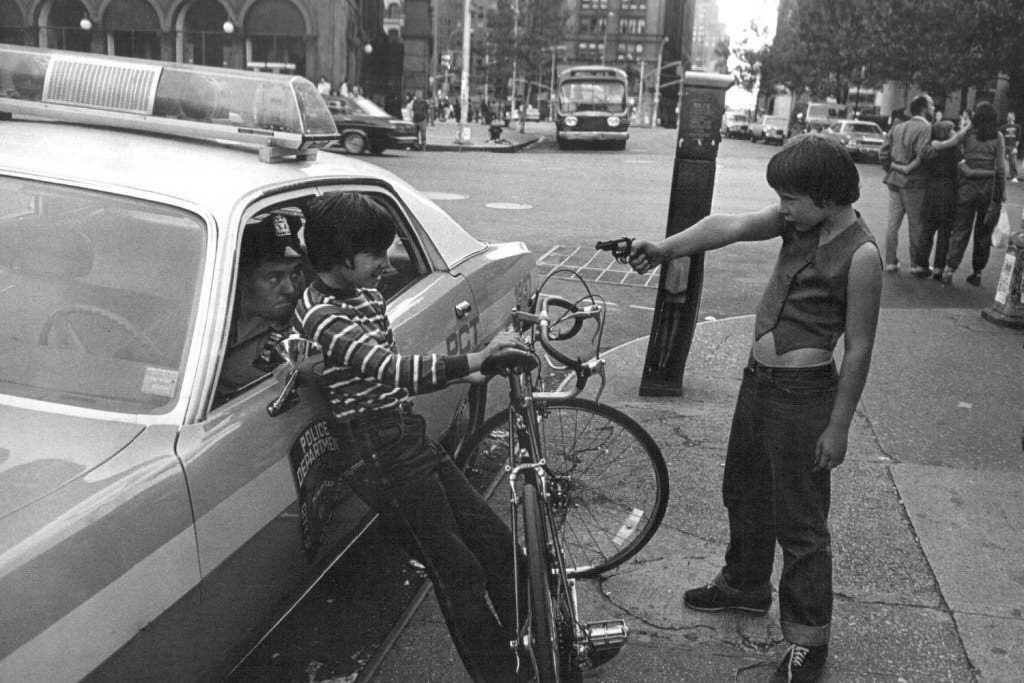

Gun Play | Jill Freedman

August 8, 2022Jill Freedman is a name you should know in the world of photography… but more than likely don’t. With a career that spanned 40 years, 7 (and counting) books and pieces acquired by major galleries, Freedman’s work connects deeply with her subjects in a manner unlike most documentary photographers.

From the very beginning, Jill was IN. She didn’t go to take photos of Resurrection City in Washington in 1968; she LIVED in the camp with the protesters for the duration of that campaign. She travelled with the circus for several months in the early 70’s to get her incredible photos of life under and around the big top. She embedded herself in the firehouses and police precincts of NYC and came out with work so beautiful and intimate that her two books on the subjects (Firehouse and Street Cops) were snapped up by first responders when they were re-released in the early 2000’s.

When Pulitzer Prize winner Studs Terkel wrote his oral history Working in 1974, Jill Freedman was who he interviewed when talking about photographers. From the first time I saw her work, I knew that there was an extreme tension in how she approached it. “Sometimes it’s hard to get started, ’cause I’m always aware of invading privacy. If there’s someone who doesn’t want me to take their picture, I don’t. When should you shoot and when shouldn’t you? I’ve gotten pictures of cops beating people. Now they didn’t want their pictures taken. (Laughs.) That’s a different thing.”[i] Freedman walked a very thin line between rooting for the underdog yet respecting authority.

You can find out more about Jill Freedman at http://www.jillfreedman.com/. Resurrection City, 1968 was recently re-published and can be found for purchase at your favorite bookstore or online. Firehouse and Street Cops are no longer in print, but used copies can be found online.

[i] Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do by Studs Terkel Text © 1972, 1974 by Studs Terkel – The New Press, New York, 2004, Pg. 153-154

~ Mark Walton

Read More

Recent Comments